‘Secretly’ was released in May 1999 and became a hit in the UK and throughout Europe, and Leigh had the pleasant problem of not being able to release a third single from the album because

they couldn’t get ‘Secretly’ off radio playlists! The video was directed by Italian film-maker Giuseppe Capotondi, and the song was on the soundtrack of American teen drama Cruel Intentions, an adaptation of the novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses, but set in 1990s New York City instead of eighteenth-century France. While our video was played on rotation on MTV, we toured enormous festivals that summer of 1999 – playing to 90,000 people at Spodek in Poland, 96,000 at Roskilde in Denmark and 150,000 at Germany’s mega Rock am Ring. Leigh likened us to a conquering army.

Headlining Glastonbury Festival in 1999 on the final Sunday night of the decade was our pinnacle. As everyone knows only too well, the Glastonbury rain and mud can be as legendary as

the bands. But that year, when we came on after Lenny Kravitz’s set, the clouds parted and the sun came streaming through. I stood on the Pyramid Stage, looking at a 120,000-strong crowd

stretching all the way back to the tents in the distance. In 1995, we had missed the beginning of our slot, running late onto the NME Stage at midday; we had been the first band on, we performed four songs, and that was it, done.

Four years later, we were back, headlining the Sunday night with a seventeen-piece orchestra and playing to a huge crowd. The set is featured in the BBC documentary Glastonbury’s Greatest Headliners, but back then, there was grumbling in the music press that our ‘stadium punk’ wasn’t right for headlining the festival. In the late 1990s, Britpop bands had dominated the Pyramid Stage for some years, and even though we were a hugely successful band by this point, we still felt we had to prove ourselves worthy. Part of the reason I think there have been so few POC headliners at Glastonbury is because diehard fans and sections of the press and music industry think only rock or indie bands deserve the slot. We were rock through and through, but to some people, having a black front woman and a groove to our sound meant we weren’t rock ‘enough’. Festival organiser Michael Eavis did something special when he gave us a seat at the table, letting it be known to all that Glastonbury would have a more diverse future. He was ready to take a risk and withstand the backlash. His daughter Emily followed suit in 2008, when she put Jay Z in the top spot.

We were on form and ready to give everyone the gig of their lives. Our set the previous day – on a speedway racetrack at the Hurricane Festival in Germany – had been one of our best

to date. I remember thinking afterwards, If we play like that in Glastonbury, it’ll go off! To get himself psyched up, Mark got our make- up artist to put Maori- style warpaint on his face as if he was going into battle. He said to her, “I need something on my face that says, ‘Fuck off, the lot of you.’ “ She then put Maori tattoos on his face. Nowadays that might be considered appropriation, but to Mark, an ex-rugby player, it came from a place of love, and it was meant to give him strength in the face of adversity.

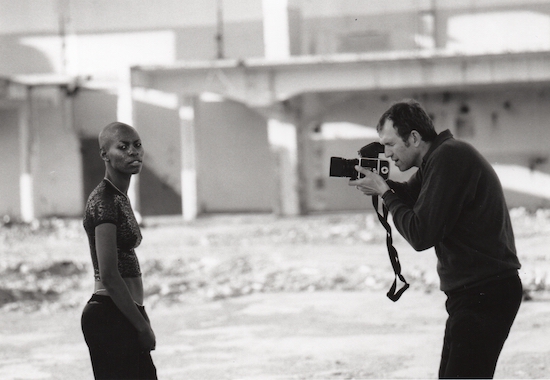

A young designer called Cathryn Roberts put together something very special for the day. She’d already made a load of my crazy looks, but for Glastonbury she went all out, designing a

suit made out of ole-skool cassette tape, to reflect the light. It was shiny and mad and had the desired effect – I was like a lightning bolt across the stage.

On that tour we had a huge stage set made out of 30 square inch mirrored tiles. Each section could be independently controlled, so we could create a lot of drama depending on how the lights hit them. This was important, because our songs are quite varied, and it gave us a simple way to instantly change the mood from soaring riff-tastic overtures, to intimate, delicate lullabies. The show was like a drunken argument: one minute you’d be jumping for joy; the next minute you’d be on the receiving end of a creative bitch slap.

We launched into ‘Charlie Big Potato’ and, from the first second, it went off. People were screaming, singing, dancing and waving flags. As I sang, I climbed onto Mark’s bass drum and leapt off, running towards the front of the stage and the crowd. By then, Mark had a special contraption made called ‘the Skin protector’, which was a metal bridge that went over the bass

drum and bolted onto the drum riser, so I couldn’t crack his kick drum when I used it as a trampoline. I was performing at full steam, turned up to Number 11 and taking no prisoners.

We were all feeding off each other and the audience – the energy was electric. I jumped down to the crowd barrier and the fans reached for me. I was to discover that cassette tape is not the strongest of materials, so the fans were able to tear off pieces of my outfit. Song by song it began to disintegrate, leaving streams of tape all over the stage and in the hands of the front row. I didn’t care; it added to the joy and unpredictability of the show and became a whole new look.

As I climbed back onstage, I could see people jumping up and down all the way to the horizon. Mark looked like a northern Incredible Hulk smashing his fists into the drum kit. We had to screw it into the floor every night to stop it crumbling to pieces under his assault. I could see Cass was loving every second, spinning around, ruling the stage, dreadlocks flying behind him. Ace, on my right, attacked his guitar in that deranged way that sent the crowd ballistic.

We all looked on top form. I had no idea that Ace was in intense pain with seven prolapsed discs in his back from constant touring. He had to have steroid injections every day and lie on ice packs after each show. During the gig, he was wracked with nerves, not wanting to play a wrong note. To the outside world he was on top of the world, but on the inside he was thinking, Don’t fuck up, don’t make a mistake! I almost feel bad for clambering all over him now!

We sang ‘Hedonism’, and when we got to the chorus, the crowd sang back in unison at the top of their voices: Just because it feels good / Doesn’t make it right! I saw Michael Eavis at the side of the stage. His wife Jean had died earlier that year, and the whole country mourned with him, so I dedicated ‘You’ll Follow Me Down’ to her, and blew him a kiss. I gazed at a stunning sea of lighters while the light reflected off what was left of my outfit and it looked like I was on fire.

We were the last band to play on the Pyramid Stage that century. It was an incredible experience, but it also felt like the end of something at the same time. We were interviewed by Radio 1’s Jo Whiley as soon as we got offstage, and I remember feeling so happy it was almost like I was floating. She asked us, ‘What are you going to do now?’

We laughed, saying, ‘We’ve got the string players with us and we’re going to get drunk all the way back to London.’ We were as good as our word. Sitting on the bus later, drinking

wine and celebrating, I thought, Is it ever going to be as good as this moment again?

It Takes Blood and Guts by Skin and Lucy O’Brien (Simon & Schuster UK) is out now in hardback, ebook and audio.