Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

The gaps between musical genres are painted in fuzzy shades rather than smart geometrical lines, making it nigh-on impossible to tell where one ends and another begins. This, on the whole, is a good thing. But it means the true pioneers can sometimes fall between the gaps. So Solid Crew, a collective of MCs and producers from South London, arguably fell victim to this fate: too early for the grime explosion and too late for UK Garage, their place in history is uncertain, even as grime bursts with millennial health.

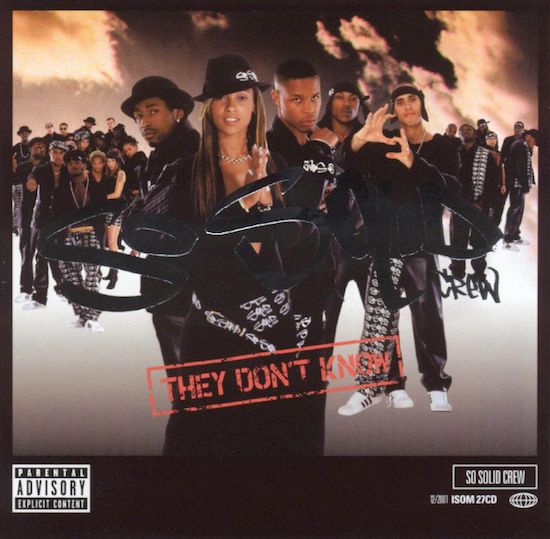

What, exactly, were So Solid Crew? Ask three British people and you will get three different answers. Ask three Americans and they won’t have heard of them. But So Solid Crew – and in particular their 2001 debut album They Don’t Know – are impossibly important for British music. So Solid were grime pioneers and huge pop stars, the last genuinely feared mainstream pop phenomenon, a group of superstar MCs who owed little to US hip hop stars and didn’t really care what they thought, anyway.

Going back further, you can compare So Solid Crew to the Sex Pistols – a cliché, maybe, but one that rings true for once. So Solid, like the Sex Pistols before them, weren’t just a musical phenomenon, they were a cultural sensation, too, a combination of musical anarchy and utter cultural disruption that changed the British musical map forever. Listen to So Solid Crew and you can hear the world bend around you.

And So Solid Crew were hated for it: their music’s brutal energy was an insult to the UK Garage community; their supposed lawlessness a red flag to police. Like The Sex Pistols before them, So Solid were stopped from performing around the UK – a December 2001 tour was cancelled after a shooting at MC Romeo’s birthday party at the London Astoria – and vilified by press and politicians alike. A spokesperson for the University Of East Anglia Students Union, where their tour had been due to start, told the NME at the time that the police had told them they would have to lay on extra officers for the So Solid gig “and someone would have to pay for them. I can never remember any event here when that has happened in recent times. The only time I believe it had happened in the past was on the Sex Pistols tour.”

"We were getting compared to people like the Sex Pistols,” producer Mr Shabz told The Guardian in 2005. “Now black music in this country is getting bigger. The problem was, we were the only ones up there at that time. The government didn’t like it. We were made scapegoats. We were in south London but if something happened in Birmingham, it would be because of us.”

Shabz was referring to an incident in January 2003 when two Birmingham teenagers were shot in the crossfire between rival gangs, which led then culture minister Kim Howells to decry “idiots like the So Solid Crew glorifying gun culture and violence,” while Home Secretary David Blunkett called their lyrics “appalling.” Bizarrely, So Solid would also get it in the neck from the garage committee, a group of prominent UK Garage DJs who believed that the darker sound of So Solid would attract undesirable elements to the clubs.

Musically you can make a case for So Solid being both more important and more original than the Sex Pistols. What the Sex Pistols did with their guitars was far from new, borrowing from The Ramones, the Stooges, the New York Dolls and even the UK’s pub rockers. ‘Anarchy In The UK’ was a fantastic record that crackled with venom. But its innovations came in lyrics and attitude, which were paired to a fairly traditional rock & roll attack. So Solid Crew’s ‘Dilemma’, however, sounded like little else on its release in 2000, its bare-bones rush little more than spartan drum hits and a mutating bass line. As a precursor to the minimal filth of Youngstar’s ‘Pulse X’, ‘Dilemma’ helped turn on a generation of British Playstation producers, for whom UK Garage was too ornamental; too old.

