Uniform. Photo: Ebru Yildiz

So-called “creatives” waste giant swathes of our lives trying to find new ways to articulate universal experiences. As soldiers in the war of expression we come armed to the teeth with hubris. Our feelings run so much deeper than those of civilians who rely on our work to escape from or make sense of their excruciatingly basic lives. We are artists. Art is sacred. Bow the fuck down. Tremble!

Of course, this sentiment is by and large bullshit. What I am trying to say through a metric ton of overwrought hyperbole is: We sure think we’re special. There are exceptions, but generally even the humblest among us have a bug up their ass about their work carrying a degree of importance. Hell, maybe it does? It’s a big world out there and I understand the appeal of very little of it.

My love for American Southern Gothic, Western and horror stems from the those genres’ lack of pretension, by and large. These are stories of life and death; morality tales where good and evil occupy the same space. These are timeless tales that could have easily come out of The Bible if the settings and language weren’t so readily identifiable as American.

Allow me to revel in this cliché: Cormac McCarthy is one of the great American authors, with a body of work that includes some of the most important books of the 20th century. A champion of both the Southern Gothic and the Western, his words shape landscapes of stunning beauty and harrowing violence; places where hope is often a direct path to greater tragedy. His characters do not often get what they want and things do not usually end well, but these dark nights of the soul inevitably lead to enlightenment through suffering, a greater idea of purpose, and a more complete picture of what it means to be human.

Like so many boring middle-aged men, I am constantly trying to rip off Mr. McCarthy in my own half-cocked way. I write songs about isolation and alienation, loneliness and regret. My work is a banal prayer for redemption, peppered with moments of hope among ubiquitous violence. There is little to nothing original about what I write, and I am at peace with that. I write about subjects that I identify with, in a manner that makes sense to me. I write for spiritual and psychological release. I write because, although conceptually unoriginal, the thing that I want to create doesn’t quite exist yet.

Now, what the fuck does any of this have to do with Cormac McCarthy?

Cormac McCarthy Is Not Hung Up On Originality

How much dog shit gets shoved into that bottomless hole, just for the sake of throwing the proverbial spaghetti at the wall in the hope that someone might call you an innovator? Artists just love to rot on the cross of originality. It is a self-indulgent, boring exercise that leads many to the pit of resentment because nobody recognizes their genius. If you’ve got a good idea you might as well go for it, but most of us sure as shit ain’t Pynchon. Now, as great as Cormac McCarthy is, his style and subject matter isn’t exactly original. His career, particularly early on, can be read as a continuation of William Faulkner’s work, from subject matter to style. Much in McCarthy’s Tennessee Appalachian books seem to run in parallel to the events of Light In August and Go Down, Moses. As far as the absence of quotation marks goes, look no further than James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Hubert Selby, Jr. or any number of others.

McCarthy is a genre writer above all else. He writes gothic. He writes Westerns. He writes post-apocalyptic dystopian fiction. He writes horror. Everything he does has been done before, he just does it better than most. I try to keep this example in mind every time I start writing weird for the sake of writing weird. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel when your goal is to make something relatable. Now, I’ll never be one iota as good as Cormac McCarthy at anything at all but if he’s content to walk in the shadow of giants maybe I should worry less about being original and more about not falling on my fucking face while trying to structure a sentence.

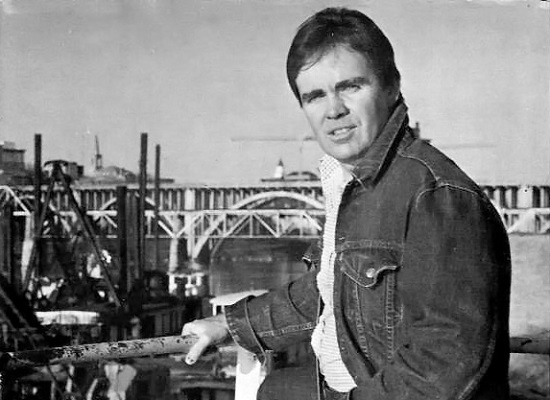

Cormac McCarthy from the inner sleeve of Suttree, 1979. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Religious References

Cormac McCarthy’s body of work is littered with religious allegory. Whether it be Red Branch as a stand-in for Eden in The Orchard Keeper; the character names and events in Outer Dark as probable references to the Corinthians; the abilities, cunning, and physical stature of The Judge in Blood Meridian bearing a resemblance to any number of omniscient antagonists from the Gnostic archons to Satan; the overt Catholic symbolism of All the Pretty Horses; and the merging of Revelation with elements of the Creation myth that are ever present in The Road, you’ll bump into a mountain of symbolism regarding faith, doubt, free will and identity pretty much anywhere you venture within any of McCarthy’s body of work. His sparse prose shows a fluency with biblical style.

Like most of The Bible, he shows a deep empathy with the downtrodden sinners of the world and a persistent suspicion of authority figures and those with socioeconomic power throughout his writing. Although he grew up Roman Catholic, McCarthy hardly considers himself devout. Instead, he recognizes the use of spirituality as a practical application. When asked by Oprah about his relationship with God, McCarthy responded: “It would depend on what day you ask me. I don’t think you have to have a great idea of who or what God is in order to pray… you can be quite doubtful about the whole business.” As an intermittently practicing Catholic, I highly identify with this sentiment. In my stupid little songs, I tend to write about those who call on God out of desperation or exhaustion. This mirrors much of my own personal relationship to religion. I often believe in God, although I could never begin to understand what that means let alone articulate it. Sometimes I don’t believe in God at all, and that’s perfectly fine. The act of prayer hasn’t hurt me yet.

Not Quite Arbitrary Violence

Violence, either direct or implied, is a constant device employed throughout all of Cormac McCarthy’s body of work. The spectre of death is ever present. Personal and spiritual development is achieved through great suffering. Violence is used both to shock the reader and to lull them into a dull complacency. Murder is a fact of life, a necessary evil towards the greater good of self-preservation. Genocide becomes monotonous. The flaming dumpster that I try to pass off as creative writing is also littered with violence, albeit much less effectively. Maybe one day I’ll get the hang of it. Don’t hold your breath and I won’t hold mine.

Isolation As Theme

The characters in Cormac McCarthy’s books by and large traverse a desolate world alone. Rinthy and Culla set off on their own separate quests in Outer Dark. Lester Ballard exists in a world beyond the margins in Child Of God. The Man and The Boy in The Road exist at the end of humanity, literally. Even when they are among companions they retreat into their inner lives and personal motives. The Kid might travel with the notorious Glanton Gang in Blood Meridian, but he is still very much alone throughout the book. In McCarthy’s world, sense of purpose and inner peace are achieved through isolation and great suffering. In my own work, I tend to write about people on the fringe. They are the drunks, the junkies, the mentally ill. Broken down and stripped of dignity, they are cast to the fringes. However, this is not a world beyond hope. I try to write about growth through pain, be it physical or existential. They are largely responsible for their own misery or happiness. Things might not always end well, but the journey is more important than the destination or whatever.

Uniform’s new album Shame is out on September 11 via Sacred Bones