Cathal Coughlan by Gregory Dunn

“I’m kind of Mr. Tin Pan Alley really, even if what I’m doing is supposed to sound like Henry Cow meets Ligeti or something, I’m still verse-chorus-verse-chorus in my fucking head, you know?”

It’s been over ten years since the Cork-born former Microdisney and Fatima Mansions frontman delivered a solo album (the last being 2010’s Rancho Tetrahedron), and you’ll see it being hailed in some quarters as the proverbial return to form. In fact, after the sonically patchy and patchwork-like Grand Necropolitan – which nevertheless features some obscure gems and the hugely affecting ‘Unbroken Ones’ – Coughlan’s releases, from 2000’s Black River Falls onwards, have documented his flowering as one of the finest living practitioners of what he calls the “North European ballad”.

The oft-cited influence of Scott Walker is only one strand in records that have seen elements from European musical theatre, avant-garde classical, Nino Rota, Rock In Opposition-style prog, folk and experimental electronics corralled into ambitious, twisting song-structures and arrangements (peaking in complexity with the fragmented narrative of 2006’s Foburg, recorded with the Grand Necropolitan Sextet and derived from the Flannery’s Mounted Head stage show).

This can sometimes make for a forbidding musical environment, matched by a searingly articulated despair at the pass that neoliberalism, Big Tech, imperial nostalgia and the deliberate stoking of ideological confusion have brought us to. It’s a world populated by white and blue-collar criminals, misfits, exiles, drunken hangmen, corrupt politicians, deluded denizens of the virtual sphere, past-their-prime pop stars and thwarted romantics; global and personal disaster are hopelessly intertwined. This is always leavened, though, by that sonorous voice, both exultant and wounded, Coughlan’s absurdist humour (one which, in its most extreme form, has manifested in perverse comedy projects like Bubonique), gift for satire and an ability to stop you in your tracks with a brilliant turn of musical and lyrical phrase.

His songs can give rise to some most unusual earworms – “ask about the Hounslow wall of sound” from ‘Best Say We’re Not Serious’ on Rancho Tetrahedron still comes to me unbidden with startling frequency.

What the new album, Song Of Co-Aklan, does do, without dumbing down in any conceivable way, is present his songs in a punchier, more immediate manner than they have been for quite a while; the double bass has been substituted for an electric one.

It’s also the most open to Coughlan’s musical past, both in terms of the personnel – Grand Necropolitan Sextet members join Sean O’Hagan, his founding partner in Microdisney; Luke Haines, with whom Coughlan worked on The North Sea Scrolls; and The Fatima Mansions’ Aindrías ‘Grimmo’ Ó’Grúama (aka Sister Mary Aindrias O’Gruama, Princess of Palestrina, Daughter of Pope Urban X among other aliases) – and the songs; ‘St. Wellbeing Axe’, featuring Ó’Grúama, bristles with the heretic preacher energy of the Mansions at their best while ‘Falling Out North St.’ has the nostalgic tug of Microdisney’s ‘464’.

Along with the recent Microdisney The Clock Comes Down The Stairs reunion shows (and if you want to read more specifically on that album, you can do so here), this would be reason enough to take stock of a catalogue that can be as confounding as it is rewarding. But 2021 also appears to mark a fresh phase in Coughlan’s career; it sounds as though the ‘Co-Aklan’ persona will be further fleshed out; there’s a collaborative project called Bring Your Own Hammer, (“centred around crimes of violence that may or may not have been committed by people who are Irish or of Irish origin throughout the world in the 19th Century. Trips off the tongue!”) and talk of less structured, noise-based work.

And then there’s the imminent first release from Telefís, a collaboration with Irish superstar producer Jacknife Lee. The latter’s credits include R.E.M., One Direction and Taylor Swift – and Coughlan seems rather tickled by the suggestion that he could now be considered a ‘topliner’. It will surprise some, but close observers will have long suspected that he had this kind of weirdly catchy electronic pop project in him too.

Microdisney – ‘Sun’ [Peel Session] (1983)

Cathal Coughlan: That was from the first session we did, right after it was written. One of the things about it is that I didn’t know that referring to a woman as a dog was an actual thing. I just thought introducing anthropomorphism into a song was quite a funny thing to do. And there’s this kind of drunken tirade thing about it. It isn’t like it’s misogynistic, it’s about being penniless in your late teens when other kids have money and are going out and having a having a good time. But of course, what you don’t realise then is that those may be the salad days of those people’s lives and you shouldn’t be fucking sneering at them. Just because people are engaging in escapism doesn’t mean that that’s all there is to that person. There weren’t many Microdisney songs we played on the reunion shows that caused me any concern, but that was definitely one. But it does encapsulate a viewpoint, and melodically and in every other way I enjoyed singing it again.

