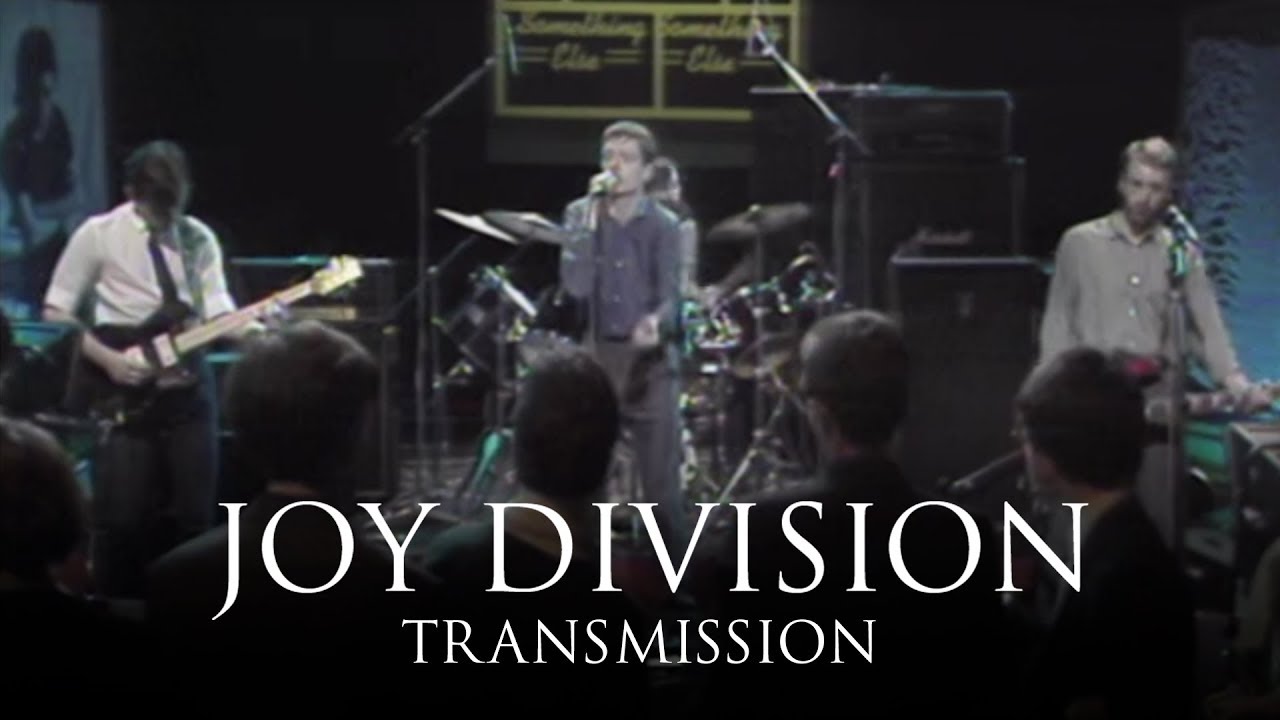

In 1979, for even the most avid NME reader living outside Britain’s big cities, it wasn’t easy to get to see new bands. Sure, you could hear them on John Peel, but that didn’t tell you anything about their stage demeanours. It follows that many of those who watched Joy Division perform ‘Transmission’ and ‘She’s Lost Control’ on BBC Two’s Something Else programme on 15 September 1979 had little or no idea of what to expect.

What viewers saw was extraordinary. Here were the young men: Peter Hook scowling, bass hung low, guitarist Bernard Sumner lost in concentration and Steven Morris busily keeping time. But what really commanded the attention was the fierce intensity of frontman Ian Curtis, a man possessed, spasming and running on the spot to keep up with the music that had taken him over.

In their sole appearance on national TV, Joy Division left an indelible impression. And for those already paying attention, there was the sense this was only the beginning, that this was a band already moving beyond Unknown Pleasures, released in June 1979 and a debut where, for all the eerie spaciness in the music, Joy Division’s roots in punk were clearly discernible.

