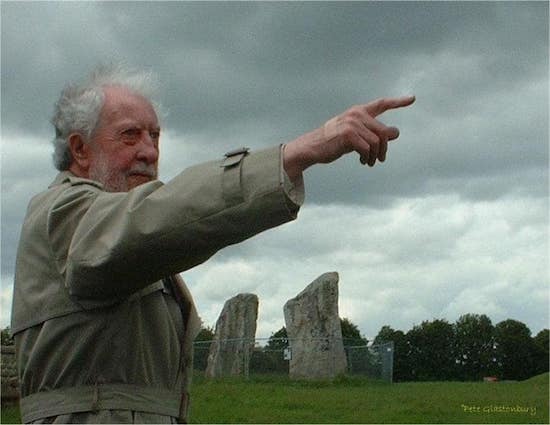

Aubrey Burl portrait by kind permission of Pete Glastonbury

On Wednesday 8 April 2020, Harry Aubrey Woodruff Burl FSA, HonFSA Scot, known to most as Aubrey Burl, died aged 93 in the care home where he had lived for a number of years.

Burl was a boundlessly energetic and prolific explorer, analyst and chronicler of the Neolithic and Bronze-Age sacred monuments of these Islands and Northern France. Between 1976 and his death, he authored at least 23 books and perhaps hundreds of articles on the subject.

His intellectual breadth and vigour also saw him publish a further six tomes on wider topics, all after the age of 70 (spanning from Roman poetry to Welsh pirates; French heretics to – in his 2015 final full-length work – the identity of Shakespeare’s mistress).

Described by the New York Times as "the leading authority on British stone circles", Burl’s books on these ancient sites are near-ubiquitous. They are to be found in libraries of all sizes, from volunteer-run village collections to our great universities; in bookshops of every stripe (academic; travel; local interest; incense and crystals; car boot sales); on the shelves of cloistered dons, on coffee-tables and in ramblers’ backpacks and back-pockets.

However, Burl’s departure passed with curiously scant attention; not publicly known until a week later, there have been no specialist news articles nor obituaries as of yet, 14 days on (though of course a grim backlog from the rolling impact of Covid19 provides a partial reason for this).

Instead, there have been a fairly compact handful of tributes online – as much from musicians and artists as from prehistorians – across message boards and social media. A touching and oddly nostalgic far-reaching flutter of texts and calls were also exchanged between friends, colleagues and admirers.

Contacted for comment here Andy Burnham, Editor of The Megalithic Portal, commended us to the warm and eloquent reflections of the site’s members – such as the tender concision of ‘Combuijs’ – “I have got only worn-out copies of his books.”

Those keen to delve deeper in remembrance under lockdown were further confronted by a strange absence. Beyond details on the books, there is scant biographical information online; no printed or recorded interviews, nor broadcast clips. Likewise, practically no photos of the stones from his (highly visual) published works, let alone of Burl himself. There are, however, numerous Google tunnels to dedications in sleeve-notes, and essays and blogs on experimental film and visionary art.

How was it that the man who did perhaps more than any other to bring these forgotten stones to clarity in the public consciousness could have so receded from direct view himself? And, how might we chart the enduring celestial trail of his creative influence?

Stone Tape #1: Matthew Shaw with Brian Catling & Shirley Collins

Sunken Nightfall from Matthew Shaw on Vimeo.

“Sunken Nightfall centres on the (stone) circle, the seasons, the turning of the wheel… Brian Catling wrote a poem to this piece which was then spoken by the true voice of the English earth and stone, Shirley Collins. Brian is also a huge fan of Burl’s books and continues to read, explore and quest after reading him for the first time all those years ago.”

FROM CARNAC TO CALLANISH (and everywhere in-between)

Born on 24 September 1926, Burl’s career began with four years in the Royal Navy, followed by a stint teaching Latin at a private school.

According to Neil Mortimer (of the band Urthona, but also the Fortean Times’s former Archaeology Correspondent) in the late 1950s Burl – resolved to make a change – headed for the British Museum to research a possible book on the pirate Bartholomew ‘Black Barty’ Roberts. An enticing rabbit-hole in these primary studies led him to seek the contemporary volumes they held on stone circles… only to find there were none.

