Sparks portrait by Anna Webber

Every child, at some point, learns the tale of The Blind Men And The Elephant. In the ancient Indian parable, a group of blind men encounter an elephant for the first time, never having heard of this strange animal and having no concept of its form. They each investigate by touch, feeling only one part of the pachyderm’s body. The first, whose hand touches the trunk, decides the creature is a giant snake. The next, feeling the elephant’s ear, assumes it is a bird with leathery wings. The next, feeling its leg, believes it to be a tree trunk. The next, touching the animal’s flank, thinks it is a wall. The next, feeling its tail, insists it must be a rope. The last, touching the elephant’s tusk, declares that it is a spear.

Sparks are the Blind Men’s Elephant of pop history. Most people’s concept of the Mael brothers’ improbably varied five-decade career of art-pop genius and their intimidatingly enormous body of work is inevitably informed by their first point of contact. Very few, outside their devoted fanbase, have a sense of the bigger picture.

To Californian scenesters of the early 70s, they’re the two Anglophile oddballs from the UCLA film faculty who, under the name Halfnelson, somehow persuaded Todd Rundgren to produce their debut, which bemused and bombed when Albert Grossman’s Bearsville label put it out. To British pop kids of the mid-70s, they’re the Transatlantic interlopers whose falsetto lightning bolt ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us’, held off the top only by The Rubettes’ ‘Sugar Baby Love’, kicked off a string of hysterical art-glam hits, and who then took a sharp left turn with the marching band/Charleston/string quartet vintage stylings of the Visconti-produced Indiscreet. To slightly younger Brits whose formative memories are the late Seventies, they’re the bizarre and slightly intimidating pair who hooked up with Giorgio Moroder and bounded into the Top Twenty via the groundbreaking electro-disco of ‘The Number One Song In Heaven’, accidentally inventing every synth duo of the decade that followed.

To French or Australian music lovers of the same era, they’re guys who broke into the Top 20 with the ambiguously smooth ‘When I’m With You’. To American audiences of the Eighties, they’re the intriguingly idiosyncratic act who surfed the New Wave with Jane Wiedlin duet ‘Cool Places’ and their own ‘I Predict’. To Germans of the Nineties, they’re the band who made the Top Ten with the elegiac synthpop of ‘When Do I Get To Sing "My Way"’. To Meltdown-goers lured in by Morrissey’s blessing, they’re the creators of the hugely original digital opera Lil’ Beethoven. To Swedish aficionados of musical theatre, they’re the composers of a counterfactual opus in which Ingmar Bergman is enticed into selling out his artistic integrity to Hollywood. And to 21st century indie rock consumers, they’re those two peculiar old guys who hooked up with Franz Ferdinand that time.

Nobody is entirely wrong. Nobody is entirely right. The only thing that’s certain is that more and more people are becoming interested in exploring the Maels’ oeuvre. Sparks’ most recent album, 2017’s Hippopotamus, achieved their highest chart position since their 1974 breakthrough Kimono My House, and their new one, A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip, helpfully covers most Sparks styles, making it as good a gateway drug as any. Later this year, a feature-length documentary film by Shaun Of The Dead/Baby Driver director Edgar Wright will doubtless provide a rounded overview to newcomers. For now, here are ten entry points to Sparks’ universe, chosen by tQ but narrated by the Maels themselves.

Like Gilbert & George, to whom they are frequently compared, the brothers have a quiet understanding and a mutually-complementary interview dynamic which is long-established, and which mirrors their performing personae. Singer Russell, of the puckish charisma and octave-vaulting voice, does more of the talking. Songwriter and keyboardist Ron, of the Chaplin moustache and dapper demeanour, mainly keeps his own counsel but makes timely and pithy interventions.

