In April 2014, just days after her partner, Årabrot vocalist and guitarist, Kjetil Nernes had been diagnosed with malignant throat cancer, Karin Park watched the band perform on stage at Bristol venue, The Church of St Thomas The Martyr.

Backed by an ornate reredos and flanked from above by two carved angel statues, Norway’s noise-rock band sounded as caustic and uncompromising as ever. But, unknown to the crowd, a vulnerability had crept in, masked by the gnarliness of the music, albeit just as threatening. For Park, the scene brought the reality of the situation into sharp, grave focus. “It was such a crazy picture to look at knowing that maybe he’s going to die, with those two angels looking at him,” she says today. “I get goose bumps when I talk about it.”

On that tour, all senses were heightened. Nernes had received the call from his doctor on the evening of the band’s departure to the UK for a short spate of shows, but, fearful it could be the last tour he would ever play, decided to forge ahead anyway. Naturally, Park had been “absolutely horrified” by the news, but had accepted his decision. “If I had talked him into getting the treatment straight away and then if he could never sing again, he would have probably blamed me forever for not letting him do that last tour,” she reasons. “But it’s awful when you know the cancer gets worse day by day and you deliberately don’t do anything about it.”

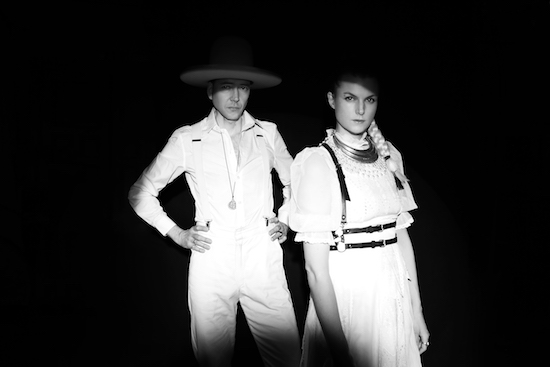

After undergoing intense treatment, Nernes is now cancer free, but his brush with death altered Årabrot forever. Up until that point, although Park had contributed piano to the band’s recordings on their self-titled album in 2013, expanding to pump organ, synths and occasional vocals on subsequent releases, her role had been confined exclusively to the studio. Having had her own successful pop career since she was 17 – the now 42-year old Swede is a household name in her home country – it was an arrangement that suited her. But following Nernes’ diagnosis, she craved more involvement with Årabrot, becoming an official, touring member after the band’s 2016 record, The Gospel. Last year, as they started work on new album, Norwegian Gothic, Nernes and Park decided they were going to front the band together. “I’ve realised that actually we need each other,” she says. “We need to be on stage together and do this thing together.”

That shift, she explains, has come gradually, the result of the couple’s musical preferences coalescing over many years. “Now, when we’ve listened to so much music together, we can think along the same lines and we can reference a song here and there,” she says. “He doesn’t have to direct me in the same way he had to at the beginning. Kjetil makes the demos and then he plays them to me, quite undeveloped and rough. It’s almost like he delivers a bud of a flower and I make it bloom.”

Norwegian Gothic, the band’s ninth album is as dynamic and unpredictable as ever, stuffed with squalling sex and death anthems that could career off the rails at any moment. Like every Årabrot album, Nernes has roped in a revolving cast of musicians, this time including Lars Horntveth (Jaga Jazzist), cellist Jo Quail, Tomas Järmyr (Motorpsycho), Anders Møller (Turbonegro, Ulver) and Massimo Pupillo (Zu), but Park’s influence slices through the noise. Squeezed in amongst the nods to punk, black and industrial metal, anthemic choruses push Årabrot’s sound into new dimensions on ‘Kinks Of The Heart’ and ‘The Lie’, in the snakelike grooves and synths of ‘The Rule Of Silence’. It’s like sherbet for Swans fans. “I think it’s a lot more influenced by my electronic side and it’s a lot more melodic,” says Park, explaining that, over time, the duo have become more in tune with what each other want out of the music. “I was actually the one to point out to Kjetil that he could sing. He had never even tried to sing, sing. He’d just been screaming before that.”

Årabrot finished recording Norwegian Gothic before the spread of Coronavirus caused Norway to lock down in March 2020. Later that same month, Park released her sixth solo album, Church Of Imagination. Seeing the two albums side by side is still a source of disconcertment for her. “I never thought I would join a band, not in a million years,” she says, I’m such a solo player, I always have been, so I’m surprised that I feel comfortable. But it’s also a cool thing because we can sometimes get lost as women. We need to be so independent, our time is all about that now. If you can team up with someone on your terms, or find some terms together, that work, that collaboration is the most amazing thing.”

Does this mean her solo career is now on the back burner? “I need to do both for me to feel complete in my artistry,” she replies firmly. “Being in Årabrot works because I have also my own project. If I stopped doing my own thing, I would be a lot less cooperative in Årabrot because I’d want things my way. That’s not something I’d give up ever.”

