It feels like Lawrence Lek has finally taken the seat that has been patiently reserved for him by Hyperdub, and frankly, the timing couldn’t be more perfect. The label has harboured a long time fascination with the ideas that his latest CGI film AIDOL revolves around, namely, western perceptions of Chinese culture and science fiction’s relationship to electronic music. From Fatima Al Qadiri’s Asiatisch LP to Kode9’s ‘Xingfu Lu’ single named after the Shanghai street where it was made, you can find traces of their Sino fascination peppered throughout the imprint.

When it comes to sci-fi, their creative manifesto was laid down in the ominous soundscape and narrative of Kode9 and The Spaceape’s 2006 collaboration, Memories of the Future. Spinning kaleidoscopic threads on all things esoteric, astral and alien, In ‘Portal’, Spaceape talks of being “Guided by subliminals that’s from another galaxy” and in ‘Victims’ he imagines alien viruses being spread by “Creatures covered, smothered in writhing tentacles.” It’s in the first single ‘Glass’, that Hyperdub’s statement of intent is made clear when Spaceape incantates, “Through science, we find alliance to endure reality, creating blinding lights of fiction as our only clarity.” While the “science” and “fiction” part of that line are apart, thematically they sit snugly next to each other. From Brian Eno’s ‘Prophecy Theme’ for Dune to Vangelis’s seminal Blade Runner OST, electronica has a rich history as an accompaniment to sci-fi films; the difference in Hyperdub’s approach is in not using electronic music as a complement to world building, but as the canvas in which the vision is brought to life.

It helps that the synthesized sounds of electronica naturally lean toward futuristic notions of a machine world, or at the very least, the first step towards it. In AIDOL, Lawrence Lek has expanded on that concept: now machines don’t only make the music, but write the songs, and perform the music themselves. While Lek hasn’t explicitly created a world solely within the framework of an LP, the symbiosis of the music and the film’s narrative is on its way to the realisation of the promises Spaceape uttered in ‘Glass’. Musically the two records couldn’t be further apart, but conceptually there is a clear lineage, with AIDOL representing a significant milestone in the label’s vision to marry science fiction and electronic music that was started in Memories of the Future.

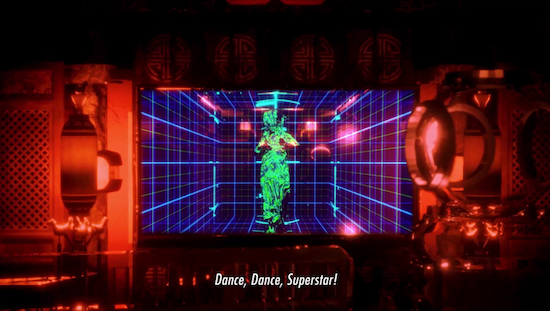

Performed in English and Mandarin and set in China in 2065, the project is centred around Diva, a singer that is fighting the slow fade into obscurity by hiring an AI songwriter to help make a comeback at the eSports final (a video-gaming competition which is essentially the Olympics of the future). The film itself is split into segments, mirrored by the track list of the soundtrack, with each song reflecting a stage in Diva’s journey for acclaim and creative autonomy in an entertainment industry driven by predictive cycles and algorithms that serve instant satisfaction to the masses. A world where individuality has become nothing more than a computer-generated illusion.

Like all good science fiction plots, AIDOL is also a covert essay that wrestles with multiple tangents and ideas. In Diva herself there is a commentary on the superficiality and allure of fame. Running alongside her arc is a commentary on contemporary Chinese culture. Those discourses are condensed under the umbrella term ‘Sinofuturism’ which is based on the stereotypes of computing, copying, gaming, addiction, studying, labour, and gambling. Lek flips the negative connotations of those cultural cliches, until they end up empowering the machine they could have easily brought down, in turn facilitating China’s progress to technological juggernaut through the story’s mega corporation, Farsight. Lek’s choice of setting is made even more relevant when taking into account that China are on their way to becoming the leading AI superpower. According to tech pioneer Kai-Fu Lee, "If data is the new oil, then China is the new Saudi Arabia.” In AIDOL, Lek places China as the nexus of the hypothetical singularity. As the gateway to an intelligence explosion that once happens, cannot be contained, controlled, or reversed.

