"My response to a crisis has always been to create," Nick Cave wrote in The Red Hand files at the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. "This impulse has saved me many times – when things got bad I’d plan a tour, or write a book, or make a record – I’d hide myself in work, and try to stay one step ahead of whatever it was that was pursuing me."

This time, however, things felt different. "It is a time to take a backseat and use this opportunity to reflect on exactly what our function is – what we, as artists, are for," Cave continued. This was written at a stage where we genuinely thought lockdown would last a few weeks, and since then our states of mind have been irreversibly altered. It does beg the question however, what exactly is Carnage for?

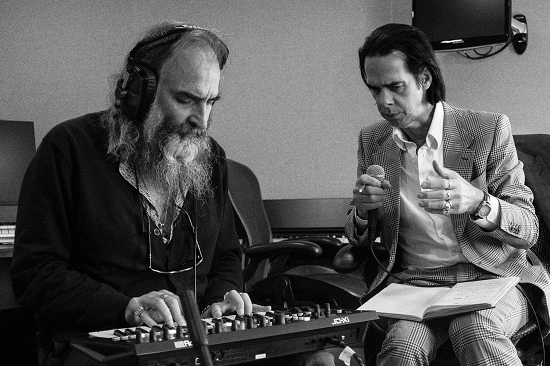

When Cave and his long-time collaborator Warren Ellis met up over lockdown, they did not do so with the direct intention of making a record. Carnage "just fell out of the sky," Cave says in accompanying press material. "It was a gift." Recorded by semi-improvisation, this roaming and unpredictable album sounds like a wild stream of consciousness, a mirror to the intense mood swings and losses of reality that have defined the last year. Though it sounds nothing like it, there are parallels to be drawn with Cave and Ellis’ other non-Bad Seeds project Grinderman, which gained its revitalising power from free-improvisation of words and music.

The bulk of Carnage‘s lyrics were written in the limbo of early lockdown, a period which Cave spent "just sitting on my balcony thinking about things." The most obvious thing to say about them is how closely they reflect the strangeness of our collective state over the last year. They’re constantly shifting in terms of voice and tense, surrealism and simplicity, wandering between reality, memories, daydreams and hallucinations, presented sometimes as a scattergun of disparate images and at others in lingering meditations. Any cohesive narratives that do arrive are fragmentary, wrapped in symbolism and abstraction. Cave’s vocals, which have of late been consistently cracked and fragile, are a whirlwind of different tones, veering from emotive balladeering to wicked snarls to melodramatic croons — a resurrection of the remarkable range of dramatic voices that characterised his early career.

The music strikes a similarly erratic tone. On opener ‘Hand Of God’, an aggressive electronic rhythm pummels in one direction while an opulent swell of strings flies in another. On ‘Balcony Man’, shapeless abstract noises suddenly dissipate to reveal rich, oaky piano chords. ‘White Elephant’, swings manically between extremes. Its first half is perhaps the most outwardly aggressive thing Cave has written since Murder Ballads, on which a menacing figure sits stroking his colonialist weapon, an elephant gun: "I’ll shoot you in the fucking face if you think of coming around here, I’ll shoot you just for fun," he snarls insanely to himself. But then, in an instant, there is a burst of glorious light: "A time is coming, a time is nigh, for the kingdom in the sky!" proclaims a heavenly chorus.

All of this makes for an overwhelming record, one in which it’s impossible to ever feel fully settled, even in its most beautiful moments. At first it feels like a dark rolling mist, a beguiling and shapeless mass of different textures. Over time, however, you begin to notice certain stark and sharply defined images and ideas emerging from that mist for just a moment, only to fade back into the fog. Then, one, three, or seven songs later, you spot that image’s twin, as if all these disparate fragments are reaching across time in conversation with one another.

