To explain his objection to the term ‘outsider art’, Anthony Mannix is describing an old episode of The Simpsons. Homer tries to assemble a DIY barbecue, fails horribly, and ends up throwing a tantrum and smashing it to bits, creating a mangled mess of cement, metal and brick. As he attempts to dispose of it, the ‘work’ is spotted by a local art dealer who wants to exhibit it in a gallery. She proclaims Homer an exponent of outsider art, which, she says, “could be by a mental patient, a hillbilly or a chimpanzee.”

Mannix is curled up in an armchair at his home in Blackheath in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. The interior of his compact, one-storey, detached house has the strange effect of feeling sparse and cluttered at the same time. Drawings, paintings and books scatter the floor and shelves. The light is low and an old electric heater buzzes, even as French doors are wide open, letting in the cold winter air of the Mountains. Mannix, the house’s sole inhabitant, has smoked heavily since he was a teenager, so a light, not unpleasant, tobacco-infused fug fills his living room, in which he also works. It is an intimate, special place, and in folding himself to sit down, Mannix seems to sink into the room’s furniture and become part of its ambience. “I get around,” he says when asked how often he would leave Blackheath for exhibitions and events, prior to the pandemic, “but I could also just stay in this living room for six months.”

As one of Australia’s foremost artists from outside the mainstream institutional complex of art schools and galleries, Mannix believes that episode of The Simpsons to be a neat encapsulation of how popular thinking about this elusive and changeable category of art, also known as Art Brut, remains limited. The term ‘outsider art’ was coined by the British scholar Roger Cardinal in the early 1970s (following Jean Dubuffet’s earlier ‘Art brut’) to describe art that existed far removed from academic, traditional or establishment circles or stylistic norms. But it remains a vague and, to some, inadequate signifier.

“The terms of outsiderness should be a bit wider,” he says. “There should be more alternatives for it. And being labelled an outsider is a bit difficult in Australia because it’s a bit of a ghetto. In some ways I prefer to call myself an unconventional artist. I’m sort of off the graph.”

For all his reservations, Mannix has been dubbed an outsider artist for decades, and the categorisation is at the heart of his new exhibition with Philip Hammial, The Wild Within – Outsider Art of the Blue Mountains. In the early 1980s, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and then schizoaffective disorder, conditions that resulted in multiple stays in major Sydney psychiatric hospitals at Gladesville and Rozelle: a total, he says, of four years in batches of two to six months, over a period of 20 years. His art-making began in the wake of his psychosis, initiating a 40-year career that has yielded hundreds of exhibitions. A particular highpoint was inclusion in the historic Museum of Everything exhibition of outsider art at Hobart’s MONA in 2017-18. Regardless of labels, or the “definition ghetto” as he puts it, Mannix is a successful, revered artist at home and abroad. And he acknowledges that the ‘outsider’ tag has been inescapable, and that it has even been beneficial.

“I’ve been called Australia’s most celebrated outsider artist and Australia’s greatest outsider artist, so I guess if there’s a heap I’m on top of it. And that’s of value in some ways.

“But it’s become very popular in all sorts of media and creative terms to call yourself an outsider, which is fair enough but I think it’s a bit of a stretch in some cases and a bit facile. But I’ll take any advantage from it I can get.”

That advantage, however, has not led as far as he might have hoped: Mannix laments the fact he has never received a grant or funding of any kind: “I’ve tried, but I was pretty much ridiculed.” Given his exhibiting track record and a body of work that has attracted interest from several major institutions, this seems a particularly sad example of the art mainstream acknowledging him as occupying a valid cultural space, but not banking on him, or investing in his ‘legitimacy’.

