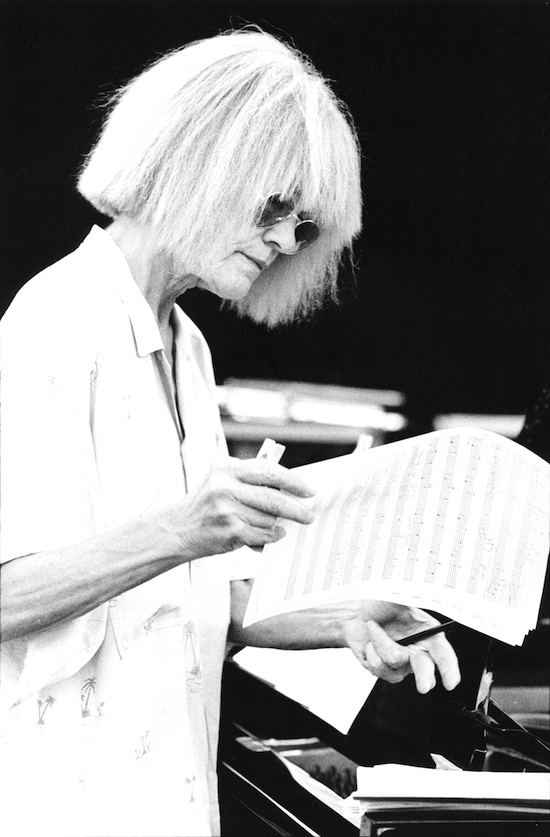

Carla Bley by Elena Carminati

Edward Said immersed himself in the final works of Beethoven, Genet and Beckett while writing his own last book. Said, who produced On Late Style while ill with leukaemia, concluded that at the end of their lives, artists did not tend to resolve issues that had preoccupied them for their entire practice but instead produced works of unparalleled complexity and unresolved contradiction.

Theodor Adorno, who coined the phrase “late style” when writing in 1937 about the “third period” of Beethoven (which concluded with the notorious Grosse Fuge), also resisted the idea that work necessarily became simplified as the years stacked inexorably up.

However slippery a concept “late style” actually is – can we talk about Mozart’s late style when he had the misfortune to die so young? What about the late period of Captain Beefheart, given that Don Van Vliet gave up making music nearly three decades before passing on? – many would agree that while not imprinting a valedictory full stop at the end of a career, the final phase does see a stripping away of extraneous experimentation and unnecessary adornment, to be replaced by a fierce concentration: a distillation of the most necessary themes and ideas. While late style can seem old-fashioned and out of step to younger observers, it can still often predict great stylistic shifts ahead for genres as a whole.

