The metaphor of the LP record as a "canvas" has a far older vintage than the recent trend for shops selling 12" square frames and stats suggesting half the new vinyl bought will be never touch a turntable. The album was always a medium of display – the very word itself derives form photo albums and the first music ‘albums’ were luxuriously bound books in which to store your (already purchased) shellac discs.

Contemporary artists have long been fascinated by records. Whether it’s the likes of Milan Knížák, Nam June Paik, or Christian Marclay incorporating other people’s – often broken – records in visual artworks, or avant-gardists like Joseph Beuys, Jean Tinguely, and Braco Dimitrijević releasing platters of their own, vinyl has clearly made its mark on contemporary art beyond emulsion paints and the fetish wear of Monica Bonvicini.

In the 1970s, Italian curator Germano Celant gathered many artists record works together in an exhibition for the Fort Worth Art Museum in Texas entitled The Record as Artwork: From Futurism to Conceptual Art. The record, Celant explained in the accompanying book, "enriches the array of linguistic tools available for the task of exploding the specifically visual, and pushign back the limits of the art process." But for many visual artists, designing record sleeves was not so much a means of exploding the specifically visual as simply a way of earning a living.

The following – far from exhaustive list – gathers record sleeves by twentieth century artists, sometimes as artistic statements in their own rights and sometimes simply as a paying gig. Some follow the general style of the work the artist in question is known for, and others depart from that style (or styles) in interesting ways.

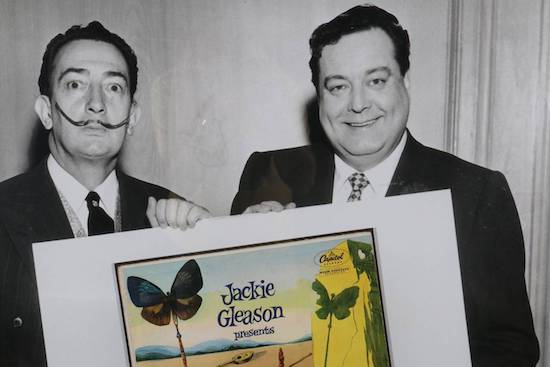

Jackie Gleason – Lonesome Echo (Salvador Dali, 1955)

The eminent surrealist and the Smokey and the Bandit actor were a pair of unlikely buddies, gadding about 1950s Hollywood, when the latter asked the former to design a record sleeve for his mood music side gig. Dali was only too happy to oblige, providing sleevenotes for the record to boot. "The first effect," he wrote in typicaly elliptical fashion, "is that of anguish, of space, and of solitude. Secondly, the fragility of the wings of a butterfly, projecting long shadows of the late afternoon, reverberates in the landscape like an echo. The feminine element, distant and isolated, forms a perfect triangle with the musical instrument and it’s other echo, the shell."

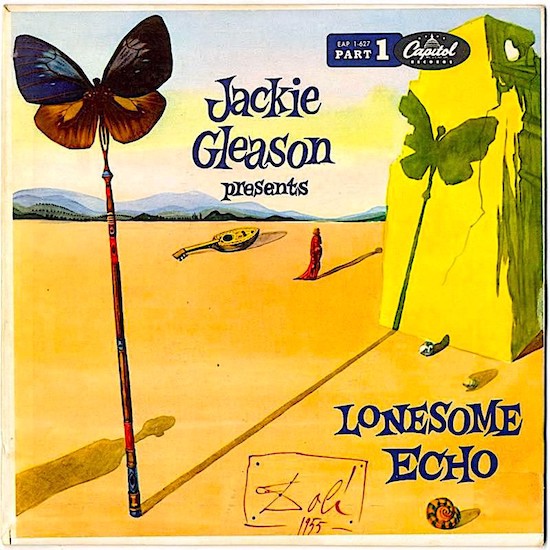

Terry Snyder & The All-Stars, Persuasive Percussion (Josef Albers, 1959)

In 1959, former Bauhaus professor Josef Albers had just left a teaching job at Yale when he was called up by a former student, Charles E. Murphy. Murphy had been made art director at Command Records, a new label run by lounge music bandleader Enoch Light, and was looking for something abstract, modern, and eyecatching to go on the sleeve of a series of percussion records by Light and drummer Terry Snyder. The results can be seen on three volumes of Provocative Percussion and two of Persuasive Percussion (volumes 1 and 3 – Murphy handled design duties on Persuasive Percussion volume 2 himself), representing practically the only commercial art work in Albers’ career. A 2015 article about the collaboration in The Atlantic, quotes Herb Lubalin Study Center director Alexander Tochilovsky, "The use of squares, and of grids of dots are consistent with [Albers’] modernist pursuit of the simplest and most effective means of communicating the intended subject, and with his interest in interactions … The dots break off the grid and bounce up in an elegant way that alludes to the music’s dynamic range and of the stereophonic ‘bouncing’ occurring in the recordings.”

