Though the precise date and time in the summer of 1980 have long since faded, the memory remains strong. Having forked out the princely sum of £3.49 in Our Price in Slough, the journey home on the – yes, really – 69 bus was one of near unbearable excitement and anticipation. Removing the album from the record store’s bag, it was impossible not be transfixed by the album’s cover: sleek, black and utterly inscrutable, there was nothing here to hint as to what was to be expected. The band’s instantly recognizable logo was embossed – embossed! – at the top of the cover. Tilting the record this way and that, the album’s stamped title would reveal itself in the light, and running my fingers over it only added to the enigma.

Here was Back In Black, the album that would arguably prove to be rock music’s greatest comeback.

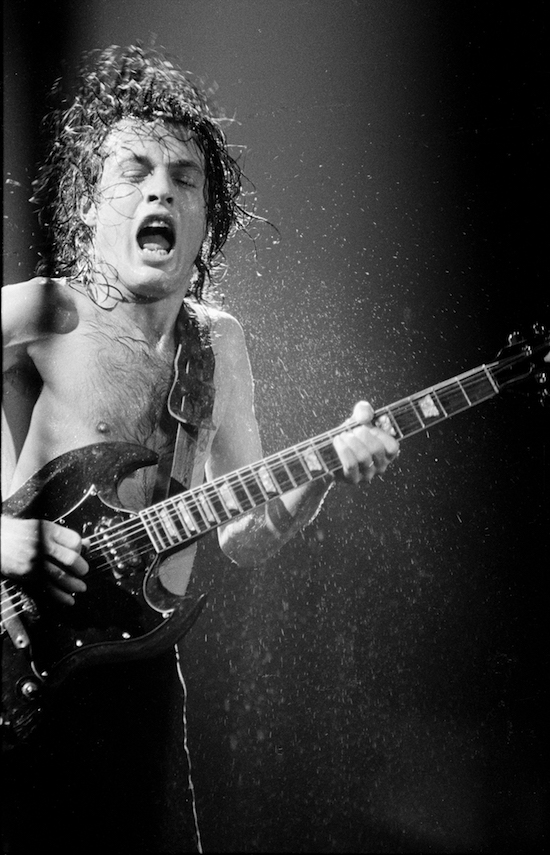

The inner sleeve added to the sense of expectation and mystery as the bus made its way to my stop. Robert Ellis’ celebrated photos show guitarists Angus and Malcolm Young, bassist Cliff Williams and drummer Phil Rudd deep in action, while new singer Brian Johnson is leaned up against a wall, giving no hint as to what was to come. It was as if we were being taunted: “You know what the band can do, but wait ‘til you hear the pipes on this fella…”

And even as the needle found the groove for the first play, it would take another 90 seconds for the new AC/DC to fully reveal themselves. First came those five somber bell tolls – there are, spookily enough, 13 in total – that dimly recalled the opening to opening to Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut. But whereas the Sabs’ bell sounded distant and far, here was something closer, more menacing and infernal. Followed by Angus Young’s ominous chiming riff and Malcolm Young’s punching A chord, Phil Rudd’s steady bass drum ramped up the tension before his fills welcomed Cliff Williams’ throbbing bass. As the music took flight – full, majestic and spacious – the realisation crept in that this was unlike anything the band had tried before.

And then came that voice: “I’m rollin’ thunder, pourin’ rain…” Rasping, lived in and experienced, it wasn’t what was expected, but it was everything that was needed. And the reaction of fans hearing this for the first time was pretty much unanimous – the band and Johnson were not only made for each other, they were surpassing all that went before it.

And so it went with the rest of the album – one knock-out punch after another: the balls-out rock of ‘Shoot To Thrill’, the groove of the title track, the instantly memorable ‘You Shook Me All Night’, the grimly hilarious ‘Have A Drink On Me’ and more. So much more. For a band that seemingly cared little for singles, Back In Black felt like a Greatest Hits compilation: not a note was wasted, no hook failed to catch its prey.

Back In Black is couched in a romanticism that’s perhaps misplaced, not least as this is an album born of tragedy. With AC/DC riding high on the success of Highway To Hell, singer Bon Scott was found dead in a car in south London in February 1980 after a night of heavy drinking and partying. For many, Scott was as much a totem for the band as was Angus Young. While Angus became the band’s undisputed visual trademark, it was Scott’s ribald tales of life on the road, boozing, carousing and the drudgery of daily life that came to define AC/DC in the eyes of their fans. Scott not only embodied the mythology of rock & roll, he was also very much the real deal offstage as he was on, and his premature death at the age of 33 froze that image forever. And yet with his demise came the very real possibility that eight years’ worth of work would come to a grinding halt.