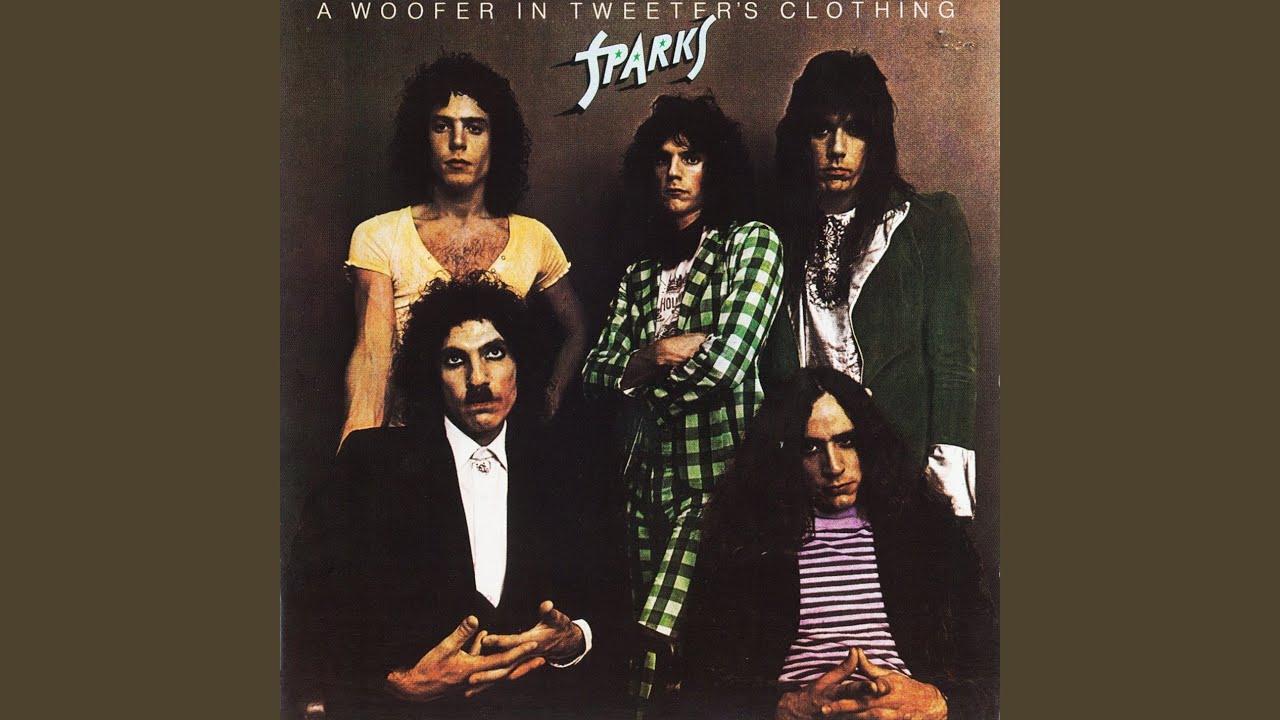

A Woofer In Tweeter’s Clothing – album (1973)

If people explore your catalogue in chronological order, do you enjoy imagining how confused they’d be at how different an album like A Woofer In Tweeter’s Clothing, the first under the Sparks name, sounds from the more famous records?

Russell Mael: Yeah, it’s probably pretty hard to get one’s head around the fact that it’s the same band. We think of that as one of our strengths. For us, it’s always a case of reinventing how we place my singing and Ron’s lyrics and melodic stance when he writes, how to continually find fresh ways of presenting that. And so an album like Woofer is completely different, at least in my mind, to Kimono My House. It’s not a conscious thing, we don’t have a board meeting to discuss how we can put what we’re doing into a new context each time, but it’s just something inherent in us when we work that we just have this need to be doing something fresh. Also, the circumstances surrounding any one period change, and that also helps to influence change between the records over any given time.

In another sense, there really isn’t that much difference, even though we’re trying to make it different from our end, just because the sensibility is continuous through everything we’ve done. It’s not something that we can even do anything about. People can kind of see a thread through everything we’ve done. We’ve been through changes, but the core of what we do remains since the very beginning.

When you recorded Woofer you’d already made one album, as Halfnelson, with Todd Rundgren. What was he like to work with?

Ron Mael: We actually really love that album. We’ve said it before, but it still holds true that if it weren’t for Todd Rundgren there may not be any Sparks now, or may never have been a Sparks. Because he was the one person that saw in those initial demos something that no-one else in a position to sign the band saw. We gave tapes to everybody, and got the polite rejection letters back. And then, the one last hope, on a whim, we said "Let’s send it to Todd Rundgren." And the tape was the same pretty eccentric album in its own little world that we sent to everybody else. But Todd said ‘This is really brilliant and I want to produce it.’ And that is mind-boggling, when everybody else tells you, ‘No, that’s not how you make a record,’ and then Todd Rundgren says, ‘That is how you make a record, and I want to be involved.’ We owe everything to him.

