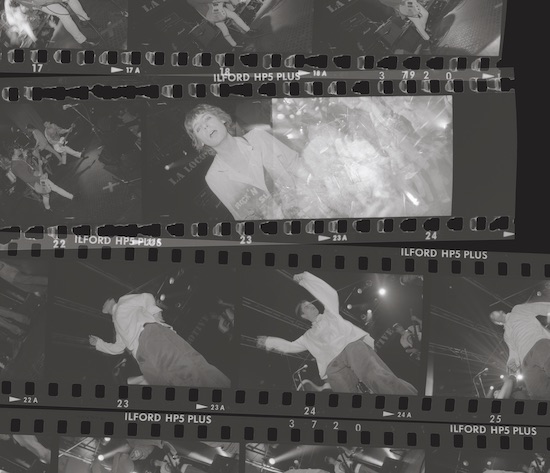

All images by Steve Gullick

As much a code of conduct as a band, Flowered Up were an unnatural high. A weed that grew through the pavement cracks of a north London council estate and transformed into the original

full-petal racket, they went from club faces to cover stars and into total chaos within two short

years. The five-headed embodiment of a postacid-house club culture that had rewired brains the country over, Flowered Up were Heavenly’s first bona fide ‘band’. They also provided the nascent label with one of the first real lessons in how the industry worked: if you get enough people rabidly excited by something, someone with a bigger wallet is inevitably going to come and try to buy it off you.

After two killer 45s for Heavenly (‘It’s On’ and ‘Phobia’) the band were poached by London Records for a deal rumoured to be worth in the region of six million pounds. Unfortunately, it took a while for the band to realise that the money wasn’t all theirs. After one overproduced, underwhelming album and a drug-fuelled spending spree, the relationship with the label had soured. The delivery of an uneditable, twelve minute-long single that somehow managed to perfectly encapsulate the anticipation, execution and aftermath of a night out was the final straw. The band returned to Heavenly with that track, ‘Weekender’, their glorious, immortal swan song. Robin Turner

DES PENNEY, Flowered Up manager

From the start of 1988, me and Liam [Maher, Flowered Up singer] were going out every night of the week. For a stretch of two solid years there wasn’t a night that I wasn’t out in London. Pilled-up every fucking night, lapping it up, living it and loving it. Acid house quickly encouraged

people’s desire to push and experiment. People wanted explore the opportunities that were clearly unfolding. More than just a music scene, there was a whole new economy emerging, one that provided a completely fresh starting point for a lot of people. All of a sudden the despair and monotony of the eighties fell away. Even if your life wasn’t radically changed, the pills provided a colourful backdrop that made life more bearable. Before acid house happened, I liked to go and see live bands. That was what drew me to places like the upstairs at Spectrum. There, people like Terry Farley and Pete Heller and Roger the Hippie played the music that was becoming known as Balearic. The music was a lot more diverse than in the main room, lots of different influences falling together. People obviously came to clubbing from different backgrounds – you’d party with mods, people from the soul scene, people who’d liked heavy rock. Everyone had come together in front of the speakers but people’s previous musical tastes mostly remained intact; yet they were a lot more accepting of differences, not so uniform.

After a while, the parties started to wane. They were becoming repetitive and you started to get all this DJ worship going on. I wasn’t into it. DJs had been an extension of the music and the dancefloor but as things got bigger, lots of people’s egos were growing, whether they were playing records or putting on clubs. It felt like something else needed to happen. The buzz was fading and all the real fun seemed to be happening afterwards. Everyone was making new friends, yet personal communication wasn’t a big thing when you were out in a club. You’d catch people’s names but then rapidly forget them as information fused into the beats and melody. The most you’d remember afterwards would be a rosy-cheeked MDMA gurn. All the good ideas and deep bonds were made after the clubs and parties. Those small hours provided a fertile space where ideas were spoken, then heard and expanded upon. Or sometimes justifiably killed stone dead for being too bonkers. In my experience, those nights variously encouraged authors, fashionistas, songwriters, actors, designers of graphics, interiors and life, lawyers, accountants, artists, hairdressers, models, restaurateurs, carpenters, builders, black cabbies, drug dealers, bank robbers, junkies and whores.

