More than most musical traditions, jazz has been hit particularly hard by the ongoing Corona virus crisis. There are the obvious fatalities caused by the virus: reedists Lee Konitz and Giuseppe Logan, trumpeter Wallace Roney, bassist Henry Grimes, pianist Ellis Marsalis, and producer Hal Willner, among others.

But the music itself has always fed upon intense social interaction. At once a cliché and a deep truth, jazz performance relies on the feedback and energy of an audience—to say nothing of the charged interplay between band members—and that crucial element of the music has been silenced over the last couple of months, and it certainly looks to continue that way long into the future.

No amount of streaming solo performances can make up for the chemistry and energy of either an assured working band or the go-for-broke excitement of an ad-hoc encounter between disparate musicians.

The following ten albums are terrific, and were made well before our new reality descended. I’m sure lots of worthwhile albums are on the near horizon, too, but if any musical tradition can weather these difficult times and devise a new way to move forward, I’d put my money on jazz and improvised music, which has a century of experience adapting, mutating, and surviving.

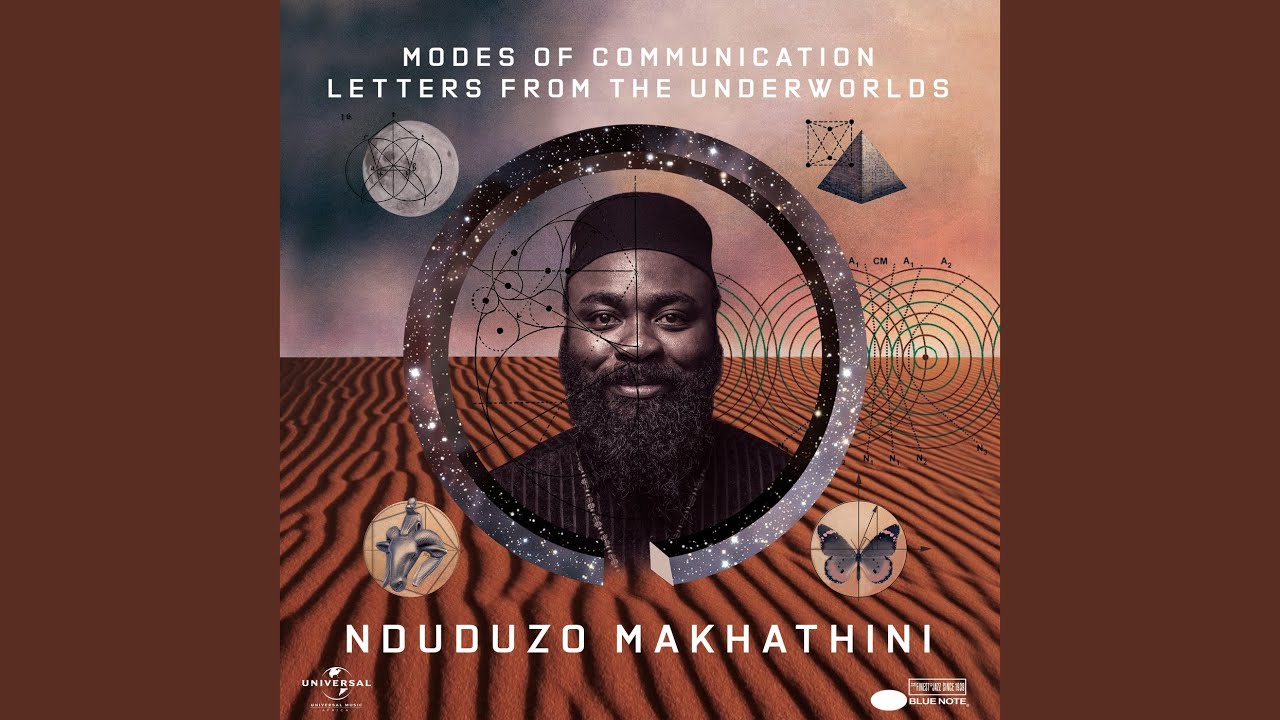

Nduduzo Makhathini – Modes Of Communication: Letters From The Underworlds

(Blue Note)