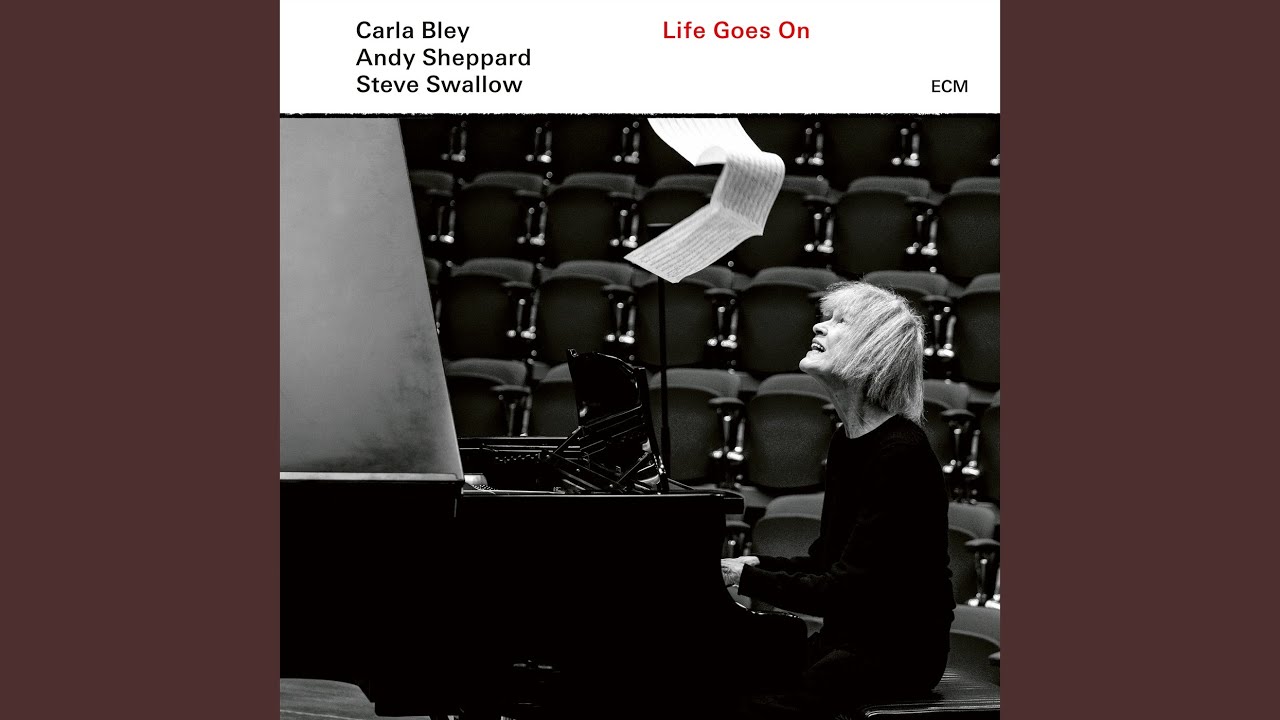

The American composer and pianist Carla Bley has had an extraordinarily long career by any standards – and I sincerely hope that it continues onwards at full strength for many years to come. But at one point not so long ago, her 2020 album Life Goes On must have seemed an unlikely proposition. A career that has included nearly 30 albums with her as lead musician, more than 30 collaborative albums (including glorious stints with both the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra and Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra) and six decades’ gainful employment as a jazz composer was brought cruelly to a halt by a bruising tangle with brain cancer in 2018.

She says: “I have a little piece of my brain missing. They operated on me about three years ago. Sometimes I don’t know the answer to a question, so I think they must have taken something out by mistake, because ever since the operation I no longer have perfect pitch. There was a tumour on the tip of the occipital lobe of my brain. I think it was caused by working on three different musical formats at once… it just about burned a hole in my head! So they took it out, but there have been a few things that haven’t been right since. I can’t see the note on the far left of the score until I move my head over there and… what else? Terrible things… some terrible things.”

But then she brightens: “But I can’t remember what they are. Anyway, that’s enough of that… mood.”

Thankfully, she has recovered enough so that the enforced break was only temporary. The trio she formed 27 years ago with bassist husband Steve Swallow and saxophonist Andy Sheppard got to record one of their crowning long players in Life Goes On.

She’s having to isolate now, of course, but given that she lives in rural upstate New York, this is easier for her than for many of her peers, as she admits. Her and Steve have had friends get ill with Covid-19; her European tour manager, John Cumming of the London Jazz Festival, and Hal Willner both died after contracting the virus: “Something we’ve become aware of acutely during this crisis is our privilege.”

Perhaps unavoidably, the idea of mortality informed the writing of the opening suite of tracks: ‘Life Goes On’, ‘On’, ‘And On’, concluding with the remarkably buoyant and slightly mischievous ‘And Then One Day’. The first of these is a masterfully languid blues which isn’t riven with fearful complexity, but is delightfully concentrated in form: “I wanted to write a simple blues, but it didn’t come out simple. It got more complicated as it went on… as does life.”

Carla says that while she doesn’t usually remember “dark thoughts”, she did in the case of ‘Life Goes On’, but rejects the idea that writing the music formed any part of her recuperation: “It was mindless. It’s just what I do. And it’s what I’ve done for 60 years now!”

She, probably doesn’t suffer fools gladly and is quick to pull me up on any misconceptions I have, although she isn’t rude about it. However, she sounds delighted when I mention late style: “That is a great, inspiring thing to hear. Steve has been telling me for years about Bach and Beethoven and how their later stuff affects him the most effectively and most tremendously. He loves those swan songs. So I already knew about late style. And I didn’t ever think I would live long enough for this idea to affect me. When I was younger I thought I would die at 30 because I was really living hard and not taking care of myself, and sometimes I didn’t even wanna be alive. You know how it is when you’re 30!”

It’s interesting to note that while members of her various bands have sometimes referred to her affectionately but tellingly as Countess Bleysie, one of Steve Swallow’s uxorious nicknames for her is “Bleythoven”.

Elsewhere on Life Goes On, the ‘Beautiful Telephones’ suite makes oblique reference to the recently retired US president, Donald Trump, looking back to his first day in the White House. She explains: “I was amused, and a little horrified, that when Donald Trump visited the Oval Office for the first time, he noticed a lot of things around him, he saw paintings by famous artists of famous presidents, he probably saw beautiful rugs on the floor and all of these things, but I would have thought he would have been thinking of something important. But his only comment about what he saw was ‘beautiful telephones’. Um, I got a chuckle outta that.

“I remember speaking to the audience at a show about that tune and saying, ‘Well, I love things like beautiful telephones,’ but I’m not the president! He’s supposed to be thinking about other things.’”

But if Carla Bley can be judged a political artist working in a mainly instrumental field when viewed through a certain prism, there’s more supporting evidence for this than just the odd titular hint. ‘Beautiful Telephones’ contains a wealth of commentary woven into its score. There is an interpolation of the conservative anthem ‘You’re A Grand Old Flag’ – a musical echo of her work on ‘Circus ’68 ’69’, from Liberation Music Orchestra, which we’ll get to in a bit – raising the question: why do these particular patriotic little excerpts insinuate their way into ‘Beautiful Telephones’?

She says: “These tunes can appear unbidden… Something like ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ can appear in your [internal] jukebox and that jukebox contains things you’ve been hearing since you were a small child. So when one of these songs occurs to me, I usually put it in the score. I chuckle and put it on paper.” But the reason why she does this is perhaps even clearer when the suite ends with a few bars of ‘My Way’. Donald Trump, Mike Pence and their wives danced to the song at the 2017 inauguration. As Steve Swallow reminds me, the day after the interview, Nancy Sinatra subsequently tweeted and then deleted an exhortation to Trump: “Just remember the first line.”