But it’s also an album of born of necessity. It’s been suggested elsewhere that the speed at which Brian Johnson replaced his predecessor was driven by a ruthlessness on the part of the Young brothers, but this is to ignore the fierce work ethic that had been instilled in the family since they arrived Down Under from Scotland in the early 1960s on the ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme, the programme designed to increase the population of Australia by offering British citizens cheap passage to get there. And in any case, who could blame them? To have finally cracked the UK Top 10 and the US Top 20 album charts with the million-selling Highway To Hell and then given up would’ve proved scant reward.

Yet speed was of the essence when it came to the creation of Back In Black. Having been encouraged by Bon Scott’s grieving parents to carry on with the band, the Youngs wasted no time in auditioning a series of singers before announcing on 1 April – a mere six weeks after Scott’s death – that Brian Johnson, formerly of glam also-rans, Geordie, was in. By the end of the month, AC/DC and producer Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange were ensconced at Compass Point Studios on the island of Nassau in the Bahamas. Five weeks later and Back In Black was in the can. So quick was the process that Atlantic, the band’s then-label, ran with a first-draft and erroneous track-listing on the back cover without double-checking the running order with the band.

Back In Black arrived at a crucial time in the development of heavy metal. As with Motörhead, AC/DC had little truck with the genre label, viewing themselves purely as a rock & roll band. Yet be that as it may, the album’s release coincided with the moment that the trajectory of those heavy bands formed in the 1970s crossed with that of the emerging New Wave Of British Heavy Metal. So while AC/DC had begun to break out of their cult status in the wake of Highway To Hell, so too did Brummie stalwarts Judas Priest, who released their Top 5 album, British Steel, in April 1980. Like AC/DC, Judas Priest had streamlined their sound and polished their production, and it’s hardly a stretch to conclude that their support slot on the European leg of the Highway To Hell tour had some influence on their output.

Snapping at their heels were the debut releases by Def Leppard (On Through The Night) and Iron Maiden (Iron Maiden), as well as Saxon’s second album, Wheels Of Steel. Indeed, both Iron Maiden and Saxon had scored hit singles with ‘Running Free’ and ‘Sanctuary’ (numbers 34 and 29) and ‘Wheels Of Steel’ and ‘747 (Strangers In The Night)’ (numbers 20 and 13) respectively. Elsewhere, Motörhead had actually ram-raided the UK Top 10 by peaking at No.8 with the gloriously raucous four-track live EP, The Golden Years.

What this meant in practical terms for AC/DC was they were able to add a whole new generation of young fans to those whose numbers had been swelling throughout the Bon Scott years. In a canny move, the singles ‘Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap’, ‘High Voltage’, ‘It’s A Long Way To The Top (If You Wanna Rock & Roll)’ and the live version of ‘Whole Lotta Rosie’ were swiftly re-issued in the slipstream of ‘Touch Too Much’s chart success. Yet AC/DC’s move into stratospheric levels of success came not with the singer who’d led the charge, but with someone new.

Not that AC/DC were alone in this position. The previous year had seen the release of Rainbow’s fourth album, ‘Down To Earth’. Itching for commercial success, bandleader, guitarist and minstrel-to-be Ritchie Blackmore had yet again re-shuffled his line-up. Caught in the crossfire was singer Ronnie James Dio, who tipped up with Black Sabbath after they’d fired frontman Ozzy Osbourne for excesses so great that they impeded his ability to make any meaningful contribution.

But there remains a crucial difference that separates AC/DC from either Rainbow or Black Sabbath. For sure, all three bands replaced their singers, but AC/DC made the switch through tragedy and without making a fundamental alteration to their core sound. So while Rainbow’s version of ex-Argent guitarist Russ Ballard’s ‘Since You’ve Been Gone’ gave the band their then-biggest hit, it was as far away from ‘Stargazer’ as was the reading of the Ballard song by Clout (they of ‘Substitute’ fame), which they’d covered the year previously.

Elsewhere, Black Sabbath sounded completely rejuvenated on the incredible Heaven And Hell. Released in April 1980, their ninth studio proved to be a remarkable bounceback after a series of lacklustre albums. With Ronnie James Dio taking hold of the lyric writing reins, his flair for vocal melodies was at stark odds with his predecessor’s style of following Tony Iommi’s monolithic riffs. In much the same way that Vol. 4 sounds as if it had skipped an album after Master Of Reality, so Heaven And Hell felt like an album that was separated by several records from the release of the dire Never Say Die.

