“After Clift came Brando, and after Brando, James Dean. Clift was the purest, the least mannered of these actors, perhaps the most sensitive, certainly the most poetic… He gave at least four performances…that remain among the finest anyone has given in the movies.” – Peter Bogdanovich

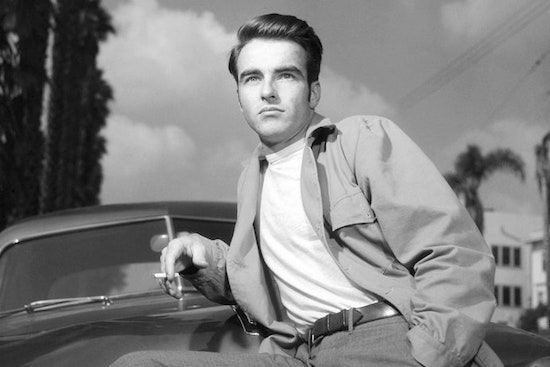

On paper at least, Montgomery Clift had everything: matinee idol good looks, natural acting talent bolstered by training from legends of the New York theatre, the education of an aristocrat. It’s why Hollywood pursued him for more than a decade, trying to tempt him over to the movies with increasingly tantalising offers, until he finally relented. Cinema audiences saw Clift for the first time the year he turned 28, in post-WWII drama The Search, which earned him his first of four Oscar nominations, and the western Red River, which was a huge box office success on release. These two films, each a showcase for a novel kind of leading man practicing an immersive new style of acting that would come to be known simply as ‘the Method’, made Clift an instant star.

Not two decades later, Clift would be gone, having been absent from the screen for four years and with serious drug and alcohol abuse having left him unrecognisable and unemployable. Films like A Place in the Sun and From Here to Eternity made Clift a rare performer enjoyed by audiences and critics alike, but when he passed away in 1966 aged just 45, the actor had long since become best known for his personal dramas, in particular a disfiguring 1956 car accident that undid his once near-saintly beauty and accelerated his spiral into ultimately fatal addiction. Monty Clift started his career at the top, but it’s the gloomy end – and what came after – that has ruled conversation about him since.

Though he was publicity-averse in his lifetime, Clift’s private life has been a source of ghoulish fascination in his death, with speculation over his sexuality (Clift was gay, or possibly bisexual), unusual upbringing (along with his siblings, Clift was educated by private tutors on family travels throughout Europe and America) and relationship with a mother allegedly obsessed with raising her children as if they were nobility. Biographers have attempted to make sense of Clift in his absence, declaring him a tortured gay man, or an eccentric with an Oedipal complex. Whatever the reality, such fascination has only served to obscure a more important truth: that Montgomery Clift – as the person who brought method acting to the screen arguably before anyone else (Clift beat Brando into movies by two years) and who popularised the troubled young antihero figure prior to James Dean becoming the poster boy – is one of the most important actors of the 20th century.

What we know of today as method acting originated in the mid-1940s in New York’s then-fledgling Actors Studio, where Clift took only a few lessons before unceremoniously quitting. According to Arthur Miller, Clift thought Actors Studio teacher and Method pioneer Lee Strasberg a “charlatan”, while Clift himself always gave most credit for his naturalistic performing style to mentor and celebrated Broadway actor Alfred Lunt. Nevertheless, method acting might broadly be defined as a study-intensive, inward-looking technique designed to give the actor a sense of their character’s unique psychology – and Clift certainly practiced some form of that.

To prepare to play a GI in The Search, his debut film, Clift moved into an army engineers’ unit for a period and rewrote his character based on his experience there. He would continue in this vein throughout his career, sleeping overnight on death row in San Quentin Prison to prep for an execution scene in A Place in the Sun; spending a week in a Canadian monastery to play a Catholic priest in Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess; learning to box and bugle for From Here to Eternity. Such behaviour, which today might be simply considered the mark of a committed (if still uncommon) actor, was unheard of in Clift’s day.