Tragically, it was a journey that, because of the suicide of Ian Curtis on 18 May 1980, had already ended by the time the band’s second album Closer was released in July that year. Four decades on, it remains an extraordinary record, an album where Joy Division and producer Martin Hannett distilled the band’s sound, its icy clarity a counterpoint to lyrics that, to quote journalist Paul Morley, were written by a man who "was on the edge of the abyss" and "was actually experiencing trauma in real time and pressing it so precisely into his lyrics".

No band ever travelled further than Joy Division in these months. But how did this happen? How do you explain the mystery of Closer, or of ‘Atmosphere’ and ‘Dead Souls’? At the very least, any answer needs to take in Factory’s maverick commitment to letting musicians control their own trajectories, the singular genius of Hannett, Manchester and, most of all, the alchemy that occurs with all the greatest bands.

On a more practical level, the autumn of 1979 was when Joy Division said goodbye to the notion of distracting day jobs. "Literally we’d been professional for just over six months before we actually finished," says Peter Hook, "if you can call professional being on three quid a day."

In part, this was a decision rooted in practicalities. In October 1979, Joy Division began a national tour supporting Buzzcocks, a band that had offered help and advice to Joy Division. "The Buzzcocks were playing to big audiences, so instead of these horrible toilets that you normally got changed in, you were actually in a modicum of comfort," Hook said when he first spoke to me last year for a feature published in Long Live Vinyl magazine. But not that much comfort. Buzzcocks, he added, had a minder charged to stop Joy Division’s "starving musicians" stealing Buzzcocks’ rider.

Buzzcocks, in the wake of A Different Kind Of Tension, an album that’s aged better than it was received, were beginning to struggle and eventually called it a day in 1981. "I actually felt sorry for the Buzzcocks because they’d gone off on this experimental tangent and had alienated their audience," said Hook. "We came on and gave their audience exactly what they wanted, and we were blowing them off every night. Amazing." Pete Shelley was "aghast".

In October 1979, Factory released ‘Transmission’. It’s a thrilling record, dark and propulsive, but it already represented Joy Division’s past. At some point in October and November, the exact dates seem lost in time, Joy Division went into Cargo Studios in Rochdale and recorded three songs: ‘Atmosphere’, ‘Dead Souls’ and ‘Ice Age’.

Astonishingly, Joy Division gave away the first two songs for the Licht und Blindheit (‘Light and Blindness’) package, a limited-edition single released by French label Sordide Sentimental in 1980. "We were lunatics," concedes Hook. Was this maybe because Joy Division felt they could write more songs as good? "We knew, we didn’t feel, we knew, next time we go in, we’ll write another one. Absolutely unbelievable."

It’s a record that early on begins to crystallise the band Joy Division would all too briefly become. ‘Atmosphere’ is stately and eerie, yet built around a sweet hook that’s really not too far removed from Bread’s ‘Guitar Man’. ‘Dead Souls’ was a rangefinder of a rock song, with which Joy Division opened live sets so that Curtis could use its long instrumental introduction to size up the audience.

There’s a subtle contrast here with the two tracks Joy Division performed on Something Else. ‘She’s Lost Control’ and ‘Transmission’ essentially build to crescendoes. ‘Atmosphere’ and ‘Dead Souls’ are supple, they ebb and flow – and ‘Dead Souls’ employs the musical trick Bob Dylan happened on via Al Kooper’s impromptu organ part to ‘Like A Rolling Stone’, the sense the song is about to break down before it surges again.

The dynamics of Joy Division’s performances and songs were changing, something you could see and hear happening, according to Paul Morley. "I remember the shows being somehow so much more monumental and majestic than the venues they were playing, like they were bursting to get out of the small clubs, the support slots, their own limited ability. They had grown so quickly that their power and dynamic, the performative art of Ian, was far greater than their immediate status, and during one show you could hear them advance, mutate, move into more urgency."

On 16 October, taking a break from the Buzzcocks tour, the band, along with Cabaret Voltaire, performed Plan K in Brussels, their first European show (they would return to Europe again in 1980), and where, reputedly, William Burroughs told a crestfallen Curtis to fuck off when the singer tried to blag a book. Annik Honoré, whose relationship with Curtis plays into so many of Joy Division’s later songs of regret and self-recrimination, helped organise the show.