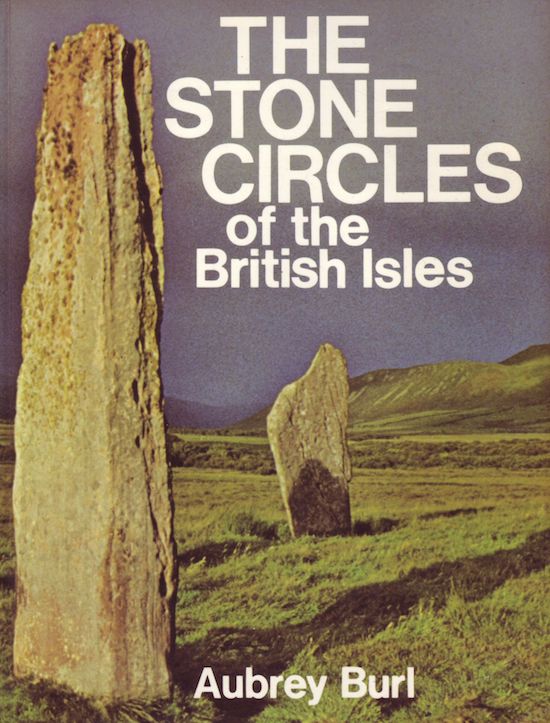

Curiosity deeply piqued by this unexpected gap, by 1966 Burl’s general interest stiffened into an insatiable quest – he would spend the next three years touring Britain’s ancient sites, and a further six writing and conducting targeted fieldwork for what would become his first book, The Stone Circles of the British Isles (Yale University Press, 1976). Seldom out of print but often updated, it has sold over 50,000 copies.

Burl would publish a further eighteen books on the subject in the next 24 years – 3 in 1979 alone – accelerating both academic understanding and public awareness of these sites, and positioning him as a successor to hallowed 17-18th C antiquaries including his near-namesake John Aubrey, ‘druid rector’ William Stukeley and William Borlase.

John Billingsley, Editor of Northern Earth, remembers Burl’s ‘gazeteer books on the UK and Brittany as essential guidebooks’ for archaeologists, ley-line hunters and tourists alike;

Burl insisted on visiting the sites he wrote about, and so was able to build deep understanding of how these monuments connected with their surrounding landscapes. He also firmly believed that only through the in-person study of the circles could one truly begin to grapple with their purpose and the reasons for their construction.

Mortimer recalls with great admiration Burl’s willingness to discuss his ideas – in contrast to some peers who would baulk at the idea of engaging with those ‘outside the academy’. “He once told me, ‘I don’t understand it… I’m quite happy to write for a pagan magazine; I don’t have to agree with everything, I don’t agree with everything – but if they’re interested in what I have to say, and they’re serious and sincere – why should I say no?’”

And yet, Burl’s willingness to accept and espouse the idea that these sites were used for complex spiritually driven rituals, rather than as mere calendars as many ‘scientific’ archaeologists preferred, in some ways placed him in a limbo between the establishment and the earth mysteries community.

This seems unfair given Burl’s abiding focus not on idle fancy, but rather on what Mortimer terms ‘informed speculation’ – rooted in the archaeological record; appreciation of place; and deep historical anthropology, comparing the practices of agrarian cultures across time and continents.

Mark Pilkington (of Strange Attractor Press, and the synth duo Teleplasmiste) frames Burl’s approach beautifully, saying he “always trod carefully, listening to the stones, their histories and those of the landscapes around them, rather than chasing faddish rainbows. He foregrounded the importance of trying to respect and understand the world of the people who built them. ‘Too often the people who built the stone circles have been ignored’ he writes in Prehistoric Avebury (1979), while humanely dismissing contemporary lore about ley lines, earth energies, UFOs etc. as, ultimately, disrespectful: ‘The men and women of prehistoric Britain deserve better than this silliness.’”

Burl’s academic life was also conducted partially beyond the establishment, at Hull College – but as the author, archaeologist and historian Richard Morris (a former commissioner of English Heritage) notes, this “perhaps isn’t a surprise – the adult education/extra mural sector was archaeology’s habitat down to the 1970s, and a lot of very influential practitioners came from that direction.” Burl took early retirement from teaching in 1980, to focus on his writing.

