When I suddenly remembered it, I had to do some digging. Happily, not all that much – if you’re some level of obsessive, you almost certainly have some way of organising what you have, even if your preferred method is chaos. The library worker that is me, though, things are a bit more regular, and in one bookcase I still have a string of Melody Maker issues from 1991 to 1994, a remnant of my stretch as a fairly active musical Anglophile in California.

This issue was from November 19, 1994, but the cover story wasn’t about Britpop – not yet. Instead it was emblazoned "Touched By The Hand of Mod", and was one of those MM issues with a central section where it was less about a particular act as the focus as the attempt to classify a seemingly emergent scene as such. There were a variety of stories at once acting as an explanation (and a very, very specific one, largely about and for white dudes) and a slight questioning of said scene. But you could easily sense the imminent sliding into a later Britpop framing, a limited stereotype of one, where Paul Weller was the god still in exile and so forth.

And right in the issue’s centre, just as I had remembered it, was a black and white photo that took up most of two pages. It showcased a band I might well have seen a quick mention of in earlier issues here and there, but which I definitely fully noticed now, not quite THAT Suede cover story from early 1992 but almost the same sense of a new coronation. Five young men in a row, on Savile Row at that, all in sharp suits, lead singer behind sunglasses and showing off a bit of a pout.

Caitlin Moran’s accompanying story delves into the working-every-opportunity methodology the three founding members applied, taking advantage of being young men with good looks and brio in a milieu set to favor them. It touched on their quickly making a name and getting connections with barely a couple of songs ready, go-getters to the max. But perhaps she said it best in the opening sentence, a sense of everyone involved playing the game, knowing the score: "It has been decided, already, that Menswear are going to be famous."

"I think we were one of the prototype boy bands that played their own musical instruments, that kind of became quite big in the noughties. I wonder sometimes if that’s what the record company had in store for us, but then we went all country rock on them."

It’s a few days before my Melody Maker spelunking and I’m having a very pleasant Zoom chat with that lead singer and person offering this thought, Johnny Dean, as well as guitarist Chris Gentry, one of the other two founding members from earlier in 1994, and drummer Matt Everitt, recruited soon thereafter. The occasion is the new box set on Demon, The Menswear Collection, covering everything the band did together and following exactly that capsule description Dean’s offered for their history. It grew out of Demon contacting Dean via Twitter for a possible single album reissue, and things went from there.

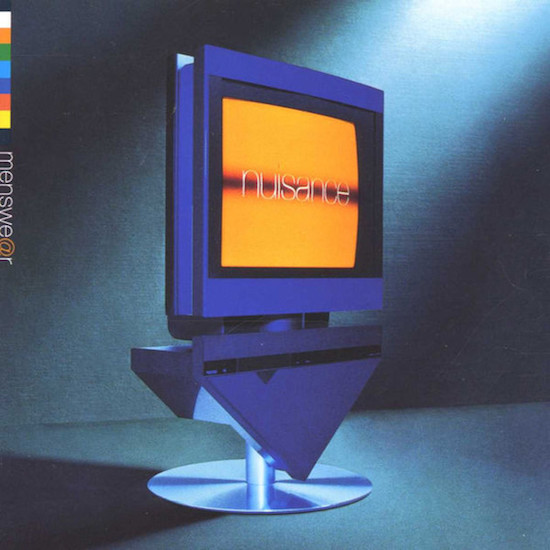

Dean and I have been mutual social media follows for some years now, thanks to the fact that along with a clutch of other American writers I still fly the Menswear flag. I had to let go regular MM reading due to a money crunch as a cash-conscious grad student at the end of 1994. But even then, thanks to the Internet and occasional mentions here and there, I soon heard scattered reports that the band had indeed started making a series of high profile UK chart and TV appearance splashes, especially with the single ‘Daydreamer’. Meanwhile my side career in writing about music was starting to emerge, various promos would come down the pike, and that included Menswear’s late 1995 debut album Nuisance.