Did you keep in touch?

Russell: There’s a documentary film being made by Edgar Wright about Sparks, and we had the good fortune that Edgar approached Todd. We hadn’t seen Todd since the time of those albums, that A Woofer In Tweeter’s Clothing and Halfnelson period, for no reason at all, just our paths didn’t cross. And in making the documentary there was a really cool surprise that Edgar hooked us up, both sides not knowing we were going to be meeting and be filmed for the documentary. So, after X amount of years, X amount of decades, we reconnected with Todd. It was really heartwarming to see was that he was the same guy we remember from 1972. And I think it was mutual. The spirit from both sides was still intact, and it was so good to reunite.

And then on Woofer, it was James Lowe, from The Electric Prunes. Were you fans of his?

Russell: Yeah, I loved ‘I Had Too Much To Dream Last Night’. An incredible song from that era that still sounds really good to me. James was Todd’s engineer for for the longest time, and then Todd got busy with other projects and touring and stuff, so he asked if we would continue on with the next album and have James Lowe produce it. James was a great guy and a really good engineer, so it was a good experience.

Also, later on I read that he was so disheartened after A Woofer In Tweeter’s Clothing didn’t become a No.1 album, because he genuinely believed that album was like a Sgt. Pepper’s, and that album not doing what he thought it would do commercially just made him want to get out of the whole music industry. So he had stop doing stuff for a while. He kind of lost faith in his own taste, and in what he thought should be an album that reaches the masses. So maybe we were all delusional. But you always feel that with the right circumstances, an album like that can reach a bigger audience, and just at that time it didn’t work.

There’s a cover of ‘Do-Re-Mi’ from The Sound Of Music on there. People must have wondered what the hell you were doing.

Ron: Well, that was only one thing to kind of throw people. I think that everything we were doing was throwing people. So it was almost natural that we would do a song from The Sound Of Music. It wasn’t that song that people were scratching their head about. People were scratching their heads about everything that we did, so it almost seemed a natural fit to be honest.

This album led onto your appearance on The Old Grey Whistle Test and a residency at the Marquee in London, making this the beginning of Britain falling in love with Sparks.

Russell: Yeah, the label thought that we could reach a wider audience because the sensibility was going to be more in tune with a British audience. So they shipped us off to the UK, and we had that residency at the Marquee and then people started coming out to see the band, whereas in LA we had a much smaller audience. That residency led to Island Records wanting to work with with us, but with the provision that they wanted us to reform the band with British musicians around Ron and myself. They really liked the songwriting and the singing and the whole sensibility, so they proposed that we set up shop with new musicians and make a go of it in the UK. And for us that was like a dream come true, because we were such Anglophiles, just to get to finally be a ‘British’ band, in a certain sense.

‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us’ – single, from Kimono My House (1974)

Most British people’s way into Sparks is ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us’. In a sense, it’s a good first contact, because it’s a perfect example of a thing that Sparks do, which is to take someone’s inner thoughts and inflate them to epic life-or-death scale. In this case, just a guy getting ready for a date, but in his head it’s a Wild West shoot-out and it’s nuclear war.

Ron: Well, I think that’s a good observation. Because I think what we’ve always tried to do, in a lyrical sense and then putting it in a musical context, is take ordinary situations and channel them in ways that you haven’t heard before. And kind of exaggerate the emotions of things. We were thinking in cinematic terms. Not necessarily cinematic in sound, but the idea of over-accentuating things, both in the lyrics and the music. So there’s that mundane situation that you start with, in ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us’, and then you’re kind of blowing it up. That is something that we try to do in quite a bit of the music: making things over-dramatic. And you’re kind of wondering "This isn’t a statement about some enormous world issue. This is a personal situation. Why isn’t this just being done in a folk song?" That runs counter to our nature.

That song was the impetus in the UK for Sparksmania: screaming fans ripping Russell’s clothes off, band members getting hospitalised at gigs, and so on.