Nduduzo Makhathini has become a serious force in South African jazz over the last decade, absorbing lessons from the late pianist Bheki Mseleku before immersing himself in the globalist aesthetic of Randy Weston and spiritual jazz of John Coltrane. The sound of Trane’s long-time pianist McCoy Tyner looms large on Modes Of Communication: Letters From The Underworlds, Makhathini’s eighth album, but there’s no question he’s forged is own vision, toggling between Ellingtonian balladry (‘On the Other Side’), vintage South African gospel (‘Saziwa Nguwe’), and searing modal excursions that veer toward ritual. His terrific core band is enhanced by the presence of versatile, fiery American saxophonist Logan Richardson, who blends in easily and reinforces a Transatlantic continuum, while the leader’s wife Omagugu Makhathini is one of several singers that expand the music’s reach beyond post-bop. The impressive range of the album from tune to tune always feels cohesive and holistic, even when the ghost of Coltrane dominates as on ‘Isithunywa’ or on the album’s nominal centerpiece ‘Umlotha’, a poignantly lyric meditation that deftly opens into an eloquent three-way free jazz exchange between Richardson, tenor saxophonist Linda Sikhakhane, and trumpeter Nadabo Zulu without ever surrendering its graceful foundation.

Irreversible Entanglements – Who Sent You?

(International Anthem/Don Giovani)

In the last few years the fury and indignation of Moor Mother (aka Camae Ayewa) has maintained a steady keel, fuelled by an endless barrage of injustice and inequality. But she has widened her scope, deploying metaphors, images, and straight talk that allow her to speak more broadly about the fucked-up state of the planet without abandoning her disarming observational acumen. She sounds less enraged on the superb second album by Irreversible Entanglements, but she’s never seemed more locked in, masterfully manipulating cadence, silence, and a sense of indignation. The instrumentalists in this agile quintet—bassist Luke Stewart, saxophonist Keir Neuringer, drummer Tcheser Holmes, and trumpeter Achiles Navarro—have further focused a simmering intensity. While Neuringer and Navarro each composed one of the five pieces, the rest are collective improvisations that hold together thanks to a deftly refined, almost conversational interactivity; whether written or not, the band leans into the music as one, improvising heavily without every losing the driving rhythmic thrust. On ‘The Code/Amina’ Ayewa quotes Julius Eastman, intoning “stay on it”, before wondering where our collective breaking point is: “When do we go off script? / When do we step out of a daze, dumbfounded and dazed / Return back to humanity.” While the parallels between this band and Amiri Baraka’s work with the New York Art Quartet remain firm, there’s nothing antiquated or retro about this album. It’s as relevant, timely, and electric as anything I’ve heard this year, but it’s the sense of urgency that’s kept me riveted.