Microdisney – ‘Town To Town’ from Crooked Mile (1987)

CC: It was inspired by Nic Roeg’s Insignificance and a banned TV documentary that was released belatedly then about what the years after nuclear annihilation would be like. It might have been Threads. The idea from the Roeg movie was that so many of our vanities are rendered irrelevant by circumstance. The particular totem for my generation was nuclear war and, of course, that hasn’t gone anywhere. But we now have some other ones on top which are far more pertinent, and it just goes to show how banal catastrophe can be. We could have played to our strengths a bit better than we did but ‘Town To Town’ was a successful moment in all of that. Lenny Kaye got a great performance out of the rhythm section and we achieved the kind of panoramic thing that was already there in the chord structure. I learned so much from working with Lenny, it was just incalculable really. It was the beginning of me becoming much more of a singer than an aspiring singer.

The Fatima Mansions – ‘Blues For Ceausescu’ (1990)

CC: I had a really primitive synth demo of it, if you can imagine that. Up to that point, my song structures were sacrosanct in a way. And I thought everybody can play better than that, so we did this and, over the course of two weeks, it turned into a monolith which we pumped up more in the studio and subsequently as well. ‘Ceausescu’ was about full tilt the whole way, going up a bit further and then just coming back to full tilt again. You could call it self-indulgent, certainly. But it felt great most of the time.

Can you put yourself back into your mindset at the time?

CC: Pretty much an outlaw mentality. The experience of having been in a band that was doing okay and tumbling out of it was pretty unsettling and I was existing on a hovercraft of alcohol and caffeine. When the poll tax came along, any pretence of being able to be off the grid and get by somehow really felt like it was under direct assault. Obviously, a lot of Viva Dead Ponies is like that but ‘Ceausescu’ was a full frontal, ‘Let’s do this’ kind of exhortation. It’s like, you over there in Downing Street or Whitehall, do you see what happened in the Eastern Bloc? We know you don’t like it, because we know you wanted it as a bogeyman. Your excuse is gone now, what are you gonna do? So it was a big, big taunt.

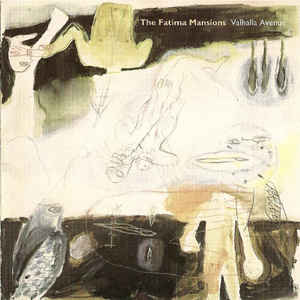

The Fatima Mansions – ‘Valhalla Avenue’ from Valhalla Avenue (1992)

CC: The album was a spectrum from The Young Gods through Belgian New beat, Belgian industrial, Chicago industrial, the whole Ministry, Revolting Cocks school of thought. And anything from my past that seemed to kind of inform that so Wire, who I’ve always admired massively. And Irish traditional music, that would be almost like a sounding board. It’s funny that it’s taken a whole generation to see it evolve, but the kind of song that was in my head then was what Lankum, Ye Vagabonds, Landless and Lisa O’Neill are doing now. Artistically it was very satisfying to do because it really encapsulated the way that I thought we were going to be able to do things, which was to take snapshots every couple of months and make an album out of that. But it transpired that there really was no part of the music industry that was willing to cope with that from anybody who wasn’t a big success.

The Fatima Mansions – ‘Everything I Do (I Do It For You)’ from Ruby Trax – The NME’s Roaring Forty (1992)

CC: Me and Paul Jarvis had been doing the Bubonique stuff. I knew Paul because Slab used to rehearse in the room next to the Mansions. We put out the ‘Screw’ single which was Steely Dan meets Swans! That was the brief on that. When that NME number ones thing came up, it seemed like the best way to do a really detailed takedown of a song. I really wanted to do ‘I’ve Never Been To Me’ but it turned out that only went to number two or something. I’d always thought of Bryan Adams as a pretty good egg really, for somebody in his position. But I detested the song. We had a percussionist called Bruce Arthur, he was a Newcastle friend of Nick our keyboard player. But he was a phenomenal musician, he played for Pierre Boulez, everything. There was a really great trumpet player, but otherwise it was just squeezy toys and, you know, porn samples. But I should say there was no porn in the studio, it was just stuff that had been stockpiled previously. That was a double A-side [with Manic Street Preachers’ ‘Theme From MAS*H’] but treated as something else. On Top Of The Pops, they wouldn’t put our whole name into the on-screen graphic. It was like, it’s Manic Street Preachers and Fatima M!

Cathal Coughlan – ‘Officer Material’ from Black River Falls (2000)

CC: I wanted to do something that was focused and confected when I could finally make an album for Cooking Vinyl. ‘Officer Material’ went through a few evolutions, but my friend Renaud-Gabriel Pion was up for doing string arranging, woodwind and all that so I thought, yeah, let’s go the whole way.