Also unusual was Clift’s sensitive on-screen persona in a time when many of the leading men were doorframe-bothering hulks of masculinity. The contrast was obvious in a pair of films Clift made opposite two of the most macho stars of the age: In Red River and From Here to Eternity, John Wayne and Burt Lancaster respectively do some of their most memorable work, but next to the subtle, conflicted Clift, their uncomplicated machismo only appears limiting. That Clift seemed like something close to real – photographer Richard Avedon described his style as akin to “reportage” – is the reason why modern actors play like him rather than John Wayne.

Clift isn’t remembered today in the same way as some of his contemporaries, immortals like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando and Kirk Douglas. It could be because while Dean and Marilyn were preserved beautifully in Hollywood amber as a result of their own untimely tragedies, Clift suffered an uncomfortably protracted public decline before dying, or that while Brando and Kirk enjoyed towering careers of more than five decades, Clift’s addictions wouldn’t even allow him two. Clift’s story just isn’t especially glamorous. Nor were many of the parts that he played.

Unlike Brando at his magnetic peak, Clift rarely played roles sexy or cool. Pretty though Clift was in his heyday, his were never characters to emulate; often, they projected terrible loneliness and pain. (Hitchcock perhaps summarised Clift best when he said the actor “always looked as though he had the angel of death walking alongside him”.) And while Brando’s improvisatory playfulness and shimmering intensity would rarely allow the audience to take their eyes off him, Clift’s technique could in contrast be invisible.

In I Confess, Clift’s priest Michael Logan comes under investigation for the murder of a lawyer, though we know from the first scene that a parishioner has already owned up to Fr. Logan during confession. Despite increasing pressure from the police, Logan never spills, though look closely and you’ll see the conflict roiling within him in Clift’s minute, almost imperceptible facial expressions. As Clift’s I Confess co-star Karl Malden put it, Clift could be so quietly immersed that “he actually sinks into the flesh of the story”. Clift just didn’t go in for attention-grabbing histrionics very often – though when he did, in the second half of his film career, it only fanned the flames of gossip about his personal life.

Following his fateful car accident, Montgomery Clift didn’t just look different, his broken handsomeness now lending him an everyman quality; with the left side of his face left ‘frozen’ due to nerve damage, Clift compensated by becoming a performer reliant on gesture and expression through the eyes. This all-new, more animated Clift reached his peak in The Misfitsand Judgment at Nuremberg in 1961, in which the actor gives portrayals of two irreparably damaged men so convincing that some assumed he wasn’t acting at all.

It’s easy to watch a jittery Clift in his cameo as Judgment at Nuremberg’s Rudolf Petersen, a German baker with learning difficulties who has been sterilised by the Nazis, deliver lines like “Since that day I’ve been half I’ve ever been!” and imagine he might be drawing on the memory of his car crash and subsequent addiction issues. Indeed, legend has long maintained that Clift, at this point so bombed on drugs and alcohol he could no longer remember lines, had been asked by Nuremberg director Stanley Kramer to just improvise his way through the scene, the result being not a performance but a recording of a washed-up actor having a very real meltdown. (Not that it ever made much sense that Clift could be so un-directable and then, while apparently still at the height of his addiction, deliver such a controlled performance in the film he made right after Judgment at Nuremberg, 1962’s Freud.)

One of the most effective moments in Making Montgomery Clift, a 2018 documentary about the Clift mythos directed by Hillary Demmon and Clift’s nephew Robert Anderson Clift, comes when Clift’s Nuremberg performance is shown to us side by side with his own heavily annotated script – where the dialogue matches this singular performance word for word. It’s definitive proof that Clift was, even here at the troubled end of his career, still totally capable of great professionalism, though what’s remarkable is that it even took this long to dispel the myth that Clift wasn’t faking, that the power he mustered in this scene couldn’t be just an act.

There’s no great mystery as to why the private life of Montgomery Clift continues to be a primary source of fascination. Clift’s personal story is tragic; a story about a talent as promising as Monty Clift being ultimately shattered by that person’s own personal demons can’t be anything but. Still, here on his centenary, the man is long gone, while the performances that remain are as powerful today as they were more than half a century ago.