Carla is nothing if not realistic about what all of this means though: “I love the idea of providing a thorn to stick in any part of Donald Trump. And I can think of some good parts to stick it in. But I always said that I don’t think writing a piece of music about a person would make them any better. Y’know: ‘Here’s a piece of music about Hitler… maybe it’ll make him better.’ It’s just showing where your own interests, hopes and desires lie. But music, I think, is mostly like preaching to the choir.”

I’m loath to disagree with her but a look at her extensive and wonderful body of work – and a close look at the way she has operated and organised professionally – suggests that there is a radical zone that she has successfully operated in over the space of a lifetime, comfortably between the two poles of unrealistic idealism and empty gesture.

Carla during the recording of Life Goes On courtesy of Caterina di Perri/ECM

Carla was born Lovella May Borg on 11 May 1936 to Swedish-American parents in Oakland, California. Her mum and dad were Christian fundamentalists and she was exposed from an early age to religious music in church and classical music at home. When she was very young it became clear she had perfect pitch and a natural inclination to play: she says her first piano recital was to her parents at the age of three (albeit one played with clenched fists).

She received some beginner’s piano tuition from her father Emil but this did not last for long. Her father became exasperated at her lack of progress and ceased teaching her at the age of seven: “Then my mother tried to teach me but I bit her! And that’s family history now, the fact I bit my mother, when she told me I needed to put a sharp in front of the G. I didn’t have the patience for the lessons, so I developed on my own in an unsupervised way.”

While only eight or nine, she became obsessed with the music of Erik Satie, an obsession still obvious in her work today: “Erik Satie was my only influence then. He influenced everything I ever did afterwards. But when you’re 13, you’ve got to watch out what you listen to. I recorded Parade off the radio but it was the only tape I had, so I really learned it.”

Her introduction to the world of jazz was low-key. Her friend Sylvia had elder brothers who had records and a desire to impress her. She was taken on a date to see a large show by Lionel Hampton at the Oakland Auditorium and later a visit to San Francisco bar, the Jazz Workshop, to watch Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan. She enjoyed the show but admitted that it didn’t convince her about the idea of improvisation; the technique seemed to her at the time like an “obstacle” rather than a means of liberation. She laughs and says: “I think I liked Chet Baker better than Gerry Mulligan because he was more attractive, although later I would think that not only was Gerry Mulligan more attractive but also a great musician. I had no idea how great he was then. I mean, Chet was cute but Gerry Mulligan, man… could he write for a big band… he was a great writer. Anyway, that show was a big deal in my leaving church music behind and going to the music of the devil.”

Just months after quitting the church, she also dropped out of high school at the age of 14 with no qualifications. She spent some time as a pianist in Monterey and San Francisco playing in bars that she was far too young to drink in. Her idiosyncrasies as a player and standoffishness about improvisation didn’t win her that many fans among the patrons of these establishments, and a year or so later, at the age of 17, she hitched a ride with a friend to New York because she wanted to watch Miles Davis play at the Café Bohemia.

The trip proved to be a life-changing decision. It was simply necessary, however: “I went to where jazz was a big deal and being made. In Oakland at the time, it was just something that came through town. I just felt like the West Coast was not where it was happening, and even the guys that I managed to see, like Chet Baker, came from New York. So that was where I had to go.

“While I was playing solo piano at the Black Orchid, SF, I met the son of the concertmaster at the Boston Symphony Orchestra and we both decided we had to go to New York. A guy who came with us had a Mobil credit card and that’s how we lived. We just bought gas and whatever the gas station sold as food and drink, which was sometimes a sandwich or most likely just a Coke.

“There was no romantic relationship between me and the boy. I slept rough at Grand Central Station when I got there. I headed straight to where I could hear the music and that was Birdland. I had to lie about my age to get a job as a cigarette girl there. But I got to see Miles Davis play. Paul Chambers would have been playing with him. Philly Joe Jones was playing too because he did his ‘Blues For Dracula’ bit. What was he like? Honestly? I was a little bit horrified because I thought he would have been more serious than that!”

She looks at this visit to Birdland as being her first serious step on the road to becoming a composer: “Listening is how I started. I didn’t start when I was a piano player. I didn’t start as a composer. I started as a listener. And I listened for a long time before I did the other stuff [properly]. I consider Birdland my entire education… well, maybe not basic learning – I didn’t learn to read or write at Birdland, but that’s where I learned everything else!”

And what listening there was to be had at the Broadway and 52nd venue. Count Basie. John Coltrane. Stan Getz. Dizzy Gillespie. Charles Mingus. Lester Young. On top of this, through the club, she met the established Canadian pianist Paul Bley and they became a couple. She celebrated her 21st birthday by officially changing her name to Carla Borg and, more importantly, she started composing regularly.

The way she tells it, it feels like it was hard for her to leave her front door in NYC without bumping into some legend or other. The couple ran into Louis Armstrong and his wife at a subway station in Manhattan. (“It was mostly Paul talking, but Louis was polite. Nice people, I thought.”)

And haven’t I got it right that Charles Mingus gave you the glad eye?