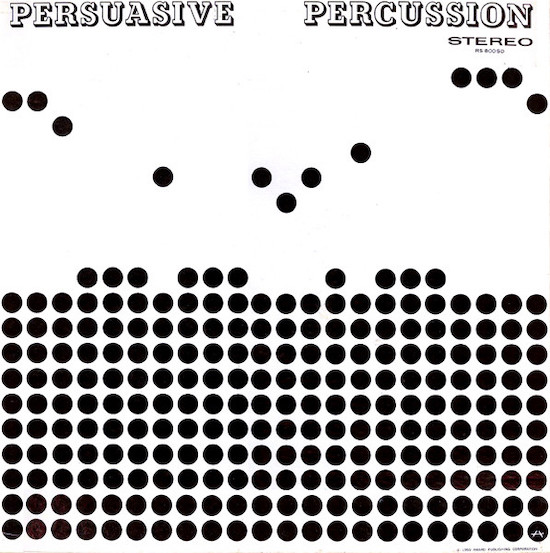

Elaine Brown, Seize the Time (Emory Douglas, 1969)

From 1967 until 1982, Emory Douglas was the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, in which capacity he was responsible for a lot of the group’s graphic branding as well as the design of The Black Panther newspaper. "Revolutionary art," he wrote in one edition of that journal, "begins with the program that Huey P. Newton instituted with the Black Panther Party. Revolutionary art, like the Party, is for the whole community and deals with all its problems. It gives the people the correct picture of our struggle whereas the revolutionary ideology gives the people the correct political understanding of our struggle." Seize the Time was the first album by another Panther member, Elaine Brown, an album of jazzy agitprop with an unmistakable front sleeve.

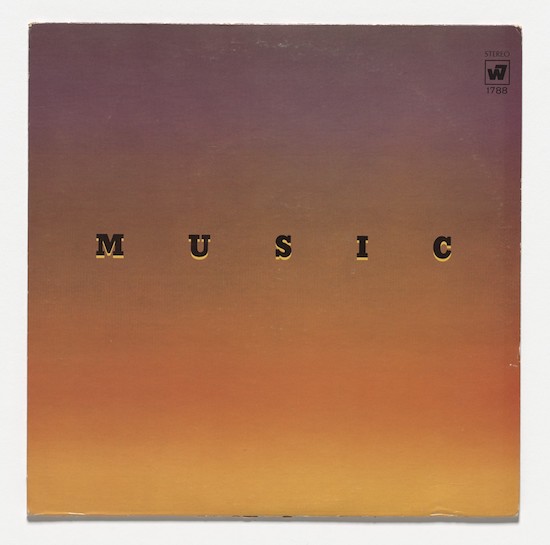

Mason Williams, Music (Ed Ruscha, 1969)

Singer-songwriter Mason Williams had been friends with Ed Ruscha since they were both kids back in Oklahoma City. Williams composed music for the Smothers Brothers and Saturday Night Live while Ruscha was quietly transforming the lexicon of contemporary art, taking his leads from Jasper Johns, Edward Hopper, and Marcel Duchamp to create a new kind of cool minimalism with the prefab landscape of suburban America at its very heart. Williams and Ruscha collaborated on numerous projects throughout their lifetime, from chance-determined photo-stories to an attempt at making a film in which an old bi-wing aeroplane draws a flower in the sky with its vapour trail. Perhaps surprisingly, this is the only one of Williams’ record sleeves that Ruscha put his hand to.

Cream, Best Of… (Jim Dine, 1969)

Judging by the comments online, pop artist Jim Dine’s sleeve for this Cream greatest hits collection didn’t go down too well with the band’s fans. "That black-and-white sketch of the cucumbers isn’t even finished (besides looking a bit phallic)," complains one guy on a forum. But Dine’s sleeve continues the artist’s attempt to defamiliarise the most mundane and recognisable of household items, treating aubergines and oranges as abstract forms much as an earlier generation would have employed purple and, well, orange. A participant in the important New Painting of Common Objects exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1962, alongside Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and Ed Ruscha, Dine remains a unique voice in contemporary art, with a show of new works currently on view at Galerie Templon, Paris.

