Photo: Tim Grey

tētēma is a band consisting of Mike Patton, consummate frontman of Faith No More and Mr Bungle, and polymathic Australian composer and avant garde musician Anthony Pateras. Last month they released their second album together Necroscape. Both are the kind of artists blessed with staggering range and explorative instinct, and when they come together as tētēma their talents do not just combine, they multiply. Necroscape is a corybantic and raging record, a zealous, ambitious, fiery and joyous piece of art that demonstrates the considerable breadth of their powers.

They have been a long-distance project since formation since long before that became the ‘new normal’, and they meet in person on average every couple of years. Due to their respectively daunting work schedules, the record came together primarily through “endless daily emails,” gradually layering and responding to one another’s idisoyncracies until they arrive at a sprawling and twisting epic that plunges and leaps in every conceivable direction. What’s really makes Necroscape so great, however, is that there’s an exuberance that stands out among that tempest of sound.

They revel in their own pomp, but take it deadly serious too. It approaches themes of isolation and technology (again, before that was the theme of 2020), and the potentially dystopic effects thereof, but they swerve the cod-Orwellian turgidity of a band like Muse. There’s no bloat to their music, however huge its ambitions. One half of tētēma, Anthony Pateras, tells us more.

tQ: I hate to ask, but given the record’s themes of isolation in the surveillance age, how are you finding lockdown, quarantine and social distancing in the current situation? How are you handling it all at the moment?

Anthony Pateras I’m totally OK where I am, which is little town in the bush in Australia. Contrary to what our immigration policies suggest, there’s a lot of room here, so distance is not really an issue. In general, I think it’s important to remain positive through this, but I think this outbreak throws a lot of things into relief. Primarily, it would be mad to go on living like we were, which was to place financial profit over humanity and ecology above all else. It’s not crazy to suggest that there’s a direct correlation between the indiscriminate destruction of nature and the indiscriminate deaths of humans. The bushfires in Australia were another version of the same thing.

Photo: Aaron Chua

Can you expand a little on those themes, and how they’re manifested on the new tētēma album?

In a nutshell, I feel the fact that most people live their lives half inside a screen, probably made by a slave, is a very weird thing. I feel the fact that most people have so willingly forfeited control over most of their lives to bunch of self-interested Californian billionaires is a completely insane. I feel the cost of social media is not free; it takes a massive toll on the mental health of everyone who uses it, in turn making them not only anxious and depressed, but extremely distracted and self-absorbed. I feel this has resulted in otherwise intelligent human beings doing and saying stupid and cruel shit to each other like always, but just a lot faster and in public. Lastly, when I’ve been very outspoken about this at various points, I’ve received looks of bewilderment in return, because people say it helps them remain ‘connected’. People were connected before corporations sold our friendships back to us!

I also feel that letting technology do the thinking for you makes bad art, every time. So, on this record, I tried to use technology as a conduit for human impulse, not the other way around. You know, these days, we’re always put in this position of wrestling control back from the machine. Everyone knows this on some level, but nine times out of 10, concede their agency anyway. It’s pretty out. I’m not a luddite, but believe it’s important to remain very selective about the kinds of things we allow ourselves to live our lives and make art with.

So although the album is not really about these things per se, it certainly colours my perspective on things. We have live-streaming of racist massacres as a new social norm, you know? In that scenario, I try to make a positive response to a bad situation, and that response is Necroscape. You have to laugh in the face of dystopia, otherwise there’s no point.

How did you and Mike Patton meet, and how did conversations first turn to making music together?

I sent my band PIVIXKI to Ipecac [Recordings, Mike Patton and Greg Werckman’s label] to consider for release, alongside some other music I’d done, which included my second Tzadik album Chromatophore. When Mike was in Australia next, he called me for a coffee and I went to see him, and he immediately told me he wanted to do something together. So it was really like that, very simple. Mike told me later that the Tzadik record really spoke to him as a composer, and convinced him that I was someone he could work with. How that was going to take shape took about 4 years to figure out.

In the meantime PIVIXKI and Mike did a trio show together in San Francisco, which went really well. It was solid gold. I mean, Max and I were playing all the time at that point, and we both loved San Francisco. The gig was packed, Mike slid into the music very naturally because I think the music really resonated with him and he was obsessively listening to our album. It’s pretty hard to have a bad time playing crazy piano-grind music to a packed venue.

