When I was 14 I tippexed a quote from Nietzche on my school folder: "One must have chaos within oneself to give birth to a dancing star". I liked the romantic equation the words suggested: great pain = great art. I was a chaotic teenager. I was unhappy. Shit had happened. I wanted it to mean something, for what I had endured to have happened for some greater reason. I was attracted to the idea that it might be a purposeful pain, designed by forces I couldn’t yet comprehend to make me a better writer.

Years later I would get to test this theory in ways I could not have imagined, the result being the 14 songs that make up my new album as The Anchoress, The Art of Losing. In the wake of losing my father, multiple much-wanted pregnancies, and topped off by being given an unexpected cervical cancer diagnosis just days before Christmas, I found myself wanting to further explore the relationship between suffering and creativity. And so I set about interviewing poets, journalists, producers, and songwriters about their experience of making art out of, or in the face of, loss. What I found so remarkable from the ensuing conversations was the unique way in which each grief, each pain, and each sorrow resulted in a different way of navigating loss: Some I spoke to had stopped writing entirely, others couldn’t stop it pouring out. Some found it healing, others sought a necessary distraction from the chaos. What resulted from my conversations was an interrogation of what American poet Elizabeth Bishop called "The Art of Losing"…

I myself couldn’t have planned on writing my second album around the themes of loss and grief. People my age aren’t supposed to watch their dads die of rare inoperable brain tumours. Women like me aren’t supposed to experience more than the statistical average of one in four pregnancies that end in a loss. Someone my age is supposed to be many decades away from thinking about their own death. Songwriters are supposed to write about getting high, falling in and out of love, travelling the world on tour buses, going out dancing, and generally having the time of their lives, aren’t they? But amidst an avalanche of bad luck and wrong turns, I ended the year 2019 with an album recorded that I would never have wanted to write.

And once again, I was that 14-year-old thinking about the Nietzsche quote. I went in search of, as so many before we have, some deeper meaning. I wanted to discover that the unfair allocation of pain meant something.

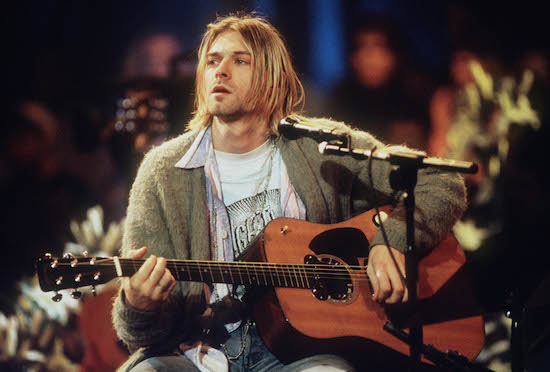

The idea of the tortured artist can be traced as far back as the Greek myth of Philoctetes, the wounded warrior who invented the bow and arrow after being exiled to an island. It’s part of a wider cultural myth that sinking into suffering will somehow, as AL Kennedy has said, "cleanse and elevate the poor and/or unconventional, eventually leading them on to glory." The Hero’s Journey, the myth of Sisyphus endlessly pushing a rock up a hill, Prometheus sentenced to the eternal torment of having his liver pecked at by an eagle: all these classical myths pivot on the essential connection between torment and creation. This pattern is perpetuated in modern culture where we have at our disposal a whole genealogy of literature and music that seems to confirm the uneasy equation: out of pain and death, beautiful bright shadows emerge, the Sylvia Plaths, the Van Goghs, Amy the Winehouses and the Kurt Cobains of this world. Touched With Fire, the psychologist Kay Redfield Jamieson’s 1993 study of the connections between manic depressive illness and the artistic temperament, further cements this suggestion that it is when we are suffering that we create truly "great art".

And yet there is so much to tell us that this isn’t how it has to be. I always cite the wonderful example of Hounds Of Love to counter this weight of cultural evidence of the necessity of sadness – a deep and multifaceted album created when Kate Bush was at her happiest and most productive: "I know there’s a theory that goes around that you must suffer for your art – you know, all that stuff about, ‘It’s not real art unless you suffer’", she said in her 2015 interview with Classic Pop, "But I don’t believe this at all because I think, in some ways, this was the most complete work that I’ve done; in some ways, it’s the best and I was the happiest that I’d been, compared to making other albums."

My own experience of deep grief was as far from Nietzsche’s "dancing star" as I could have imagined as a literature obsessed 14-year-old. It was, instead, a black star of depression, weeping guttural howling, and raging against the unfairness of it all. But still I wanted it to mean something, to somehow have gained out of the unrelenting loss. I was compelled towards the idea that there was some lesson to learn from the multiple losses piling up before me. I just needed to unravel it. And so a seed of an idea was sown that I began to nurture in the process of trying to climb out of grief and simultaneously exploring how we might make something from the losses in our lives: "so what did you learn when life was unkind / and was there some purpose to losing my mind?" the title track of the new album asks.