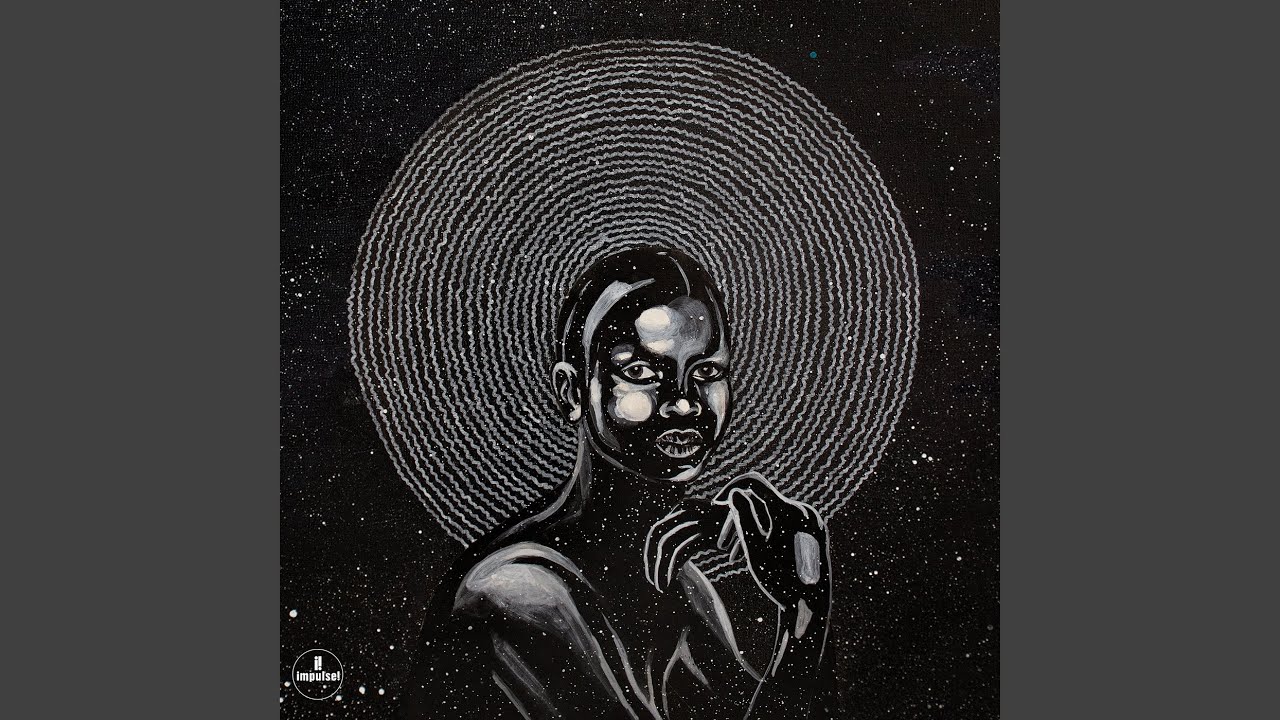

Shabaka & the Ancestors – We Are Sent Here by History?

(Impulse)

Reedist Shabaka Hutchings uses the bracing second album by his South African band the Ancestors to forge an alternate history of Africa and its diaspora, taking the reins of the narrative to build a kind of Afrofuturist analog. As he told Damien Cummings in a recent feature for this site: “It’s that play between what has happened and what will happen – the present being the pendulum swinging in between.” The music feels more propulsive and focused than the material on the group’s impressive 2016 debut Wisdom Of The Elders, and while the brisk opener ‘They Who Must Die’ refers back to the message from that record, as doomsday descends, the rest of the recording tries to envision a more spiritual and equitable future in the midst of brutality, toxic masculinity, slavery, and oppression experienced for centuries. Helmed by the muscular bass lines of Ariel Zamonsky—who seamlessly twines melody and groove—and frequently driven by the hectoring chants and soulful singing of Siyabonga Mthembu (who co-wrote the lyrics with the leader), the band spaciously balances skittering Caribbean grooves, springy post-bop, and exploratory improvisation. There’s a dark fury in the attack, but there are also moments of yearning repose, such as the meditative conclusion of ‘You’ve Been Called’. Ensemble interplay dominates—especially between Hutchings and fellow reedist Mthunzi Mvubu—with a freedom untethered from any single tradition.

Kaja Draksler Octet – Out for Stars

(Clean Feed)

The Slovenian pianist Kaja Draksler has established her brilliance as an improviser in various contexts, whether a duo with Portuguese trumpeter Susanna Santos Silva or her cubist trio Punkt.Vrt.Plastik with drummer Christian Lillinger and bassist Petter Eldh, she’s turned to this plangent chamber octet to explore her interest in composition, although, naturally, her ensemble brings a serious improvisational rigour to the performances. The group’s stunning second album features original settings for the poetry of Robert Frost, sung in varied styles by Laura Polence and Björk Níelsdóttir, while her instrumentalists articulate her melodies and structures with gauzy finesse. There’s a meditative downward motion played by violist George Dumitriu and bassist Lennart Heyndels on ‘Danas, Jučer, Sutra’ (on the poem ‘A Passing Glimpse’), embroidered by improvised commentary from reedists Ada Rave and Ab Baars, as the vocalists deliver folksy unison lines, while a piece like ‘Acquainted With The Night’ opts for a more open setting, including trenchant, twitchy interplay between the pianist, the bassist, and drummer Onno Govaert, as the singers quietly chant the poetry, as much as a sonic object as a subdued melody. The singers are more animated and chattery on the loping ‘The Last Mowing’, with raucous accompaniment by the squawky reedists, while ‘The Silken Tent’ enlists the vocalists in more operatic fashion, and Draksler even interpolates some Handel. Each piece offers a different perspective for Frost’s language, matching a sonic landscape to complement his evocations of nature.