Carla says: “The glad eye? You mean like, he tried to pick me up? Well, that’s what I thought at the time… but actually he never did. He made a suggestion, ‘How would you like to play with me?’, which I took completely the wrong way…”

The couple then moved to LA. Paul Bley’s 1957 album Solemn Meditation was an important milestone for Carla, as it contained her first mature composition, ‘O Plus One’, a play on the words “opus one”. In autumn 1958, Paul Bley ended up with a residency at the LA Hillcrest Club, playing with a quintet made up of him, Charlie Haden on bass, Ornette Coleman on sax, Don Cherry on trumpet and Billy Higgins on drums. They were playing an emerging form of music that would become known as free jazz. Carla attended the sessions to listen: “I recorded them, but I was sitting under the piano with a tape recorder, because Paul Bley wanted them recorded. I wasn’t at a console in a studio or anything.” As you would imagine, the sessions themselves didn’t feel unusually momentous at the time.

“There was no discussion,” she remembers. “I never really knew Don that well, even though we did a lot of tours together. Charlie Haden I knew very well. Billy Higgins was approachable and we hung out together at the Hillcrest Club but I wasn’t working there, I was just listening.

“Ornette was a lot more approachable. Both Ornette and Don once played a tune of mine called ‘The Donkey’ but they played it a half a step high, because Ornette played so sharp, and Don didn’t mind playing sharp. I was playing the piano, so I just changed from the key of F to F sharp. And then it just kinda morphed into a blues in the key of F. But that was the one time. They just happened to be round my house…”

I have to ask if there was any talk at all at the time about these foundational free jazz shows from anyone involved, but she’s adamant: “Absolutely not.”

But what about from Paul maybe?

She laughs: “Well, Paul was forever talking about one thing or another, pontificating most of the time. I put up with it, but I never spoke. Well, I guess maybe I did say something in return, like: ‘Yeah Paul!’”

The Hillcrest quintet mainly played Ornette Coleman’s music but they also played Carla’s, meaning her first significant writing work was composing free-jazz “heads” – the thematic melody, often the opening riff or section of the piece – for small groups to improvise around. This was a form she sometimes refers to as “miniatures”. It was something she would stick with for the duration of her marriage to Paul.

Steve Swallow, Andy Sheppard and Carla Bley by Bill Strode

To outsiders or neophytes, the idea of composing for free jazz can feel vaporous, a contradiction in terms, even. Carla explains her relationship to the discipline: “I once said: ‘I never wrote a song past the age of 17 that didn’t include improvising.’ And it’s true. When you have a really great improviser, they will play your tune again and again but totally differently each time. Each time there is a new variation. Your music inspires a guy to play… to develop something new. Not everyone does it, but boy when it happens, that’s a great thing. So when the musician knows what you have written and plays it as though it inspired them…”

She pauses and laughs softly before continuing: “… and maybe it did, maybe it didn’t. Whatever. I was writing music for someone who needed it. Or who I imagined needed it, or for someone I assumed would understand that they could not continue without playing my changes [laughs].”

But how did it work in practical terms? If you wrote a short head that lasted for 30 seconds and then there’s a 20-minute improvisation by a different musician, would you have gotten all the writing royalties when it was released on record?

She replies brightly: “I would have done. Isn’t that wonderful? What a racket!”

The sheer newness of the music got the band of musicians fired from the Hillcrest Club after a couple of months. Paul and Carla married in Carmel, California, she took the name she still uses today, and, fired up about this energising development in jazz, the newlyweds moved back to New York. Thanks to the public enthusiasm of not just her husband but a young, up-and-coming bassist called Steve Swallow, word of Carla’s compositions started to spread. Her work was soon also being played by George Russell, Gary Burton, Art Farmer and Jimmy Giuffre.

Carla has had three major relationships in her life, all with musicians that she’s worked with and written for intensively. Has there ever been a divide been the domestic and creative life for her, I ask, or has it always been one and the same thing?

Carla laughs: “Well, I just stayed with one man until I couldn’t get any farther with that man and then I’d switch to the next man and go with him, and I ended up with Steve Swallow!”

At this point Steve chips in: “And he won’t leave!”

Carla is quick to reply: “He doesn’t have to leave… yet.”

From 1960 onwards, Carla and Steve began playing as a duo in the “new jazz” venue and Bleecker Street coffee house Phase 2. Their pay? Five dollars and a meal. That year also saw the first physical release of one of her extended compositions. ‘Bent Eagle’ is a track on Stratusphunk by George Russell, the author of one of the first serious books on jazz theory, Lydian Chromatic Concept Of Tonal Organization. She says: “It was significant for me. George was like a composer’s composer.”

But not only that, it had arrived at a crucial juncture when her self-belief was being tested sorely: “I’d been to see a psychiatrist and happened to mention that I was a composer, and he said: ‘Maybe that’s the source of all your problems. Why don’t you just get rid of that illusion and think more honestly about what it is you do. You’re a waitress! You’re a cigarette girl at Birdland.’ He said I should go and look for a job as a seamstress, so I went to the garment district to look for work because I thought that sewing was the only skill that I had. I went to the garment district, sat there in a chair waiting to talk to a designer who never showed up. Finally I just left. And then George Russell called and asked if he could record ‘Bent Eagle’. So I was rejected by the garment industry and accepted by the music industry all in the same week. And that’s what finally started me off.”

