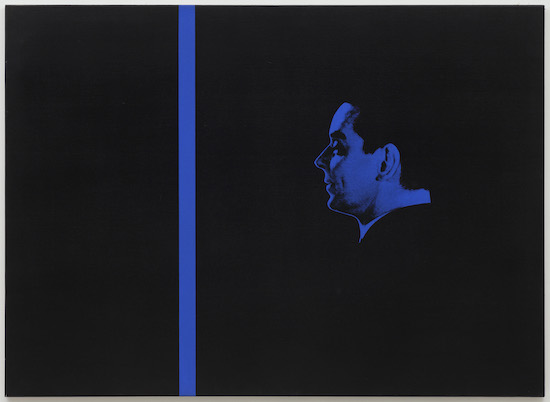

John Stezaker, Untitled, 1978–9. Silkscreen on canvas 48 1/8 in. (122 x 167.5 cm)

In 1977, on the occasion of his solo show at The Photographers Gallery, John Stezaker chose to use the platform provided to him by the exhibition catalogue to publish a comprehensive analysis of his working methods. “Collage”, he declared in this lengthy essay titled ‘Fragments’, “can only exist in what Walter Benjamin called the age of mechanical reproduction”. The provocative nature of this declaration stemmed from the fact that it attributed to collage a defined historical context and specific material conditions, suggesting that collage is a coherent artistic mode reliant by default on technological means of image production. The argument complied with the well-established historical claim that collage had transitioned from a certain category of handicrafts, or pastime activities largely associated with the domestic realm, such as scrapbook-making, silhouette cutting, shellwork and other playful creative practices, into the realm of modern art with the emergence of a new technological era, in which our relationship to images became essentially different from the one that preceded it in the first part of the nineteenth century. However, Stezaker’s assertion must also be considered in relation to the particular moment of its pronouncement. The question that Stezaker’s work seems to have been raising above all was whether by 1977 collage was still a relevant and effective artistic process, and, if so, whether it should comply with the same set of technical conditions assigned to it nearly 70 years earlier (by the likes of Pablo Picasso, Jean Arp, Max Ernst, Kurt Schwitters, Hannah Höch and other pioneeringpractitioners), despite the range of new media that had since emerged from and around it.

Indeed, to a large extent this question concerns the implications of the new techniques of image editing, manipulation and reproduction that were being introduced to art, as well as to other modes of visual communication, in the 1970s: forms and media that no longer juxtaposed images as separate units or fragments but that rendered them in a seemingly molecular, seamless manner. Thus, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, while digital images had not yet been incorporated into the popular language of visual culture, collage was standing trial for its ability to remain an effective, relevant and meaningful medium that corresponded to the issues of the hour. And while the principles of cut and paste flourished in other industries – from advertising to the DIYculture of VHS and cassette tape recordings in every home, all the way to the new tendencies in design, architecture and theory under the banner of ‘postmodernism’ – the ideological and theoretical backbone of collage as a category in its own right was gradually becoming a remnant of the past in the eyes of artists such as those affiliated with the Pictures Generation in the United States, as well as in the eyes of their academic counterparts, the critics, curators and art historians associated with the then newly established journal October.

