The end of the 1960s was, all things considered, not a good time for Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys. The lukewarm chart success of Pet Sounds in 1966 was a major blow to Wilson’s confidence. By the end of 1967, Smile, their fabled would-be masterpiece, was officially shelved, while Sgt. Pepper’s was busy becoming the best-selling rock album in history. His mental health was deteriorating rapidly; a confusing narcotic haze had descended, and it was around this time that his paranoid obsession with Phil Spector became most febrile. (He called Spector a “mind gangster”, paranoid that he was going to extreme lengths just to disturb him.) The Boys failed to show up at the Monterey Pop Festival, fearful that their matching shirts and sweet harmonies wouldn’t go down well with an audience of stoned hippies there to see Hendrix.

To be fair, it’s not hard to see what they were afraid of. This was a group who grew up on Four Freshmen records, whose biggest hits were about surfin’, cars and high school girls, and whose reputation was decidedly un-groovy. They were called The Beach Boys for Christ’s sake. Even the critical admiration garnered by Pet Sounds seemed a lifetime away: in a brutally scathing article, Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner called them “just one prominent example of a group that has gotten hung up in trying to catch the Beatles”. They went from topping an NME popularity poll in 1966 to a hopelessly uncool relic in 1967. The world had moved on.

The rest of the sixties passed by with The Beach Boys spinning their wheels. Brian Wilson was pretty much unreachable to everyone not called Mary Jane, so the band released a couple of placeholder records in the absence of Smile: Smiley Smile, Wild Honey, and Friends which were recorded in his house, simply to encourage his involvement as by this point he was hardly leaving his bed. And then there was 20/20 which consisted mostly of leftovers from a mishmash of turbulent sessions.

Scattered across those albums are glimpses of what The Beach Boys might have been making if they hadn’t been suffering from mental illness, mired in drug abuse, in the midst of violent internal politics, and surrounded by domineering record label suits. Such glimpses include the psychedelic oscillations of Wild Honey’s title track; the nervy, spaced-out Hawaiian pop of Friends’ ‘Diamond Head’; or the choral beauty of 20/20’s ‘Our Prayer’. It’s like panning for gold – there’s a shiny nugget here and there, but a lot of the time you’re just elbow-deep in shit.

And throughout this time, the Boys were showing their remarkable talent for choosing terrible friends. In 1968, frontman Mike Love had become enamoured with Transcendental Meditation and decided the best thing for the band would be to tour with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in tow. They’d play a set, followed by obtuse lectures from the Maharishi advertising the spiritual benefits of TM (available at a great price!)

The tour was organised just after the Beatles publicly denounced the Maharishi. The resulting tour was probably the most disastrous in pop history, with 19 of 24 dates cancelled at a cost of $250,000 (nearly $2m in today’s money). The Beach Boys were nearly ruined; worse, they had become a laughingstock.

Somehow, things got worse before the end of the decade. In 1969 Dennis Wilson opened his house to a new group of friends whose interests included LSD, group sex rituals, armed robbery, and mass murder – thus began The Beach Boys’ entanglement with Charles Manson. Brian and Carl produced a set of Manson songs; 20/20 featured ‘Never Learn Not To Love’, based on the Manson composition ‘Cease To Exist’. And it was through Dennis that Manson met record producer Terry Melcher, who, by refusing to record Manson’s songs, provided the trigger for the tragic Tate murders (Tate was living in Melcher’s old house, which is why she inadvertently became a target). The Beach Boys were now linked to the most famous murderous cult in modern history.

There was a lawsuit with Capitol Records; bankruptcy for the band was looming; they struggled to find a new label; the Wilsons’ father sold their publishing rights for a relative pittance, crushing the sons’ morale; Brian discovered cocaine. Thus began the 1970s for what had once been America’s biggest band.

But The Beach Boys weren’t that easily defeated. They managed to scrape together a deal with Warner Brothers’ Reprise label, and somehow, in amongst all the turmoil, they managed to actually record an album. What’s more, it was a damn good one – Sunflower, eventually released in August 1970, was a substantial growth from the Smile knockoffs and substitutes of the past few years.