One of those after-hours conversations began after seeing The Stone Roses at Dingwalls [May 1989]. I decided we had to form a band for the people in the clubs, people that had been listening to rock ’n’ roll just a couple of years before. The only live bands that had aligned themselves with the scene, drawn inspiration and given it back were New Order, the Mondays and the Roses, each of them having been together for five years or more. That Dingwalls show was one of the most amazing, inspirational gigs I’ve ever seen, before or since. It literally changed our lives.

My idea for the band was Liam singing, me managing and Liam’s brother Joe and his mates Andy [Jackson, bass player] and John [O’Brien, the band’s first drummer] playing the music. Liam initially said, ‘I can’t sing.’ So I pointed to Strummer, Shaun Ryder, Lydon. They were singers we loved – not being able to sing hadn’t done them any harm. He had it – whatever it is, he had it. All of that Balearic summer, people would come up to me and say, ‘Liam would make an incredible frontman.’ Including Jeff.

We’d met Jeff, Alan McGee and Bobby Gillespie at Spectrum. We used to sell them pills and we’d inevitably talk a lot – as you do when you’re refreshed. We quickly found we had similar musical tastes. We really got on, especially with Jeff. He was someone you could talk to about music; his knowledge was boundless without ever being patronising. If you talked about a song, or a musician, he’d always have a story about that song, or that artist. It just opened a world up. He was a proper fan, an enthusiast. That was something I had never come across before. It was really inspiring.

Coming round to the idea, Liam came up with the name Flowered Up on the day we decided we’d actually get the band together. Around that point, people would say they were loved up or fucked up or whatever – the name was a variation on that. I didn’t like it. I thought it sounded too sixties. But after mulling it over for a bit, it grew on me. I drew a logo that was based on the buddleia flower – the cone-shaped things that grow on building sites and railway sidings that are made up of hundreds of tiny four-petalled flowers. I picked one, pressed it and drew around the edges. There was the logo. The colours were perfect too. Buddleia is an urban weed that rises through the cracks. It felt like it was us.

Initially we wanted to write three songs and drop into a party as a live band. No one would announce it, the band would just come on and play. We talked Boy’s Own into letting us do it before we even had a song written then we camped to my flat in Regent’s Park where we spent four days and nights with a drum machine, a Portastudio and a notepad. By the end, we had three songs: ‘Sunshine’, ‘Flapping’ and ‘Doris . . . is a Little Bit Partial’. We’d all mucked together and knocked them out. I’d written the drum patterns and some of the lyrics.

After an article on the band in Boy’s Own and the successful execution of our three-songs-live performance idea at Kazoo – a friend’s club night in Paddington – things went insane. Crazed gigs in clubs and at parties, mad phone calls from A&R men pretending to be council estate kids. We signed to Jeff’s new label Heavenly and released two singles with them, got the cover of Melody Maker before the first one came out and the cover of NME the week it actually came out. Played gigs all over and signed to London Records for five albums. Partied harder than anyone else around, made a bad album and then found ourselves stuck.

The whole process of writing and recording the album was amateur. None of us had a clue what the fuck we were doing. We’d seen the band as a way out of our council-estate lifestyle and an extension of the party – of acid house itself – but we’d got ourselves into a drug-induced, near-coma state. We were scrambling around trying to learn a way to write, to find a formula to create new songs – while trying to keep control of a drug problem that was pulsing away at the heart of the band.

