Photos by Mariana Reyes

In the 1990s, when Eblis Álvarez was studying in the Colombian capital of Bogotá, cumbia music was mostly associated with folkloric gatherings and traditional holidays. “It was seen as this music that was intended just for Christmas,” he remembers. “But me and my friends listened to it as a part of our daily lives and found something special.” Away from cumbia’s traditional home region of the coast, their tastes were somewhat unusual – this was before cumbia underwent a fashionable 21st century revival. “As Latin Americans we were exposed to all kinds of global styles, global hits on the radio, some of them were good, some of them were bad, and I was also a metalhead,” he recalls. “In the circles I was involved in, the music conservatory, the jazz scene and the rock scene, no one would take tropical music seriously. On the coast it was a little different, there were orchestras and a whole tradition, but not in Bogotá.” In 1999, they began Ensamble Polifónico Vallenato, a project that focussed solely on tropical accordion music and cumbia. “Which was very weird in those days.”

The traditional music and dance of Colombia is as varied as the country’s geography. From the Caribbean and Pacific coasts come respective forms of music from large African-descendant communities – the reggae-influenced champeta music on the east and the rhythmic currulao of the west, to name just two. In the mountainous central Andean region, there is bambuco, an old style with its roots in Basque and Spanish folk, as well as the romantic guabina. The Eastern plains of Orinoquía are home to harp-led joropo music, which is also popular in Venezuela and not dissimilar to Flamenco. The coasts are also the birthplace of big band porro music, influenced by European brass ensembles, as well as the hugely popular vallenato, popularised by Spanish settlers. At different points in the 20th century, New York Salsa music, reggae and rock en español has also had significant influence. There is a reason the country’s tourist board have at times employed the slogan ‘Land Of A Thousand Rhythms’.

It is cumbia music, however, that is the best known internationally. “It’s kind of our national music,” Álvarez says. “It changed from bambuco to cumbia in the ‘60s and ‘70s. When I grew up it was in the background as the symbol of Colombian music.” His father was from the particularly musically-rich coast. “He’d play not just cumbia, but tropical music, montuno from the Caribbean and Colombian salsa which is influenced by New York. It was a tropical universe, and cumbia was among it but not very high profile, there were no artists focussing on it, it was just our folk music.” Álvarez estimates it’s been present as a framework in “around 70%” of his vast discography. For his new album Cumbia Siglo XXI, however, for the first time the genre becomes the focal point. It’s a record of immense energy, transforming traditional folkloric rhythms into something ultra-modern with the help of blasting electronics and incisive, politicised song writing.

At first, Álvarez laughs when asked how he would explain cumbia music as if to someone who’s never heard it before. “That’s an unanswerable question!” he jokes. “Cumbia has too many approaches, and then there’s the cumbia of Mexico, Argentina, Peru… all of them are emblematic styles [of those nations].” There are, however, some bare essentials. “The very, very most important thing is the lamador,” he says, “which is a drum which strikes on the second and fourth beats. This is the thing that cannot be removed from cumbia. Then in Colombian cumbia we have certain specific references. We use the guacharaca, which is like a small, wooden-made guiro, and then depending on the region there’s accordion cumbia, a full band cumbia, cumbia played only on African tambores….”

It is the lamador that has been of most fascination for Álvarez across his career, that intrinsic beat at the genre’s very core. “That was always the key thing for me,” he says. “The thing that connects cumbia to the world. The world is very into binary rock and binary funk, and cumbia is the same. I think this is the reason why cumbia has kicked on a bit more [internationally] than salsa, or more complicated Colombian music. I discovered this thing about the common patterns in music all over the world, something that marked the whole story of modern music. I found there was a common pattern that could be Latin America’s way of existing with its own identity.”

Reducing cumbia to what he describes as “pure music, just a relationship between harmony and rhythm which is not put into the cultural stream of stuff,” and used the structure as “a channel of communication, a way for me to communicate whatever abstract ideas.” He compares it to “the way rock music’s generic format – the drum set, the bass, the attitude, the number of people playing – has been a way to channel different abstract ideas and philosophies for the last 60 or 70 years in mainstream art. It can be something very avant-garde or something very cheesy; it’s still the same format.”

Álvarez , who teaches music technology at the Universidad Javeriana, always approaches his music with this academic bent. “It’s more preparation than music!” he says. Take Meridian Brothers’ last album Donde Estas Maria, for example, a beautiful and largely acoustic album that was an exploration of what he calls “the global song, the music that came out of the globalisation of music, especially by The Beatles, and how the whole world copied their attitudes. I researched this style and found it Colombia, and in Brazil and in Mexico, and I thought ‘let’s make a record of global song’.”

This time around, he based his research around the discography of a crucial independent label called Machuca. Based in Baranquilla near the Caribbean coast, the music they released in the late ’70s and early ’80s took a revolutionary stance on cumbia and tropical music. To Álvarez they were cross-generational kindred spirits. “Those guys were pretty revolutionary,” he says. “It wasn’t famous, just a small label, but it was a golden time for Colombian music. They were doing fresh stuff all the way.” Cumbia Siglo XX, which translates as 20th Century Cumbia, were the most progressive group of all. Their music was mainly composed for the city’s world-famous carnival – claimed to be the second-largest on earth after Rio de Janeiro – and they saw limited success outside of their home region, but nevertheless they were pushing boundaries. “They went with guitar first, and there’s not too much guitar in Colombian music, along with the normal lamador,” Álvarez enthuses. “They were combining all kinds of music, there were cumbia rhythms combined it with montunos and pujas, changed the tempos. It was progressive.”

