As livestreams look set to be the only way we will be experiencing live music for the forseeable, one company is looking to make better spaces in our homes with a curated programme of intimate transmissions through its own curious wooden speakers.

When full Coronavirus lockdown was imposed back in March, the number of livestreamed gigs exploded, a simultaneously desperate and inspiring attempt for an entire industry to salvage something from a whole season of wiped income, and for fans to remain connected to the music they love. But livestreams are poor substitutes for the experience of experiencing a show in person.

As a fan and reviewer I’ve tuned into a number of online events, from one-off YouTube shows by bagpipers in their bedrooms, to evenings cramming 20 short pre-recorded slots into a night. As much as I want them to be good, these events are pale imitations, not much good for anything beyond trying to keep us all together and afloat in times of crisis. Unfortunately, most live streams have been terrible. I’ve wanted so badly for these things to scratch the itch left by the loss of live music. As lockdown looks to continue through into the middle of 2021, turning live broadcasts into sustainable economies is a pressing concern for musicians who no longer have a touring income, and for audiences, there must be a better way.

Nick Dangerfield was similarly dissatisfied with live streams, long before Covid struck. Back in 2016 he began developing an idea that would remake live streams into intimate home concerts, ditching grainy videos and instead restoring full stereo sound. He wanted to find a means for musicians to transmit live into our homes from theirs, encouraging us to sit down to listen with focus. His vision was for livestreams to be treated as actual events, not like another Netflix. The result was Oda, a set of specialised speakers and a programme of live events that would be more about creating an engaging space in which to listen, rather than the tech itself.

The Oda speakers are designed specifically not to look like a piece of tech. Looking more like an item of furniture, they are narrow cherry wood squares the size of a 3LP box set that can also be used as normal bluetooth speakers. The speakers are controlled with a little black tower called the ‘lighthouse’, which has a knob, a button and a light, which indicates when a performance is on. There are two speakers because they are designed to recover the proper stereo sound many people have lost through using individual wi-fi speakers and laptops. "Oda is Spanish for ode," Nick explains (he is Spanish). "Oda is because it’s an ode to these great artists – I imagine it as a shrine, where the ‘lighthouse’ controller is a candle and the dedication is to the artists."

Oda isn’t really primarily about a new set of speakers, but about our behaviour as audiences and the economies of streamed events. Tech companies will put a cheesy emphasis on experience to sell any device, and so I am initially sceptical of its promises. However, there’s an attention to detail in Oda that I didn’t expect. Their aim, Nick says, was to design a live music experience for the home, one that didn’t just give you a piece of technology, but that changed behaviour around live streams, creating a scenario in which you would sit down to actually listen to a show in the evenings, where there isn’t a screen to stare at. It’s designed specifically as a listening experience – there is no video – and in a bold move, there’s no archive. Oda are also at pains to point out that these speakers have no microphones – while you might be listening closely, they are not.

Nick also describes a different sound balance designed for live music. This comment, along with the unlikely size and shape of the speakers made me think I’d be getting a sludgy Suicide-like DIY basement sound, but when I turn it on and link it up (via a sort of wifi handshake through an app) the holding feed before the performance starts is live audio of the street by Tompkins Square Park. I can hear sirens and the ice cream van move in the background, snippets of people’s conversations pass across the stereo image as they move down the street. It’s sharp, spatial, and has a sort of tactility to it, with a depth that makes it feel like sitting at a window, which of course, it is, only the window is in New York and I’m experiencing it in my Southend living room.

