Credit: National Institute of Design Archive, Ahmedabad

In 1958, Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first post-independence Prime Minister, invited the progressive US designers Charles and Ray Eames to make recommendations for a new programme of training in design, as the country considered a bold future after freeing itself from British rule and considered, as the Eames put it in their introduction: “what India can do to resist the rapid deterioration of consumer goods within the country today.” Following the publication of their findings, The India Report, in 1961 India’s first National Institute of Design was founded in Ahmedabad.

Although funded by the sponsorship of American organisation The Ford Foundation, the NID was headed by the Sarabhai family. Siblings Gautam, a mathematician, and Gita, a musician and architect who had trained with Frank Lloyd Wright, were particularly important. Although wealthy industrialists, they were radicals. They were close friends with Gandhi and inspired by his ideas of alternate education models – as well as Bauhaus’ principles of learning by doing. Gita had formed a lasting friendship with John Cage during her time in America in the 1940s, and the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Alexander Calder and Iannis Xenakis were visitors to their home.

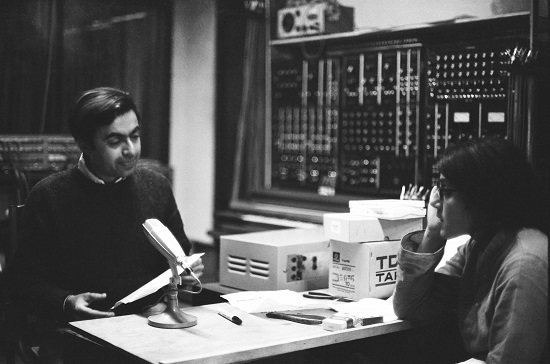

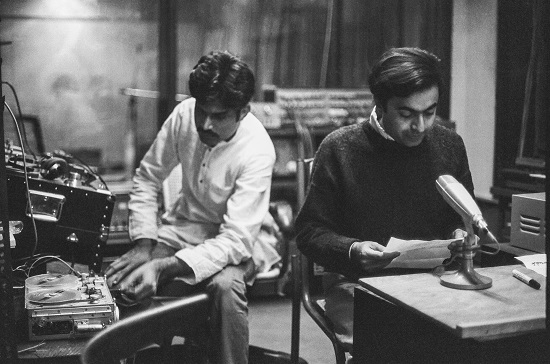

Their most important guest, however, was the experimental musician David Tudor, who spent three months in 1969 taking workshops on the emerging art form of electronic music. With him he brought a Moog synthesiser – then the only one in all of India. Together with his students he recorded tracks that are as innovative, ground-breaking and magical as those produced in more celebrated Western hubs like the GRM in Paris or the NWDR studio in Cologne, but that have since been largely forgotten.

In 2018, however, investigating an article he’d read by the journalist Alexander Keefe about the Institute, British-Indian electronic musician Paul Purgas stumbled across some 25 hours of tapes, dating from Tudor’s workshops until 1973, in one of the Institute’s cupboards. Staggered by this newly-discovered pinnacle of early electronic music, he investigated further, and tells this criminally-overlooked story in a new radio documentary, to be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 this Sunday evening (May 17). It is a wonderful, warm, and eye-opening documentary, but also a bittersweet one. The NID never achieved the lasting legacy of its Western counterparts, the documentary explains, because of a number of factors – among them the country’s shift from optimism to anxiety in the 1970s, the personal misfortune of its composers, and the way in which it narrowly missed the establishment of a national Indian TV station which could have given it a status akin to The Radiophonic Workshop.

Photo courtesy of Paul Purgas

However, it is also the start of a longer project that aims to establish that long-overdue legacy. At the end of this year Purgas will present an exhibition called ‘We Found Our Own Reality’, which will feature a soundwork that makes use of those tapes, and he’s currently working alongside the NID to find a way for the full archive to be released sensitively, and to be made available in its entirety online.

To find out more about the extraordinary story of the NID and the birth of Indian electronic music, tQ caught up with Purgas via FaceTime. His documentary ‘Electronic India’ is on BBC Radio 3 on Sunday, May 17 at 6.45pm, and will be available shortly after broadcast here.

tQ: Do you think it’s too simplistic to directly compare the National Institute of Design to, for example, the Radiophonic Workshop, the GRM in Paris, or the NWDR in Cologne?

Paul Purgas: I think it both is and it isn’t. It does feel from what I’ve discovered so far to be like point zero for electronic music in India, that feels quite certain, and it did have parallels to the Radiophonic Workshop in that it had an applied sense to it, it was being put in the service of animation, radio jingles and government training information. At the same time the thing that makes the National Institute of Design quite unique within the international birth of the electronic music studios is that it wasn’t inside a TV station, it wasn’t part of a musical recording studio, it wasn’t part of a conservatoire or a music institution, it was part of a design school, and that makes it quite an anomaly within that moment.

In the same way that in Germany, the early Krautrock musicians were the first generation to have been born and come of age post-Nazism, the Indian musicians working in the National institute of Design were the first truly post-independence generation. Do you see a connection between Indian independence in 1947 and the experimental music that came two decades later, and do you see parallels with what was happening in Germany?

I think there’s a really amazing parallel to make between those two national iterations of electronic music, because those years post 1947 there was this moment of Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of reimagining the country post-independence. There was a really beautiful scene that emerged in some of the conversations we had while making the documentary, this idea that at that moment India was still dreaming, there was this sense of a possibility of imagination, a utopian set of ideals and ideologies that were emerging around shaping India post-independence. The National Institute of Design emerged out of a document called The India Report which was this incredibly radical attempt to introduce design as a tool for shaping a new industrial India. The National Institute of Design studio emerges within this dream, it emerges to almost give voice to that moment. Across the tapes there’s people discovering electronic sounds for the first time, in a way that’s so incredibly free from baggage, an attempt to almost redefine or rebuild their own history from this point zero. There’s definitely parallels between the two for sure.