For one, it sounds like a proper record with proper songs, and not just a jumble of fragments thrown together in Brian’s bedroom. It was also the first Beach Boys album where all band members started contributing songs in earnest – particularly Dennis. He was the only Beach Boy to have ever really exuded any sex appeal (no offence to the others), and he was the only one who ever successfully embraced soul and funk music. His opener ‘Slip On Through’ thumped harder than any of their songs to date, and ‘Got To Know The Woman’, though riddled with pointless lyrics (“If you feel the feel I feel, you dig the feel of me” – attempt to unpick at your peril), had a throaty Dennis vocal that was positively pornographic for The Beach Boys.

Bruce Johnston, who started as a touring replacement for Brian, also got a couple of tunes in there: ‘Dierdre’ and ‘Tears In The Morning’ are both undeniably cloying, but they’re so unfalteringly sincere as to get away with it. Al Jardine’s ‘At My Window’, an offbeat little oddity about birds, is more honest fun than anything those Scousers ever did. And Brian’s efforts – often with lyrics by Mike Love – are some of his strongest: ‘All I Wanna Do’ drifts by mournfully, backed by labyrinthine vocal harmonies that almost suggest shoegaze, and ‘Cool, Cool, Water’, originally conceived for Smile, showcases some of his most breezy and by turns haunting music.

And, even without appreciating the tumultuous recording environment, the sophistication and inventiveness of the production can be staggering. ‘Dierdre’ blends a brass section, casually strummed guitars, those trademark vocal harmonies, and a prominent flute. ‘Add Some Music To Your Day’ has each member take the lead vocal at some point, shifting almost imperceptibly between moods, slipping in strings and a harpsichord with a deftness that makes it hard to believe there’s so much going on in such a simple-sounding track. And orchestral arrangements by Michel Colombier (who would become most notable for his film scores) give a real pocket-symphony feel to Johnston’s compositions and ‘Our Sweet Love’, a straightforward but strong ballad led by the angelic tones of little brother Carl.

Sunflower ends up as one of their very finest records. Not as revelatory as Pet Sounds, sure, but there was a genuine depth to what they were doing. Gone were the days of waiting for Brian to hand over little bits of his genius; The Beach Boys were a rock band, and they started acting like one. They all mucked in, wrote some good tunes, recorded them brilliantly, and packaged them up on two coherent sides of wax. What more can you ask of a rock band?

Apparently, quite a lot more. The first tracklist submitted to Warner was rejected flat out. After some reworking and additional studio time, it was begrudgingly accepted. The UK warmly received Sunflower, critically and commercially, but in the US – where it mattered, for “America’s Band” – it became their worst seller to date. Jim Miller in Rolling Stone appreciated its merits, but then remarked: “It makes one wonder though whether anyone still listens to their music, or could give a shit about it.” Miller continued: “This album will probably have the fate of being taken as a decadent piece of fluff at a time when we could use more ‘Liberation Music Orchestras’.”

The comparison is a little unfair – a summer pop record versus an avant garde jazz protest album – but the judgement is telling. It was 1970: the height of the counterculture. Violent protests were consuming the streets; New Hollywood was punching its way through cinema screens; Vietnam was on America’s mind. The Beach Boys – barely out of their matching stripy shirts – were still not on the same page as the rest of their country.

Someone realised this at the time: a Los Angeles radio presenter named Jack Rieley, after interviewing Brian on air, wrote to the band. In a six-page memo, he detailed what he thought the Boys’ problems were, and how he thought they could fix them. The Beach Boys needed to embrace the turbulent times around them and comment on society’s ills. They needed to be heavier, funkier, trippier. They needed to engage with the counterculture.

Nick Grillo, the band’s long-suffering manager at the time, recalled: “Nothing was happening in their [the Boys] careers… they were just sitting back and waiting for a new voice, and Jack Rieley was that voice.” He was hired immediately, and effectively took over management of the band.

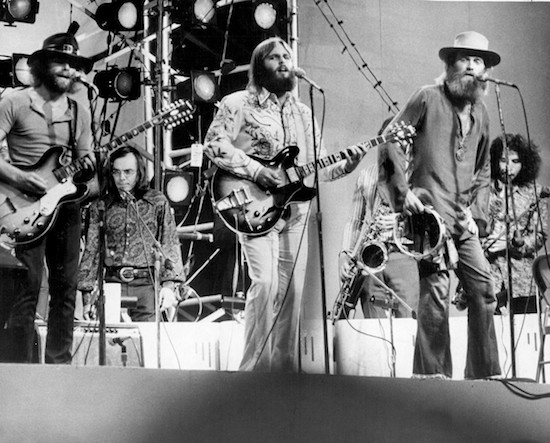

What followed was a string of fortuitous live performances which boosted The Beach Boys’ reputation, at least amongst the West Coast rock intelligentsia (the subculture the Boys were always desperate to impress). They played the Big Sur Folk Festival and knocked their audience dead. They played four sold-out nights at the Whisky A Go Go – that temple of LA hard rock to which the Doors, Zappa, Led Zep, and the Byrds all owed their success.