Stezaker was intrigued by the premise of his colleagues in New York

but felt encouraged to explore the impasse from within. He concentrated his exploration on collage’s primary attribute: the juxtaposition of two image fragments. Restricting himself to a limited range of photographic materials and a minimal set of essential actions, Stezaker’s arsenal of image sources included three categories: first, photographic postcards, carefully selected according to their production date, mostly from the first decades of the twentieth century and primarily those in colour. Second, black-and-white photographic film-still photographs, though here too he was particular about the date and the context of the images, focusing almost entirely on film stills for foreign language B-movies (low-budget films screened after the primary film in a double feature), and always from the 1940s. Finally, he began incorporating a third category of photographs. These were black-and white headshots of actors from the 1940s and 1950s, both well-known and lesser-known, that were used for similar promotional purposes to the film stills themselves. At first, these portraits were too costly for Stezaker to buy in bulk – in 1980 he owned fewer than 100 film-still and headshot photographs – and he was cautious about cutting any of them. With time, however, it became clear these materials had little future as collectibles (except for those showing very famous actors) and their prices began to drop, until eventually he could afford to acquire entire archives comprising thousands of photographs. This specific range of materials represented a mere token of the wider category of mechanically reproduced images which Stezaker perceived as mass produced, serial, generic and inherently imbued with a certain mobility, whether through time (the film as a moving image) or space (the postcard as an image that literally travels), in a way that did not exist before the mid-nineteenth century. One can add to these attributes of the mechanically reproduced image that it is also profoundly invested in the notion of scale. As postcards tend to miniaturise the monumental, so films tend to make the insignificant and the mundane gigantic. Stezaker was now focusing on found photographic materials produced for only a brief period shortly before he was born: images that felt familiar and natural to him but which all the same depicted a moment in time – the golden age of Hollywood – that was inherently foreign to his experience of the world.

The question remained as to how Stezaker was to manipulate these pictures to demonstrate their role within the economy of the mass-produced image; their liminal state as photographic media that were facing extinction; and their possible role in the present and future economy of visual culture as archival materials. Thus, around the same period, in addition to the strict adherence to predetermined categories, the manner in which these materials were employed in Stezaker’s work also became subject to a set of rules or guidelines, according to which he submitted one or more of the pictures to a straightforward technical procedure that interfered with their original appearance. Such gestures, whether the introduction of a particular type of cut or the combination of particular kinds of photographs, lie at the origin of Stezaker’s numerous cycles of mature collage works,and they emphasise the serial nature that is inherent to postcards and film stills alike. Accordingly, most of the photo collages produced by Stezaker from 1977 onwards take a clearly defined form. This might be a diagonal cut that runs across the composition in order to join

two photographs, as in his cycle of Marriage collages (1988–present), where male and female actor portraits are combined in a disturbing, grotesque or humorous manner. Or it could be the act of placing a postcard on top of a film-still photograph, as in his Inserts and Mask series (1977–present and 1982–present, respectively), where one image functions simultaneously as a façade and as a window onto a second, background image. Further still, the gesture could be as modest as the turning of a picture upside down, as in the Unassisted Readymades (1977–present), where a simple change of orientation results in complete disorientation of the composition. Whatever the intervention, it serves to draw attention to details that the viewer would not otherwise be likely to deem important; to illuminate certain similarities or differences between two fragments; to examine the common characteristics of a picture; and most importantly and without exception, to disturb the coherent narrative one expects from a pictorial work by its subversion or substitution with another. It is partly for this reason that Stezaker largely avoided well-known films, actors or postcards of renowned monumental sites, focusing instead on stills that cannot be pinned down exactly, or postcards that depict peripheral monuments or provincial natural sites, like caves and waterfalls in rural places. These photographic materials possess a familiar, generic appearance, and yet few observers wouldactually recognise their precise subjects. The resemblance to famous Hollywoodactors or great monumental destinations serves as bait to lure the viewer closer to the picture, perhaps to identify the original subject or to explain the connection between the two unrelated pictures in the collage. However, the impossibility of solving either one of these riddles causes one to confront the very condition of the picture’s visibility and to simultaneously be freed from the burden of specific information.

The sets of rules or preconceived conditions that Stezaker established as the premise of his work more strictly from 1977 onwards have also come to inform the choice of content in the images to which the materials and procedures apply, as well as the choice of theoretical terms that Stezaker has employed to delineate his practice. Thus, Stezaker’s strategy applies to the nature of the photographic materials that he uses, their subjects, the consistent relationship between the composing elements, and the commitment to a particular terminology throughout different series of works. It is tempting to suggest on the basis of these rules that one could replicate the recipe or prescription

for the production of a Stezaker collage, at least in theory, and that this premise reduces his work to a mere formula. Rather, however, it reflects something of his approach to collage as an activity inherently tied to the logic of seriality and reproduction, and whose creative aspect comes into expression precisely thanks to the specific conditions of each

composition and not to the rules that dictate its production method.