Russell: I have nothing but good memories of that period, being thrown into the whole music scene in Britain. It’s all intertwined for us with living in London and then having a huge hit song and then being on Top Of The Pops every other week for a long period of time. It was just such a unique situation for us, kind of overwhelming, and so completely opposite to the experience we’d had up till then in LA . It was mind-boggling. The variety of types of people that were coming to see the band in concert, the screaming girls on one hand and then all the art students and more intellectual types coming out, and throwing those two elements together in one concert setting…

It was like both sides couldn’t understand what the other was seeing. It was fascinating seeing that screamy reaction, because nothing had changed stylistically in the lyrics that Ron was writing. We were singing about, you know, Albert Einstein and stuff, and that’s eliciting screams from young girls! And it kind of does your head in when there’s that sort of disparity, when the visual side of the band, the personality of the band, is equally strong to the lyrical and melodic content, and how that’s presented. So all those elements are almost going counter to each other, and the audience was this disparate group of people. But it was an amazing experience.

Does it kill you a little that ‘This Town’ only reached No.2, not No.1?

Russell: Yeah [laughs]. Well, if we had lost out to anybody else, I dunno, Roxy Music, at least you’d go "OK, well, they’re cool." But to lose out to The Rubettes… I mean, come on.

Indiscreet – album (1975)

After the success of Kimono My House and Propaganda in 1974, Indiscreet the following year was a risky swerve into different territory. Produced and arranged by Tony Visconti, it drew upon 1920s-1940s styles.

Russell: We obviously loved all the work Tony Visconti did with T. Rex and David Bowie. And there are different kinds of producers. There are ones that are tastemakers, who push a sensibility onto the projects they do. Then there’s producers that are also really musical. And then ones that are technical, like engineers. And those things aren’t always there in the same person. But with Tony, you got everything. He’s an amazing musician, for one, and his taste in pop music is so in line with our sensibility, and he’s also just an amazing engineer.

So with all those things, we thought that this album, where we wanted to try to inject some outside arrangements into Sparks and to open up the sound and make it not necessarily a five-piece band, but to augment what we were doing with marching bands and orchestral stuff and string quartets, Tony was just going to be the best guy to interpret that. He’s the type of producer, again like Todd Rundgren, who encourages your eccentricities. He’s not the type that says, ‘Guys, let’s maybe tone it down a little bit.’ He’s the exact opposite.

So when Ron had written ‘Get In The Swing’ and we said, ‘We’d really like to try this with a marching band, and have tempo changes throughout,’ and it’s a pretty complex song even though it’s kind of jolly, Tony really took it on as a challenge. There’s also ‘Looks, Looks, Looks’ which was trying to use big band-era orchestration, and all you had to do is say to Tony, ‘This is the thing we’re looking for,’ and you knew he would be able to orchestrate it to be authentic for that sound. So we still have so much respect for his productions and his taste.

Ron: We were lucky to be able to work with him twice again after that. Once in collaboration with the French band Les Rita Mitsouko, and once for the Plagiarism album, where we again wanted to use orchestrations on some of our songs.

No.1 In Heaven – album (1979)

If an arthouse rock act teamed up with a dance producer now, nobody would bat an eyelid. When Sparks did it, at the height of the Disco Sucks movement, it was almost unthinkable. But No.1 In Heaven invented every synth duo who followed in the 80s.

Russell: Up until that time, everyone assumed Sparks was a band where the format is guitars and bass and drums. And then when we made this decision to try to work in a different format, and to base what we were doing in an electronic environment and to have Giorgio Moroder produce that album, a lot of people, critically, said we were being blasphemous to the rock cause. We never felt that we were in a rock cause, and all we had was a Sparks cause. And whatever direction that would lead to, that would be what it would be. Critics were just puzzled, and when negative things said about the album, it was kind of like "It’s disco music!", you know ‘disco’ in the pejorative sense.

First of all, we never thought of that album as a disco album. We thought it was just something in its own area, a lot more beat-driven, but we never thought in terms of disco or not disco. We don’t see things in those terms. We just thought was going to be a bold album in this electronic format, and the change was that we were now working as two people instead of a traditional band of five or whatever. Which was confusing to some: "How can you be a band any more if there’s only two of you?" But we thought that the studio can take up the slack, and be the rest of the band. We didn’t see anything restrictive about working as a duo. The only downside at that period was that we weren’t able to recreate that sound live, because it was all done in a studio with tons of massive Moog modules, so it was just kind of prohibitive for us to tour. But we never, in our career, thought about how you can perform something. We always just went at making the best possible album we could make, and then after the fact we would figure out how you tour with that.