Joy Division were in the ascendency, to the extent that Hook talks of the way the band could give away their best songs for limited-edition singles as being "wonderful", "intoxicating" and, rolling out his Tony Wilson impersonation, "sublime, darling". But there was also a shadow, the epilepsy with which Curtis had been diagnosed in January 1979 after beginning to suffer from seizures in 1978.

While the band and manager Rob Gretton insisted that no strobes or flashing lights were used when Joy Division performed, it’s at best doubtful whether Curtis should have been performing at all, for all that his bandmates grew used to the condition.

"Looking after Ian became second nature really, it was just something we did all the time," says Hook. "I remember when we did the gig in Bournemouth [in November 1979]. God, I held his tongue for nearly an hour until he came round, and we were all sat there, joking round him." When the worst of the seizure had passed, the band took Curtis to hospital.

In interview, Hook is garrulous, funny, given to undercutting himself when he gets too serious, but the underlying regret over Curtis is palpable. Yet it’s coupled with an acknowledgement that Curtis was driven. "He had his doctors, he had his parents, there were older people around but you couldn’t stop him," says Hook. "He knew what he wanted to do.”

Ask Hook directly what Curtis was like and he replies, "He was a lovely, lovely man and he was loyal. He might have been a bit two-faced maybe, but aren’t we all? He loved his group. He was a great leader. He was passionate. He burned every time you played, the guy burned, it was like this human torch. For the first year and a half of Joy Division, I couldn’t understand a word he was saying, but every time I looked at him, I thought, ‘Jesus, I don’t care what he’s saying, he just fucking means it.’"

Through the rest of 1979 and into 1980, Joy Division honed their sound. The results of this work were recorded for posterity over two key sessions. On 13 March, at Strawberry Studios in Stockport, the band nailed the single version of ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, previously recorded in January, and a 12" version of ‘She’s Lost Control’. Tony Wilson, notes Hook in his autobiography Unknown Pleasures, was encouraging Curtis to listen to Frank Sinatra at this time.

On 18 March, Joy Division began work on Closer. While Unknown Pleasures had been recorded at night in Stockport, Closer was recorded at Britannia Row in London, built by Pink Floyd, and where they recorded Animals and parts of The Wall. Here was the kind of studio and situation in which Martin Hannett could stretch Joy Division’s sound still further.

Much has been made over the years about the ways in which Hannett did or didn’t shape Joy Division’s sound, but it’s hard to imagine the band having the impact they did without him. Similar to Curtis, he’s a figure endlessly mythologised, in Hannett’s case for the ways in which he used the studio to manipulate sound, while also being a figure demonised for his spiky persona, prodigious drug use and a carelessness about his own health that led to him becoming obese in later years and dying relatively young.

Dave Formula, Magazine’s keyboard player, was a friend of Hannett’s, who shared a flat with him in the 1970s. The relationship was professional too and Hannett rated Magazine’s The Correct Use Of Soap, also now 40 years old, as his best production work. "He was a man of obsessions," says Formula. "He became really obsessed with AMS [the studio technology company he advised] delays and reverb units. He loved Volvo cars. He loved cheese on toast." The two men talked about production for hours. Another Hannett obsession, adds Formula, was the snare sound on Randy Newman’s ‘Baltimore’ (1977), which has something of the snap associated with Stephen Morris’s drum sound.

The other side of Hannett was that he could be difficult, obtuse in his instructions to musicians, curmudgeonly. “He hated any kind of incompetence," says Formula, a remark it’s worth emphasising doesn’t refer to Joy Division, "and if you’re a musician and you couldn’t actually play properly or, you didn’t have the attitude to deliver what you were supposed to be delivering, I think he lost his temper with that person very quickly."

Relations were often strained between Hannett and Joy Division, and would break down completely when New Order recorded Movement, but Hook’s memories of being in London for two weeks, a luxury at a time when the band were busy and money was tight, are largely positive. "It was like, ‘Wow, this is big time, Charlie Potatoes,’" he says. "We were all over the moon and yet everything was always tempered by Ian’s illness."