On the second track, ‘Old Time’, a figure throws their bags into the back of a car, an image that repeats itself exactly on the seventh track ‘Shattered Ground’. On ‘Hand Of God’, "A thing with horns steps back into the trees," and on ‘Carnage’, "A reindeer frozen in the headlights steps back into the woods." On ‘White Elephant’ the narrator imagines themselves to be a melting gun-wielding ice sculpture, which recalls ‘Balcony Man’s "I am two hundred pounds of packed ice, sitting on a chair in the morning sun." On ‘Old Time’, ‘Carnage’, ‘White Elephant’, ‘Shattered Ground’ and ‘Balcony Man’, figures gaze upwards at the sun and the moon. These mirrors can be musical too; the plunging cinematic strings at the start of ‘Hand Of God’ are the same as those on ‘Old Time’, and the ethereal abstract bed on ‘Balcony Man’ matches the one on ‘Carnage’.

Where all the songs across the last three Bad Seeds records, which Cave has described as a trilogy, felt tied together with a strong and burly rope; the threads between the songs on Carnage are like a fragile web, undercutting the notion that music must move from point A to point B. "The idea that we live life in a straight line, like a story, seems to me to be increasingly absurd and, more than anything, a kind of intellectual convenience," Cave said tellingly in a 2017 interview.

From this we can take Carnage‘s labyrinthine, space-time bending structure to be intentional, an accurate reflection of the insane void of lockdown. It’s formally remarkable, although this often comes at the expense of momentum. The thick intensity that Cave and Ellis conjure on the first two tracks is thrilling, but then disappears completely on their glacial follow up ‘Carnage’, never to return. Sometimes the album’s streams of consciousness become so meandering and circular they grow tiresome. The ballad ‘Albuquerque’ is so slow and so ponderous that it almost grinds the entire record to a halt.

But then again, if there’s one thing the last year of stops, starts, U-turns and false dawns has lacked, it’s momentum, and at its core Carnage is a record that reflects 2020. More than anything the pair have ever written, it feels of a particular time and place. On ‘White Elephant’, there is a direct, slightly clunky reference to worldwide protests for racial equality – the year’s other defining socio-political feature. "A protester kneels on the neck of a statue / The statue says I can’t breathe / The protestor says now you know how it feels / And kicks it into the sea."

Photo by Joel Ryan

"I have come to the conclusion that I am essentially a thing that tours. There is a terrible yearning and a feeling of a life being half-lived," Cave wrote in one of his Red Hand Files, in the thick of the third lockdown. It is perhaps no surprise that on almost every song there is a yearning for movement and for travel. There are hallucinatory drives down Lynchian highways, creatures peering from the roadside, and there are blissful wanders through fields of lavender. Parts of ‘Albuquerque’ list one destination after another which he cannot visit.

As the record shifts from one image to another, sometimes it lands on Cave himself, sat on that balcony and writing. On the title track, Cave begins with what seem like evocative images of childhood, a boy watching his uncle behead chickens on a chopping block, but then, he pauses and acknowledges himself. "I’m sitting on the balcony reading Flannery O’Connor with a pencil and a plan." The record ends with the reality of its own artifice laid bare: "I’m the balcony man, where everything is ordinary until it is not," Cave sings on ‘Balcony Man’.

The main success of Ghosteen, the record Cave wrote in the aftermath of his son Arthur’s tragic death and released in 2019, was the way he demonstrated the sheer power of imagination as a way to cope with unimaginable grief. As Cave himself wrote, there are parallels in a pandemic. "I am […] well acquainted with the mechanics of grief — collective grief works in an eerily similar way to personal grief, with its dark confusion, deep uncertainty and loss of control," he said in The Red Hand Files last month.

On Carnage, he and Ellis are once again using their considerable creative abilities as a weapon in the face of tragedy, but this time in the face of something even bigger and more amorphous. "And we won’t get to anywhere, baby / Unless I dream you there," he sings on ‘Albuquerque’.

This, then, is what this music is for. Where in the past, Cave used artistic practice to escape "whatever it was that was pursuing me," on Carnage, he and Warren Ellis confront it head on. The result is a record that sometimes collapses under the weight of that task, but is nonetheless a remarkable demonstration of their artistic power.