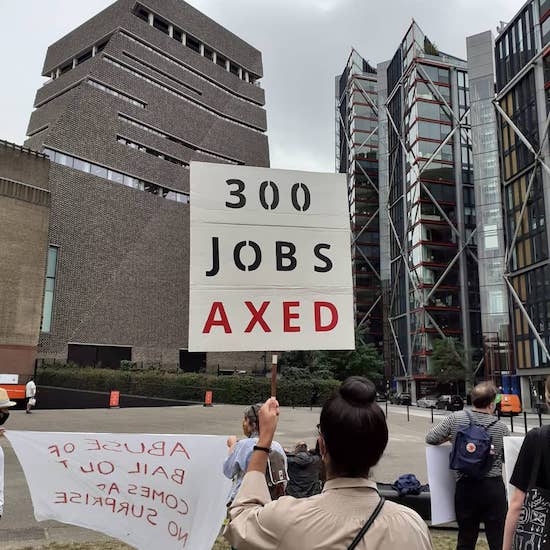

Photo by Jaime Rory Lucy © PCS Tate United Branch

Across Europe, arts workers are bringing attention to the inequalities within their industry. Part of the reason for the boom of activity stems from the fact that too many workers, often those most in contact with the general public, were made redundant at the start of the crisis. Lockdowns have also provided an opportunity to take stock, discuss, and organise. In London in August 2020, Tate United, a group of PCS Union members working at the Tate Britain and Modern’s shops, went on strike. This was to protest Tate Enterprises’s plan to make 313 people redundant despite receiving £7 million in state support. As TU’s site explains, these redundancies were going to account for “about half the staff from some of Tate’s most diverse and lowest-paid teams.”

DISCE’s Creative Workforce In Europe Statistics Report from 2020 describes how the 1990 Broadcasting Act deregulated and individualised the UK’s television sector. This provided the blueprint for related neoliberal reforms that would spread throughout the “culture economy”, whose components and actors differ depending on who’s conducting the research (for example, while UK born statistics may well include workers such as cleaners, Eurostat numbers won’t).

Following the Thatcherite economic zeitgeist, New Labour was a harbinger of many of the reforms whose effects are being felt today. Their Department of Culture, Media and Sport described the creative industry as that which galvanises individuals to create “intellectual property.” Tellingly, there’s no mention of collective work or collaboration or common ownership. In essence, the creative industry is just another brand for capital gains through landlordism.

The introduction of gig economy logic into this heavily individualised system – in which people are increasingly encouraged to consider themselves freelancers rather than employees, competitive armies of one rather than collaborators – is a divide and conquer tactic, and has resulted in workers at arts institutions keenly experiencing economic precarity, especially during the pandemic. It’s perhaps unsurprising that it’s been so easy for the arts industry to implement individualisation seeing as we still too often fall for the myth of the individual genius that surrounds much of art discourse. Meanwhile, those at the bottom of art’s feudal pyramid are increasingly placed on zero hour contracts, or aren’t paid at all. Unpaid internships have become the norm for a variety and large number of institutions.

© PCS Tate United Branch

As DISCE’s Report (composed of research conducted before the pandemic) states, the neoliberalisation of the arts “has had a negative impact on diversity figures amongst its workforce within the UK, with certain groups, for example women, being more subject to workforce precarity.” Additionally, in “the Creative Industries, Digital and Telecoms sectors, fewer than 10% of jobs were held by those considered ‘less advantaged’, compared to the UK average of (32.3%).”

Outsourcing has become another cause for concern. The End Outsourcing campaign by students and staff at the University of the Arts London describes outsourcing as a practice that creates a “two-tier workforce” whereby those directly employed by an institution receive all the benefits of labour law while outsourced staff are often left without maternity and paternity leave, sick pay, and other necessities. This exploitative scenario is especially harsh to frontline workers such as cleaners and security. Campaigns are also taking place in protest to similar practices by Goldsmiths College and the Imperial War Museum.

The UK isn’t the only site of such problematic developments. In Barcelona, around the same time as Tate United were taking action, SUT Union members working at various city monuments such as the Sagarada Familia went on strike. According to literature handed out by those on the picket, this was in reaction to MagmaCultura (a company that manages many such tourist attractions and which claims to “work for the culture”) taking away paid holiday days, underpaying staff, and constantly modifying schedules. All this despite the fact that in 2019 the Familia made €100 million in profit from entrance fees alone.

Some arts workers aren’t part of traditional or long term union structures, or are unsatisfied with the way in which traditional unions function, and so are starting from the ground up. Cultural Workers Unite was formed in Rotterdam by artists and others to draw attention to the situation suffered by “un-contracted, freelance and precarious workers”. In an industry that encourages the hustler mentality, CWU say they aim to “nurture solidarity and support each other now and beyond this time of crisis.” Another mission of theirs is to de-centre the importance of institutions, thinking more about community-embedded cultural practices. In collaboration with numerous other cultural and activist organisations, their most recent action has been to squat a former community centre, purposefully left vacant for a number of years by a housing corporation, in Rotterdam West. This has drawn attention to the importance of space in regards to autonomous community formation and also the decreasing quality and availability of affordable housing.

Traditional union organising has benefited those at the Tate’s institutions. After forty-two days of action, in November 2020 Tate Enterprises agreed to negotiate an improved re-employment and re-deployment policy, give staff made redundant preferential recruitment options for vacancies, and increase redundancy payments. At the time of writing, those voluntary redundancy consultations are coming to a close. Since then, thanks to more recent negotiations regarding those working in the Tate galleries around 150 gallery staff will soon be leaving with improved voluntary exit terms. Tate’s PCS members are also part of the Art Workers Forum, self described as "a group of rank and file reps from various unions working within art institutions, including galleries, museums and universities." Through the Forum, reps can support each others’ disputes, pickets, protests and other social movements. The Forum is attempting to cultivate responsive organising and avoid overly procedural and bureaucratic hierarchical structures.

Creative and engaging propaganda is a recurring component of many of these movements. Tate United produced a pamphlet titled Artists Are Workers, Workers Are Artists, that platformed work produced by some of those on strike as well as the practicalities behind making art itself. CWU have made a mini-zine which features “questions for/from cultural workers” that help readers interrogate the nature of the institutions they either work for or visit. The “what art should be like” question has also been asked by CWU. In discussions about what form public art should take, they’ve argued for the importance of impermanent work that does not centre an individual.

More recently, Art Workers Italia launched HYPERUNIONISATION, an “online platform aiming to foster a transnational network of groups, institutions and organisations focused on the rights of cultural workers in Europe and worldwide.” To launch the project, AWI managed to gain support from the European Cultural Foundation. As well as building networks between workers, they’ve also hosted roundtables discussing strikes, gaining leverage, and getting paid with reps from worker-led organisations from within and outside the European Union.

A few thousand years since artists first started relying on the patronage of wealthy individuals, we still have a situation where those who are most crucial to the production and reproduction of art are at the bottom of the pile when it comes to the wealth it generates. Arts workers are asking for simple things: dignity and security. Based on current evidence, it would be naive to believe such things will be kindheartedly given to them by bosses. The COVID era is not the first time that the arts and cultural sector has come under fire, nor the first time that artists and arts workers have attempted to create alternatives to the status quo. The question is whether – this time – they can build enough power amongst themselves to take what they’re owed.