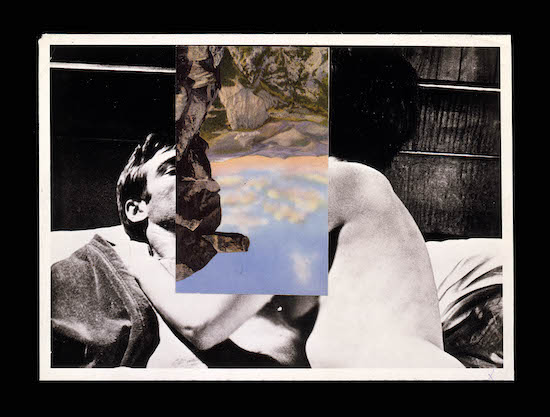

Mask (1982) Postcard n film still photograph, 19 x 24cm

Mask from 1982 offers a good case in point as the first work that Stezaker deemed successful in a large ongoing series of the same name. The Masks take the form of actors’ headshot portraits interrupted by a postcard serving to conceal their face. In this particular instance, Stezaker chose to replace the countenance of a young actress with a postcard of a stone bridge spanning a river, leaving her shoulders and chest visible to the viewer. In front of the figure hangs a rope ladder, suggesting that she is an acrobat or a performer of some kind. The placement of her body and face within the borders of the rope also encourages a reading of the portrait as contained within the frames of a film strip, although the lack of movement imposed by the photographic

medium also indicates a certain resistance to the fluency and speed that the moving image requires in order to come to life. The postcard that conceals the actress’s face can be read both literally and metaphorically: a double-arched stone bridge crossing a river resembles a set of eyes; a pile of rocks can be interpreted as a nose and a mouth; and a small canoe that approaches the viewer from a distance marks the exact position where the pupil of one of her eyes might be. At the bottom of the postcard itself, a text completes the touristic-cinematic reference: ‘Shooting the Rapids, Killarny’. Although Stezaker tends to emphasise the metaphorical aspect of his works, Mask seems to be operating also

metonymically, completing the actress’s facial traits with a continuum of forms that traces her very features – or almost so. At once highly calculated and accurate but also disturbingly misplaced, the mask is grotesque, confusing and full of humour. As Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith indicated in his analysis of Stezaker’s Masks that make use of caves and other rock formations:

The immediate visual impression given by these literally craggy faces, collapsed features, streaming visages and hollowed-out skulls is one thatmay be broadly classified as grotesque, a category usually defined art-historically in terms of comically or repulsively distorted composition and the fantastical interweaving of forms drawn from incongruous sources. As if to underline this categorisation, the preponderance of caves among the postcards chosen for many of the… Masks slyly invokes the etymological origins of the term ‘grotesque’, which derives from the same Latin root as‘grotto’, meaning a small cave or hollow.

The symbolism of the Masks corresponds also with the metaphoric order of Surrealist collage, whereby body organs are replaced by inanimate objects, for example, while the straight-lined edges that separate the postcard from the photograph relate to the metonymic order that characterised early Cubist collages. A clash of pictorial and linguistic traditions is thus brought to the fore. But the Mask series is only one expression of Stezaker’s earlier cycle of postcard and film-still collages, which he identifies more broadly as Inserts: namely, works that include the placement of a postcard on top of a larger film-still photograph. For Stezaker, however, inserts imply a more complicated spatial intervention. The postcard is not simply placed on top of a

larger photograph in order to conceal part of it, nor is it positioned by its side as a comparison to it. Instead, the insert invades the photograph with which it interacts, confusing the relationship of the two images in a number of ways: formally, by implying how the outline of what it conceals might have looked; conceptually, by encouraging the viewer to relate the two images to each other in an associative manner; chronologically, by including colour postcards that are nevertheless older than the black-and-white film stills on which they are arranged; and finally, by confusing the relationship between the postcard and the film still in spatial terms by functioning as both a window to a reality that lies behind the covered image and as a mask that conceals it.

John Stezaker: At the Edge of Pictures is published by Koenig Books. The exhibition, At the Edge of Pictures: John Stezaker, Works 1975–1990, is at Luxembourg & Co.,London, from 2 October–5 December 2020