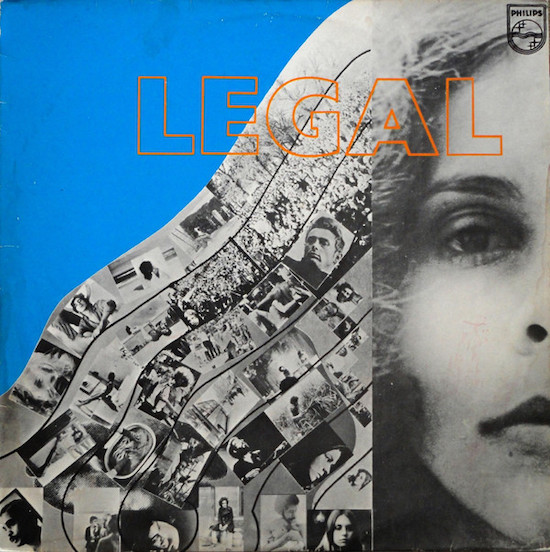

Gal Costa, Legal (Hélio Oiticica, 1970)

Hélio Oiticica coined the word ‘Tropicalia’ for the name of an installation – all raked sand, potted palms and loose floral fabrics – in 1967. It later became the name of a song (by Caetano Veloso), a compilation album (featuring Veloso, Gal Costa, plus Tom Zé, Os Mutantes, and Gilberto Gil), and a whole aesthetic movement, spanning music, theatre, poetry, film, and visual art. But by the end of the 60s, the movement was in disarray, its two principal figureheads – Veloso and Gil – in exile following two months imprisonment. Legal, Costa’s third solo album, features songs written by both of them, and others associated with the movement. Oiticica’s redraws Costa’s hair as a photo stream or film strips, bearing images of several of her collaborators, like a surge of memories flowing from her brain.

Philip Glass, Music in Twelve Parts, Parts 1 & 2 (Sol Lewitt, 1976)

Sol Lewitt used to say that he did his best work sitting in the back of Philip Glass rehearsals. It’s not hard to find parallels between the repetitive, modular patterns in the music of Glass and the sculptures of Lewitt and the latter spoke often of the influence of music on his work. Both were dubbed ‘minimalists’, though neither were always happy with the term, and both had a connection to Paula Cooper’s Park Place gallery, where several key works of minimalist music were first performed. Lewitt was famous for his extensive music collection and he owned several of Glass’s original scores. "Sol called me up and said, ‘Can I buy a score?’" Glass recalled years later. "I couldn’t believe it. He bought basically all the scores I wrote for three years.… Whatever he had, he shared with other people."

Love of Life Orchestra, Geneva (Lawrence Weiner, 1980)

In his book, Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, Tim Lawrence describes the Love of Life Orchestra as "a kind of downtown big band" which at one time featured Russell, Laurie Anderson, Kathy Acker, Peter Zummo, Jill Kroeson, and "Blue" Gene Tyranny, along with half the regular crowd at the Kitchen. Fusing minimalist new music with disco beatrs, LOLO was "as much a political statement as a musical one," according to its founder Peter Gordon. "I was looking to create an ensemble in which musicians from a wide range of backgrounds could flourish – a democratisation of style." The sleeve for the groups’s debut album Geneva was far from Weiner’s only involvement in music – he made several albums with Ned Sublette in the 90s and even produced an opera with Peter Gordon. But the graphic style and typeface employed here do mark this out as one of the most obviously Weiner-ish of Weiner’s musical interventions.

Diana Ross, Silk Electric (Andy Warhol, 1982)

Everybody knows Warhol’s famous sleeves for the Velvet Underground and the Rolling Stones from the 1960s. Before becoming the poster boy for Pop Art, Warhol had also illustrated several albums of jazz and classical music in his line of work as a commercial artist – some of which now sell for hundreds on Discogs, despite the anonymity of Warhol’s cnotribution. The story of his collaboration with Diana Ross starts with her appearance on the front cover of Warhol’s Interview magazine in 1976. Later, the singer comissioned Warhol to paint not only her own portrait but also that of her three daughters. "Diana Ross came at 3:00 and she loved all the portraits," wrote Warhol in his diary, "she said, ‘Wrap them up,’ and they all fit in the limousine, and she had a check at Bob’s place by 5:00. And she wants me to do the cover for her next album."

Rammellzee vs. K-Rob, Beat Bop (Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1983)

Basquiat did more than just design the sleeve for this seminal slice of New York hip hop. He paid for the recording, produced the record, and was – apparently – all set to spit his own verses until Rammellzee and K-Rob read his intended verses and laughed him out of the vocal booth. Rammellzee himself would subsequently dismiss the track as "just having fun", but its stream-of-consciousness verses and expressionist use of effects continues to garner praise, regardless, with blogger Woebot praising it as "both hip hop’s artiest and its rootsiest record" in his list of the 100 Greatest Records Ever in 2005.