And then in the late 1960s and early 1970s I get the impression that this utopian dream dies away. Why was that?

The National Institute of Design itself was being supported by American money through the Ford Foundation, and there had been a desire internationally to help support India in building new modernist principles. However towards the beginning of the ‘70s there was the emergence of the India-Pakistan war. Nixon chose to side with Pakistan during that conflict and that seemed like almost a critical moment in the collapse of American-Indian relations. Simultaneously, India at that time was coming to terms with the aftermath of the Indo-Chinese war, and also Nehru’s death.

There’s a lot that’s happening in that moment that creates a shift in the national consciousness, looking less to the possibility of the dream and more towards this sense of a kind of emerging realism about how India was going to define itself. Questions were asked about whether the arts and radical practise could really do anything in service of the nation. In the 1970s the Sarabhai family, this radical, incredibly forward thinking and visionary family that founded the National Institute of Design, brought in a former Navy admiral to oversee the institution. Suddenly there was this meeting of worlds that were never going to be compatible.

Credit: National Institute of Design Archive, Ahmedabad

The documentary is really bittersweet, particularly when you speak to Jinraj Joshipura, the last surviving Indian composer on those tapes. He was offered a scholarship to study musical synthesis at the Rockefeller Music Research Center in San Diego, but his father wouldn’t let him take it. It feels from the ideas that he had as if he could have been a truly pivotal figure in electronic music had he gone…

It’s heart-breaking when it’s laid out like that, when you realise that this could have been such an amazing voice and an amazing contribution to music history. Jinraj was around 19 or 20 when he was offered the opportunity to go and study with the support of the Rockefellers in America, and to do incredible research into things like underwater sound…

And to see whether he could use electronic music to communicate with animals?

He had this very beautiful Hindu holistic idea of electronics being able to interface with nature and connect to nature. It was a strange thing speaking to Jinraj because I had exactly the same situation of not going to art school but going to architecture school in order to have something vocational that an Indian family can understand. There’s a sadness to Jinraj’s story, but also there’s something quite beautiful about it because after all this time he’s starting to return to music. I’ve started conversations with Moog about creating a situation where he can return to sound and electronic synthesis. There’s something I think that’s incredibly powerful about the way music’s a thing that never truly leaves us. We might drift away or lose contact with it, but it’s never gone, you can always return.

Tell me about the first time you heard the tapes?

There was a massive build up to it, when I first found the tapes I didn’t actually play them, I went back to the UK and taught myself about tape conservation and how to use reel to reel players. But that first moment of getting to hear them was total magic. There were tapes by David Tudor that were in the collection, so it was exciting to hear David Tudor works that had never been known of or catalogued, but simultaneously to hear the work of the five Indian composers for the first time was totally mind blowing. It was literally like hearing a whole new branch of the history of electronic music for the first time.

Have you considered trying to release them?

At the moment I’m speaking to the National Institute of Design about ways in which we can work with the copyright in order to get them out into the world – I feel from a personal perspective that it needs to be done in a way that is absolutely fair and that acknowledges and pays its dues to the context in which it emerged from. I’m trying to make the archive as accessible as possible. That was my central interest, because this is such an important part of international music history and specifically Indian music history. My hope is that it can become a free and open resource for Indian musicians to learn about this moment of the NID, and hopefully work with the material themselves.

The documentary also goes into this newly emergent scene of young Indian electronic musicians, tell me more about them.

There’s certain projects emerging in India, Listening Rooms, for example, and Synth Farm, these quite grassroots enterprises for distributing and creating platforms for musical performance and education. There’s a lot of incredibly committed people in the scene now that are starting to work in this very community-spirited way about building an electronic music infrastructure across the country. It feels like, once again there’s dreaming and an amazing amount of optimism in India about the growth of electronic music. The beautiful thing about this moment is that the level of access is constantly improving, even the likes of musical apps for mobile phones, the tools for making music seem to get more and more refined and more and more accessible. Removing those last few barriers around these esoteric old crafts, to me that’s fantastic.

You talk in the documentary about how when you were growing up rock and guitar music felt very white and exclusive, whereas dance music felt more accessible for you as a British Indian. What do you think it is about electronic music that made it so inclusive?

I was incredibly lucky to see Jeff Mills DJ when I was a teenager, and through that I discovered the whole world of Detroit techno. It was operating on so many levels, plugging into this imaginary potential of music. Within that there were projects like Underground Resistance where it wasn’t even about showing your face, it was about dismantling your identity or kind of retaining anonymity whilst the music was very present and at the forefront. Everything about electronic music, specifically that strand that gripped me, felt like something I could definitely envisage myself in. It’s not like I wasn’t listening to rock music, but I definitely felt more self-conscious to throw myself into that world.

Why do you think it is that the NID didn’t have as much of a lasting legacy as European and American equivalents?

I feel like it kind of emerged just at the wrong moment in time. There were lots of ideas that were encircling the techno-industrial possibility of India at that moment – specifically India looking at building its own TV Station and having a satellite to transmit TV across the whole nation. That was planned in the late ‘60s, but sadly didn’t occur until the almost the mid-‘70s. It felt like the whole NID studio was potentially being developed in a Radiophonic tradition, to create sound for a new national Indian TV station. But because that came so much later, the mood was slightly lost in time.

Paul Purgas’ ‘Electronic India’ is broadcast on May 17 at 6.45pm for BBC Radio 3’s Sunday Feature. It will be available shortly after broadcast here.