According to Hook, Hannett regarded the band as "three idiots and a genius". On Closer, the producer liked to work alone with Curtis. "We would be working during the day, [but] Martin would try to get rid of us at night so it was just him and Ian," says Hook.

This close attention may help explain the desolate clarity of the vocals on songs such as ‘Isolation’, ‘A Means To An End’ and ‘Decades’, but to return to the idea of Joy Division themselves forging ahead, these were sessions where Hook started using a six-string bass, and where the longstanding interest of Sumner and Morris in electronica came to the fore. These were musicians who embraced experimentation.

In the case of Hook, this was also a musician who initially hated Closer, just as he had hated Unknown Pleasures. "I remember sitting in [Hannett’s] car, listening to ‘Heart And Soul’ and ‘The Eternal’ and thinking, ‘Oh my Christ, he’s done it again,’ which pissed me off."

The point here is that the band often saw Joy Division very differently to the producer. Hannett’s production for Joy Division was all about creating space – a kind of musical inner space, to use a term much employed by the British new wave science fiction writers, JG Ballard and Michael Moorcock, who so influenced Curtis. Hook just wanted Joy Division to sound more like The Clash, "which just goes to show you can never trust a fucking musician even to be a judge of his own music".

If Closer sounds like it’s going ever more deeply into inner space, that’s because it is. One way to think of Unknown Pleasures is to see it as an album strongly influenced by the ruined industrial cityscapes of Manchester. It’s an album of hauntology, in that it seems to yearn for Manchester to be – as its most tireless advocate, Tony Wilson, saw it and talks about it in the documentary Joy Division (2007) – a city where the future is being invented, as it had been during the industrial revolution.

A year later and the band’s musical palette is far wider. Simultaneously, the lyrics of Curtis have become tightly focused, unflinching, terrifying. The sense of Joy Division being a Manchester band is less strong, but the sense of Curtis singing about universal themes – suffering, struggle, loss – is front and centre.

In this, the lyrics reflected his own situation. His health, both physical and mental, was poor. He was torn between his wife, Deborah, the mother of his baby daughter, who was planning to divorce him, and his companion in London during the recording of Closer, Honoré. Twice in the same night in early April, Curtis collapsed on stage. On Easter Sunday, at home in Macclesfield, Curtis took an overdose of a barbiturate used to control seizures, phenobarbitone.

One of the most infamous gigs in Joy Division’s history followed two days later. On 8 April, the band were booked to play Derby Hall in Bury. With Curtis fragile, the band asked Alan Hempsall, frontman with Crispy Ambulance, to step in. But when Hempsall turned up, Curtis was there. It was agreed that Hempsall would sing ‘Digital’ and ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, then Curtis would do the slower ‘The Eternal’ and ‘Decades’, prior to a run through ‘Sister Ray’ without Curtis. It was an idea influenced by supporting The Stranglers at a show where they used multiple vocalists because Hugh Cornwell had been imprisoned for possession of heroin.

"There were a few words on ‘Digital’ that I couldn’t make out and Ian filled us in on anything I was missing," remembers Hempsall, "and then finished off by saying, ‘If you get lost just make it up, I always do.’ He wasn’t precious at all."

The trouble was, nobody had warned an audience expecting to see a conventional Joy Division gig. A bottle hit a chandelier above the stage. All hell broke loose. While Hook went out to take on all-comers, with Tony Wilson trying to hold him back, remembers Hempsall, he and Sumner retreated. "Bernard’s got his feet up on the table going, ‘I hate violence, it’s all so temporary,’" says Hempsall. "He was just calm and really matter of fact about it all, which I thought was really funny."

