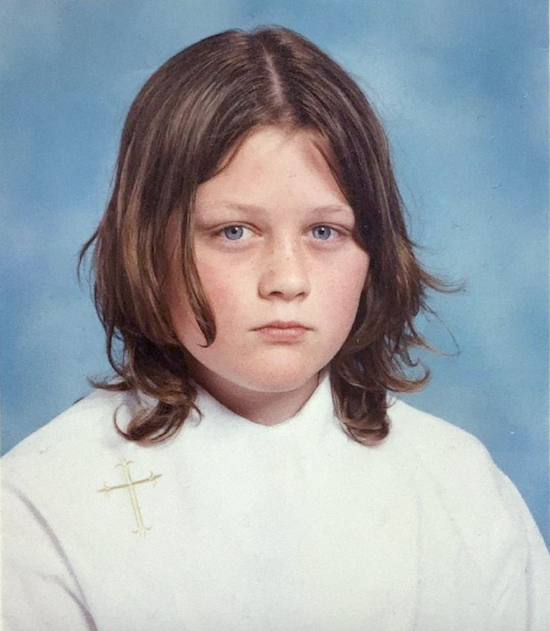

The author, acting as Jesus aged 13, in a school version of Jesus Christ Superstar

“Do you like to shock people, Christian?” says Dr James Fox, perched on the edge of a squat sofa, straight-backed, his neck angled upwards like a dad at a service-station urinal. Just an arm’s length away, Christian Jankowski looks back, smiles, and uncrosses his legs.

It’s September 2016, I feel poorly, and I’m watching a documentary about conceptual art. I’ve no real knowledge on the subject and the film is trying to educate me. It does this in the same language as pretty much any BBC documentary of the past 80 years: polished accents offer informative and dry anecdotes; stock footage brings colour; cameras are slowly approached by presenters who gesticulate and expertly time their arguments to wrap up as they leave the frame. This is a familiar space; a comfortable one. Until the mould is broken.

Fox has interviewed other artists on the show, but this one feels different. Earlier, he was standing in the lift of a Berlin warehouse looking agitated, as a hastily added voiceover filled the room: “I’ve been told to go with the flow.”

Fox knocks on the door and it opens. A middle-aged German man answers – looking something like Tintin on his second marriage – and they shake hands without breaking eye contact. As they turn toward the studio and stroll side by side, Fox makes small talk and compliments the décor, totally ignoring the fact that the artist, Christian Jankowski, is completely naked.

The whole show is brought to a halt. What the fuck is going on? Who is this guy? What are his motivations? “I like to create images,” Jankowski says, as the two sit opposite each other looking like the Sistine Chapel ceiling stuck to an Ikea leather sofa. They begin discussing his art in earnest, the German artist casual and the presenter pretending to be. But this is a standoff, and neither will let up, so the tension builds. What minutes ago was a BBC documentary has now completely transformed, and I don’t know how I feel. Then something else happens which I didn’t expect.

I start smiling. Then I properly start laughing. And the longer both Fox and the documentary itself refuse to acknowledge Jankowski’s naked invasion, the funnier it becomes. This, I realise, is a feeling I understand. I’d mentally prepared to learn about art, but this doesn’t need to be explained. It’s instinctual.

Needing to see more, I searched Jankowski’s name and what was waiting for me was staggering. For people in the know, what had just happened wasn’t completely unexpected. Jankowski, born in Göttingen, now 52, had been creating conceptual art since the early 90s. He’s had solo shows around the world, been featured at multiple Biennales, won the Hamburg Finkenwerder prize for contribution to German contemporary art and been tasked with curating the 2016 Manifesta in Zürich to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Dada. For people not in the know, first co…