I stand by that album to this day, spiky, immediate, absolutely and utterly indebted to its forebears and making the most of exactly that, a catchy pop-rock album with very crisp 90s production, perfect for CD. I started scrounging for their import singles and was even more delighted to find the B-sides were pretty great too, even the remixes, covers and live cuts. (Thankfully they only gave in twice to the two-CD single scam.) Their only tour of America soon followed, opening for the Charlatans, and even if the Menswear fans in (again) a heavily Anglophilic audience in LA were outnumbered by default, I still remember the cheers from the hyperfans up front for their set. I remember wishing I could get a T-shirt and hoping they’d be back one day.

Except they never did, and then a couple of years later there was a report of, indeed, a country rock album only released in Japan called ¡Hay Tiempo!, and then that was that. It seemed like Spinal Tap accelerated and concentrated.

In talking with Dean, Everitt and Gentry there’s a definite sense of double nostalgia at work, theirs for their band experience and mine as a fan, tied in with the fact that we’re all nearly the same age, me just being a couple of years older. Asking anybody to consider their early twenties from a couple of decades plus on is to invite rumination and at least some form of learned experience, and the band members are clear enough about theirs.

"It was completely and utterly unhinged, the whole thing, the speed of it," Everitt recalls. "You start to think about it, it’s quite funny. But it took me a long time to feel anything other than like, ‘I don’t want anything to do with it.’ I used to get those occasional interviews, requests from magazines about, ‘Oh, what’s everyone up to?’ And I’d be like, ‘I don’t want to do it, nothing to do with it.’"

Dean agrees: "I think we all ran away from it, didn’t we, to some degree? I certainly did."

"I only went away from it in a way where it was behind me and I didn’t want to look back, I wanted to go forward," Gentry adds. "I was so young when the band broke up, I think I was only 19 or something. But I’ve never had any bad memories from there. It’s been a bit for me like being at university. I kind of look back on them really fondly now. Like that was like my…"

"School of rock," Dean interjects.

"Exactly!"

The concept of too-much-too-soon, success as a double-edged sword, these all have their place in the preset mythologies of fame much as Moran’s opening statement was as well. Perhaps the best thing about both the box set and its timing is that there’s been that space for people to look back and remember things with a fonder, calmer eye. It’s not for everyone – neither the other founding member, bassist Stuart Black, nor second guitarist Simon White are actively involved with promoting the project, and their stories are their own to tell.

As the conversation continues, what the three share is a way of thinking about their annus mirabilis that I’ve not always heard from musicians who had similar moments — that it’s not so much that the album works as an album, but as a documentation of a time and place from people primed, ready and willing to be a part of something.

"A lot of these bands," recalls Gentry, "like Blur, Oasis, even Elastica, I was a fan of them. All of a sudden, we were hanging out with them. I always played in bands, as Matt did, when we were kids."

"Just wanted to be signed. Just signed, that was the thing," Everitt adds.

"I’d have been happy just being a little indie band that got on ‘The Chart Show,’" Dean offers. "But things had changed so much that indie had become the mainstream."

"[Nuisance] is very instinctive and it’s very immediate," says Everitt, "and it’s quite true. For all its faults, it’s a really accurate representation. It’s not trying to be anything other than exactly what happened when we played, and those songs were written really quickly.

"Everything from culturally and musically what’s happening in clubland and stuff, we were just soaking all that up," Gentry remembers.

"It was very haphazardly done," Dean continues. "If you listen to that album, ‘Daydreamer’ doesn’t sound like it even belongs on it, really. It sounds completely on its own, really. It’s like a sore thumb, because we just went, ‘Let’s write a Wire song.’ And then I think it was like, "Let’s write a song a bit like Primal Scream," and we got ‘Stardust’. I don’t know how we ended up doing… how did we end up becoming country rockers?"

"I think we were just trying to run away from Britpop," responds Gentry.