Liberty Ellman – Last Dessert

(Pi)

Guitarist Liberty Ellman is a musician of great thoughtfulness. Despite his versatility and depth, he’s judicious about recordings, and Last Desert is his first album as a leader in five years. Although he’s worked in recent years with saxophonist JD Allen, bassist Stephan Crump, and pianist Myra Melford, he remains known best for his integral work with composer and reedist Henry Threadgill, particularly in the quintet Zooid. Here he leads a phenomenal sextet—with fellow Zooid member Jose Davila on tuba—that adroitly articulates his sophisticated arrangements, deploying sensitive ensemble interplay. The opening ballad ‘The Sip’ is a chamber-like marvel proceeding at a slinking tempo that underlines the gorgeous array of multilinear exposition from the leader, alto saxophonist Steve Lehman, and trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson. The episodic two-part title piece, where a Threadgill influence surfaces, embraces a dynamically shifting landscape, moving seamlessly between stasis, groove, and controlled chaos, but Ellman’s elaborate compositional design never thwarts the freedom afforded to each player, where individual soloists are consistently prodded with spontaneous interjections or contrapuntal charts. The tightly coiled ‘Doppler’ uses subtle hocketing techniques and the stuttered beats of drummer Damion Reid provides an exacting tension to the pointillistic array of notes produced by the rest of the band. Ellman prefers a clean guitar tone, and, in general, the music occupies a measured energy—but for all of its subtlety, the music is packed with ideas that are a joy to parse.

Alexander Hawkins & Tomeka Reid – Shards & Constellations

(Intakt)

The first recorded collaboration between British polymath pianist Alexander Hawkins and the versatile American cellist Tomeka Reid reveals a natural rapport that takes multiple shapes. Eight of the recording’s ten tracks are free improvisations, most of them focusing on refined dialogues rife with extended techniques, subtle textural shifts and quicksilver responses. The opener ‘If Becomes Is’ finds Reid initially producing brittle, wandering pizz figures that gradually morph into an elusive rhythmic thrum in sync with Hawkins’ patient organisation of pointillistic notes into fitful, cycling patterns. The pianist summons the sound of early free jazz piano on ‘Danced Together’, with a jagged left hand chordal runs intersected by the cellist’s toggle of clean walking lines and dissonant, plucked note clusters. The duo seems to be of a single mind, together finding a pathway, whether abstract or linear, regardless of how far apart them might appear at the beginning of each piece, but that connection never opts for the glib or predictable. They also imaginatively essay a couple of tunes from the AACM songbook.—the lyrically yearning ‘Peace On You’ by Muhal Richard Abrams and the elegantly pastoral ‘Albert Ayler (His Life Was Too Short)’ by Leroy Jenkins—a repertoire of great importance for both musicians.

Viktor Skokic Sextett – Basement Music

(Jazzland)

Bassist Victor Skokic has been active in Stockholm’s jazz scene for years, working behind singer Sarah Reidel and playing in the trio the Ordinary Square among other less steady configurations, but at 37 he’s finally dropped his first recording as a bandleader. He’s clearly applied his experience and a surfeit of ideas to the material on Basement Music, an assured debut rooted in post-bop, but informed by a variety of disparate influences. The bassist himself has cited French composer Olivier Messiaen, Swedish jazz-folk pioneer Jan Johanssen, and metal stalwarts Meshuggah as inspirations, although none of those artists can be heard explicitly the sound he’s crafted here. He leads a superb group featuring some of Sweden’s most seasoned players, including reedist Alberto Pinton, trumpeter Emil Strandberg, and drummer Christopher Cantillo. Broadly, the music reminds of the way the excellent Scandinavian quintet Atomic has applied the advanced, multipartite compositions of pianist Håvard Wiik and reedist Fredrik Ljungvkist, where the pull of 20th century classic music looms heavily, to post-bop conventions. As a composer Skokic has a thing for wending melodies and episodic sequences that frequently reorder the action, regularly shifting moods, grooves, and timbre. The fluid implementation of this tactic relies on the improvisational strengths of his band, whose members tend to accent or dialogue with the other voices as each piece unfolds. The group’s rigorous versatility in navigating such turns is never clearer than on ‘Ett Två Tre’, which corkscrews between jagged swing contours, a garrulous, lurching clarinet solo by Pinton, and an extended passage of minimalist bass clarinet, piano, and bass, before restating the twisting theme.