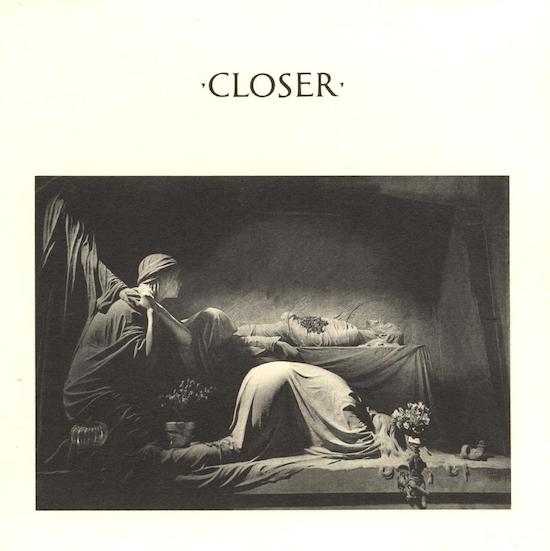

But Joy Division’s situation was anything but funny. Curtis had lost his way. On 18 May, shortly before the band were due to leave for their first US tour, he hanged himself. Closer, its Peter Saville-designed cover featuring a photograph of a tomb in Genoa and chosen prior to the death of Curtis, was released on 18 July. It reached number six. ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, released in June, peaked at number 13. Joy Division had fulfilled their commercial promise, as if that mattered.

What to do next? According to Hook, this had much to do with the man who had always believed in the band, Rob Gretton. "He actually must have looked at us and thought, ‘You know, these twats can do it again,’" says Hook. "And we didn’t think we could so, thank God, he was there to push us. The fact that we carried on is a miracle, but I do think the only reason we did carry on was because we cut it dead, absolutely cut Joy Division off and just ignored it.’"

And so, while Hook now thinks the trio should have taken time off to deal with their grief, New Order were born, a band who in his estimation were "pretty good" but "always like a table with a wonky leg once Ian left us".

With the benefit of hindsight, this decision to move on so definitively left Closer majestically stranded. Sometimes, when Hook talks about Closer, it’s as if it was made by someone else entirely, a product in part he says of never promoting the LP live. When he came to play Closer with his post-New Order band The Light, though, he had to grapple with an album he regards, entirely reasonably, as "perfect". It was a liberating experience. "To play the album in its entirety was so emotional and so fantastic that, at times, it literally took my breath away," he says.

But if Closer seemed an orphan in the immediate wake of its release, its influence on the wider culture has been profound. This is again a story of Manchester, hauntology and regeneration, the same story that Tony Wilson talks about in the Joy Division documentary.

When Manchester’s Science + Industry Museum reopens in the summer, one of its exhibitions will be Use Hearing Protection: The Early Years Of Factory Records, which focuses on the first 50 Factory releases. FACT 25, Closer, is one of six artefacts singled out for deeper attention, according to curator Jan Hicks, because the album represents such a significant step in Factory becoming an international success story, and this in turn was genuinely significant in Manchester’s reinvention, and in the idea of using culture to regenerate cities that Wilson and Factory pioneered.

"You’ve got these European influences coming in, the experiences the band had touring around Europe," she says. "You’ve got Peter Saville’s interest in the history of European design coming through in the record sleeves and in the wider design [aesthetic] of Factory. And so it’s a story of how Factory at that point started to be the new representation of Manchester. They developed this sound and this look and feel, and they were now starting to take it out to the wider world."

In this context, there’s an irony here in that Closer, for all it seems that Curtis is haunted by demons throughout, is the album where Joy Division collectively escape the desolation of Manchester at the beginning of the Thatcher era and in so doing help the city escape too.

From the perspective of someone at work on a biography of Tony Wilson, Paul Morley says, "[Manchester’s story] is about making something out of nothing, about rising to some vague challenge you set yourself, it is about dreaming a future, about surviving disaster and finding a way to compensate for disappointing and depressing surroundings by inventing something for yourself. It’s a great mystery, and it will never be entirely solved."

He could as easily be talking about Joy Division. But the last word here surely belongs to Peter Hook. "It’s a wonderful thing as a man and as a musician to think, ‘You know, I’ll be dead and gone and yet, years and years later, people will still be listening to the bass on those records going, ‘Fuck, this is great.’ I’m very happy about that. To leave a mark on the world is something we all dream of, isn’t it?"

Closer is reissued on vinyl on 17 July alongside 12" singles of ’Transmission’, ‘Atmosphere’ and ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’