For a while, in the late 1930s, the Left Book Club had a membership of 57,000 subscribers. Founded in 1936 by publisher Victor Gollancz with the avowed aim to "help in the struggle for world peace and against fascism", the Club that hoped to break even at 2,500 subs soon found itself becoming a mass movement, organising annual rallies, and was widely credited with aiding the Labour Party’s electoral victory after the war.

Many in the new government had published books distributed via the Club. But Labour’s victory in 1945 proved to be the beginning of the end for the Left Book Club and by 1948 it had ceased publication. Until, nearly seventy years later, it was revised.

As the new Left Book Club prepares to celebrate its fifth birthday, tQ spoke to the new Club’s manager David Castle, programme manager Melanie Patrick, and communications coordinator Brekhna Aftab about the past, present, and future of radical publishing

How did you first hear about the original Left Book Club?

That’s hard to answer! I’ve always worked in publishing, and the world of socialist and left publishing is pretty small. The history is just sitting on the shelves around you. The old red hardbacks from the 1930s and 1940s are immediately recognisable and the story behind them is fascinating. The club was set up by Victor Gollancz as an attempt to bring left ideas into the mainstream, specifically to oppose fascism and inequality. It became this popular mass movement for political education. Gollancz set out to appeal to a popular audience, and he succeeded – he had 57,000 members. Some of the books were quite challenging, but people read them because when you’re living through a crisis, whether it’s 1936 or 2020, these ideas offer you hope that change is within our reach. Being part of a club also helps you feel part of something bigger than just yourself.

What was it about the story behind the Club that drew you to it and made you want to revive it? And how did that come about?

Partly it was the scale of the original Left Book Club: the broad base of its membership, the transformative effect of its publishing on British political culture and on the epoch-making policies of the post-war Labour government. It’s reach was formidable – it was from a time when left wing publishing was a tiny affair and most books were expensive, but it developed a direct, dynamic relationship with members offering cutting edge new books at affordable prices and bypassing traditional publishing. At a time when high street bookselling is in crisis and Amazon monopolises online sales, this direct relationship with readers is again very important.

The decision to revive the LBC came about in summer 2014 when a group of activists, authors, trade unionists and publishers met in a pub in London, brought together by historian Neil Faulkner and retired teacher Jan Woolf. At an early stage we got statements supporting the relaunch of the LBC from many prominent figures including Jeremy Corbyn and Noam Chomsky which was very helpful in attracting our first members.

Your past books have been selected from a number of different traditions – socialism, anarchism, feminism, populism, etc. – how do you define a "left" book? What are your selection criteria?

Our authors do come from many political perspectives, as you suggest, and they do not all agree with each other on everything. But all the books criticise power from below, or they look at ways to transform our society for the better, in ways that are more just, equitable and environmentally sustainable. Some books are more personal, and some more analytical, but we try to ensure that all books engage with issues at the forefront of current political consciousness. The books are chosen by a panel of authors, activists and people working within the book trade.

On the LBC website you talk a little bit about the original club’s role in the Labour victory in 1945. The revived club has the support of Jeremy Corbyn. Can you talk a little bit about the relationship of the Club with the Labour Party, and how you see that relationship going forward in the post-Corbyn era?

We are not aligned to any one political party, but as an organisation that champions socialism and anti-capitalism we supported Corybn’s leadership and the potential for real change that it presented. We are happy to work with the Labour Party any way we can to support political education in our communities. We’re always looking for people to start new reading groups, so if you’re interested, get in touch. We’ve also worked with The World Transformed to provide a reading group guide.

Having said that, our books are chosen to represent a range of views on the left, and we know our membership is the same. We wouldn’t want it any other way! In the 30s although Gollancz himself was close to the communist party, he was very clear that to create a popular movement against fascism, he wanted to bring in those from the centre. In the end, the Labour Party became a home for many Left Book Club authors. Clement Attlee was a Left Book Club author, as were eight members of his original cabinet.

Are there any ways in which you see your mission diverging from the original Left Book Club of the 30s and 40s?

In many ways, we are honouring the legacy of the original LBC and its spirit of collective political education. While the political context today is different, we are going through a severe crisis of capitalism and the original mission of the LBC is as relevant as ever. Bleak times like this offer the opportunity to imagine and fight for better alternatives. I think one point to note is that we are really trying to focus on what unites the left, rather than getting swept away in factional debates. We know that C.L.R. James, for example, had quite a complicated relationship to the original LBC because of his diverging Trotskyist views. Something like this would never stop us from including such a crucial writer on our list, in fact it was really important to us that we published The Black Jacobins and circulated this ground-breaking book to our members.

To many modern readers, the name "Gollancz" might be more associated with science fiction publishing than radical books. But do you think there might be a connection between the two?