By the mid-60s, the Bleys were a power couple in the world of jazz and they, along with many of their contemporaries, were undoubtedly worried about the status of their music. It was a subject they discussed regularly with the likes of Albert Ayler, Roswell Rudd and Cecil Taylor. Formally, jazz was going through revolutionary changes and lightning-fast evolution, but its star was waning in commercial terms. Records were selling fewer copies and it was harder to sell out shows. The perception was that damage was being done by insurgent pop forms such as rock, R&B and soul music: “All of a sudden I was told by an artist friend of mine that jazz was dead, that now it was, y’know, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles and the type of music that was still called pop.”

Carla was very much at the vanguard, in New York, of attempts to recontextualise the six-decade-old genre of jazz as music reaching full maturation and the apogee of its exciting avant-garde potential simultaneously. She was involved in both the October Revolution In Jazz concerts at the Cellar Cafe and the Jazz Composers Guild – effectively a short-lived but important labour union for avant-garde jazz musicians.

Carla says: “I wanted to object to as many things as possible that were wrong in the world of jazz and change the whole system that existed in the music world. I came from being this cigarette girl and cloakroom girl working for the mafia. They made me hand in my tips, and if I didn’t make up $25 in tips they took it out of my salary. I mean there were a lot of things going on in the music world that involved club owners, concert producers, and record companies… whew-eee! Definitely the record companies! The record companies decided what music would be in and it was decided on the basis of: ‘Well, this ought to sell some biscuits’ and ‘That person is very attractive’. And I just wasn’t a follower, I was trying to be a troublemaker and trying to change the ways of the world that I didn’t agree with. I was at that age, I guess.”

Carla Bley by D. D. Rider

The Guild included, among others, the Bleys, Rudd, Archie Shepp, Carla’s soon-to-be second husband Michael Mantler and Sun Ra. For the leader of the Arkestra and self-styled visitor from Saturn, the mission was more important than the man, and was definitely more important than the woman. He objected to Carla’s membership of the Guild strenuously on the basis of her gender.

She explains: “In one meeting, Sun Ra said aloud to all the members of the group that I would sink the ship because that’s what women do. I was furious. I got up and said, ‘You son of a…’ I really yelled at him. And then he said: ‘Yeah, of course you’re yelling at me. You’re the white woman yelling at the black man.’ I said: ‘Oh my god, that sounds so awful, I can’t bear thinking about it.’ So I got up and left. But I called back half an hour later and Archie Shepp answered the phone. I said: ‘I’m sorry I left. I’ve been thinking about it and I want to make friends with Sun Ra. I understand his point of view. I’m mortified at what I must seem to be – at what I am – I’m angry at myself!’

“So I went back to the meeting, everybody accepted me back and Sun Ra didn’t say anything mean, so I was back in. Sun Ra and I did get along from that point on. I think we were polite to each other and I still really loved his bands. I have no idea what he thought, though. But I thought that he was both great musically and seriously behind the times as far as gender was concerned. But, you know, I should have gotten used to it over the years: being kicked out of things because I was a woman. But I also shouldn’t have gotten angry at him. I should have been reasonable and said: ‘Well, I don’t agree with you Mr Ra!’”

The Guild was formed against a backdrop of war being waged on civil rights protesters by brutally reactionary police and the National Guard. The musicians were operating from a position of collectivism, but not all of the egos contained within such an ad hoc labour union were ready to act for the greater good of the whole, and it didn’t last long. The group did, however, clearly generate several groundbreaking creative strategies for dealing with “the threat to jazz” and led directly to the foundation of the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra Association – and it was through this large ensemble Bley would record what is, to many fans, her defining work, Escalator Over The Hill.

Carla wrote short, minimalist heads for free jazz while she was with Paul Bley, primarily because that’s what she was asked to write for him. But when they divorced (Paul would go on to marry another groundbreaking artist, Annette Peacock) Carla got together with Michael Mantler, whom she also wrote for, and suddenly her work typically became about long-form big band pieces.

She explains: “Well, I wrote for people who asked me for music and those shorter pieces were what Paul needed. So Paul Bley would say: ‘I got a day recording tomorrow and I need five tunes.’ That actually happened once. So, yeah, I wrote them all overnight.

“Being a jazz composer is like a service occupation, and that was especially true in the 60s when free jazz was in its ascendency. I would say to anyone who complained about a tune that I wrote: ‘Look, I’m a jeweller and I’m setting your stone, so shut up!’”

If Carla had a road-to-Damascus musical experience as an adult, it was when she heard The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967 as she started to tire of the all-out assault of free jazz.

“The Beatles were forced on me by Michael Snow, a sculptor living in New York,” she says. “He was in our circle. He knew Steve because they both had lofts down by the World Trade Center that were right next to each other.

“Mike came to my house one day and said: ‘Oh, it’s the most startling news! Jazz is dead. The artists don’t like it anymore. They’ve switched to The Beatles.’ He took out this album that he’d brought with him and slapped it on the turntable, and I listened to the whole thing and said: ‘Wow.’ I thought ‘A Day In The Life’ was really good. I was sold. I said: ‘OK, no more jazz now. I’m going to become a pop musician.”