Spoken like someone who knew what she wanted from life from the very beginning, Park’s Instagram bio reads, “I do exactly what I want whenever I want to do it”. She grew up in Djura, a remote village in central Sweden, with about 400 inhabitants where red wooden, white roofed houses pepper a sparse landscape and the nearest shop was 5km away. Her childhood was happy, but from a young age, she yearned for something more. Born to religious parents and one of four siblings, she found her calling when she was just two years old – singing in the choir at the church which she attended with her family. “My first meeting with music was me singing. I was singing and making music before I’d even heard a record.”

When she was seven, her family moved to Japan, where she attended missionary school. Having experienced her first taste of a huge city and a new culture, when the family moved back a few years later, Park struggled to readjust. “I was totally single- minded,” she explains with a shrug. “I wanted to do music and no one else did music here. Also, when we came back from Japan, I had lived a different life from everyone else for three years and there were so many things that happened that they didn’t even believe were true when I told them. I felt I couldn’t relate to any of my school mates, I just knew they wouldn’t have anything to do with my future life.”

She sought escape and as a young teen, was accepted to study at Stockholm’s Music Conservatory. Initially though, her mother forbade her to go, concerned, not without good reason, that she was too young to leave the family home and move three hours south to the capital. In response, Park accepted her place at the school behind her parents’ backs and set about renting her own apartment with state-funded support. She was just 15 years old. “It was a bit early, it was a bit silly and it was quite tough in the beginning,” she admits, remembering her mother’s tears as she left her in Stockholm for the first time. “I have to say. I don’t know if I’d let my own daughter leave that early, but it was all I wanted. I was very driven. I think that’s why they let me do it in the end.”

After her studies, during which she briefly shared a classroom with Robyn, she moved to Norway where her career took off, signing a major record deal with Universal Records. Her folk-pop solo debut, Superworldunknown, was released in 2003, winning her a Norwegian Grammy in 2004 for Newcomer Of The Year. A dream come true surely? “I was on the front page of the culture part of the newspaper and I was waving at the audience as I walked down to get my award but I was furious in that moment,” she remembers. “I hated my label. I didn’t know that, as a young artist, when you sign to a major label you sign away a lot of your rights. I got a big fat advance and they released the video [for single ‘Superworldunknown’] without me even approving it, there were so many things they didn’t…” she pauses. “They pissed on my integrity basically.” The passing of time has offered a new perspective. “I actually called them years later and told them I knew they did all they could,” she adds. “I wanted to apologise for being a cunt because I was really a cunt to them. They tried to pave the way for me and make me hugely successful and I really had my claws out.”

By her third solo record, 2009’s Ashes To Gold, Park was disillusioned. Having spent six years swept up in the music industry machine, she realised she had zero passion for the music she was making. Longing to make more physical record that reflected her love for Depeche Mode, Kraftwerk and Front 242, she flipped the table. Researching how to work with analogue synths, she drew inspiration from architecture and chopped her hair into a sharp bob to reflect the “strong shapes” she was creating in the music. By her fourth record, 2012’s glacial, Bjork-meets-The Knife-inspired, Highwire Poetry, she had transitioned completely into a moody electro-pop maven and had headed out on tour with SBTRKT and Azari & III.

“When I discovered synthesisers, that’s when I made a more conscious choice about what kind of artist I actually wanted to be and what kind of sound I wanted to have,” she says. “In the first five years of my career, I was just me, you know? But I realised I wanted to communicate to an audience that were interested in the same things as I was. I wasn’t interested in the things people would ask me as an artist anymore.”

2009 was an important year for Park. As well as making her break towards musical independence, it was also the year she was introduced to Nernes on a “crazy night” in Bergen. And for now, that’s all the detail we’re getting. “We will write the true story in the Årabrot biography but I’m not sure if the world is ready for it yet,” she jokes. “It wasn’t very romantic but it was Årabrot style for sure.” Whatever happened though, it sparked a whirlwind romance. “I fell so instantly in love with him,” she says. “I had a few different people I was dating at the time and the day after I met Kjetil I called them up I said, “Look I don’t ever want to see you again I’ve met the man of my life.” Kjetil wasn’t aware of this at all and I didn’t see him for a long time before I realised, I can’t live without him. I think we moved in together after three months.”

Prior to Nernes’ cancer diagnosis, he and Park relocated from Oslo to Djura, back to the remote Swedish village where she had grown up. A strange decision given her desperation to leave as a teenager? The move, she explains, was nothing to do with recapturing or revisiting anything from her youth, more about creating a “new reality for herself”, as well as others who might feel trapped. “When I moved back, I wanted to create an opportunity for people who live here now,” she says. “To make people feel there is someone who does crazy things in this village, maybe there’s a little bit of hope.”

The couple bought the church that Park attended with her family as a child, setting up a rehearsal space and studio where they’ve recorded every album since 2016’s The Gospel. When they moved in, the place was like a time warp. “There were little sugar cubes from 1986, potato mash powder from the 80s. Everything was from the 80s,” she says. “There was a Bible that was 300 years old.” Since then though, they’ve changed some things. Neither Park or Nernes are religious – “I would say I’m a spiritual person but I’m not a specific religion,” Park clarifies – and not long after moving in, they had the church deconsecrated – “Only one person in Sweden can do it. He came and we had a ceremony where we took down the cross and walked, in a line, over to another church and placed the cross in that church.”