Interesting question! I’m sure others will have much more to say about this, but in my view there is certainly a connection between radical politics and science-fiction. We can see that quite clearly in the works of Ursula Le Guin or Octavia Butler. That’s not to say that there isn’t also conservative or reactionary science-fiction being published, but the genre gives us the space to view things that we might consider normal as unfamiliar or strange, pushing us to question the status quo and imagine alternatives in a more expansive way.

What plans do you have for the future of the Left Book Club?

I think one thing we speak about a lot as a team is the importance of ensuring continuity of the project. We’ve seen a lot of brilliant initiatives fall apart when there aren’t structures in place that persist, even if those organising the project at the time were to move on to other things. When you have a working system in place for selecting the books, distributing them to members and helping create reading groups, the LBC becomes a bigger thing than the people running it and that’s what we want it to be. Our plans for the future centre on using the technology available to build these systems, ensuring that our books and reading groups are accessible to everyone, wherever they are based. The past few months have shown us that the world can change fast, and the damage inflicted by capitalism is more obvious than ever. People want to imagine new ways of organising society, and in partnership with other publishers we want to help popularise the ideas that can bring about a better future.

Could you choose for us a small selection of LBC books to give people a sense of the sort of thing they might get for their subscription?

Beyond the Fragments: Feminism and the Making of Socialism

by Sheila Rowbotham, Lynne Segal and Hilary Wainwright

I was hugely influenced by Beyond the Fragments when I first read it in the late 1990s, and I felt excited and privileged to be able to issue it to LBC members. Beyond the Fragments brought many lessons learnt in the feminist movement to socialist politics – in particular that the personal is political, and that the way we practice our politics should prefigure the kind of society we want to build, and it sharply criticised the hierarchical top-down forms of organising found in the Socialist Workers Party, Communist Party and other Leninist parties.

These ideas have all grown in influence since the book was first published in 1979. What is now less recognised is a theme which runs powerfully throughout the whole book: that identity is relational and political practice is transformative on the personal level as well as a structural one. Personal identity, rather than being immutably defined by the forms of oppression one has experienced, or fixed by race, gender, sexuality, class and other social markers, is transformed through inter-personal relationships to enable new forms of consciousness and collective identity, and it is these processes of change and growth which allow for a broad-based radical movement to emerge – enabling us to get ‘beyond the fragments’ of identity politics, single issue campaigns and sectarian revolutionary parties.

The book is also a window into the fascinating world of radical politics in the 1970s, before the revolutionary imagination ignited in May 1968 became foreclosed by decades of neoliberalism.

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth

Doughnut Economics is a wonderfully clear and persuasive outline for a socially just, sustainable economy. Unrestrained capitalism has led to spiralling inequality and the approach of environmental catastrophe. Four decades of governments across the world being guided by neoliberal economists has meant that people are coming to replicate that caricature of humanity described by economists as economic man – individualistic, selfish, insatiable. Instead, we need an economics which encourages the innate human tendencies towards co-operation, sharing and mutual aid.

Kate Raworth argues that economists should be like gardeners tending to and shaping the economy as it evolves, recognising environmental limits and encouraging regeneration rather than extraction and waste, and aiming to re-distribute wealth (including land) as well as income to reduce inequality. It is all crystallised in the image of the doughnut (the American doughnut, with a hole in the middle).

We can’t have too little, get too near the centre, for everyone’s basic human needs must be met – not just physical needs like food and water, but also social needs like education and political voice. But we can’t stretch too far out, beyond the limits of the doughnut, or we go beyond the ecological ceiling of what our planet makes possible. While the implications of the book are truly radical, it is all expressed in such measured tones that it is hard to see how anyone could disagree, and indeed the book was a Financial Times book of the year and was well reviewed across the mainstream press. But it is one thing to know what needs to be done, and another to dispossess the wealthy and compel the powerful to implement the changes that need to be made.