"I guess the quick answer to that would be cocaine," Dean answers with wry calm.

There wasn’t the time to go fully into Menswear’s Japanese fame – represented in part on the box by a demo called ‘You’re Never Alone In Tokyo’ and a full-length ad jingle, ‘People I’m Hooch’ – but whatever the reasons for its sole release being in that country, ¡Hay Tiempo! is, it turns out, a bit of a gentle revelation. It’s country rock indeed but in a very early sense of it, the Byrds/Gram Parsons era, Dean not trying to sound like a grizzled cowboy but just letting his singing suit a further enjoyable context.

Yet the influence had been hiding in plain sight – a couple of those Nuisance B-sides had a bit of spaghetti western swagger, and their post-Nuisance standalone single ‘We Love You’ had some steel guitar in the break. Gentry credits the tour with the Charlatans as a sonic connection as well – ¡Hay Tiempo! has a lot of Hammond organ throughout. Dean further marvels that "there’s a whole other album’s worth of that stuff", referring to the often quite enjoyable ¡Hay Tiempo!-era demos of otherwise unreleased songs that make up the bulk of the set’s fourth disc.

As the trio’s other comments reflect, they dealt with the time after the band in their own ways, but for Dean, as he has frankly discussed for some years, there was an extra factor with his mental illness, along with the recognition that it was untreated at the time of their greatest fame.

"My idea of what happens is going to be different from someone else’s," he notes, "especially when it comes to stress and stuff. It’s a different experience being a frontman, I think, than it is hiding behind an instrument. It’s very different, and especially when there’s focus on you. I think it can have quite a damaging effect on people."

Everitt adds, "I think when we were doing it, nobody even stopped to think, ‘Oh, do you think maybe a day off?’ And this is not moaning about, ‘Oh, as a musician, it’s so fucking hard.’ It’s not most of the time. But the emotional toll of things happening that quickly, the emotional toll of that much attention, especially on John. Adele canceled… is it three Wembley Stadiums? It’s like, ‘Wow, that cost her millions.’ And it was the right thing to do, because she obviously needed some time away. Nobody would have ever let us fucking get away with that."

Thinking on Dean’s boy band comment, and further reflecting on how the band was presented almost from the start, also intertwines with a question of legacy – something that may seem strange from one perspective, but the existence of The Menswear Collection alone makes the case. In light of recent new interest in ‘landfill indie’ of the 2000s we talk about that briefly, though Dean admits to having been so burned out by his own experiences that he didn’t follow things as much then, saying "Having a peek behind the curtain ruined a few things for me, I think." Gentry mentions his appreciation of the Strokes, the White Stripes and Interpol, as well as saying that to his feeling there were generally better records made in the 2000s in comparison.

"But none of those bands did it as quickly," adds Everitt to general agreement. "None of those bands did it in that period of time."

It’s that sense of the sudden flash captured in moments – the Melody Maker center spread, the fresh out of the gate Top of the Pops appearances discussed in the box set’s liner notes, the other clips you can find on YouTube, my own smeared but still enjoyable memories of a single show far away from their home – that may explain my continuing fondness for Menswear. Putting everyone’s memories and experience into a frozen place isn’t the best thing for either an artist or an appreciator of art and however short our collective chat, there is something satisfying in knowing we’ve all made it this far in our own ways.

But, to conclude on another exchange between the three, there’s both a value and a knowing humour in remembering those days still:

"There were no consequences because we were too young, and the audience was too young to have any consequences," thinks Everitt. "It was just, ‘Let’s enjoy it as much as possible.’ And that’s a really freeing thing, when you’re not worrying about your career, you’re just doing what feels like it’s the right thing to do."

"Also, 95 was, I think, it was a real time of optimism in the world," adds Gentry. "Positive change was coming, it felt like. Everything was just good, it was coming good at that point.

"Yeah," responds Dean. "It turned out that we were all just really high."