Whether the album that sprang directly from this exposure – The Gary Burton Quartet With Orchestra’s A Genuine Tong Funeral (1968) – is pop or not is highly debatable, and indeed is debated even by Carla herself: “Of course, I couldn’t really become a pop musician, but my efforts led me into a few directions that were interesting, I thought.” The influence of Sgt. Pepper’s can be heard most directly in the fact that this is a concept LP. Steve Swallow told his then bandleader Burton about the project Carla was writing and he facilitated a release of the “dark opera without words” via his record label RCA. The music was written to be staged with a light show and musicians wearing outlandish costumes, a reflection both of the psychedelic rock gigs of the day and a sign of what was to come. In stark contrast to most jazz of the day, the music was almost totally scored, and scored exquisitely, for the specific musicians making up the quintet, rather than generically for their instruments.

Carla was galvanised by the creative success of A Genuine Tong Funeral and she describes the actual birth of Escalator Over The Hill, both as something triggered by it and as a “magical moment”.

She explains: “I had been working on a piece of music called ‘Detective Writer Daughter’ and my friend Paul Haines sent me a poem. I put the poem on the piano. It was like a score, but instead of notes, it contained words. I looked at the poem and started playing the piece I was working on, and the words just fit so perfectly. It was one of those nice moments. When that happens, you’re awfully happy, you know. So I wrote back and I said, ‘Let’s write an opera together.’”

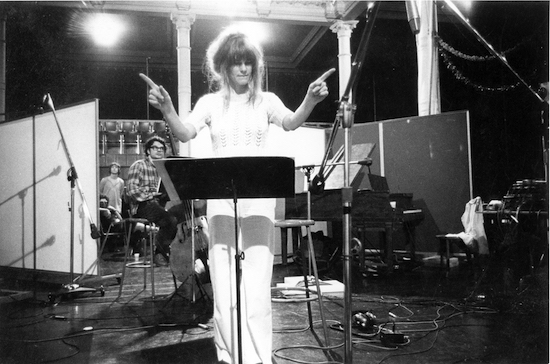

Carla conducting during the recording of Escalator, by Tod Papageorge

Carla originally met Haines at the Jazz Showcase in New York, where they had bonded over a love of Charles Mingus before he left to start a new life in India, but the pair remained pen pals. She hadn’t yet written music to go with lyrics as an adult but wanted to work with Haines, who sent her a full set of surrealist verse for a new project. As Carla then had little interest in the meaning of lyrics, this style of writing probably suited her the best: “It was so simple, the way that music came to me just by looking at the words. I think anyone would find that if they wanted to write a piece of music then they should start with the words, because it almost gives you all of the notes. And in this case, if I didn’t have the words for what came after a certain section I’d been working on, I’d just give a trumpet solo to Don Cherry!”

The writing took place on the farm outside Bangor, Maine, where she and Mantler lived, but the recording mainly took place in NYC at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater and the RCA Studios – although RCA themselves didn’t fancy taking a punt on this LP, which was growing rapidly into a huge project. Escalator hadn’t started big but it just kept on expanding and expanding. The more the project expanded, the more labels turned it down; the more labels turned it down, the bigger it was free to get.

Before long the pair had ceased calling Escalator Over The Hill a jazz opera and moved on to the altogether more highfalutin’ term chronotransduction, a term devised by a scientist friend of Paul’s called Sherry Speeth. Speeth had earned himself renown and a lot of money for developments in the field of nuclear detonation detection, devising a way of converting seismograph readings into audible recordings, which allowed the listener to be able to distinguish between earthquakes and illicit nuclear tests: an invention crucial to the success of the nuclear non-proliferation pacts of the 1960s and beyond. As well as donating a new genre tag to the project, Speeth – perhaps more significantly – also donated $15,000 of his wealth.

Carla remembers: “Twenty years later he was broke, and Paul Haines said: ‘Could we give him the money back?’ I said, ‘We don’t have it, we spent it!’” And Steve adds: “God yeah, but Escalator came out of it… one would have to say it was money well spent.”

As for the highfalutin’ name, she adds: “When I asked Sherry what kind of work he was in he told me he was a chronotransducer. So I said: ‘OK, duce means ‘lead’, trans means ‘across’ and chrono means ‘time’. Time travel… that’s what chronotransducer means. So since what we were doing didn’t really sound like most opera, I wanted to give it a new name. We called it a chronotransduction so it wouldn’t get compared to Aida, essentially.”

Despite Sherry’s largesse, money remained a problem during the three-year period the album was recorded in, with no record label to underwrite the huge cost. A friend of Carla’s helped her secure a crucial $30,000 bank loan, and Haines wrote numerous letters to famous leftfield artists (usually to no avail) in order to fund the project. The suspicion remains that if they’d raised more money, perhaps today we’d be discussing a quadruple or quintuple album instead of a triple. (As it was, the project nearly finished Bley and drove her $90,000 into debt.)

But its dimensions are jaw-dropping enough. Escalator Over The Hill was eventually created in three continents by a cast of more than 50 people and took almost five years to finish.