Unlike AC/DC’s Back In Black that, despite the necessary change in singer, sounded exactly where they were heading for. It’s long passed into folklore that AC/DC have made the same album each and every time they’ve stepped into a studio, but this is to ignore the evidence to contrary, especially where Back In Black is concerned. Over five internationally released albums, AC/DC had transcended their glam rock roots via a series of increasingly yet deceptively sophisticated releases.

Their relationship with producer ‘Mutt’ Lange yielded the international hit album Highway To Hell, and the title track would go on to be a staple of classic rock radio stations in the decades to come. A production genius, Lange’s role in helping AC/DC break through to a wider audience can’t be overstated. Whereas the previous production team of Harry Vanda and George Young focused on the performance – warts & all – Lange was a perfectionist who understood the dynamics of sound. Hence guitars were tuned to concert pitch, the drums were given space across the mix, the bass a deeper and smoother throb, and the backing vocals were straight from the terraces. And as he’d helped Bon Scott with his studio performance, so he encouraged from Brian Johnson the performances that would slot neatly into the sound generated by his bandmates. Back In Black wasn’t so much revolution, then, as evolution.

And yet in other areas, Back In Black took some steps back. Despite Lange coaxing some of the album’s best lyrics from Johnson – the words to ‘Hells Bells’ were written as a tropical storm hit Nassau – other areas were left wanting. At a remove of 40 years, ‘Given The Dog A Bone’ (later re-named to ‘Givin The Dog A Bone’) and ‘What Do You Do For Money’ sound utterly mean-spirited. There was always a twinkle of mischief in Bon Scott’s eye, and he frequently came out second best in his encounters (see ‘Whole Lotta Rosie’ and ‘Shot Down In Flames), but here, Johnson – and most likely the lyric committee of the Youngs, Lange and engineer Tony Platt – sounds as if he’d been half-listening to Scott in a crowded pub and misunderstanding the conversation.

But when the lyrics did strike home, they did so with deadly and frequently hilarious effects. The origins of ‘You Shook Me All Night Long’ have been the focus of intense debate in other pages, but whatever their source, “She told me to come but I was already there” is a work of bawdy genius. Elsewhere, it’s impossible not to laugh at the utter tastelessness of ‘Have A Drink On Me’. With a singer dead from boozing, only AC/DC could have come up with “Whiskey, gin and brandy/ With a glass I’m pretty handy/ I’m tryin’ to walk a straight line/ On sour mash and cheap wine” in tribute.

And of course, tributes don’t get much bigger than ‘Back In Black’. Swaggering, confident and a total slave to the groove, this was the moment the realisation crept in that Side 2 of the album was going to be every bit as good as the flip. But it also sounds, in retrospect, as much a statement of intent from AC/DC as it was a salute to their fallen singer. Those “nine lives” could so easily be predicting the line-up changes that would occur over the next 15 years before this line-up reconvened with Ballbreaker.

Indeed, one of Back In Black’s legacies is that allowed the constant merry-go-round of line-up changes that’s one of heavy rock and metal’s chief characteristics. Iron Maiden would go on replace singers (not once but twice, as well as guitarists and drummers), as would Judas Priest, Van Halen and Black Sabbath among others. But we can also thank ‘Back In Black’ for inspiring the goth bands that swapped the spiky chicken for headbanging. The Cult’s Electric is a case in point, as well as being a dry run for producer Rick Rubin’s later work with AC/DC.

For all of its shortcomings, Back In Black is an album that endures. With sales at the 50m mark, it remains the biggest-selling rock album of all-time, and is second only to Michael Jackson’s thriller. So clearly, it’s doing something right. And what it does right is to capture the very essence of adolescence. It is crass, stupid, irresponsible and carefree – and recommendations don’t come higher than that. And it was those crass, stupid, irresponsible and carefree adolescents that propelled Back In Black to the top of the charts in 1980, and it’s those crass, stupid, irresponsible and carefree adolescents of all ages that continue to help sell it by the truck load now.

Bon Scott isn’t the only one frozen in time. With Back In Black, AC/DC ensured they were stuck at being 15-years-old for the rest of their career. And that’s no bad thing because that was and is a time of cheek, laughs and innocence. It’s an album made by (overgrown) kids for (overgrown) kids. Its song titles totally eschew punctuation, like someone who’s bunked off every single English lesson at school ever. It’s rock & roll at its most elemental and effective and it totally bypasses the brain and aims for the feet. And every time it gets pulled out, I’m back on the 69 bus and experiencing that same sense of excitement and anticipation of what’s to come.

And that’s a journey worth taking time and time again.