Meridian Brothers’ new album is called Cumbia Siglo XXI, placing it as the direct successor to the spirit of Machuca records, doing with synthesisers what his predecessors did with guitars. “Every record I could find on the label was like ‘woah man, these guys are really far out,’ so when I decided to make [my new album] I made a playlist of all their music, and I said ‘I will have this energy through the whole record’. I began to use the songs as role models, their psychological attitude towards sound and music.” At the same time as his exploration of Machuca, Álvarez was finally making headway with a longstanding attempt to get an electronic interpretation of traditional Colombian music off the ground, inspired by Kraftwerk, “the first ones who got complete machine-made music into the domain of pop music,” as he describes them.

“I’m a musician that has a very weird relationship with electronic music,” Álvarez continues. “At the end of the ’90s I just hated keyboards, I liked acoustic music, but then when I went to study composition I discovered algorithmic synthesis, a way to program synthetic generated sounds within an algorithm. How you can just put sounds one on top of the other, but without any cultural context. This is again what I called ‘pure music’, music that’s still not in the sphere of public listening. I just got very into programming and computers and synthesis software, but I didn’t do anything with that because I didn’t know how to take that and put it into Colombian culture. It wasn’t loud enough, or punchy enough, but eventually I managed to do it, and it was Cumbia Siglo XXI.”

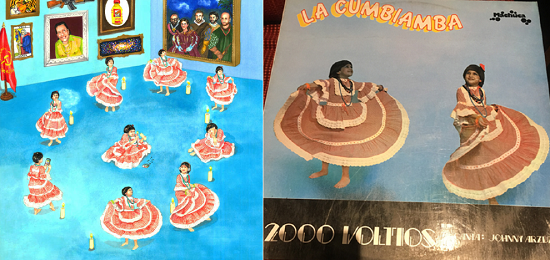

The cover for Meridian Brothers’ new album is a direct reference to another of the key releases on Machuca, La Cumbiamba by a band called 2000 Voltios. On the front of that record there are two girls dancing in traditional cumbia dress against a vivid blue background, with the same girls but now a group of nine, and the same blue, reappearing on the cover of Cumbia Siglo XXI. Just as the record’s music updates Machuca’s modernised cumbia, so too are the girls brought into the present. “The artwork is by Glenda Torrado, a Colombian artist who lives in Mexico. When the idea of Cumbia Siglo XXI came to me I thought of that cover by 2000 Voltios. We talked about ‘let’s make it the same colour and the same girls, but let’s give them a 21st century attitude. One’s looking at her mobile phone, one is smoking, another is sleeping, one is listening to something else on her headphones, no one is paying attention to the cumbia ritual, it’s all individuality.”

On the walls of the room the girls are dancing in are a number of paintings, a motif in Torrado’s art, as well as a flag and a mounted gun. All of them bear some relation to either a lyric on the album or its wider themes. “There’s a tiger taken from one of the album covers of Cumbia Siglo XX, the Milky Way is because one of the songs is about the Milky Way, and there is also a portrait of Diomedes Díaz, a very famous singer who was very controversial because he killed a girl and it was a huge scandal here in Colombia.” One of the paintings depicts the Meridian Brothers themselves, but clothed as if renaissance-era European aristocrats. It recalls Colombia’s dark colonial past; as Álvarez put it in an extended essay about the artwork, “that supposed source of civilization and also of warlike oppression, of bloody conquest [combined] with tacky careerism.”

Herein lies the real power of Cumbia Siglo XXI, beyond even its remarkable sonic marriage between the spirits of Kraftwerk and Machuca records. Through the songs themselves – which bear titles like ‘Cumbia de la igualdad’ (‘Equality Cumbia’), ‘Cumbia totalitaria’ (‘Totalitarian Cumbia’) and ‘Cumbia de los proletarios’ (‘Cumbia Of The Proletariat’) – Álvarez offers a deft dissection of the wider culture that surrounds his ultra-modern cumbia. “I’m not very active on social networks, but I look at them a lot to analyse what’s going on,” he says. “I’m not a philosopher or anything, this is just my opinion, but to me it’s absurd. The more people are moral and ethical in the name of ‘freedom’, the more they just get into fights, the more aggressive they get. These are some of the themes of the album, the absurd fight for freedom in the ideologies of the internet, something people don’t really think through.

“Over-communication and speedy communication doesn’t lead the brain and the conscience to reflect on itself,” he continues. “You get drowned by information and data and ethics that are changing everyday. You subscribe to all these news outlets and you just get confused. I think this excess of information and the lack of communication with our own self starts altering information on the outside. On the other hand, if there’s not enough information human beings get too self-reflective and enclosed. For me it has to be a balance between the outer and the inner. With the balance culture gets fertile. I think that happened a bit in the ’60s and the ’70s, and other points in the history of human kind, where there was a balance between what the individual gets in terms of information, and what the individual thinks on its own too, in order to be fertile and create new stuff, which for me is the main purpose of human beings, to create things.”

When it comes to Cumbia Siglo XXI, the very act of its creation is a counter to toxic streams of over-communication. By revitalising music that represents a distinctly Colombian identity, he hopes to battle what he sees as a worldwide homogenisation of culture. “In my opinion globalisation is this fake union of humanity that’s being pushed through governments, dogmas and ideologies,” he says. “It’s been said that we’re going to reach a new era of peace with their ideologies, but we’re not really united because it’s the institutions that are the ones joining us together and all I’m seeing is people fighting with each other. The damage that globalisation does is very easy to see here in Colombia; our economies are being destroyed; African economies are being destroyed. So if we make different stuff within our cultures, it will be more difficult for these powers to dominate us. The more information we have, the more information they have to erase and conquer. For me, identity is not to say something like ‘my culture is better than another’, it’s not patriotism. It’s a defence, the creation of more and more lines of information so the system cannot conquer it. Always, in every city in the world, there’s a new group of people doing new art, doing new culture that the powers have to conquer all over again."