Then I moved to Europe, PIVIXKI went on hiatus and I started to focus on tētēma stuff alongside the Thymolphthalein quintet and my compositional work. The groundwork or kernels for [tētēma’s debut LP]

Geocidal were eventually conceived in complete isolation in a rural French town, where I generated about 27 ideas to present to our drummer Will Guthrie. Will and I recorded all of these on drums and prepared piano in Paris, so the first record really started with that. I then started overdubbing all of the synths and orchestrations in different parts of the world. It’s always a very organic process of layering with tētēma, little idiosyncrasies spawn other ones.

With PIVIXKI in 2011, Photo: Sabina Maselli

How aware were you then of each other’s work? Were you a fan of his beforehand? Was he a fan of yours?

I think Mike may’ve heard about me first through [frequent collaborator] John Zorn, then later again through [Patton’s Mr. Bungle bandmate] Trevor Dunn. Zorn signed me to Tzadik when I was 24, which was the result of Oren Ambarchi encouraging me to send my early percussion music to John. So again, just sending things in the mail!

In Melbourne and Sydney at the time, there was quite a healthy bleed between contemporary notated music, Downtown NYC influences, Australian experimentalism and Japanese noise/underground currents, largely due to the What is Music? Festival. I grew up musically in the thick of that. That was also when I first heard all the Mego stuff live: Pita, Hecker, Farmer’s Manual, Fuckhead, Fennesz; all of those people came to Oz thanks to Robbie Avenaim and Oren, and peripherally Mark Harwood. It was a pretty amazing time to be a young musician into weird stuff… I mean at one gig Robin Fox and I were opening for Voicecrack and Otomo Yoshihide at the Sydney Opera House studio and it was packed!

Patton and other members of Bungle played earlier versions/events of the festival in the mid 90s, I think, doing Zorn’s [1984 composition] Cobra as well as their own, more conceptual offshoots like Nottingturd Fan, at a place called the Harbourside Brasserie in Sydney. This is how I think Trey Spruance ended up on a Machine For Making Sense album, for example. So there was somehow a loose connection between what those US avant guys were doing, and what was happening in Melbourne and Sydney.

Trevor and I met on July 4, 2006, at a weird rooftop party in Midtown, New York. I was living in Berlin at the time, and had come to NYC to play some shows at Tonic and The Stone. The Tonic show was my first collaboration with Anthony Burr, a fantastic Australian clarinettist who has lived in the states since the early 90s. It must’ve been good because the only two guys at the gig made out the whole time, then thanked us for the music afterwards.

I was supposed to do the show with Dion Workman, someone who I liked very much and respected musically through his solo work and with Thela, but he had recently quit music and was on a martial arts retreat in Colorado. His girlfriend was very welcoming and let me stay at their apartment while Dion was away, and she invited me to some July 4th party to meet other people. This party is where I met Trevor, and we hit it off immediately, principally talking about how weird it is to write compositions for your own instrument then get other people to play it (he had had a bad performance of a double bass piece). We’ve remained friends ever since.

So to answer your question, it was interesting to meet Trevor because as a teenager I listened to Bungle a lot, and Trevor was really key in the founding of that group. To me, as someone studying classical piano while listening to whatever metal my older brother and his friends were into, Bungle was one of the only bands that made sense of those aesthetic poles. After Bungle, I kinda dropped out of what Mike was doing.

How often do the two of you see or speak to each other now?

When we’re making albums, we drive each other crazy with endless daily emails and texts about the music, then suddenly, when it’s done, it all stops. It’s a very intense process, and even though English is both our native tongues, this does not guarantee that American and Australian sensibilities communicate easily! So there’s that too, making oneself clear sonically while navigating the other person’s life and mood across time-zones and constantly fluid circumstances, which, I can assure you, goes both ways. Other than that, Mike and I average actual contact once every couple of years, and it’s usually when I open for one of his bands.

Can you take me through the specifics of how the two of you work together?

I start it off by making a skeleton of the album which comes of out raw materials. For the first album it was with drums and piano in Paris like I said, for the second it was a group of samples collaged over amplified prepared piano. Broadly speaking, this takes about 2 years of composing, mixing and arrangement, then I’ll send it to Mike when I feel it’s ready. He’ll then sit on it for about a year. In this period, I’ve no idea what he’s doing, but I assume he’s absorbing the music and composing ideas for it.

At some point, he’ll do a rough pass of the whole album, which is often lyric-less vocalise, some words here and there, some flickers of melody, some harmonies; fragments of what will eventually be the final arrangement. I give him feedback on that, put more overdubs on, but the arrangements and forms don’t change from there.