Tim Berne & Nasheet Waits – The Coandă Effect

(Relative Pitch)

Tim Berne long ago established himself as one of the most meticulous, feverish reedists in improvised music, and by and large he’s devoted his practice to leading bands navigating his labyrinthine compositional style. His writing favours dense, knotty patterns rife with interlocking parts, larding his tunes with a barrage of information that can often leave the listener exhausted as much as exhilarated. So this duo recording with the marvellous drummer Nasheet Waits—known best for his close partnership in Jason Moran and the Bandwagon—offers something different, with a platform unbound by notes on a page. Berne’s tart alto saxophone playing retains a propulsive logic, his lines unspooling with masterly motific elaboration that ponders and deconstructs each phrase from multiple perspectives, while pushed and cajoled by the imaginative, ever-shifting rhythmic landscape forged by his partner. Despite Berne’s craggy power, this is a genuine collaboration that’s less about give-and-take and more focused on achieving balance and mutual energy over a long haul. The bulk of the album is occupied by the 39 minutes of ‘Tensile’, an apt title for the malleable interplay on display, especially during the back half where things chill out, yet the vitality never flags. ‘5see’ is a nine-minute encore from the same concert that seamlessly picks up where the duo had left off.

Anna Högberg Attack! – Lena

(Omlott)

Swedish alto saxophonist Anna Högberg knocked me out with the ferocious 2016 debut of her sextet Attack!, balancing the heat of free jazz with a strong yet unobtrusive compositional underpinning. It’s been a long wait for the follow-up, and happily, Lena delivers in a big way. The leader’s writing draws upon Swedish folk themes (‘Pappa Kom Hem’), modal jazz (‘Dansa Margit’), and contemporary music (‘Pärlemor’, colliding excellent prepared piano work with post-cool horns), yet there’s an attractive transparency at work so that her powerful band—tenor saxophonist Elin Forkelid, trumpeter Niklas Barnö, pianist Lisa Ullén, bassist Elsa Bergman, and drummer Anna Lund—is free to push and pull against the notes on the page. That practice generates an extraordinary tension, but the procedures aren’t nearly as chaotic as that might suggest. Rather, the band knows itself and the material so innately that members are free to go far outside the lines, yet they can snap back into place at the drop of a hat, bringing the focus back to her indelible themes. I’m still eager to see this band live for the first time, but now, as we only have our records, Lena is making me feel more alive than just about anything else.

Gard Nilssen’s Supersonic Orchestra – If You Listen Carefully The Music Is Yours

(Odin)

Drummer Gard Nilssen has been a prolific fixture on Norway’s jazz scene for nearly two decades, working in groups that have toggled in rock fusion like Puma and Bushman’s Revenge as well as combos trafficking in fiery freebop like Cortex and his own trio Acoustic Unity. As part of a residency at the 2019 Molde International Jazz Festival he assembled the Supersonic Orchestra, drawing upon sixteen close collaborators and colleagues to produce an unholy din without eschewing his deep engagement with classic big band verities. Working closely with reedist André Roligheten (Acoustic Unity, Friends & Neighbors, Albatrosh) he co-wrote new pieces and revamped some trio tunes for a saxophone-loaded combo that also featured two additional drummers and three bassists. While the sonic power of a big band is undeniable, in free music the format can sometimes produce overkill, with little space. Nilssen and Roligheten avoid that issue with their dynamic arrangements and compositions that bristle with ebullient melodies, giving the blowouts a sense of joy and vitality rather than relentless weight. On the charged medley ‘Bøtteknott/Elastic Circle’ concise solo strands, punchy contrapuntal riffing, spirited interplay, and downhill velocity produce something bursting with life, at times recalling the verve of Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath. An Afrobeat flavour surfaces in the climactic ‘Bytta Bort Kua Fikk Fela Igjen’, injecting terse rhythmic accents into the shape-shifting epic.