As 1971 rolled on, they took their act nationwide. For probably the first time in their lives, they started really working hard: playing non-stop shows at shit venues to tiny audiences for meagre fees. But it was working. They were clawing their way back from the grave.

Then, in April 1971, at the Fillmore, New York, something magical happened. The Grateful Dead were playing to their usual audience of stoned and/or acid-tripping hippies. After three hours of psychedelic jazz-rock, Jerry Garcia suddenly announced: “Now we’d like you to welcome some fellow Californians… The Beach Boys.”

And the crowd went fucking nuts.

The Grateful Dead/Beach Boys gig is a veritable slice of rock mythology. Bootlegs became things to be spoken of in hushed tones, whispered through clouds of seventies weed smoke. The unthinkable had happened: The Beach Boys had become cool. The counterculture which had baffled and spurned them just a year ago began to see them for what they were: vital musical innovators; the forerunners to all their favourite bands; authors of their childhood soundtracks; and killer live performers. In May, they played at an anti-war demonstration in Washington, D.C., solidifying their reputation as being right on.

In amongst their relentless touring, they also managed to make the (second) finest album of their career. Surf’s Up, released in July 1971, showed a new side to The Beach Boys – that much is clear just from the album art. Gone are the happy-go-lucky, cherub-faced boys of albums past; here is an image of defeat and exhaustion, splashed in morose hues of blue and green; an image of mythological American death. The title suggests an ironical play on the music that made them famous – surf’s up, over, done. With Jack Rieley’s nudging, The Beach Boys began to join in the harder-edged realism which had overtaken the flower power, free love idealism of the 60s.

But Surf’s Up isn’t hard – it’s a desperately sad record, despite all the ba-ba-mm-mm harmonising. The album opens with Mike Love and Al Jardine’s ‘Don’t Go Near The Water’ – a lyrical declaration which, coming from The Beach Boys, is heartbreaking. The band who once claimed that everybody’d be surfin’ like Californ-i-a were warning that “our water’s going bad”. The song is one of two ecologically conscious numbers on the album, the other being ‘The Day In The Life Of A Tree’, a bizarre flight of fancy written by Brian at his most eccentric and sung by Rieley himself (apparently the band thought the lyrics were “too depressing” to sing themselves).

There was socioeconomic commentary, too: ‘Looking At Tomorrow (A Welfare Song)’ (another Jardine effort) is exactly what it claims to be, with the narrator lamenting that “all the good jobs they were had/ I had to take to sweeping up some floors”. Not exactly groundbreaking sentiment, but the sparse, reverb-laden production makes it positively chilling.

The most overt political references were found on the Mike Love-penned ‘Student Demonstration Time’. Though piled high with wacky sound effects, it’s a pretty basic hard rock reworking of R&B standard ‘Riot In Cell Block Number 9’, with Love’s lyrics inspired by the 1970 Kent State Shootings. That tragic incident also inspired Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s protest anthem ‘Ohio’, which is a much better song. But give Mike an A for effort – even if he comes to the limp conclusion: “I know we’re all fed up with useless wars and racial strife/ But next time there’s a riot, well, you best stay out of sight”. That’s alright for some.

The real star of Surf’s Up, though, is Carl. He wrote and played nearly every instrument on the gorgeous ‘Long Promised Road’, which alternates between Moog-foregrounding ballad and rousing rocker. “Sew up the wounds of evolution and the now starts to get in my way,” he sings, providing some of the band’s most thoughtful lyrics. And: “So hard to laugh a child-like giggle when the tears start to torture my mind” could be a synecdoche for the whole album.

He also penned (with Rieley) ‘Feel Flows’, a heartfelt and somewhat psychedelic piece that sounds like he’s watching his big brother Brian drift away from the world. Whichever way you slice it, it’s a real gem, featuring Carl’s sweet tones backwards-echoing atop layers of vocals, organ, piano, and then a guitar-flute-sax-moog solo section.

