All the conditions have been met for Cabaret Voltaire’s return now that the dystopian future we were promised is upon us. A first album in 26 years comes with one sole survivor at the helm. Chris Watson left the band in 1981 to become a Tyne Tees soundman, and Stephen Mallinder departed in 1994 in order to plough his own furrow. Now, following an interregnum that spans a generation, Richard H. Kirk has decided to continue alone under the moniker he’s best known by.

Despite the fanfare, Shadow of Fear isn’t technically the first output from Cabaret Voltaire since The Conversation. Kirk remixed Kora in 2009, and revived the name for a lowkey collaboration with the Tivoli, though it was apparently a festival appearance in 2014 under the appellation that really reignited the idea of a reformation of one. The Cabs move in mysterious ways, though according to their own manifesto, they only move in one direction… inexorably forward. “I just don’t like the idea of retreading old ground,” Kirk told biographer Mick Fish back in 1983, “and that is why we try to keep moving on all the time.” No nostalgia has always been the mission statement, and Kirk apparently prefers not to talk about former glories in interviews. “It’s nice that people appreciate what you’ve done in the past,” he said more recently, “but it’s a dangerous place to dwell.”

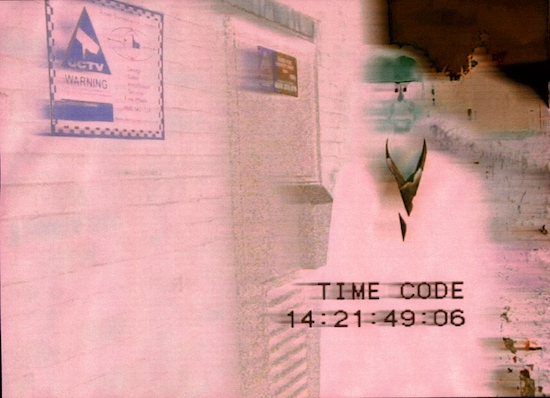

And therein lies the paradox of Shadow of Fear. It is brand new music, and yet every second is haunted by the sonic signifiers of the past. Following a software failure and an aborted attempt to update to digital, Kirk returned to the analogue equipment of yore and everything seemed to fit perfectly again. The method remains the same, with tracks like ‘Be Free’ and ‘Night of the Jackal’ building samples and atmospherics upon the foundations of an old drum machine pattern. Side A is full of lopsided, unnerving music featuring a distorted, virilized voice barking out barely audible slogans like “this city is falling apart”, adding to a sense of alienation. It’s the musical equivalent of a particularly foreboding Michael Haneke film, with the same troubling themes of disturbance, paranoia, detachment and a preoccupation with surveillance, all cut and pasted over an 808.

There are references in the work that are never explicit. ‘Night of the Jackal’ is perhaps one of the more obvious ones. ‘The Power (Of Their Knowledge)’ presumably tips a chapeau to Foucault. Whether or not there’s been an epistemic shift since the founding members and their coterie were coming home drunk from the pub and experimenting with patched up magnetic tape is not something I’m qualified to comment upon, but there’s certainly a sense that we’ve come full circle socially and economically and the ennui of forty years ago is upon us again.

Mick Fish’s book Industrial Evolution: Through the Eighties with Cabaret Voltaire is an odd hotchpotch of his experiences following the band when his appetite for Throbbing Gristle wanes, juxtaposed against the sisyphean drudgery of working for the council and the steady descent into alcoholism that comes with trying to escape the mundanity of existence. If you can get past the author’s homophobia in the intro, it’s a fascinating social document of postwar Britain with a backdrop of pubs, grubby basements, fuliginous skies, brutalist warehouses and bedsits, and entertainment so thin on the ground that you either make something to alleviate the boredom or you call your speed dealer.

Bleakness permeates Kirk’s music now just as it permeated ‘Nag Nag Nag’. Side one exemplifies 2020 in that it’s not entirely successful. While there are great ideas bursting to get out, it also lurches mechanically and is difficult to love. It often feels laboured, like Kirk is giving himself a migraine trying to reinvent something because you suspect he feels that’s his job. Flip the record over and the outlook changes. Once he submits to the pulsating rhythms and allows himself to be free then there’s a gold rush. ‘Universal Energy’ is banging, soaraway techno and ‘Vasto’ too is pulverising, fucked up dance music. Whether or not any of it is groundbreaking is really immaterial. Richard H. Kirk has more than contributed to the rich fabric of our culture and warrants this victory lap calling himself anything he wants to.

Cabaret Voltaire – alienated synthesists (as Phil Oakey would have it) – invented ideas from the peripheries, untrammelled by the conformity of the mainstream, except when they did try to have some hits themselves and discovered they were too idiosyncratic for popular tastes (M|A|R|R|S jumped into their slipstream somehow and had the weird, massive chart topper). It shouldn’t have to be stated that it’s not necessary to be prescient and innovative all the time, and if you’re raising a plucked eyebrow then expectations have been set too high, which is only to be expected when a quarter of a century has passed. There’s a received wisdom that Cabaret Voltaire have always been the bridesmaid, but from anecdotal evidence and observing with my own eyes, being a bridesmaid looks to be a wholly entertaining and fulfilling obligation.

Perhaps most amusing of all is the fact that while Richard H. Kirk is using the Cabaret Voltaire name again, he never went away. The albums made under a variety of pseudonyms are legion. Search Google or Discogs or your streaming app of choice and you’ll find seemingly endless reams of quietly seditious techno under a plethora of aliases: Sandoz, Electronic Eye, Al Jabr, Biochemical Dread, Blacworld, Sweet Exorcist, Vasco de Mento, and so on, as well as under his own name. When I pitched this article I had the idea to farm as much of this sonic landscape as possible, in direct opposition to Kirk’s need to keep moving forward, though it turns out his collective works are unfarmable and he is like a skint aristocrat in a tatterdemalion mansion looking out over vast acres of untamable verdure.

There really is so much of it that all you can do is dive in and take a little bit of what you need. Except for maybe a small hardcore, it seems impossible to catalogue everything, though there are worse things you could do with the Richard H. Kirk discography in all its incarnations than work inexorably backwards. Personal favourites I’ve come across include the ethnotechno electronica of Sandoz’s 1993 album Dark Continent, the early 2000s Electronic Eye albums that aren’t that dissimilar to the new Cabaret Voltaire record, and 1987’s Hoodoo Talk recorded with the Box’s Peter Hope, which mines a similar industrial rock to the concomitant Nitzer Ebb on tracks like ‘Leather Hands’.

The harvest is there for the taking and you should feel no shame looking to the past for inspiration. “Dada is not modern at all,” said the movement’s gospel writer, Tristian Tzara. “It is rather a return to a quasi-Buddhist religion of indifference.” If much of what Cabaret Voltaire did was in the spirit of the Dada, then in a sense, they won. Dada and cut-up culture is all around us now. And as everyone knows, the least interesting thing about Dada is the name itself.