After some much needed trauma therapy, EMDR, and time-out recuperating, I decided to start talking to others for my podcast (also named "The Art of Losing") about their experiences of loss and trauma and how they made music or wrote books in the midst of, or as a reaction to, loss. We all know the old adage – "when life gives you lemons…make lemonade" and I was keen to discover how those recipes differed: Was there a positive take away amidst the pain? How could we overturn this idea that it was the only way to produce something of note?

But then something strange happened as a result of these conversations: I realised that I was by no means alone in my avalanche of loss. I was not an "unlucky" anomaly but rather I was connected to a huge silent community of normal people going through their own share of human pain and suffering. Friends and acquaintances reached out in private messages to tell me their own stories of miscarriage, illness, and grief. In a parallel timeline, one of my own best friends was now facing her dad’s terminal diagnosis, having also lost her partner and her mum in less than five years. Another talked to me about the death of her daughter and how it had brought her remarkable lifelong friendships in the women she had met that shared her grief. Another lost her baby the week before her due date and bravely posted the beautiful black and white photos they had taken in the hospital room of their sleeping newborn.

The members of the "sad girls club" (as we would come to call ourselves) slowly made themselves more visible and audible to me. "Grief is a world you walk through skinned, unshelled," Ariel Levy writes, and in this new unshelled form I found myself more readily open to conversations with strangers that had shared similar experiences. New friendships formed, new connections were made but most importantly, unexpected lessons were learnt: You cannot master grief – it is not something you can "get over" or win the "battle" with. I was looking for the wrong answer the whole time…

Welsh poet Patrick Jones (brother of Manics’ Nicky Wire) was one of the first people I spoke to about his own "poetry of grief": "We are alone in our grief but connected to others’ grieving and words are the threads stitching us together", he writes in his brilliant collection My Bright Shadow (composed during his mother Irene’s diagnosis of leukaemia). "I never even thought it would be published", he said, writing as a means to document the darkest days of his anticipatory grief. He found himself capturing moments and having to write things down. "I felt I needed to bear witness to her life once the diagnosis was given… so many things to say." Did he feel that he emerged a different person, I asked him? "What do you do with all those wounds? Perhaps you have to build from it a better inner soul…" he summed up. Similarly, songwriter Sophie Daniels (a former hitmaker for Simon Fuller) echoed this sense of having emerged a different person, after the death of her daughter Liberty: "It dropped a bomb not only into my life but also into my relationship with creativity. I know what matters to me now."

Some wrote for themselves. Others found the creative process a way to reconnect with those they had lost. For myself, work was a solace because it provided some structure in a world that otherwise felt devoid of purpose or meaning: the night before my last surgery I frantically typed up mix notes and sent them to my manager at the time Terri Hall, "just in case" things didn’t go well the next day.

In speaking to others, I came to the conclusion that the choice to make art in the midst of loss was not always a choice: the writers I spoke to knew of no other way to process their grief; they wrote in spite of great pain, not because of it. "As a creative, why would you do anything else?" said Daniels, who wrote and released an EP of music about her stillborn daughter last year, entitled Liberty’s Mother. "Some have called me; ‘so brave!’. Others have probably thought to themselves; ‘how foolish’ but as a songwriter, I am neither brave nor foolish, I am simply writing what I want to write." For Sophie, she found the process of making music in the face of loss to be one that helped her to process what she had been through: "I wanted to understand what had happened to me and how I felt about it – a way for me to solve a problem."

The common thread between those I spoke to about making music or writing in the midst of grief was that the art became a tool to make sense of the trauma. It was not made "great" because of the pain but instead became a method to begin to understand what they had been through. The following quote from Proust is splashed across the inside of my album and encapsulates for me the essence of this healing process:

"Ideas come to us as the successors of griefs, and griefs, at the moment they change into ideas, lose some part of their power to injure the heart".

I think that in the process of translating our pain into the "ideas" that are at the heart of any creative process, we can gain a small amount of distance and thus something of the opiate-like quality that making art brings. We simultaneously anaesthetise ourselves while at the same time dulling the ache of what has been lost by reconjuring it again through our words or music. Vocalist Sarah Brown (who has sung with Bryan Ferry, Simple Minds, and Simply Red) echoed this sentiment as she talked me through what she found to be the therapeutic work of singing: "Grief and loss can mute the voice in an emotional sense,” she says; "I could sing but it was ‘sounding brass’ – just making a noise. It wasn’t coming from the true place in me. Once I am able to connect with the grief and not stay in a position of disconnect and I have sung with the pain, you can hit infinity and this allows me to be weightless and not feel the grief. I come out of the other side healed." For Sarah, her creativity was literally muted by her grief – she couldn’t sing – and yet it was also ultimately the means by which she could connect with and heal from it.