Add in Bruce Johnston’s ‘Disney Girls (1957)’, a nostalgic weepy and the best song he ever wrote, and ‘Take A Load Off Your Feet’, a silly but irresistible tune about, uh, looking after your feet, and you’ve already got a great record. Not just that: at long last, The Beach Boys recognised the times they were living in. Their songs were once about having fun, loving girls, and living fast and loose; now, they were about the memories of fun, the struggle to love, and the injustices of the world (admittedly, ‘Take A Load Off Your Feet’ is about none of the above). In short, The Beach Boys had arrived in the seventies.

But Surf’s Up saves the best till last. Penultimate track ‘’Til I Die’, could be, in hindsight, Brian’s last real gasp of brilliant writing before being totally consumed by drugs and ill-health. It cycles through increasingly plaintive chords with lyrical resignations like “I’m a cork on the ocean/ Floating over the raging sea” and “I’m a leaf on a windy day/ Pretty soon I’ll be blown away”, before sliding into circular harmonies of “These things I’ll be until I die”. Not exactly cheery, but as a reflection of Brian’s mental state – again, defeat, loss, sadness – it’s perfect.

And following ‘’Til I Die’ is the title track. Another piece originally intended for Smile, ‘Surf’s Up’ is a flat-out masterwork. It has the song-within-song structure of many Smile-era Brian compositions, and a twinkly-eyed loneliness that lets the song slip into the rest of the album seamlessly. The Van Dyke Park lyrics, in his typically esoteric fashion, sound like The Waste Land by way of Wagner; it’s the haunting echoes of a dying civilisation. “Columnated ruins domino,” sings Carl, an initially impenetrable line Brian explained in 1967 as: “empires, ideas, lives, institutions – everything has to fall, tumbling like dominoes.” In 1971, after his once-unassailable band had hit rock bottom, I’m sure he appreciated that sentiment more than ever. Accompanying the words is his richest composition, bringing in a muted French horn, some glockenspiel, more pads of modular synthesizer, elastic tempos, inspired key changes, and some of his most heavenly vocal work. You could write a dissertation on how good this song is. And it barely cracks four minutes. ‘Surf’s Up’ is the spectacular pinnacle of all The Beach Boys’ genius, and it tops off the record beautifully.

Surf’s Up emerges as the most impressive record of their career – Pet Sounds might be better, but Surf’s Up is the first, and maybe only, Beach Boys effort where they actually sound mature. They had transmuted their innocence into weariness without sacrificing their sincerity, and retained their unimpeachable technical excellence. They were rewarded with their best-selling album since 1967.

So, what next? Fire a band member and start playing roots rock, of course.

In 1972, Bruce Johnston was dismissed (or resigned, depending on who you ask) following a disagreement with Jack Rieley and replaced by South Africans Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar. Rieley was also responsible for the band’s new direction: there was a counterculture out there that needed hard, rootsy, funky, soulful music, so The Beach Boys should be harder, rootsier, funkier, more soulful. Never mind that Surf’s Up’s inimitable sound had satisfied the counterculture, and that the roots crowd already had the Band, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Traffic, the Grateful Dead…

The result, Carl And The Passions – “So Tough”, released in May 1972, is a record that lacks the heart of The Beach Boys. It’s got some decent tunes, sure. ‘Marcella’ is typically excellent in production and a joyful piece of songwriting. But CSNY impression ‘Hold On Dear Brother’ and the Traffic-aping ‘Here She Comes’ both go nowhere interesting. Worse: hearing them imitate a black Louisianan church band on ‘He Come Down’ is a kind of soul-destroying. This kind of musical blackface was rife at the time – the Stones, Joplin, Creedence, Led Zep – but at least the aforementioned had the sense to perform it with some conviction. The Beach Boys are white to the core though. Their affected southern drawls are, well, embarrassing as much as offensive.

Brian also had very little to do with ”So Tough”, and it shows. Lacking are the quintessentially Brian tracks that make Beach Boys records so special. Gone are the sudden tonal shifts, the where-did-that-come-from key changes, the what-the-hell-is-that-instrument moments, the wacky sound effects. The public also saw through their attempts to be something they weren’t, and “So Tough” made a rather weak commercial showing.