Some of us were full-on heroin addicts at that point, roaming around the streets of King’s Cross looking to score. Everything was becoming more and more clouded in the narcotic fog that had descended around us. It’s mental to think now of what we used to do to score in a pre-mobile phone age. An average day for me and Liam would involve waking up in the morning with horrendous drug hangovers and the full intention of getting on with things like going to meetings at London Records as previously arranged. By 1 p.m. we’d be in a crack house by way of a diversion, before not making the meetings at London. Most of the time the rest of the day was written off – some days I’d have to pretend I was still capable of acting like a manager. The crack houses we’d end up in were always tense and on edge, filthy and squalid with degradation peering out from the darkened corners offering a blow job for a speck of crack. There was a massive irony that we had left the loving, caring and inspirational friends who’d helped us on our way for this nightmare scenario. We had sacrificed Heavenly for this hell, and that absolute fuckup couldn’t be any more obvious. That said, I’d sometimes head to the Heavenly office after leaving one of those shitholes and hang out there as they were, thankfully, never judgemental. Obviously, we were rapidly rinsing whatever money we had. How we got away with it I still don’t know. Anyone running any business outside of the music industry would have taken one look at us and said, ‘You know what, go enjoy your drugs but don’t bother us any more.’ But the music business allowed us – encouraged us, even – to get away with a lot more than we should have.

We’d ended up in the position we were in because we were quite clueless. Being young and naive, we’d ended up making a substandard record [A Life with Brian] with the wrong producer [Nigel Gilroy]. We’d tried to rescue the record, ending up spending a load more of our own money trying to fix it in the mixing stage. Sonically the record is shit, it doesn’t stand up to any of the records we were inspired by, which was always the intention. And added to our inexperience, we were haemorrhaging money. We were paying out for a rehearsal room, trying to demo stuff, out of control on drugs.

The warning signs and alarm bells were all too apparent and our once-tight unit began to fragment and crack. One of the biggest problems for the band was that Liam would often not turn up. As much as I was missing meetings, he wasn’t making it to rehearsals. I’d get a phone call from Tim [Dorney] asking if Liam was with me at 11 a.m. The rest of the band had got together for a day’s work and the main person hadn’t bothered to turn up. They’d get a call from him about 4 p.m. telling them he was on his way. He’d then turn up at 7 p.m. That was happening all the time in London. We’d tried sending Liam away on holiday to clean up and we’d tried to remove any of the pressures of being ‘a pop star’ or whatever it was that was going on in his head, but none of it worked. The only viable solution seemed to be to get the fuck out of London.

Out of desperation as much as anything else we booked a residential studio in Sussex called the House in the Woods. Being there gave us the ability to just concentrate on the music and try to make writing a new set of songs the band’s main focus. The drug problem was still massive. Obviously, drugs travelled with us and there were always people who could scoot back and forth between there and London to pick up more gear. But, really, the only thing we needed to do day-to-day was to get people out of bed. It was pretty much impossible for them not to attend a session. It meant the band could spend time in the studio with their instruments, being a band. And that’s how ‘Weekender’ came about.

The original jam that the twelve-minute version got arranged from was forty-five minutes long. It was a continuous play, an evolution that went through all of the different sections of the song and a few more. It was extended and it was all over the shop, but there was something there. Over the space of a couple of weeks, we worked on it solidly and ended up with a twenty-five minute version.

We weren’t attempting to write a piece of music, or multiple pieces of music, that fitted into any particular style. It just came how it came, which is how songwriting had always worked for us. There was no formula, we weren’t specifically writing for a reason other than to see if we could do it and what would come out. The first two singles on Heavenly were an extension of that experiment. It was only when we signed to London that we got given a very quick and very serious lesson in how the music business worked. It was a massive wake-up call that we weren’t comfortable with. We didn’t write songs to get played on the radio; we’d started with the intention of writing music that could blend into DJ sets in clubs. ‘Weekender’ was as much a nod to that original idea as it was a rebellion against the conventions and restrictions of the industry we’d found ourselves in. The formative influences of the band were brought very much to the fore. Joe, the guitarist, was obsessed with Pink Floyd, Hendrix and The Who – that’s what he’d learnt to play along to. Jacko the bass player’s favourite band was Rush. John, the drummer, was a mod; Tim knew electronic music, and acid house was still a massive thing for Liam and me. Lyrically, the song captured our disillusionment with that scene. It had gone from being an underground thing to mainstream in a short space of time and there were weekenders everywhere – people who would go out on Friday and Saturday then be back in work on a Monday.