So Solid weren’t entirely alone of course – musical pioneers rarely are – with Pay As U Go releasing ‘Know We’ in 2000, while then Pay As U Go member Wiley apparently produced (but didn’t release) ‘Eskimo’ in December 1999. We shouldn’t forget the work of loveable UK Garage MC group Heartless Crew, another grime precursor, or So Solid production duo Oxide & Neutrino, who topped the UK charts in May 2000 with ‘Bound 4 Da Reload (Casualty)’, either. But none of these would have as great an impact as So Solid, who topped the UK album charts just a year after their debut single.

The other remarkable thing about ‘Dilemma’ was that it came backed by another hugely important tune in the evolution of British music: ‘Oh No (Sentimental Things)’. While ‘Dilemma’ was moody, ‘Oh No’ distilled the group’s South London energy into a wonderfully unlikely pop song, all acute angles, bass rumble and MC braggadocio, as So Solid traded verses over a beat that seemed equidistant between Timbaland’s R&B experiments as by UK Garage’s two stepping lurch. Even more remarkably, the song has a brilliant singalong chorus, courtesy of Lisa Maffia, the kind of feel-good hook you could sing in the shower without ruining your garage credentials, lifting the song into genuinely anthemic status. Wiley, in a rare attack of modesty, would later call ‘Oh No’ the record that started grime but the lines between genres were still so fluid at this point that ‘Oh No’ featured on numerous garage compilations in 2000, alongside the noticeably more fluffy Dreem Teem and Artful Dodger.

So Solid Crew’s towering ambition would become gloriously evident on ’21 Seconds’, which followed in August 2001. The song’s brilliance was in its simplicity – So Solid members were given 21 seconds to perform a verse over a rinkadink garage backing, with the spirit of competition birthing a riot of energy and panache. It’s the kind of idea that sounds glaringly obvious after someone has done it and would later set the blueprint for MC-packed crew grime records like More Fire Crew’s ‘Pow!’ Complaining that the ’21 Seconds’ instrumental is a little perfunctory misses the point of where the real action is as ten of So Solid’s MCs tear through the song like a pack of wild dogs.

American listeners to ’21 Seconds’ might consider lyrics like “Every lyric I do / Every lyric I say / Every lyric I rock / Every lyric I play / Every lyric I make / Every lyric I break” and wonder what the hell the fuss was about. But this, perhaps, was partly the point. So Solid were part of a new generation of British MCs who didn’t necessarily look to Americans for approbation. Rather, they came though the Jamaican tradition of the dancehall deejay, which filtered through to jungle and UK Garage, whose MCs were genuine masters of ceremonies, their primary aim to get the crowd moving in clubs and on pirate radio.

So Solid may have been fans of US rap. But they had their roots in the UK’s traditions of sound systems, pirate radio, jungle and garage rather than the freestyles and mixtapes of the US. The group started when Megaman and G-Man met at pirate radio station Supreme FM in early 1998, going on to host So Solid Sundays on Delight FM until success intervened. So Solid’s lyrics were more complex than the hype fare of the typical club MC. But the energy – and, yes, repetition – at the core of their performances shared a distinct DNA with the ceaseless hype these occasions demanded. ’21 Seconds’ was a rare song that managed to capture the excitement of clubs and pirate radio, with MCs frantically passing the mic as they try to outdo each other in lyrical prowess, creative aggression bubbling beneath the surface.

There was, of course, British rap before So Solid, often brilliant and distinctive in its own right. London Posse released Gangster Chronicle in 1990, which nailed a genuinely British rap style. But British rap always felt a little crippled by its genre, as if sharing a language with the genre’s American pioneers made it feel inferior by default. The emergence of UKG, So Solid and grime allowed British MCs to swerve this comparison by putting their name to new styles. Suddenly British MCs weren’t followers in American music; they were leaders in their own thing, sitting proudly on the frontline of a new phenomenon rather than trailing on someone else’s coat tails.

But So Solid Crew weren’t satisfied with just reputation. While UK rap could occasionally sound rather apologetic in its demands, So Solid made British MC culture sound big, ballsy and extremely pleased with itself. Rarely was this so true as in the iconic video for ’21 Seconds’, a big-budget, FX-laden phenomenon, whose cinema premiere proved So Solid weren’t messing around. “I felt if we were going to make the world look at the UK street culture in music differently, forever, we’ll need to come movie-like and present something visually, that the music world would highly respect,” Megaman told Udiscovermusic in March 2020.

’21 Seconds’ was a massive UK hit, shifting 118,000 copies in its first week on the way to the number one slot. It was inescapable in the summer of 2001, a juggernaut of a song that blasted from car radios and dominated music TV. It was a paradigm shift for British music: here was a London rap song bigger than anything the Americans were serving, a number one smash that hit hard – the sound of clubs clinging to the top of the charts, undiluted.