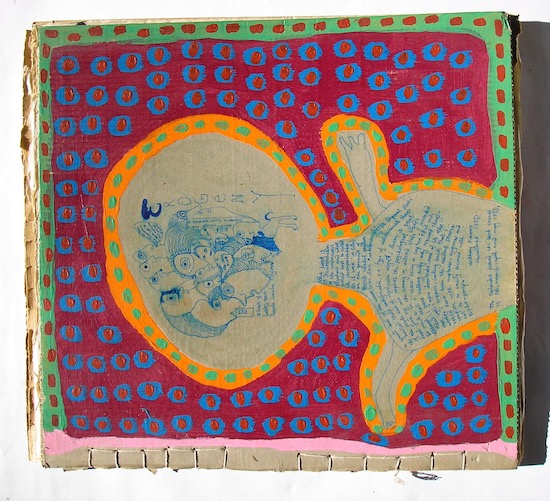

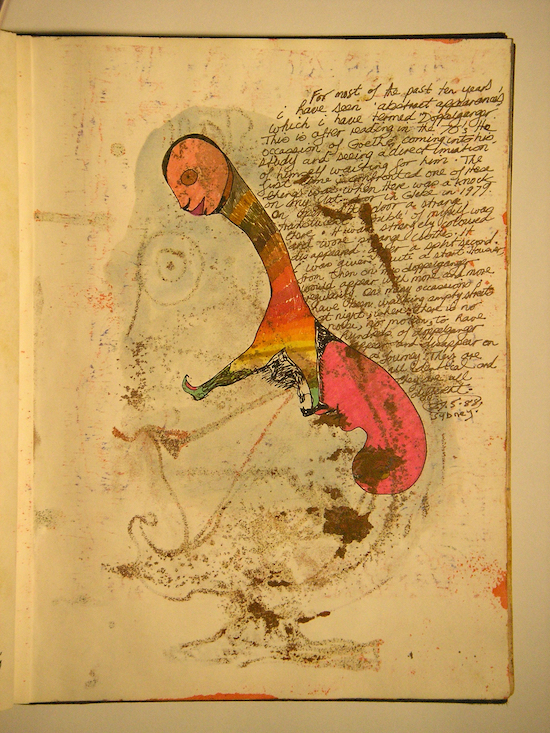

Mannix’s paintings, drawings and homemade artist books are a phantasmagoria of surrealism, featuring distorted humanoid figures, bizarre creatures and mild erotica. His idiosyncratic work is a wonder of colour and detail, while there is also a strong textual element – in fact, he recently published his first book of writings, the remarkable The Toy of the Spirit, through the small publisher Puncher & Wattman. Much of his creative output is a direct manifestation of his unconscious mind, which, he says, he “inhabited” during episodes of psychosis. And although he has not experienced a psychotic episode in over two decades, an engagement with the subconscious has continued to drive his creations. He has been dubbed the ‘anthropologist of the unconscious’ by Dr Gareth Jenkins, his collaborator and supporter and the co-editor of The Toy of the Spirit (Jenkins completed a PhD thesis on the artist in 2008, and has compiled an exhaustive online archive of Mannix’s work at www.theatomicbook.com).

“[In the unconscious mind] there is colour and plot and theme and characterisation and adventure and a sense of history too.

“One of my maxims is ‘there are only two frontiers, one is space and the other is the unconscious’.”

Born in 1953, Mannix grew up in the Sydney suburb of Canterbury. His mother stayed at home, while his father ran a small backyard engineering business that struggled during Mannix’s childhood but became lucrative later in his father’s life. During adolescence, Mannix occasionally worked for his father, an experience that he credits with inspiring some of his imagery, including an entrancing series of illustrations in The Toy of the Spirit made up of fantastical mechanisms, devices and diagrams. “Since I saw machines, I would think machines,” he says.

Mannix received a Catholic education that didn’t stick, before attending technical college and then working as a public servant for two years. He went on to study Cultural Anthropology at Macquarie University but, again, the confines of institutionalised learning didn’t suit him and he dropped out. He also travelled in Asia for two years amid all this, including a 14-month stay in Java.

“I came into contact with all the ancient temples and monasteries, and I always had a dream that I’d go back and draw them – and this was before I could draw. I was also very interested in shadow plays. In fact, if you look at all the figurative work I do, they all look like shadow puppets – they’re my version of shadow puppets.”

Mannix’s first experience of psychosis came when he was 22 years old, with his first works of art following soon after.

“It hit in 1976 and then in 1977 and again in 1980, so I knew it was set in. By the time I was 25 I knew it was going to be a very different life and that I better adapt. By the time I was 30 I really had things to say about it.

“All the art came out between 25 and 30. I didn’t have it before psychosis hit, but I did after, so it was undeniable where it came from.”

His first exhibition came in 1980 at the now-defunct Outsider Gallery in Balmain in Sydney, setting him on an artistic path that has certainly given expression to those “things he had to say”.

One of those things concerns the concept of what he terms the ‘irreal’, an idea that ripples through The Toy of the Spirit. His formulation of the irreal reflects his forthright belief in the authenticity and reality of the psychotic experience, and the impressions and perceptions that come with it.

“The thing about the psychotic experience that is generally not realised by the layman is that, to you, the experience is real, even if to somebody else it might seem just gibberish if you describe it. The experience is what Gareth calls ‘lived metaphor’, and it’s of the same value as experience. The irreal is that different avenue of perception – augmented perception.

“The squeal of a car becomes a voice inside your head, and that becomes a sentence, a piece of poetry or an instruction, a message, it could be anything. The irreal involves the coherency of those different perceptions and illusions.”

Another central tenet of Mannix’s personal philosophy is an acknowledgement of the duality of his condition. Of course, madness is, as he puts it, “a really lousy hand of cards”, but he also places a certain value on it. Mannix has befriended madness, exploited it, ridden it, taken solace in it and, of course, made it the source of his creative impulse.

“The Romans used to call schizophrenia the divine sickness,” he says. “Mind you, it is a sickness, and that’s pretty unavoidable. The structure and cosmology that I’ve put together wouldn’t exist without psychosis. I would have been left a rather mundane, unthinking, uncultured, socially inept public servant. I admit that I don’t have the superannuation [pension] that I would have liked, but it’s been a really rich and augmented life. And psychosis was probably my only entrance into culture.”

Indeed culture, in its broadest terms, is something Mannix actively engages with. So perhaps he isn’t that much of an outsider after all – he is not the reclusive hermit that label might imply, as a couple of hours in his company will prove. He has a wide circle of friends and associates and is up to date on current affairs, including issues regarding COVID-19. He has been the subject of several ABC radio documentaries, and a television documentary, directed by Kasimir Burgess (The Leunig Fragments), is on the way – as are more books. He also demonstrates an attuned socio-political awareness in acknowledging that some of the more sexually graphic aspects of his art and writing – an eroticism that he describes as “soft and sweet” – might fall foul of progressive politics today.

And he is a fan of The Simpsons, sort of, even if he is a little envious of Homer in that episode, when he becomes the toast of the Springfield art world without trying.

“Homer was discovered, and that’s the dream of any artist.”

The Wild Within – Outsider Art of the Blue Mountains, is at Disorder Gallery, Sydney, from 25 March until April 10