We still thought of ourselves as pretty hardcore – our two-year period where we were out every night was dedication as far as we were concerned. That element seemed to have gone, and it was never going to return. I was too young to have been a fully-fledged punk, but after getting to know [punk photographer] Dennis Morris, who’d toured with the Pistols, he’d talk about the weekenders of punk: people who’d go to punk clubs in a suit and come out of the toilet wearing a bin liner. I imagine it was the same in the 1950s and ’60s. So it felt like every major culture shift had those early adopters who lived it as a lifestyle and then later those people who were happy to dip in and get out. With me and Liam – and I’m sure with the punks and the Teds and the rockers and the hippies too – it’s only at the point where the something breaks big that you realise how special the underground was. Looking back, these things are always so short-lived.

Once we’d rehearsed and demoed the track, it was clear it wasn’t going to be a three-minute record. It had a bigger story to tell. We knew it was a vast improvement and a huge move on from where we’d been, musically. When it came to recording it, the most bizarre idea – and the best one – came from the A&R man Paul McDonald, who suggested we work with Clive Langer. In our whole time at London, it was the only idea he came up with that actually helped. We were a bit ignorant about Clive’s previous work apart from Madness, and possibly the suggestion was simply down to the fact that we were from the same part of London as them. We saw Clive as a bit too old, too establishment. When we met him, we connected in a way we never had with a producer before. It was firstclass. He had no desire to muck about with the song, he just wanted to tighten the arrangement. And he is a Camden boy just like us.

It was evident very early on in the jamming process that we had something special. It was clearly some kind of beast that warranted our full attention. That’s why there wasn’t a batch of songs written at that time – all the attention was focused on getting this one track right. Also, as a piece, it’s as long and as varied as an EP of songs would have been. The only other song written around that time was ‘Better Life’ [released posthumously as the Heavenly 7-inch, HVN38, in the summer of 1994], but that came about in down time in the studio while we were recording ‘Weekender’.

Between the writing and recording of ‘Weekender’, Jacko left the band. He thought the drummer was too limited and he had had enough of the drug situation. John Tuvey was pretty restricted – he’d learnt playing along to mod records; he was tight but he didn’t have any flare. When Jacko left, we lost a key ingredient. We didn’t realise that until he’d gone, and by then it was too late. When that happened, I began to realise how much we’d been winging it with the initial writing process we had. We knew the fundamentals of writing a song, but who did it and where it came from, we didn’t have a clue. We’d fumbled through to that point: ‘Phobia’ had been written by Liam and his girlfriend Tammy; ‘Hysterically Blue’ was all me; ‘Take It’ was a lyric we’d appropriated from a little song Joe Strummer plays on the piano in Rude Boy. After ‘Weekender’ all that seemed to have dried up. Liam was in the room but he wasn’t contributing any more than he had to. Joe had dried up completely, he’d starting wacking power chords over everything and it just wasn’t advancing the sound at all. Tim was becoming more and more frustrated with the lack of progress in any direction, which was totally understandable. That said, we all knew we had this beast of a track and we had a feeling that if we got it out, things would open up for us.

From the outside it might seem pretty incredible that we managed to get anything done at all, but there was an insane amount of enthusiasm coming back to us from people like Jeff, from London Records initially, and then from Rob Stringer and Columbia. After London tried to force us to work on a three-minute edit of the track, we managed to wriggle out of that deal and went straight to Jeff, who by then had a deal with Columbia.

We were all incredibly keen to get back to Heavenly – it seemed like a massive positive going forward. Ahead of a deal being done with Columbia, a bunch of head honchos from the label came to our rehearsal studio to hear the band play live, particularly to hear them perform ‘Weekender’. Rob Stringer, their legal man Déj Mahoney and Tim Bowen – apparently the man responsible for signing The Clash – and Jeff came down. When the small talk was over and the band got ready to play, Liam refused to perform. Stone cold he wouldn’t have it and fucked off. In his head, he didn’t think it was necessary to pander to music biz knobs. My take was that his bottle actually went. He was increasingly becoming more isolated from the rest of us and obviously wasn’t enjoying it much any more. The rest of the band played through four or five tracks without vocals, including ‘Weekender’. Thankfully they were dynamite and the Columbians were happy, but the whole thing was tense and embarrassing. I’m still not sure how I managed to manage that, but miraculously I did, and we got an album deal done.