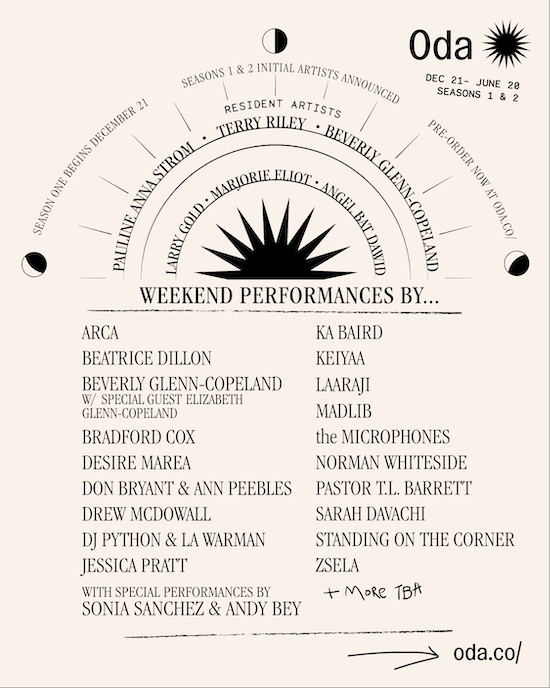

The speakers are considered part of the infrastructure of this ‘home venue’ setup, so they’re priced as close to cost price as could be squeezed without compromising artist fees. They will be $299 when it starts, going up $100 once they get established, then there’s a membership at $79 per season. It’s like a venue membership scheme, or paying ahead for your next 25 concerts. However, the artists don’t play one concert each, and instead sign up to host a ‘weekend with’ or to be ‘residents’, and a few artists doing special performances. 25 artists have already been confirmed for the first and second seasons, with more to be announced.

A ‘weekend with’ will include a number of performances, while a ‘residency’ lasts three months and involves artists spontaneously drifting through the weekdays, the idea being that you begin to live with someone’s sound and music. There are nine residents confirmed for the first season, including West Coast synthesizer musician Pauline Anna Strom, whose blindness led her to build a vivid alternate reality; the cellist, arranger and producer Larry Gold – cellist for The Sound Of Philadelphia as part of the MFSB house band, and who wrote string arrangements for Erykah Badu, Timbaland, Lana Del Ray and others (and who says he still practices cello at least two hours a day); meditative new age composer Beverly Glenn-Copeland; and Marjorie Eliot, who has been hosting intimate weekly jazz concerts in her living room in Harlem for many decades, and was once called the "secret jazz queen of Sugar Hill"; plus Terry Riley transmitting from Japan and Angel Bat Dawid transmitting from Chicago.

Confirmed weekend artists include reclusive hip hop producer Madlib, South African multi-disciplinary artist Desire Marea from FAKA, singer songwriter Zsela, 70s soul musician Norman Whiteside, ex-Coil member and ambient musician Drew McDowall, Mount Eerie’s Phil Elverum, composer Sarah Davachi, electronic artist Beatrice Dillon, Deerhunter’s Bradford Cox, singer Jessica Pratt, artist and queer activist Arca, New York City jazz collective Standing On The Corner, multi-instrumentalist KeiyaA, legendary Chicago clergyman and gospel musician Pastor TL Barrett, Memphis soul music royalty Don Bryant and Ann Peebles, producer DJ Python, and experimental vocal artist Ka Baird.

How much someone plays and for how long really comes down to the artists – Oda doesn’t require them to stick to a predetermined schedule or framework, but just asks for a minimum commitment. The hope is that you might hear someone’s daily instrument practice in the morning one week, and an epic long form synthesizer jam the following, and artists can also include talks and conversations – Don Bryant and Ann Peebles, for example, will be going through records together and talking through their stories.

Oda is only just launching, and its focus (initially at least) is more on experimental than mainstream music, but also carves out valuable time with some underappreciated session musicians and lesser celebrated legends from soul and jazz. A recent press preview week broadcast sunset shows from the New York time zone with Marjorie Eliot, Ka Baird, The Microphones, Drew McDowall, Norman Whiteside and others.

Whiteside gave a charming performance lecture which traced routes through his career via the sonic motifs that had defined it. Dowall was able to create a depth of electronic ambience via the Oda system that wouldn’t have otherwise been possible. Ka Baird performed from her studio in Brooklyn, and invited me to get comfortable, “perhaps do some stretching”. On starting her voice in stereo felt proximate and physical, the somatic elements of her performances tangible and real. She talked about how it felt very intimate, and I emailed her to ask her what it was like to perform in these circumstances. “It was like an intimate phone call in the dark, like whispering into the listener’s ears" she wrote back, "the line seems very direct and personal". She was conscious of "transmitting direct into one’s private space, where the receiver could be in the bath for all I know, or naked on the couch, or ideally at least in some state of high comfort".