The other odd thing about that album is that the public embraced it to such a big degree, when a lot of critics were just befuddled. That album had three three songs in the UK charts. So it was a situation where the public is willing to embrace new and challenging ideas, if it’s exposed to them. Virgin Records just loved that album and thought it was something special, so they really helped to promote it and to give it a platform. And then, once it was heard by the public, ‘Beat The Clock’ was a really big hit, and ‘Number One Song In Heaven’ also.

In a Melody Maker interview at the time, you said "Just wait six months from now, and watch all of the New Wave synthesiser disco bands, which will be popping up and disco music becoming very respectable in hip circles, and then somebody else will capitalise on what we’ve done." You were right, weren’t you?

Ron: Occasionally we are! It’s funny that we thought that at the time, because it probably was just purely defensive on our part where somebody was trying to slag us for doing that, and we said, ‘Just watch,’ but not really believing it. And all of a sudden that actually did happen.

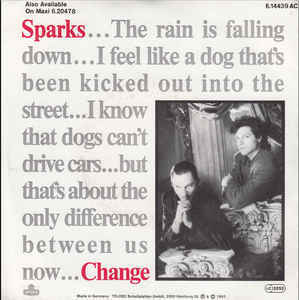

‘Change’ – single, from Music That You Can Dance To (1985)

While Sparks-influenced synth duos erupted throughout the 80s, Sparks themselves were relatively invisible in the UK. Which made it all the more startling when they turned up on primetime BBC1 to appear on Wogan performing ‘Change’, a mini-motion picture in pop song form, which switches between Russell’s downbeat, downtrodden Film Noir monologue and epic, sweepingly cinematic choruses.

Russell: It’s one of those songs where sometimes we just want to try to do something that’s going to shake up listeners, to have a response. Because the worst thing is people just having no opinion whatsoever. We like to do things that are stretching the genre as much as you can, and that song I think is one of those examples.

Ron: It was the first time we’d really used sampling. We recorded it in SynSound in Brussels with a couple of our friends from Telex, and a lot of it was done on a Fairlight which, at the time, was basically a $100,000 sampler. Now it probably comes with any Mac. But it was such a novelty for us, and so we as usual went kind of too far, sampling everything available, because the whole idea of rights issues wasn’t even something to be concerned about. We just went crazy with all of that, which helped to give that song a lot of variety and ambience that we wouldn’t have been able to do if we were just recording it as a band. We sampled lots of cellos and stand-up basses, and percussion crashing away. There was a record chain located in Brussels and we would go down there and come back with all these records, and just take individual instrument sounds and then play them in ways that fit our aesthetic. Whenever there’s a new piece of equipment, we kind of overuse it.

‘When Do I Get To Sing "My Way"’ – single, from Gratuitous Sax And Senseless Violins (1994)

In which the singer, looking back on ‘those Crackerjack years’ of their fleeting glory years, wonders when they will ever receive the lifetime-achievement accolades and grand curtain-calls they deserve. Listeners in Germany, where the song was a major hit, must have been confused. These, surely, WERE Sparks’ glory days.

Ron: We had a German manager at the time, and we always like to think that the lyrics are having an effect on people as well as the music, so after that song became really popular, we asked him "What percentage of people really understand the lyrics to that?" and he said, ‘Maybe 10%.’ So it was one of those songs that I think got across to the German public in an emotional way. Maybe that’s really inspiring, where it isn’t a specific lyric but a general feeling of the song that really captivated people. And in a certain sense it’s more flattering that it was that, and not just a specific lyrical image.

It’s a rare case of a Sparks song which can be read as autobiographical.

Ron: Yeah, I mean obviously most people feel like they’re in that position of ‘When is that moment going to come when I’m recognised?,’ and probably in a subconscious way there is an autobiographical element, though maybe not a large one. It came through with those lyrics.

Lil’ Beethoven – album (2002)

Based largely on repetitive phrases and loops on tracks like ‘The Rhythm Thief’, Lil’ Beethoven stands apart from anything else in Sparks’ oeuvre, and proved that even relatively late in the game, the Maels were unafraid to take risks.