Morris and Mortimer both feel that a more significant factor in Burl’s sometime ‘outsider’ status was his trenchant belief that glaciation carried Stonehenge’s famous ‘bluestones’ to Salisbury Plain from their point of origin in the Preseli Hills of South West Wales. The prevailing view for many others remains that the stones were deliberately quarried and conveyed by the Neolithics themselves, with the purpose of creating the sacred site.

Burl would occasionally do broadcast interviews, but was never inclined to play the game; Mortimer remembers, “They got him on the Today Programme to talk about the bluestones… one of the presenters chirpily asked ‘could ley-lines be anything to do with why Stonehenge is where it is?’ he gave her short shrift: ‘I’m an archaeologist, not a wizard.’”

On the curious absence of print interviews and photographs, Editor of British Archaeology magazine Mike Pitts reflects, “Mainly he was a relatively shy man who did not seek the limelight.”

Mortimer agrees: “Aubrey was an old-school gent. He just wasn’t a self-publicist; it’s something that didn’t turn his bird. I can’t imagine him having a photo-shoot. He phoned me up once – and to my astonishment, asked, ‘Can you meet me at Avebury? I don’t have a single photo of myself there!’ He needed one for Robin Heath’s book on (archaeo-astronomer) Alexander Thom.”

Stone Tape #2: Hawthonn (Layla & Phil Legard)

“Burl’s Rites Of The Gods and Prehistoric Avebury were heavily on my mind when Phil and I visited Avebury in 2011 on our way back up north after playing a gig in Southampton. We went to West Kennett Long Barrow, where we sang vocal improvisations – later surfacing as the opening to Hawthonn’s ‘Lady Of The Flood’.”

THE (PRE-)MODERN ANTIQUARIAN

Aubrey Burl was still publishing prolifically in the 1990s, but a traveller from an altogether different dimension was poised to escort him to the new millennium and a renewed audience.

In the early 1990s, Julian Cope announced he was writing and researching The Modern Antiquarian – his own lavish, lysergic guide to the prehistoric monuments of the British Isles. His enthusiasm for the subject had been previewed through his LPs Peggy Suicide (with photos at the Devil’s Den, near Avebury) and Jehovahkill (the cover featuring Callanish on the Hebridean Isle of Lewis). Still signed to Island at the time, Cope had free reign to emphasise this fascination in his regular interviews.

Interest in prehistory amongst counter-cultural explorers was duly germinated, and further fed by disparate nutrients such as Channel 4’s Time Team (first broadcast in 1994) and the tail end of the rave scene, which produced the new age techno of Eat Static and System 7, and the Megadog club nights.

But The Modern Antiquarian, eight years in orbit, wasn’t to land until 1998; so where could potential henge-heads – activated at this wyrd intersection of archaeological method and psychedelic experience – look for guidance? Raiding the libraries and bookshops, the author who was always to be found on the shelves was Aubrey Burl.

Indeed, timed to perfection, A Guide To The Stone Circles Of Britain, Ireland And Brittany emerged ready to light the path in 1995. Here, simply laid out and easily accessible, was a lifetime of exploration in a concentrated hit. For each site, a location, directions and a description. If you wanted to go, Aubrey Burl would get you there.

Cope pays generous, near-reverential tribute to Burl in his own megalith masterpiece – indeed, the only topic with (slightly) more index references than his 40, is… Avebury, with 43! Stonehenge sits in distant fifth place, with a mere 18 mentions.

As experimental musician, poet, photographer and film-maker Matthew Shaw remembers, “Once Cope’s book had been read and at least a couple of sites visited, the next step was to check out the heads that the Arch Drude recommended. In archaeological terms, Aubrey Burl was the main man.”

Burl repaid Cope’s respect with typical class and enthusiasm, saying of The Modern Antiquarian: “Such a splendid book, splendid in both its illustrations and its prose, rare partners in the archaeological world. I shall use it, of course.” He was far too modest to highlight the echoes of his own practice in this precious combination.

Stone Tape #3: Spaceship

“I made this piece at Coldrum Long Barrow in Kent, formerly mis-classified as a stone circle. It marked a return, for me, to working at megalithic sites and on that beautiful late spring day I was hit by powerful nostalgia for my obsessive Burl-led stone hunting of the mid-90s. The visitors I managed to capture speculating about the site and its relationship to Stonehenge only added to this perfect moment.”