While the performance obviously remained disembodied in some ways, she says she was struck by being able to control exactly what the audience was hearing, since they were all listening through the same equipment (this is not true for other livestreams). The high sound quality coupled with the intimacy and comfort of home seemed to allow for deeper listening – whereas in a normal live show, the sonic impact on a listener would have depended on where in a venue they chose to stand.

It’s the intimacy of the at-homeness that also appealed to Phil Elverum, aka Mount Eerie, who has passed on other live streams – aside from other issues, he says: "The amount of Zoom in my life – I’m a parent of a school aged kid – makes the idea of performing to my computer camera totally unappealing."

He doesn’t see Oda as playing shows as such, but rather as a direct home-to-home transmission. He’s known Oda’s founder Nick Dangerfield since about 2009. "When Nick first started talking to me about it many years ago, this idea of a direct transmission from my home into a listener’s home that was basically always on, or always available to be turned on, it seemed totally novel and crazy and interesting: a microphone, and many hundreds or thousands of miles away, the speaker. It opened up everything. It also seemed a little nuts. For people to have this speaker in their home that could potentially start emitting a transmission at any time, and for them to willingly sign up for it was so cool and strange."

For his set during preview week he performed in the music room of his house, which is also his bedroom. He says he "stumbled around live creating this morphing idea of music" with tape decks, an organ and a guitar, and says the experience raised questions and possibilities – about what it means to soundtrack someone’s home, but crucially, opened up what he said was very fertile and high risk creative territory for him. He doesn’t see Oda as a livestream, but as something entirely new. "In this new territory where I’m imagining trying weird new things, it will be extra scary. This scariness makes it seem valuable from an artistic angle, as well as just a personal growth angle. It’s like leaping into an unknown."

For artists, Oda doesn’t just offer new performance possibilities, but also, crucially, a new income stream that isn’t dependent on people being able to safely gather together. It also means that artists who struggle with the demands of touring, who are elderly or with health restrictions not often covered by DIY venues, are no longer excluded from performing live, or generating a live income. This not only opens up an income stream for those who are housebound or find touring difficult, but also extends possibilities for those with hefty pieces of equipment like bulky synthesizers.

From an audience perspective, Oda comes with the promise of hearing artists and musicians there was previously no hope of seeing live, while also offering a previously inaccessible chunk of income to those individuals.

It’s encouraging to hear about a project that is thinking intelligently about ways to remake the relationship between audience and artist, and the ways technology mediates this relationship, but which is also based on building a sustainable economy. Oda is about the intimacy of a performance, but also income streams.

From an audience perspective, Oda is trying to get us off our screens and into a comfortable state where we can listen. For artists it offers an income and creative possibilities that just don’t currently exist.

When Oda launches on 6th October, it will initially be run on US East Coast and West Coat time zones, and programming for UK and Japanese specific time zones will come later. However, Oda says shows will happen at times that work for as many regions as possible (eg, the sunset shows in New York happen around closing time in the UK, and weekend shows will have daytime elements). I hadn’t anticipated the unexpected element of these transmissions, until one evening, the music I was playing through Oda’s aux connection from my phone, switched unexpectedly to ambient sounds and water, and then soft meditative music and speech. It was a sunset show from Laraaji, broadcast from New York at my bedtime. It may have been his soothing music, but it may have also been the sound – the shift in quality and texture in the audio from my phone and the live stream is notable, and it has the desired effect of settling me and my partner in on the sofa. Both of us noticeably relaxed, as it sounded like Laraaji was actually in the room.

When the day after the surprise Laraaji show, my partner messaged to ask how he could switch Tompkins Square Park on again, I realised that we have become quite attached to the speakers, and that compared to the events we’ve watched on my laptop, we have sat and listened properly to Oda’s transmissions. When I got back the tinkle of the ice cream van in Tompkins Square Park passed across my fireplace. In a few months, this ice cream van might be the sound of a cellist rehearsing, or the circuits warming up on a synth. Over the course of a month I’ve gotten used to these two wooden squares, a window into other music rooms and studios, and since the preview week finished, I’ve kept the window open on Tompkins Square Park, too.

You can find out more about Oda via their website, Instagram and Twitter. This editorial is part of a commercial partnership between Oda and The Quietus