So Solid made hay. “We were the first UK garage crew to go to No 1,” Megaman told The Guardian in 2017. “The label was supporting members who weren’t signed to them – paying for cars, food and clothing. Sometimes the label said they weren’t going to pay for something, but I was like: ‘You are, or I’m not leaving my house.’ I was looking at the Puff Daddys and rappers of the world who were doing million-dollar videos, and I didn’t want to be any less cheesy than them."

The group’s debut album, They Don’t Know, followed in November 2001. By the time it came out, half the country idolised them, while the other half was praying for them to fail. Already, the group was suffering in the public eye for a mixture of things that weren’t their fault – the shooting at the London Astoria – and things that definitely were, with MC Skat D convicted in October of breaking a 15-year-old fan’s jaw.

You might think that by this point So Solid had nothing to prove to anyone, having scored a runaway number one hit. But the music industry, then more than now, was dominated by albums, which made more money and indicated lasting success. One-off hits from the British musical underground were occasional flashes of lightning – in June 2001, DJ Pied Piper and the Masters of Ceremonies hit number one with their pop garage number ‘Do You Really Like It?’ – but hit albums were far rarer. Drum & bass has only spawned a handful of hit artist albums; UK Garage almost none. The pressure, as So Solid later acknowledged, was enormous, but the album that came was a flawed classic of British music.

If anything, it felt like So Solid were suffering from too many ideas on They Don’t Know rather than bending under creative pressure. The album itself stretched to 20 songs, hosting everything from piano balladry (‘Way Back When’) to scorching techno beats (‘Friend of Mine’), the Knight Rider theme tune interpolating ‘Ride Wid Us’ and what sounded like bleep & bass breakbeat (‘Woah’). Individual songs were packed with often incongruous detail: ‘Deeper’, a personal favourite, combines a two-step beat, topical foot-and-mouth references, a primal bass thump, synthesised string lines, Romeo’s ode to his mum, a sensual (if slightly ill-fitting) Lisa Maffia chorus and a brilliant and entirely unexpected beat switch-up three minutes in.

While ‘Dilemma’ (which doesn’t feature on the album) and ’21 Seconds’ (which does) were the sound of one fantastic idea, brilliantly exploited, much of They Don’t Know is thrillingly maximal, the chaotic sound of a group exploding with musical potential and unafraid to make mistakes as they punch a hole in the British musical firmament. The orchestrated chaos of They Don’t Know is all the more exciting when you realise that the group were essentially travelling with no road map. The Streets’ Original Pirate Material was released in March 2002; Dizzee Rascal’s Boy In Da Corner followed in 2003; Wiley’s first album was released in 2004, while Kano’s debut album hit the shelves in 2005. So who were So Solid going to copy back in 2001? They were gloriously out there, alone.

They Don’t Know was a brilliant riposte to anyone who might have thought that topping the singles chart had gone to So Solid’s heads. Sure, the album had hooks, from the nagging vocals on the title track (a song that appears to be composed of about 50% choruses and 45% swagger) to the maddening synth/bass riff call and response on ‘Woah’. But it was as hard as a Bermondsey foundry, oozing with the same sub bass, distorted synth lines and serrated drum hits that had made ‘Dilemma’ such a musical slap in the face. There can be few multi-platinum albums in history that made such a virtue of their crude sonic force.

They Don’t Know was hugely experimental in its production too, with the drums (especially) pointing the way towards grime. UK Garage and its 2-step offshoot might have dabbled initially in experimental drum programming but by 2001 many of the more commercial UKG songs were built on predictable drum patterns. The drums on They Don’t Know – and especially on songs like ‘If It Was Me’ and ‘Deeper’ – were all over the place and fearsomely funky, nodding to dancehall, 2-step, house and hip hop without ever bending a knee to one genre, in a way that Dizzee Rascal would take up on Boy In Da Corner two years later.

Any arguments over whether So Solid laid the foundations for grime – and for various professional reasons I have spent the last two years having precisely this argument – should be immediately settled by listening to the final third of ‘Deeper’, where bass synth stabs rebound off rudely asymmetrical drum hits in a pure display of grime avant la lettre. Other writers, notably, grime historian Dan Hancox, have noted the importance of They Don’t Know on the growth of dubstep, which was just about coalescing into a scene around London club FWD>> in 2001, with the prowling, metallic bass that opens So Solid’s ‘In My Life’ reminiscent of those early Coki or Loefah productions.