Whether you refer to the treble album as a jazz opera or a chronotransduction, neither really gives the first-time listener a good idea of the ground covered in its 100-minute running time. They are exposed to big band jazz, Kurt Weill-style Weimar drinking songs, experimental synthesizer soundscapes, Indian raga, pounding rock & roll, heavy psych fusion, opera, music hall comedy, free jazz and spoken word, from a cast of musicians and actors that included Jack Bruce of Cream, John McLaughlin of Mahavishnu Orchestra, Paul Jones of Manfred Mann, Don Preston of Frank Zappa’s Mothers Of Invention, Viva (the heavily pregnant porn star and member of Andy Warhol’s Factory), Linda Ronstadt, Charlie Haden, Gato Barbieri, Jimmy Lyons, Dewey Redman, Roswell Rudd, Paul Motian, Michael Mantler and of course Don Cherry. It was, as writer Marcello Carlin suggested in 2007, as if Bley had set out to sum up everything musical that had happened so far in the 20th century.

Like most members of the Jazz Composers Guild, Carla had her own ideas about how people from the world of jazz should be dealing with the “threat” posed by popular music, and arguably her reaction, in the form of Escalator Over The Hill was even more radical than those new solutions dreamt up by Sun Ra and Archie Shepp, both of who responded sublimely in their own ways to the arrival of soul, funk and disco. But the sheer amount of time it took to make the album meant a lot of the immediate cultural impact Escalator could have had was dissipated by the day of release. During the time Carla, Paul and the JCO were working on their explosive version of what fusion meant, Miles Davis recorded In A Silent Way, Bitches Brew, Jack Johnson and Live Evil. The answer to jazz’s existential problems of the late 60s had clearly been found outside of the Jazz Composer’s Guild in these revolutionary grooves. The truth is that, Escalator’s brilliance notwithstanding, even Carla Bley herself worked on a much more immediately influential album during this period: Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra (1970).

Carla first met Charlie Haden in 1957: “He came to Los Angeles when he was 16, met Paul Bley who hired him to work in his band at the Hillcrest as his bassist. I came to work with him after he called me. I think he was impressed by A Genuine Tong Funeral.”

Carla Bley became, to borrow the author Amy Beal’s wry term, the “lone arranger” for Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra from its foundation in 1969 until his death in 2014, and beyond. She facilitated his vision of melding revolutionary-in-message protest music to revolutionary-in-form free jazz by having the sheer breadth of vision and depth of ability to arrange and orchestrate everything from the work of Haden, Ornette Coleman, Pat Metheny and Bill Frisell to that of Dvořák and Samuel Barber, not to mention skilful quotation from and adaptation of Spanish civil war anthems, South American folk music, the work of Bertolt Brecht and Hanns Eisler and standards such as ‘We Shall Overcome’ and ‘Amazing Grace’. Beal notes that although not so outspoken about politics herself, the amount of time that Carla has dedicated to this project over a 50-year period speaks volumes in itself.

The Liberation Music Orchestra was formed at the height of the Vietnam war and was intended, unambiguously, to amplify the voices of those affected not just by this conflict but by racism, mental illness, unemployment and drug addiction. Haden, an impassioned man, was always willing to put his money where his mouth was. While on tour with Ornette Coleman in 1971 in Portugal, which was under fascist dictatorship, he dedicated ‘Song For Che’ to anticolonialist revolutionaries at large in the Portugese colonies of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea. He was arrested at Lisbon Airport the following day and interrogated by the Portugese secret police, the DGS, and only intervention by the American cultural attaché to Portugal secured his release. Haden was grilled by the FBI over the meaning of his dedication on return to the States.

‘Song For Che’ is just one of the radical tracks on the band’s self-titled debut album from 1970 – and the intent is clear: to make a music that is revolutionary in form, content and intent while drawing clear links between various liberation movements globally both past and present. One could say that as a piece of chronotransduction it’s just as successful as Escalator, if not more so. As mentioned nearer to the the top of this article, the album “quotes” various standards and political songs. As jazz is a genre that relies on quotation and citation this is to be expected; however some of the inclusions were of original recordings first made in the 1930s, and these “samples”, juxtaposed with the free playing of the band over the top, are what contributed to making this album a unique jazz milestone when it was first released. These sonic “clashes” were meant to give vigorous representation to the chaos around the musicians. The track ‘Circus ‘68 ‘69’ turns the sound of the 1968 Democratic National Convention descending into chaos into a thrilling sonic battle. After a vote on Vietnam was lost, delegates began to spontaneously sing ‘We Shall Overcome’, in protest and the convention orchestra was commanded to drown them out by playing such conservative tunes as ‘You’re A Grand Old Flag’ and ‘Happy Days Are Here Again’, while the police were called in to restore order. And all of this is faithfully reproduced in the push-and-pull and tumult of the song scored by Carla.