MUSIC OF THE STONES: Derek Jarman / Coil: Journey To Avebury

It seems clear that Cope’s affectionate combination of fealty and patronage for Burl has sustained and further lifted his place in the contemporary creative consciousness, but the roots run far deeper.

“I believe, heretically, that archaeology is not a science, but a branch of the humanities, and that poetry is every bit as important to the prehistorian as physics”, Burl once wrote, neatly encapsulating the convergence of precision and imagination in his work.

Burl’s books themselves are beguiling. His writing is a joy to read – scholarly but un-forbidding; rich with literary allusion, and geographically/temporally transportational prose. As Layla Legard of the band Hawthonn puts it, “When [Burl] describes the first settlers in Wiltshire in terms of ‘when Ur was an important town in Sumer,’ and ‘a time when there were no months or weeks, only day and night and the blurred changing of seasons’ he becomes truly visionary – and we look with him on a vivid panorama of Neolithic life.”

Many ‘serious’ archeology books are visual in that they contain meticulous plans of the sites, and Burl embraces that rigour – but his books are also sumptuously illustrated with full-page renderings of the stones themselves; colossal yet inscrutable, prominent ‘characters’ in their own right (and, indeed, rites). Towards this, Burl had a gift for selecting truly great photographic partners, such as Fay Godwin for Prehistoric Avebury in 1979. Rings Of Stone, his collaboration with Edward Piper, was published in the same year; it rendered explicit a cord of connection to Britain’s Neo-Romantic painters like Paul Nash, Ravilious and Edward’s father John, and their yearning to find answers and relinquish themselves in the shadows of the monoliths.

Like Cope, Coil paid open tribute to Burl in their work – including in the sleeve notes to 1996’s Coil Presents Black Light District: A Thousand Lights In A Darkened Room, which notably contains the tracks ‘Stoned Circular I & II’.

In 1995 – the same year that Burl’s A Guide To The Stone Circles Of Britain, Ireland And Brittany was published – Coil completed a commission to posthumously score the remaster of Derek Jarman’s 1971 short film Journey To Avebury. Taken together, Jarman’s askew pastoralism and the peaceful claustrophobia of Coil’s music provoke the same convergence of solace and unease seen in the work of Nash and his contemporaries.

Little more than ten minutes long, the soundtracked film now seems to exist almost as an artefact of deep pre-Millennial psychic archeology. It beckons the viewer towards further engagement with the source material; to Burl’s work, and with him hand-in-hand onwards down the avenue to the circle.

This is the key, above all. Across five decades, Burl more than anyone has inspired and enabled widespread, direct engagement with the stones themselves. Demystifying whilst re-enchanting. Revealing and emphasising these potent remnants of our ancient past, not as solitary colossi confined to a handful of restricted sites in the South West of England; but an undying communal heritage, diverse and distributed across every region and nation of these islands.

But whatever trip they provide the launchpad for, Aubrey Burl’s life and works fight always to keep the stones at the centre. Here’s Pilkington again, with the final word: “It’s important, rewarding and fun to dream the stones, to engage with their mysteries and respond to their silence: but if you aren’t earthing your imagination in the archaeological record, of not just the sites themselves, but also the complex, interconnected and international world of the circle-builders, then you should be aware that you are creating fiction – perhaps even future myths – but not history. And fictions are good; the stories of the stones are far from over: they, those who study and dream them, Aubrey Burl luminous amongst them, will always be there, flitting about their stillness, shaping the past, the present, and soon, the future.”

Stone Tape 4: Teleplasmiste (Mark Pilkington & Mike York)

“Ancient sites – their presences and resonances – are central to the workings of Teleplasmiste, both as a musical project, and to Mike York and myself as people. Crescent, the closing piece on our new Teleplasmiste album, ‘To Kiss Earth Goodbye’, contains a recording made inside West Kennet Long Barrow one Summer Solstice night, and another from the springs beneath Glastonbury Tor. I live close to Avebury stone circle, while Mike is nearer to Stanton Drew, so in his video for ‘A Boy Called Conjuror’, film maker Tom Hurst brought the two sites together, flowing in space and time.”

Aubrey Burl: 1926 – 2020