The work taps into current anxieties in regard to the digitisation of culture, the outsourcing of mental capacity to our devices and humanity’s general reliance on technology. In Lek’s world those tensions have been muffled by the smoke and mirrors of the AI, the difference between his “2065” universe and the typical apocalyptic AI scenario is that his machines haven’t destroyed human culture but appropriated it into its own twisted parody. Gaming becomes the proxy battleground of that world, in which humans and AIs (or “bios” and “synths”) battle for supremacy on multiple levels.

The true ambitions of the AI are kept literally underground throughout the film, revealed to returning character Geomancer through the sub plot that runs parallel to Diva’s journey. Secrets like AI purposefully losing in chess tournaments to maintain the illusion of balance between man and machine. This game of cat and mouse is covertly encapsulated in Farsight’s ironic tagline “aligning AI with human interests.” Whether humans have aligned AI to their interests, or the AI have aligned humanity to their interests is one of the big questions the piece discusses and is ultimately left for the audience to decide.

The nuanced power balances of Lek’s world are masterfully communicated in the film’s philosophical dialogue but also projected into the musicality of the soundtrack itself. In the opening track, the humming of Diva over rainforest sounds paints the picture of a Chinese princess cleaning her hair in the river, but once she starts singing the image is shattered by her sterile vocoded voice. This artificiality is a key motif of the soundtrack, multidimensional in regard to both the ambiguous nature of Diva’s true identity and the artificiality of manufactured pop music. A shot to the managers, songwriters, and marketers who create and push faux icons. The tension between “bios” and “synths”, or nature and technology, starts from the very beginning of the record, in the dissonance and distance between the synthetic voice of Diva and the natural rhythms of the forest. She immediately feels like a displaced presence, a stranger wandering the void searching for meaning through the validation of the audience. It’s all ultimately a futile undertaking. Farsight eventually informing her that, “Nobody cares about your story, only theirs.”

‘Deep Blue Monday’ continues the theme and highlights both Diva’s identity crisis and longing for creative freedom, with the lyrics “No life to live, no time to shine / No voice to sing, no voice to tell stories of mine.” In ‘Chance Encounter (Jungle Theme)’ Lek uses zen flute sounds to evoke images of swaying bamboo and Chinese pastoral beauty, as digitised droplets patter the background and irrigate the aural landscape. It’s a breath of fresh air from Diva’s, at times, overbearing lament, and hints at a natural world sandwiched and suffocated in between the vice-grip of human corporations and synthetic egos. Diva’s warbling notes on ‘Call of Beauty’ (a nod to the video game franchise, Call of Duty) struggle to unearth emotion in herself – as well as the audience – as the neon waveforms of the production feel like they are similarly oscillating in emulation of natural patterns. In ‘Welcome to SoMA’ we are introduced to the god-machine embedded in the texture of the music, the sounds of malfunctioning electronics simulating the overloaded processes of quantifying mass data.

Lek’s grinding, mechanical production on ‘One Nation’ delves into the dark, industrial underbelly of the “2065” reality. Diva’s vocals that creep in and out, in contrast to the clarity of previous track ‘Superstar’, now sound fractured and glitchy, like a disembodied consciousness whose sentience is slowly being smothered by oceans of code. The use of the Chinese language in tracks like ‘In the Game’ and ‘Beware your fans, Diva’ feels like a specific musical choice too, the distinctive Mandarin phonetics creating a greater sense of removal and otherworldliness for a Western audience. The English lyrics often juxtapose the music itself – sad lyrics with upbeat instrumentals and vice versa. The result is ultimately an ambiguity as to what emotion you are supposed to be feeling.

While the film definitely informs and enriches the soundtrack, it is not essential viewing. The press release is enough to immerse you into Lek’s idiosyncratic world, and in some ways going in blind is an even more interesting way of experiencing it. Either way, AIDOL represents the culmination of Lek’s world-building, a space in which the dots established in previous films, Sinofuturism (1834-2046 AD) and Geomancer have all been connected and formed into one cohesive whole. After Covid-19 and Trump’s diatribes against China, the rise of commercial AI with Siri, and the explosion of viral Tik-Tok fame, AIDOL and its explorations into fame and otherness couldn’t have come at a better time. Diva’s manager speaks directly to the moment when he sums up the expendable and ultimately disposable nature of fame, technology, and power with the phrase, “First they need you, then they’ll delete you.”