On a recent programme about Bowie, someone was saying that the thing he was most proud of was his chord changes, and I wonder whether you feel the same about yours?

CC: Yeah, quietly. Well, it can be a bit of a handicap. Sometimes if you’ve sweated too long over something so that it tweaks your ears when you’re just playing it on the piano, it can appear arrogant to dish something like that up. I’ve had people who don’t know me very well who’ve played with me on one-off projects, and one person who I have a lot of respect for turned to me and said, “How did you write this?” But it wasn’t so much, ‘You’re a genius, I think it’s incredible’ as ‘Christ almighty, what was the thought process?’

The North Sea Scrolls – ‘Witches In The Water’ from The North Sea Scrolls (2012)

CC: It was a terrific experience and it enabled me to focus, funnily enough, really deeply on the songs I was writing for it. But between us, we kind of evolved these scenarios that one or other of us would run with. And then Andrew [Mueller] would write a narration – or sometimes concurrently. We were doing it for a very small show in Edinburgh, where some of the material caused the audience to blanche because you could hear every word. Luke [Haines] was really getting into a stride of making albums without a band. So on his tracks, he laid down a great template for arranging. I’d been a fan of his stuff anyway for quite a while at that point, but – and this is the only time it’s happened to me – you can’t beat the kind of inspiring effect of having something like ‘I’m Falcononetti’, his track, that is just so contrary in its scenario, you know?

François Ribac & Eva Schwabe feat. Cathal Coughlan, Dave Gregory, Gilles Laval, Philippe Istria – ‘To The Fade’ from Into The Green (2017)

CC: It reminds me of this sense of community that there has been on the shows that I’ve done in France. Francois and Eva both have that background from way back, doing this Europe-wide music theatre festival that used to happen every year and also working in the public system in France. When they sent me the invitation for Qui Est Fou? [the first show Coughlan did in France] it was a bit like the Brecht thing later on – I thought, ‘I can’t not do this.’ It’s in the vein of things I’ve been wanting to do since I was a teenager. And it expanded my palate and made me focus on my voice, because my principal function was to just be able to fucking well sing when you turn up

How important has the influence of Brechtian musical theatre been on your work?

Doing the Change The World Brecht show in Dublin made me delve into the life. As I’m sure you know, the life is checkered but there is nonetheless a real bravery about the way that he conceived the work, despite Elizabeth Hauptmann and others not necessarily having their roles properly acknowledged in his lifetime. It made me rethink the way that I’ve been hearing a lot of the songs. It’s something that I really look up to, so participating in the show was really terrific, for me to feel that I could ride the actual dragon, singing the ‘Song Of Mother Courage’ with a really crack band. And being on the same stage as Ute Lemper and Blixa [Bargeld], it was just fucking beyond my wildest dreams really.

Side 4 Collective – ‘Numb’ from We Burn Bright (2020)

CC: A chap called Dave Hingerty, who in one part of his life is a drummer in Dublin, way before any kind of lockdown or anything like that, had the idea of doing a whole lot of drum tracks and just inviting people to collaborate digitally. And there was one track on there, where this other Dublin musician known as ROMY had put some sections on it. I thought, ‘God, this is really good.’ I asked, ‘Can I just piggyback on this?’ So across the generations and the oft-derided technological space, these synchronicities can happen. And if I have seemed to pile absolute opprobrium on that it isn’t my intention, because even when I was turning on my little transistor and trying to pick up Radio Caroline and John Peel after dark, in East Cork, in 1970 and 71 probably, this was the kind of synchronicity that I had in mind, the fact that you could hear Lebanese music [and think] ‘What the hell is this? And why does it keep cutting out in favour of this oscillating sound that the upper atmosphere is just generating by being bright or dark?’

Cathal Coughlan – Song Of Co-Aklan’ from Song Of Co-Aklan (2021)

How much of the new album was in place this time last year?

CC: A fortuitous amount was. We’d been recording Nick Allum’s drums and acoustic piano at Snorkel Studios. There was still a lot left to do but it wasn’t insurmountable. People really showed up for me and recorded themselves, and I did quite a lot at home.

I think some of it is just the business of getting older, and some of it is just the kind of situations you find yourself in, but the prevailing feeling I’ve had about music making over the last few years is the community aspect of it. The sometimes-acidic nature of my output can make me seem like quite an isolationist as a human being, and I wanted to dispel that to some extent. And the other thing was wanting to restart the engines for real, and I think a good way to do that is to think, well, I’m not going to pooh-pooh ideas as they come along. As you know I’ve always been a bit of a gadfly in terms of the things that interest me musically. And so, on the album I wanted to do something that at least aims for the kind of poignancy of a lot of northern soul records that I love. And the industrial thing, it was like, ‘Well, I know how to do this.’