Russell: There were a bunch of songs Ron had written, but we just weren’t that excited about doing another album in a traditional setting. We weren’t inspired by ‘songs’ in a traditional sense. So we just said, ‘What if we approach this album by getting rid of things that are normally part of the rock format of bass, guitars and drums, and just try to substitute something?’ We didn’t want a soft album, an acoustic album. We wanted to find a way of having the sound be equally as aggressive as if you’d had rock guitars. So we thought we’d try eliminating guitars, drums and bass, and see if we could replace them with really aggressive strings and really aggressive vocals, taking the place of the power that all those instruments would normally bring. So once we’d got into that mindset, it became really a fun challenge to see how you can push it, to keep coming up with ways of keeping the power but without all the rock ‘givens’ that a band is supposed to place in their music.

In ‘Your Call Is Very Important To Us, Please Hold’, there’s another example of Sparks taking an everyday situation – being on hold on the telephone – and amplifying it to an absurdly melodramatic level.

Russell: Yeah. I like that in Ron’s lyrical writing. ‘Your call’s very important to us but please hold" ‘which everybody’s been through, but then taking that, and by the repetition of it in this piece, all of a sudden elevates that whole concept till it almost becomes an opera unto itself. And then that pre-recorded voice you get when you phone some company takes on a whole new meaning. It’s similar to ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us’, in that it’s this incredibly mundane situation, but when you hammer it for three and a half minutes and in the context of how it sounds musically, it takes on a whole other life.

The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman – album (2009), musical (2011), film (TBC)

The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman is one instance of Sparks’ occasional tendency to launch ambitiously grand projects beyond the traditional pop format. Originally an audio piece recorded with Swedish broadcaster Sveriges Radio, it transferred to an English-language musical theatre production in Los Angeles 2011, and there is now talk of a film adaptation. Meanwhile, another Sparks-written film, Annette, is due this year.

Russell: For the Hippopotamus album we had a video done by a British animator named Joseph Wallace for ‘Edith Piaf Said It Better Than Me’, an almost Eastern European-style puppet animation, and his technique is really beautiful. So, how we’ve been pursuing The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman is to try to get this off the ground as a feature-length film but done all in puppet animation. It would be really beautiful on one hand, but it would also overcome some of the limitations. Because there’s some pretty big scenes towards the end of the story, almost battle scenes where Ingmar Bergman is trying to escape Hollywood, and it becomes suddenly like a big-budget action film. So we thought one way of being able to portray that, and for it to be as fantastical as we want, would be in puppet animation style. And then anything could go, and it could be as elaborate as we wanted, whereas with live action we might have some budgetary constraints.

The impetus of doing a narrative project like The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman led to our doing the Annette project, which is now finished as a full-blown movie musical with Adam Driver and Marian Cotillard. Doing The Seduction Of Ingmar Bergman showed us that we really loved working in a narrative format, and so we did that again with Annette, which we initially thought was going to be Sparks’ next album. And then one thing led to the next, and we presented it to Leos Carax, the French director, and he said "Wait a minute. I want to direct this." And that detoured it into a whole other area, which we’re so happy with.

FFS – collaborative album and tour (2015)

The FFS collaboration with Franz Ferdinand was a critically and commercially successful collaboration. But the world Sparks create around themselves is so distinctive, and so particular to them, that it’s surprising that the Maels allow outsiders into that world relatively often.

Russell: Obviously it has to be the right circumstances, and we felt that with the FFS album that it would be a really unique project, working with with Franz Ferdinand with their sensibility, and with ours, and combining the two bands. I can’t think of too many other instances of complete bands merged. So it really took a lot of desire on behalf of both bands to want to carve out two years of both of our lives to make this happen. It started a little bit gingerly at the beginning. We said, ‘Maybe we’ll do one song together,’ and then, ‘Why don’t we make this an album?,’ and then, ‘You know, if there’s an album we really need to tour, too.’

To have two bands who have their own strong vision of what they want to be doing, to unite over this long period of time, was a pretty big undertaking. And it worked both ways where Sparks were able to be introduced to a whole other audience with Franz Ferdinand’s fans and vice-versa. We’ve collaborated with other bands, like working with Les Rita Mitsouko, and even with Faith No More for a couple of songs on the Plagiarism album, and since then kept in touch and, on occasion, gone on stage with them for encores and done ‘This Town’ together and stuff.

A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip – album (2020)

Every new Sparks album will be, for someone, their first.