The fact that They Don’t Know wasn’t widely acknowledged as an important album at the time of release may have something to do with its chart success, with the album selling 100,000 copies in its first week of release. Musical pioneers, in the public imagination, are meant to suffer underground for their art. We don’t expect them to win Best Video at the champagne and canapé-soaked Brit Awards, as So Solid did in 2002, and this success may have blinded audiences to what a ground-breaking album They Don’t Know really was.

So Solid arguably also suffered for the ground-breaking perfection of their first two singles: ‘Oh No’, ‘Dilemma’ and ’21 Seconds’ were such brilliantly realised examples of pop experimentation that it was perhaps inevitable that the album would initially disappoint. It seems incredible now that So Solid’s reputation muddied the musical gutter, while Original Pirate Material and Boy In Da Corner – two albums that owe considerable debt to the So Solid sound – were lauded to the heavens. Not that the artists themselves were to blame: in a 2002 interview with MTV, Mike Skinner named So Solid Crew as the only other British MCs to pave the way for what he was doing, while Dizzee was caught up in the kind of beef with So Solid that precludes giving them much in the way of heartfelt affection.

Then again, if So Solid’s reputation stumbled after the release of their debut album, much of this was due to So Solid themselves. Like the Sex Pistols two decades before them, So Solid went into very public meltdown in the face of intense pressure from friend and foe alike. In 2002, Asher D (now better known as actor Ashley Walters) was sentenced to 18 months in jail for possessing a firearm; one year later G-Man was found guilty of possession of a loaded handgun, while Megaman and Romeo both faced court cases (Megaman was cleared after a retrial; the prosecution decided not to continue the case against Romeo). “It was a lot of pressure,” Harvey, one of the group’s most prominent MCs, told the Hip Hop Saved My Life podcast in early 2020. “There wasn’t anyone else to share it with. There wasn’t any other rappers by our side. We were in the charts with Robbie Williams and Kylie Minogue. The black boys from Battersea. Also, we got threatened by every gang in Britain.”

Jealousy wasn’t the only way So Solid’s unlikely success got in their way. “After the success of ’21 Seconds’, the labels were piling in to sign me,” Lisa Maffia explained in 2017. “I didn’t understand at the time, I thought, ‘Why would they want to sign me? I haven’t even proposed enough material for them to sign someone like me’. Now I understand, though. I was the only girl, I was very commercial. It made sense for them to snap me up, it was the next move for So Solid Crew. They gave me an offer I couldn’t refuse. £350k. I just couldn’t turn that down.”

The music industry’s burning desire for quick cash meant that a series of underwhelming solo albums followed, right when So Solid should perhaps have been concentrating on making their second album. Romeo’s 2002 solo album Solid Love sold just 40,000 copies, while Lisa Maffia’s First Lady peaked at number 44 in the UK charts, despite being home to the wondrous hit single ‘All Over’. What should have been a Wu-Tang style takeover ended up being a serious dilution of the brand. When So Solid’s second album, 2nd verse, dropped in September 2003, with a style that jettisoned the experimental filth that made the group so special in favour of a slicker, more US sound, it could only limp to number 70 in the UK charts. So Solid sputtered to a halt in a trail of reality TV appearances, failed solo albums and acting careers.

So Solid weren’t finished: the group continue gigging and sporadically recording today, even re-recording ’21 Seconds’ in 2019 with D Double E, Ms Banks, Toddla T and DJ Q. But it is their influence that really lives on. Success, of course, has many fathers but could grime really have taken life without So Solid making the leap from UK Garage to minimal electronics on ‘Dilemma’? Would a generation of British MCs have felt the confidence to move from radio and club spitting to 12 inches without seeing So Solid blasting out their London rhymes on prime-time TV? Would Mike Skinner or Dizzee Rascal have felt confident developing their idiosyncratic tracks into gloriously uncompromising albums without They Don’t Know dropping in its 20-track glory? And without all of that, would people really give a shit about UK MCs, from Stormzy to Bugzy, in 2020? I doubt it.

"All the risks that we took, all the court cases, all the mad things that you’ve seen, the negativity that followed So Solid, as well as the positivity, it was all worth it now when I see that we have an industry that is on par now with America,” Harvey said on Hip Hop Saved My Life. “If anything, people are more interested in our country now than the Americans.” 20 years ago that would have sounded preposterous. That it doesn’t in 2020 is tribute to So Solid in their wonderful, anarchic, experimental and occasionally self-defeating glory.

Listen to the Line Noise podcast on So Solid Crew and grime here