In the febrile week before the national lockdown was imposed, booksellers were flummoxed by a sudden surge of requests for copies of Dean Koontz’s novel, The Eyes of Darkness. On social media, it was being shared as an unlikely prophetic text, describing a virus being concocted in a lab outside the city of Wuhan as a biological weapon. As the pandemic was wreaking unprecedented tumult across the world, people desperately grasped for a narrative to make sense of their historical dislocation and found it in a horror novel from the eighties.

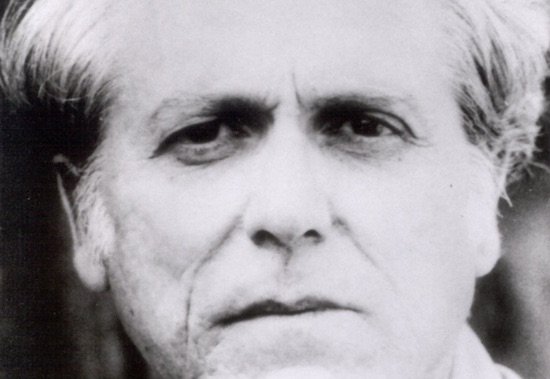

Those heady days of mystical end times revelation have since curdled into anti-mask protests and deranged QAnon conspiracies but the literary world’s prophet-in-chief, Don DeLillo, has made an auspicious return with The Silence. The novel, according to the blustering marketese accompanying the book trade proofs, has “echoes of the sudden, isolating effects caused by Coronavirus.” On the evening of the Superbowl 2022, a small party is convening in a Manhattan apartment to watch it, but just as the game is about to kick off, the screen goes blank. The phones are down. Theories abound in the block: “Something technical … A systems failure. Also a sunspot.” What happens when the gossamer threads of connection are severed so suddenly?

This is the apocalypse that is imagined in DeLillo’s eighteenth novel, one that’s impact would be even more devastating as so much of our lives has migrated onto the digital realm. It does not much resemble our current predicament but to judge a novel set in the future by the accuracy of its predictions has always been an irrelevant criterion. We do not continue to read Philip K. Dick because we’re now all wearing scramble suits and tending artificial pets but for the still resonant ontological implications of a reality that has been absorbed into the authoritarian dreamworlds of corporations. DeLillo’s work may not employ the generic armature of science fiction like Dick but it is shaped by the same paranoia and anxieties about the trajectory of modernity that has become increasingly estranged from the human.

Jim and Tessa are flying to the party from Paris. On the plane “much of what the couple said to each other seemed to be a function of some automated process, remarks generated by the nature of airline travel itself.” Human interaction has been hollowed out into rituals dictated by the commercial spaces they take place in. DeLillo’s dialogue has never aspired to naturalism in any case, always vacillating between the gnomic and the banal.

Much of their conversation is pre-occupied with language itself, mulling over peculiar words. This has become something of a hallmark of DeLillo’s late style. His novels from this century have become more condensed, rarely breaching the two hundred page mark, this one being no exception. Words are more carefully chosen and take on numinous qualities. In his over 800 page opus Underworld, Nick Shay confesses to his obsession with The Cloud of Unknowing, a medieval work of Christian mysticism, which he explains counsels that the best way to approach knowledge of God is to fixate on a single word. Its anonymous author says that “with this word you will hammer the cloud and the darkness above you.” Of course today the cloud is the ethereal vessel that houses our collective digital memory. In The Silence, the cloud has evaporated and everyone is left with only their words.

When the systems go down, retired physics professor Diane and her husband Max are waiting expectantly for the match to begin along with Diane’s former student, Martin, and suddenly find themselves anxiously having to fill the silence. As Max goes to investigate the cause, Martin starts quoting from his sacred text, Einstein’s 1912 Manuscript on the Special Theory of Relativity. “He said it and then we saw it … His universe became ours,” he remarks, casting Einstein as a hierophant of a secular theology. Theoretical physics doesn’t really provide the narrative shape that prophecies normally offer but black holes and event horizons give the text its obligatory apocalyptic hue. After returning from his investigations, Max sits himself in front of the superscreen, bourbon in hand and becomes an antenna receiving the game, broadcasting the commentary and adverts in an incantatory echolalia. In DeLillo’s fictions, these religious impulses have a habit of piercing through the bland carapace of sterile tech-mediated existence, characters straining fruitlessly towards the divine.

The affect of dread that permeates the novel is not isolated to the network outage. The flight carrying Jim and Tessa comes into turbulence. Its crash landing is elided from the text only adding to a structural unease. It becomes emblematic of the eschatological imaginary, those apocalyptic thoughts that burble just beneath the surface of consciousness. “It was always at the edge of our perception,” Tessa ruminates aloud before preaching a biblical litany of disasters, including a reference to coronavirus, and asking, “Are we an experiment that happens to be falling apart, a scheme set in motion by forces outside our reckoning?”

It is a question that was just as applicable when much of the world was in enforced isolation earlier this year. Despite its nod to the current crisis, The Silence feels like it is a transmission from a world dated BC – Before Covid. The texture of the collective anxieties about the fragility of our digital lives is somehow both resonant and distant. When Max walks out to join the crowds bewildered by the power cut on the streets of Manhattan, it is hard not to recoil from the lack of social distancing. This is the parallel universe in which the pandemic never took place but one that holds truths for our own.

Back in the apartment, everyone takes it in turns to erupt into a Beckettian monologue, each in a ceaseless torrent articulating their inability to articulate their ideas because, as Max observes, “the current situation tells us that there is nothing else to say except what comes into our heads, which none of us will remember anyway.” Like many of us during these last few months, he once again stares at the screen vacantly, waiting for a revelation that never seems to arrive.

The Silence by Don DeLillo is published by Pan Macmillan