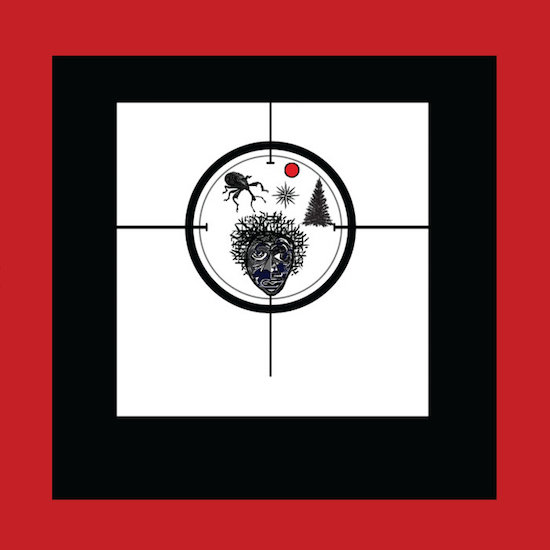

Contrary to dominant narratives, history never ended and racism was never a thing of the past. Today this might seem painfully obvious, if not frivolous thanks to the wonderful 2020, a year that has jumpstarted things into burning global overdrive. Even those who have spent the past several decades anesthethised by the blossoming, meritocratic status quo, bemoan the oppression and injustice. Oblivious to the fact that the sensed absence of inequality was nothing more than a hypnagogic, soporific illusion. Now, with the voices of the persecuted briefly amplified, it’s easy to get carried away, to think of this instant as a crucial point of illumination after which nothing can or will ever be the same. But Chicago’s enigmatic ensemble ONO, who have been around on and off for four decades, warn us otherwise. If we look closely, the experiences of their vocalist, frontperson, and performance artist travis reveal testaments to countless similarly crucial moments. Ephemeral sparks of the many times liberation has been dreamt of, only to be pacified into submission.

Red Summer, named after the period of anti-black white supremacist attacks in 1919, thus exists on the edge of a breaking point. As if a mind confronted with the continued (meta)physical violence towards black people splintered its own reality in which 1619, 1919, and the present overlap. It is an abstract, bizarre vaudeville of eternal strife. Like the band’s composer and multi-instrumentalist P. Michael Grego revealed in an interview to The Wire, it’s “a show meant for and put on by people who are insane, a litany of atrocities that are going on.” Under his baton and with the help of an array of musicians, fragments of heavy industrial noise find footing in funk, gospel, jazz, post-punk, techno, weaponised ambient soundscapes, and anything in-between. Idiosyncratic and anachronistic, this music is not of any time or form in particular. Rather, it belongs to a continuum – an endless thread of pivotal, different but same moments – in which the struggles and merry auctions of the first slaves in America depicted on the carnivalesque ’20th August 1619′ live forever alongside the deviously funky ‘I Dream of Sodomy’ and travis’s memories of abuse in the military.

And while the substance of ONO’s music is only faintly defined – euphonic flutes clash with richly textured machetes and slither through abrasive pockets of hardness – the messages travis delivers have a matter-of-fact quality, even when absorbed in his surreal histrionics. Like on the glorious ‘Syphilis’, a Zolian, naturalistic recounting of the horrifying Tuskegee syphilis experiments that went on from 1932 to 1972 and saw black men become unknowing guinea pigs. “In 1932, Herbert Hoover gave me syphilis / In 1961, John F. Kennedy gave me syphilis,” travis sings mockingly against crawling dub, but with a straight face, a mask hiding his pain and anger. All presidents are complicit and denounced. Their decades of guilt and exploitation hazed by sarcastic steel guitars and saxophones, turned into morose melodies, into condemning sound.

The feeling of Red Summer is ultimately painted whole in this viciously satirising palette, where each song becomes a monument to suppressed and oppressed histories. And as there is no conclusion, the floating baritone gospel of hanging ‘Sycamore Trees’ doesn’t actually sound like a closer, but a feverish awakening. A warning of what happens when we forget. Against pacification and hoping for a momentum of real change.