For many I spoke to, literature and music also proved a huge solace in that it provided a sense of connection. As Daniels pointed out when her song was able to move a room of MPs to tears: "Sometimes it takes a song to do that". Journalist Kat Lister also spoke to me about the comfort of listening to familiar songs that she had loved after the premature death of her husband Pat Long. She turned to writing to make sense of her young widowhood, the fruits of which resulted in her debut book The Elements (due to be published later this year). "It became a bit of a compulsion for me. I had to find words. I needed to understand. And the way that i could understand was through language," she says. Speaking about devouring the works of Joan Didion, C.S. Lewis, and Carol Joyce Oates, Lister notes that "What all these books have in common is an almost pathological interest in the experience that has consumed them. All of these writers became reporters of their own grief, filing from the frontlines. It helped me to understand this obscene experience in those early days."

This notion of art being a tool with which to make sense of and process loss is one that I also found present in the work of those who weren’t necessarily authoring themselves. I interviewed producer Mario McNulty about what he found to be the "profound" process of remaking David Bowie’s album Never Let Me Down in the aftermath of his death. As a long term collaborator on the Bowie team and personal friend, McNulty talks about the experience as being one that both forced him to confront his own grief but also to celebrate and commune with his memories of the man himself: "You have to sit with loss and think about it constantly over and over so it forces you to confront it as you are trying to do something positive," he says, "You are mourning and you have sadness but you are also looking at all the positive aspects of the relationships". In his role as producer on the project he found himself conjuring up the conversations he had had with Bowie while piecing together the recordings of his voice and instrumental performances. "You can’t avoid it – you are forced to think about the fact that that person is no longer there for you to converse with but yet they are present there in the recordings. This was at times a constant physical reminder of the loss". ForMcNulty this resulted in a "very unique project" that was " a real mindfuck… There is a different resolution at the end of making a record like this. When he was still here it was David who was the one who called the shots. Trying to honour what he wanted was an impossible task".

The act of creation forcing a confrontation with the loss is something that Lister also recalls feeling: "There is something extremely cathartic and magical for me in being able to have a thought and put it down on paper. It’s only when i put it down on the page that I come face to face with some of the thoughts that are percolating". I asked her if she felt as a writer she had a readymade conduit with which to understand the grief she was experiencing as the first piece she wrote after husband Pat’s death was a mere two months after his death. "When I read it back I am quite shocked at what I managed to do," she tells me. "It’s almost like reading somebody else at a point where everything is swirling around. It was my only way of being able to control my own environment. A large part of why I have written about grief is partly to put a narrative out there that others will connect with but equally important to understand what is happening in me."

As Lister notes, the experience of your loss can be very specific to you but at the same time it can resonate universally with other people. For Daniels also, her original intention with the Liberty’s Monther project had not been to make this wider connection with others but to work through her own feelings about the death of her daughter: "I didn’t write it intending to share it with the world in this way", she says of the song that became part of a campaign for the charity Tommy’s last year.

For me, the myth of "great art" arising out of suffering is a damaging notion perpetuated by the books that we love and the records we cling to in our adolescence. We grow up hearing how "love hurts", studying plays that romanticise a double suicide of two "star-crossed lovers", and mythologizing the 27 club of rock stars that died too soon, or great artists of genius that painted masterpieces before ending their own lives. It’s no wonder the trope of the suffering artist is so deeply ingrained in both our minds and our culture. BuI I have come to know it as a tired trope trotted out only by those who have been fortunate enough to not yet have experienced their own personal chaos. I don’t recognise this myth of bright-burning creativity in my own tale of losses and darkness. On the contrary, in the midst of the hell of the past few years I was almost certainly not at my most creative, oftentimes unable to get out of bed, paralysed by deep grief (and what I would later find out was something called "complex PTSD"). On my better days I would force myself to get up and work, just to fill the void of the day. I would hide my swollen and hemorrhaging body from those around me and find small comfort in the repetitive task of track editing or problem-solving a string arrangement.

I have always thought there was something essentially death-defying in the very act of writing. As artists we are refusing always mortality – the very act of creating is a circumnavigation of death in the act of committing the words to the page that, with any luck, might exist long beyond our own human shells. But art is made in spite of great pain, not because of it. Even if it provides a much needed salve in the darkest of times, it is dangerous both if we pursue it and if we romanticise it.

Rather than chase down the "chaos" of our adolescent "dancing stars", under the illusion that it might make us burn brighter, write better, I’ve come to learn that we should instead acknowledge those deep scars that they leave upon the body of our lives so that we can in time turn our gaze once more towards the light. Because, to paraphrase Leonard Cohen: "that’s where the light gets in".

Catherine Anne Davies makes music as The Anchoress. The second album, The Art of Losing, is out 12th March 2021, for more information visit The Anchoress website