Selfie, 2020

At this point, I mix everything, including the rough vocal, to a point where I feel like it’s basically done. Also at this stage, I do what we’ve come to refer to as a lyrical “translation”: I listen to Mike’s vocal abstractions, and write words which fit the rhythms and curves of what he’s singing. As you can imagine, this does not always work, as it’s me putting words to his vocal ideas, which above all, have to feel natural to him. However, most of the time it does, the success of which stems from his trust in me, my willingness to work with and listen to his acute instincts as a vocalist.

After all this, I give it all back to Mike, as finished as possible, with lyrics and wait another year. Then, out of the blue, with no warning, I’ll start getting final vocal takes in my email. Like a lot, each day. These usually come with a list of questions “does this work? i changed this word, ok? I did this because…what do you think of..?” etc. This process this time around, took 2-3 months of solid back and forth between La Becque in Switzerland and San Francisco.

Eventually, 13 songs later, we had a record. When we finished it, it really had the feeling like the dust settled and suddenly there was this glowing, powerful thing.

When did work start on the new tētēma album, and how quickly/slowly did work progress?

I started the beginning of 2015 with the prepared piano recordings at Ausland in Berlin, just after Geocidal came out. I somehow felt I hadn’t really said all I wanted to say with this project, which is usually when I stop my bands and projects. I enlisted Roy Carroll to come and help me with this idea of putting prepared piano through bass amplifiers then miking the room, because I wanted to create these harmonically active and percussive grooves with space around them. Eventually, I threw a lot of it out because it sounded immediately too much like Konono No.1, however the stuff that stayed on the album has its own thing. I sat with that for a while, not really knowing what to do with it, then life circumstances drew me back to Australia.

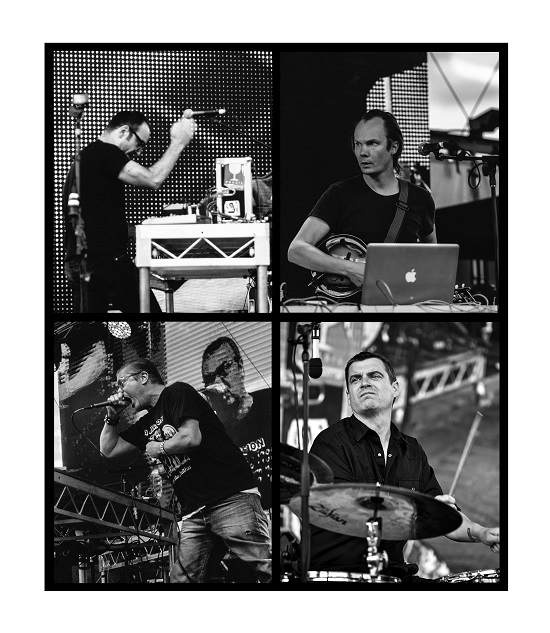

tētēma’s one and only live show. Photo: Aaron Chua

At some point I decided to edit the prepared piano materials in loops and try to synchronize actual tape loops to these digital edits. I put this into practise in Jérôme Noetinger’s basement, while back in Europe on tour at one point when we has still doing Metamkine distribution. I mean, I had the whole catalogue to choose samples from! So it all grew out of that until mid-2017, which is when I sent the first version of the album over to Mike. Like I said, it’s always very organic, and very much a diaristic approach to music reflecting where I’m at on the planet and where I’m at with myself at the time. I should mention that there’s no click tracks, as I try to keep a priority for human feel where possible. At lot of this comes out of how Will played drums to the electronics and vice versa. There’s no main ‘grid’ which everything is timed to.

How can you tell when a project has ‘said all it needs to say’?

I feel that there are two poles you oscillate between as an artist, and they interact differently depending on the person. You can refine one approach forever until it becomes a singular thing, or you try a bunch of experiments with different strategies and see what happens. I very much fall in the second category, in that I try to push particular aesthetic ideas until they collapse.

Usually what happens is that I bring a group of people together who have particular musical idiosyncrasies and talents, and then investigate a specific musical area until possibilities are exhausted. I guess this goal is pretty common, but for me it’s all about trying create something I’ve personally not heard before. Whether people like it or not is secondary, and of course it’s very nice when they do! But the trick for me is to keep pushing and stay slippery, for myself. If a particular project begins to repeat itself aesthetically or technically, I feel it’s time to stop.

Do you think there will ever be another tētēma live show?

Man, no one even knows if there’s going to be any live music for a while at this point! Like all touring musicians, many or all of my shows this year are likely to be cancelled. I’m not sure Faith No More will be playing their planned stadium gigs anytime soon, let alone Mike doing tētēma stuff!

tētēma’s new album Necroscape is out now via Ipecac Recordings