Never mind, there’s always a new fad to try. How about moving to Holland, boys? So said Jack Rieley, and Jack’s word was gold. So the band upped sticks and rented no less than eleven houses around Amsterdam, then attempted to build a studio in a barn in Baambrugge. This was, unsurprisingly, a near-total disaster. The equipment sparked, stalled, failed, and blew up.

But again, through some small miracle, they recorded an album. Again, Warner initially rejected it, but acquiesced once lead single ‘Sail On, Sailor’ was added as the opener. Holland might have had an unimaginative title, but it was to be the last great record The Beach Boys ever made.

It’s not perfect (did they ever make a perfect record?) but it’s the Boys at their imaginative, delightful best. ‘Sail On, Sailor’, salvaged from an old Brian Wilson/Van Dyke Parks demo, is everything you could ask from a Beach Boys single: a rolling, rollicking good time that makes you want to buy a boat and sail down the West Coast, having adventures on the big blue Pacific. And there’s the three-part suite ‘California Saga’: the middle section has some pretentious narration about an eagle (there’s a line about aviary incest – I wish I was joking) but the first and third sections are lovely paeans to their home state, reflecting on and further writing the Californian myth to which they’re so integral.

Fataar and Chaplin also earn their place in the band, contributing ‘Leaving This Town’, a song with a great big preposterous synth solo in the middle that I can’t help but admire. Carl gives some of his best offerings: he wrote ‘The Trader’, another miniature masterwork that starts as a rock song and segues into a delicate, strangely affecting second half. And he sings one of his most heavenly lead vocals on ‘Only With You’, a beautiful little romantic hymn. And at the end, the whole gang get together (even Brian) to sing ‘Funk Pretty’, a ludicrous guilty pleasure about a sexy astrologer. “And now I look in the paper each day/ Wondering what my horoscope will say”. Indeed.

It was also sold with a bonus disc: a Brian Wilson “fairy tale” called Mt Vernon And Fairway. It’s a set of six tracks making twelve minutes in total, and it features Jack Rieley narrating a story about a Pied Piper with a magic transistor radio appearing to a young prince at night, all over some musical snippets and some very Brian Wilson sound effects. If you were being generous you could call it an interesting curio.

As an album, Holland is terrific. But from a PR perspective, it was neither here nor there. Not a counterculture record but not an oldies record; not a sad record, but not a happy one either. The public didn’t quite know what to make of it: it sold better than “So Tough”, but not much better.

Enough was enough. When the Boys returned to California, Rieley stayed in Holland. Shortly after, he was fired. His attempt to ingratiate The Beach Boys with the counterculture had failed.

Listening to Holland now is a sadder experience than it should be. It’s the last blast of genuine creativity from one of the world’s most creative rock bands, before they descended into lousy covers (1976’s 15 Big Ones), Transcendental Meditation adverts (1978’s M.I.U. Album) and interminable disco experiments (1979’s single ‘Here Comes the Night’ – trust me, you’ll regret looking this up). It’s the last time the Boys were truly themselves.

The Beach Boys were always plagued by an image problem, and from the mid-sixties onwards were always chasing the times. But looking back, it’s clear that they encapsulated their generation’s experience better than any other band. They were children of the fifties, raised by a brutally conservative, Depression-era fathers. They found success in the revolution of rock & roll with songs about teenage romance and fast cars. They spearheaded flower power with ‘Good Vibrations’ and took too many drugs in the Summer of Love. Then they emerged into the seventies weary with crushed dreams and never-ending comedowns. You can look at The Beach Boys and see American history reflected back at you. They’re the Hunter S. Thompson of rock bands.

Perhaps the counterculture of the time didn’t see it because The Beach Boys were too close to the bone. People wanted to see themselves in down-to-earth, politically conscious roots rock, or proggy explorations of time and space. They didn’t like seeing themselves in the defeat of The Beach Boys; the incorrigibly hopeful but inescapably sad music of a band fallen from grace.

In recent years, much of The Beach Boys’ music has been reappraised (correctly) as hugely influential and sorely underrated. But they weren’t just excellent – they were timely. Some bands represented the counterculture, others even led it, but The Beach Boys were living it, warts and all. And, in the early seventies, that was too much for their audience to take. As ever, The Beach Boys just weren’t made for those times.