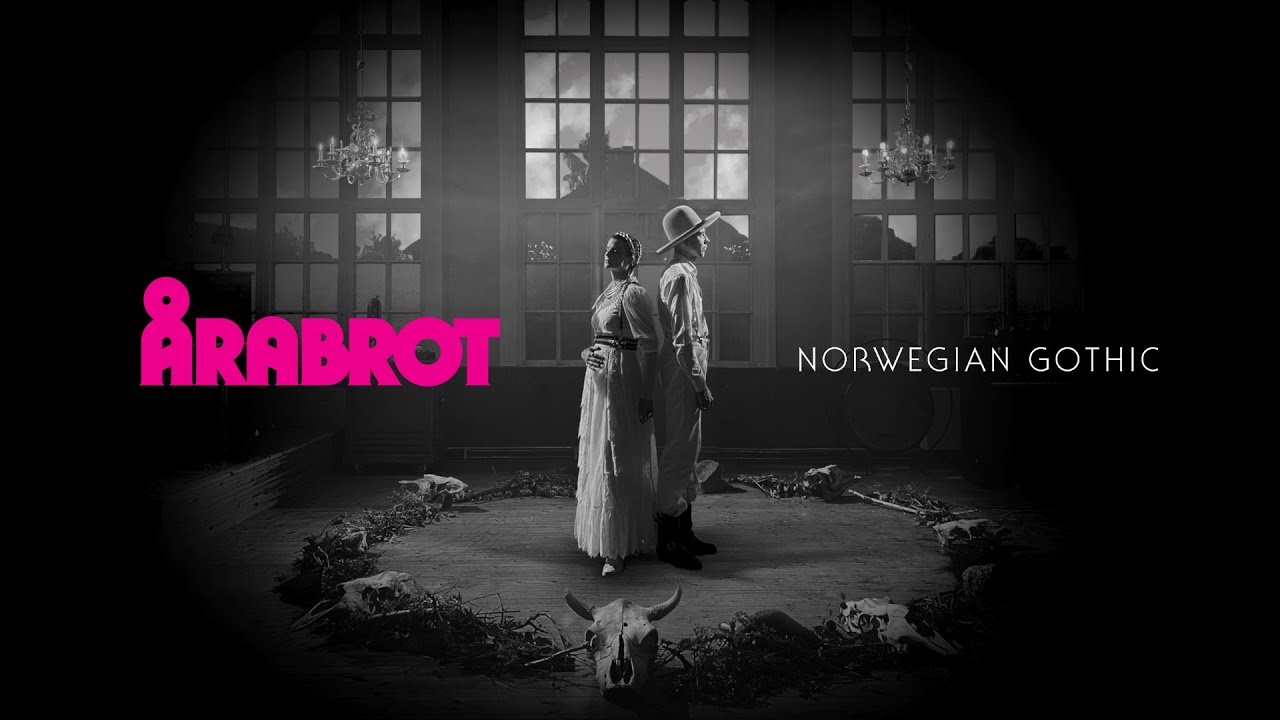

Meanwhile, they’ve redecorated – “It looks a lot more Årabrot-ish now” – although the church hall looks exactly as Park remembers it as child: a beautiful room, lined with three, arched floor to ceiling windows and lit by chandeliers hanging from thin, delicate chains.

Now, it’s Årabrot’s heart and hub, the place they record and practice and the home they share together with their two young daughters. In 2015, the couple were married in a candlelit ceremony in the church hall. Norwegian Gothic’s cover art was shot in the room last year, at 3am on the morning of Summer Solstice, while the church was also the location for the music videos for recent singles, ‘Kinks Of The Heart’ and ‘Hailstones For Rain/ The Moon Is Dead’. “I think people think we’re pretty weird,” says Park of her neighbours when asked if she and Nernes are seen as the eccentric couple who live in the village church. “But we tend to involve them in our crazy projects so they’re in on it.”

There’s a moment towards the end of the band’s 2016 documentary, Cocks & Crosses, where Park reveals the existence of Nernes’ 20-year Årabrot plan, admitting that she has no idea what it is. Today, she jokes that he has already written the next two records (“I can’t keep up with him”), yet there’s a sense with Norwegian Gothic that she’s now a firm part of that plan. “We very much share the vision for the two of us, our family and for Årabrot as a band,” she asserts. “And it’s fun to make those plans.” It was her who first suggested to Nernes that the band would be perfectly suited to support noise-mongers Boris on tour. “At the time that seemed impossible, but then three years later they asked us if we wanted to come as their special guests.” She also argued that Årabrot’s newer material would be suited for radio play – a concept Nernes has shunned for 20 years. For the longest time, Årabrot has been his baby, his singular vision but now Park’s sonic and visual contributions are propelling the band down previously unseen paths. “With my music taste I’ve opened Kjetil up to new possibilities,” she says. “We’ve both become a lot more open minded to what we want to do and also to dare to have grander plans. We want to move big mountains.”