Jeff had the idea of doing a film – a kind of mini-Quadrophenia – for the whole track. We’d already worked with the director Wiz on the video for ‘Take It’, and he came at it with a load of energy. The idea was less that it was a video for the track, more that the track became a soundtrack to a film. The fact that Andrew Weatherall remixed the track only added to the excitement. We’d always wanted to get Andrew to do something for us since writing those first three songs; he was still our favourite DJ. Boy’s Own magazine was the first place to write about us and we’d always wanted to play one of their parties. Musically, this was the first Flowered Up track he was up for having a go at, which added a lot more clout.

When ‘Weekender’ came out, the reaction was a mix of pure excitement and quite a bit of shock. Not many people knew what Flowered Up were capable of as a band, but there were a few of our peers who were just made up that we’d hit a level that they’d always believed we were capable of. Then there was shock from people who’d heard the album and were now wondering where the hell this thing – this beast – had come from. So, for a short time, there was a renewed excitement that this was a new beginning.

Around the time that ‘Weekender’ was released, Barry [Mooncult, Flowered Up dancer], who was a glazier by trade, had been asked by the firm he worked for to fix a quarter window in a front-door panel of a three-million-pound mansion on a private road in south London. Literally the panels down the front door, a tiny thing. So the firm gave him the keys and the first thing he did was go and get another set of keys cut. This was before he’d even fixed the window. He knew the house was empty as there was a note on the gate saying that it had been repossessed by Midland Bank. He called and told me what he’d done, so I said, ‘What’s the address? I’m coming now.’

The house had been owned by a guy called Terry Ramsden. He’d made a fortune off betting on horse racing, had been arrested in California over Japanese bond fraud and was awaiting extradition back to the UK for trial. He’d tried to buy Walsall football club and was basically just a bit of a character.

About five of us moved in for a week. Once we were in there, we were going through wardrobes to see what was there. We found a load of Ascot day suits, complete with top hats that we’d wear in the jacuzzi. Straight away, we had the idea of having a party there. We knew the authorities would be notified that people were coming and going, so we had to do things quickly. There were different squatting laws back then – anyone would have had to go through the courts to get us out – so we did things by the books and put up signs saying it was being squatted legally.

The party took about two weeks to organise. We booked DJs and a PA system and printed a thousand tickets that we sold at a tenner each. Paul Oakenfold and Terry Farley played, along with a couple of lads from the estate. We converted the bedrooms into bars and ran it like a club. The party itself was berserk. Gerry Conlon, one of the Guilford Four, turned up. They’d just made the film In the Name of the Father and he’d made a load of money. He turned up with about thirty hangers-on who all had cases of beer on their shoulders. Kylie was meant to be there; Hanif Kureishi went and based some of The Black Album on it afterwards. Every so often you’d hear ‘Weekender’ coming from somewhere – whether it was one of the DJs or in one of the bedrooms, people kept requesting it all the time. The police made several visits but were fully aware that if they stopped the party, they’d have a load of crazies flooding out onto a private road. They had to let it burn itself out.

Around six in the morning the PA shut down. The hire company had only been paid until 6 a.m. Whoever had booked the PA hadn’t bothered to tell them it might run later. At this point there was a mansion full of hardcore veterans of acid house parties who weren’t going to go home – they were on their fourth or fifth pill and raring to go. We paid the PA guys about four hundred quid to stay for another hour and a half, which is all they’d do. Through that period the house started to get deconstructed: sofas started going into swimming pools, twenty-foot curtains were torn down, all the banisters on the staircase got pulled up. The whole place was properly, properly wrecked.

By the end, it looked nothing like it had when we opened the doors. It was ruined. The last people to leave went on the Monday morning; they’d been roaming about dressed in their underpants and whatever was left of the curtains. Every penny we’d made on ticket sales and on the bar we’d spent. There was a massive drugs bill. In fact, we probably left there owing more money to someone somewhere. We walked away from there with nothing.

Believe in Magic – Heavenly Recordings: The First Thirty Years by Robin Turner is published by White Rabbit Books