Russell: That’s a huge motivation for us. We’re hoping that new fans will be attracted to the band, and will be curious enough to listen to what we’re doing. And then, if this new album is not the absolute strongest thing that we could be doing at this time, then we’ve failed. The one thing that keeps us motivated is that we want to keep expanding our audience. We’re hoping that people will just discover the new album on their own, and say, ‘What? God, this doesn’t sound like a band that has 24 albums.’ And it gets harder and harder to keep coming up with ways to approach a new album that you hope are going to be fresh and vital and provocative, because when you’re working within the confines of pop music, there’s certain given limitations or parameters. We hope that we we’ve done that with with the new album.

Ron: It’s more that in our minds, when we’re working on a new album, we approach it as the first album we’ve ever done. If you’re too aware of who may be listening to the music, you may be tempted to gear it toward those people or water it down for a new audience.

This record is a good ‘way in’ to Sparks, as it covers several Sparks bases: rock, electronica, a bit of disco, and operatic moments…

Russell: I think A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip is a good introduction to Sparks, yeah. Because it’s one of those albums that’s all over the map sonically, and lyrically it’s really kind of uncompromising too. It’s not timid in any way. For the label or us or anyone involved with the band, it was difficult to figure out which songs would be put out initially. Everyone had a different opinion. Because stylistically the album is really varied. And so, when people would hear one of the songs first, they’d make a judgement based on that, "I see, it’s going to be that kind of album", but it really isn’t. There wasn’t a song that was typical of the whole rest of the album. But it’s kind of a blessing. We think of that as a really positive thing that when people finally get to hear the entire album, I think they will be surprised at the depth and the expansiveness.

Ron: I don’t think it matters about the scope of the styles, only that it is a strong album. For a lot of people, the No.1 In Heaven album was a good way in, and that was one style.

‘One For The Ages’ revisits the theme of ‘When Do I Get To Sing "My Way"’ a little, although it’s about an author, not a singer. "When the statues come, hope they look like me/When the prizes come, I will look to be humble in my speech/Basking in applause…"

Ron: Yes, I like songs about dreams of a better future.

Russell: The sentiment is this guy who’s got his job at this accountancy firm, but thinking that he has more inside of him than just this robot-like job, and on the side he’s trying to come up with this work that will launch him out of this environment that he’s in, and thrust him into something that’s more satisfying. So, in a similar way, yes it’s somebody striving for something beyond what they have now in their life.

It feels slightly shocking to hear you swear on this album, like "Please don’t fuck up my world" or "put your fucking iPhone down and listen to me". Because you’ve always been such a genteel band.

Russell: Yeah. Sorry about that! We toyed with toning down that word, and asking, ‘Could you kindly set your iPhone down’ or some other way of phrasing it. But it’s such a colloquial way of speaking now, so much a part of everyone’s vocabulary, that in a certain way it didn’t sound like it was being so profane. But also we just felt that there was no other way to get across the point but, ‘Put your fucking iPhone down and listen to me.’ That whole concept of people not communicating with each other any more, and using the iPhone as a metaphor for that. But it also references Adam and Eve, and Abraham Lincoln and various situations throughout time where there’s been a lack of communication in people’s lives.

Ron: We may adopt a genteel manner when we speak with journalists, but most of our music and lyrics have always had a strong underlying sense of hostility. This hostile nature I think is the key to driving us to do this sort of music for so long.

A few lyrics seem astonishingly prescient about the COVID-19 world. There’s a moment in ‘Sainthood Is Not In Your Future’ where the phrase "all interaction’s now suspended" gets repeated. And the whole of ‘The Existential Threat’, with lines like, "The existential threat is drawing very near… I paid the whole bill because insurance won’t, they just won’t cover existential meds… Let me hide just until the danger passes, then I’ll go outside…" It’s like you saw this coming.

Russell: Oh God. Obviously everything was written before the current situation, but it’s been pointed out to us that yeah, it was certainly prescient on Ron’s part. Even the one that you brought up, about all interactions now suspended. I hadn’t realised that. Oh boy. Sadly, but yeah, some of the lyrics have taken on a new a new context over time.

RON: Sadly, some of the songs pertain to the current situation in ways that we never envisioned. Ah well.

A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip is out now. Annette, and Edgar Wright’s untitled Sparks documentary, will follow later in 2020