Carla talks about this album in terms of the origin point of an ongoing political awakening: “Charlie had these one-way discussions about politics with everyone. And most of us sidemen who were recording the first Liberation Music Orchestra album? None of us knew who he was talking about. We were just kind of coddling Charlie, and every time he’d mention these people from the Spanish civil war we’d say, ‘Yeah, that was really happening’, or, ‘Boy, those songs were really great.’ We thought they were OK, but we just didn’t have any political intent. I think all of us shared the desire for the world just to be musical, and the idea of politics didn’t really come until after we were exposed to Charlie. But he planted the seed, and by the time Not In Our Name came out, we were all diehard political nuts. He was our father. He started us off on that quest.”

Perhaps understandably, the project is currently very close to the surface in her mind. Not only has the music not felt so timely for many years, but at the time of interview, band member Bob Northern had just died: “Boy, it just pervades everything doesn’t it? It pervades what’s happening in life at this moment for everybody I know… the coronavirus and Black Lives Matter. Bob Northern was in Charlie’s band for a long time. I never went to his house but I felt like we were friends.”

But even though Charlie Haden passed on in 2014, it hasn’t been the end for Liberation Music Orchestra – just as life goes on, the music also does: “I wrote ‘Time/Life’ when Charlie Haden died. I was in the garden when his wife Ruth Cameron called me and said: ‘Charlie’s gone.’ I said, ‘OK hold on, I’m in the garden. I have to absorb this indoors, I’ll call you later.’ Then I went indoors, sat down at the piano, and the very first chord of ‘Time/Life’ occurred. I just put my fingers down on the piano and there it was. And I said: ‘That chord is a Charlie chord, he loves it when you put the root in the third… the first inversion. He loves that, so that’s how it will start.’ I don’t even know if I called Ruth back. I just sat there for days… months even… just writing ‘Time/Life’.”

The composition formed the title track of the Time/Life album released on Impulse! in 2016. But even that isn’t the end of Liberation Music Orchestra: the message is carried forwards because it is possessed of a vigour beyond the input of any of the individual members, while still celebrating the vision of its founding member, guided by the skill of the “lone arranger”. Carla explains: “The music is really on my mind these days, and it’s on the mind of Ruth as well, because she was married to Charlie for 20 years. She wants to keep his name alive, so we’ve been doing gigs. Steve plays bass instead of Charlie now. So for the last couple of months I’ve been working on Liberation Music Orchestra music. Ruth called me and said: ‘It’s Charlie’s birthday in August and I want to do something for him.’ And I realised that Ruth is interested in Charlie having a day, like Martin Luther King Day, but in the musical world – Charlie Haden Day, wouldn’t that be great! So we said yes, because she misses him terribly and she’s on his team. And we’re on her team. And we’re on Charlie’s team. And now we’re recording new music by Zoom. I had to learn how to play to a click track. Steve went first. Then me next. The piano goes on as a sort of guide so that people can keep in tune, cos if you don’t play all together, sometimes you go out of tune, you go off on your own little scale or something. So then we sent it to the engineer, and he sent it to all the guys in the band and they each put on their part. It starts with ‘Time/Life’ and then it goes into a blues, and then into ‘We Shall Overcome’. So it’s a three-part piece!”

Carla Bley by Bill Strode

She agrees that for the last few years, the idea that she has to get music recorded now because there is less time in the future has started to occur to her: “I had about ten pieces of music that I had written [before getting ill] and they had never been recorded or released, and I was very anxious about them. I just wanted to get them done and put a period on the end of things, or hopefully an exclamation mark. Anyway, I’ve now recorded a few of those, The French Lesson is one of them.

“It was about three years’ worth of work. I wrote it for a big band and boys’ choir and recorded it in Germany. My producer, Manfred Eicher of ECM, just hated the boys’ choir because really they were like 30 tough, street guys who sang a little bit out of tune, which I thought was cool, but he didn’t like at all. He wanted an angelic boys’ choir! But ‘The French Lesson’ has a story of boys trying to learn French. I wrote it because I was trying to learn French and write this piece at the same time. And I did it! Well, I didn’t learn French, but I sure wrote the piece of music and it has a lot of French in it, all the important elements for a young learner. I thought the piece would help young boys who are trying to learn French.”

But perhaps this anxiety is simply part of a more ingrained work ethic – more essential to her brilliance than, say, her perfect pitch, which she seems to be getting along just fine without. Her work rate is fast-paced and relentless, but it stops short of being outright workaholic. The workaholic grafts beyond the extent of their capabilities so they don’t have to think about their existence, while it seems like Carla does nothing but work, yet can always consider why she is working: “Even one day without having a piece to work on, I get very anxious. I wonder, ‘What is the [work] worth? What am I worth? What is the point of it all?’ And the answer is, of course, to write another piece!”

Author’s note: due to initial difficulties in communication, this interview was eventually carried out during the summer of 2020 by Steve Swallow acting as my proxy. He asked Carla questions from a lengthy document I wrote for him, and added plenty of questions and insights of his own. Both Steve and Carla were incredibly generous with their time and expertise. I’d like to thank them both for going way beyond what most interview subjects have to put up with.

Thanks are also due for help in sourcing photographs to Karen Mantler and Christian Stolberg.

The book Carla Bley: American Composers by Amy C Beal, published by the University Of Illinois Press, is an excellent source of information about the composer and her practice. And for those looking for suggestions for further listening, Daniel Spicer recently wrote an enjoyable Carla Bley Primer for The Wire issue 444