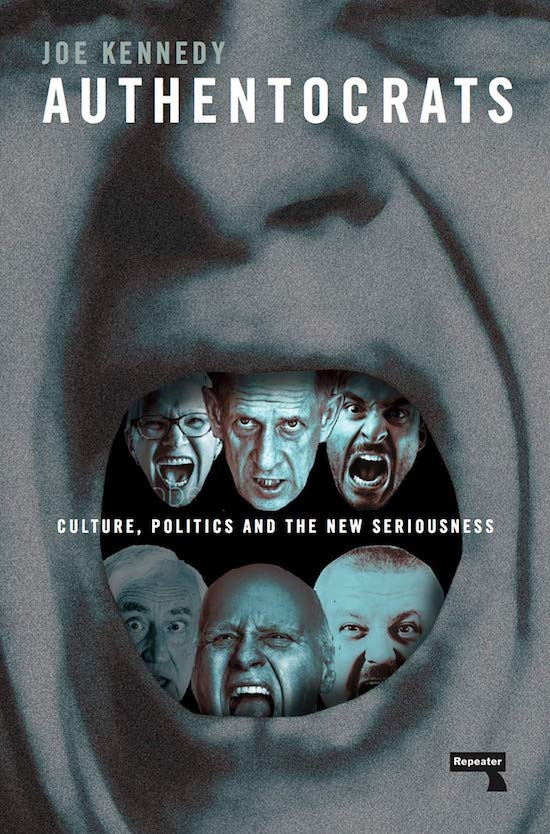

Authentocrats: Culture, Politics and the New Seriousness

by Joe Kennedy

This is a lively and provocative polemic about class and culture in the UK. It’s a great explanation of the gradual hollowing out of class politics under Blair eventually led to the Brexit vote, as well as a good insight into ways of thinking about ‘Englishness’ more generally. Kennedy is an angry and very entertaining writer.

The main thrust of the argument is that most politicians and prominent journalists are privileged and often privately educated, so they have no idea how most people in the UK live. Desperate attempts by liberal politicians to appeal to an imaginary centre ground — populated by ‘real people’ with ‘legitimate concerns’ — usually end up pandering to the same racism and dangerous nationalism that we’ve seen from Trump. Beginning the book with Owen Smith’s ill-fated attempt to drink a cappuccino, Kennedy moves on to a wide analysis of TV, film and music, and offers a scathing take-down of the politics of Generation X.

Returning to Reims

by Didier Eribon

This book was a huge hit in France and elsewhere in Europe, but is not so well-known in the UK, so it was great to add it to our list as it’s helped bring it to a wider audience. It’s a remarkably personal story, and very moving. It’s both a memoir and an exploration of ideas around identity and belonging. Didier Eribon tells the story of his upbringing as a gay young man in provincial France. Returning to his childhood home as an adult, 30 years later, he reflects on what it means to be born working-class and then leave that class. He explores why so many working class people in France are turning away from Communism to the far right, which he links to neoliberalism, the rise of individualism, and a loss of class consciousness. A complex, poignant and beautifully-written book.

The Black Jacobins

by C.L.R. James

If someone asked me to list the most important books for anyone interested in left politics to read, The Black Jacobins would absolutely be on that list. This is a masterful account of the Haitian Revolution, which was the first successful slave revolt in history and defeated the greatest colonial powers of the time. James commented that he wanted to overturn the portrayal of slaves as passive victims of history, instead highlighting their agency and showing how they were the true protagonists of the revolution – that’s something many writers could learn from even today.

It’s also a very important study of the links between the transatlantic slave trade and the rise of capitalism in Europe. This book doesn’t read like an academic history, but is a truly riveting narrative interweaving philosophy and political analysis while capturing the political intrigue and drama of a revolution.

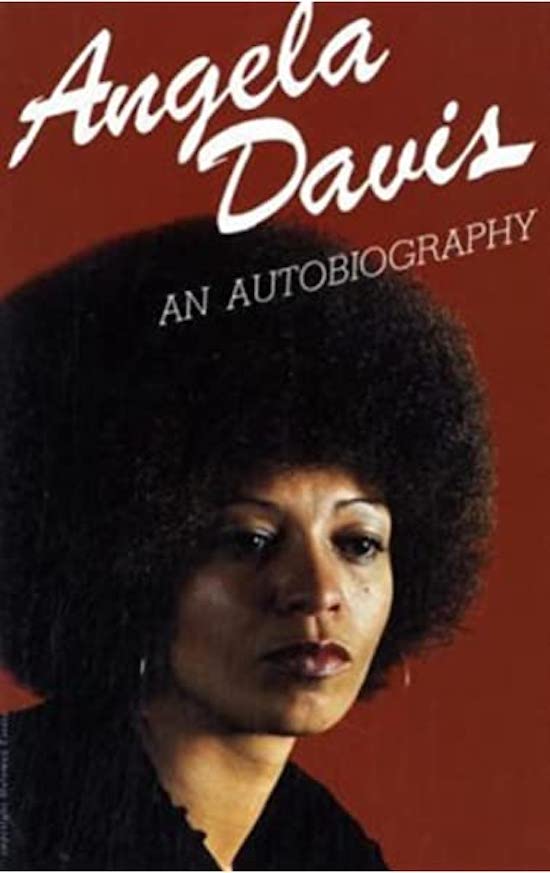

An Autobiography

by Angela Davis

We felt so lucky to have this book on our list. Written in her late twenties, Angela Davis utilises her autobiography to highlight the social forces and movements that shaped her life, providing a compelling first-hand account of radical politics in the 1960s and 70s.

In the introduction to the new edition of the book, Angela Davis discusses the complexity of writing about the dialectic between the personal and political, which I think manifests throughout the book in a very honest and interesting way. I also love that Toni Morrison persuaded her to write the book – I think knowing that it is the product of a collaboration between two such brilliant writers and friends makes it a very special work.

To find out more about the LBC and purchase a subscription, visit the Left Book Club website here