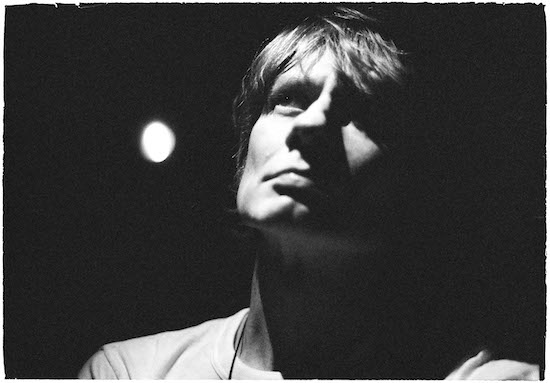

Portrait courtesy of Marylene Mey

Even among countless talented peers in the post-punk era, JG Thirlwell cut a lone figure. Combining disparate and seemingly incohesive styles and disciplines, his music as Foetus pulls in several directions to create a complex combination of sonic experiments, chance, and glorious harmonious absurdity. His ability to atomise and then perversely reassemble the familiar may have been impenetrable for some.

And even though he was cursed with rock-&-roll-star good looks, his immersive world may have proven to be a little too much for the early 1980s in terms of commercial chart success. Yet, somehow, he managed to infiltrate top-40 pop culture via appearing on the BBC playing saxophone with Orange Juice and rolling about on the floor with Soft Cell on Channel 4, all while building the Foetus empire with a slew of highly influential and successful indie albums and 12" singles.

Thirlwell’s influence as a producer, composer, graphic artist, sound designer, remixer and performer (to barely scratch/scrape the surface) runs like a golden thread through the fabric of independent music on both sides of the Atlantic. It is near impossible to trace the family tree of almost any independent music scene of the last 40 years very far without his name coming up. In the case of Einstürzende Neubauten, he was important in introducing their music to the world outside their native Berlin.

His early years saw him in the role of key collaborator with seminal artists such as Nick Cave, Marc Almond, Coil, Nurse With Wound, The The, Lydia Lunch and Swans. More recently as a composer, he has scored various film soundtracks, is the composer behind the hit Adult Swim show The Venture Bros. and FX’s Archer, and has worked with the contemporary classical music ensembles Kronos Quartet, Bang On A Can, String Orchestra of Brooklyn and many others. His new album on Ipecac Recordings, Oscillospira, is simply under the name JG Thirlwell & Simon Steensland.

Although he has been a resident of his beloved NYC since 1983, his musical story is really one of two cities. His time in London was relatively brief, but formative experiences during his tenure at the Virgin Records shop, and his ability to thrive as an artist amidst the chaos that was the Some Bizzare label, both remain the stuff of urban legend. Though his origins in Melbourne link him with the golden generation of artists that emigrated from there to London in the early 80s, and despite his extraordinary resume of collaborations, he has always pursued a solitary vision.

By gradually folding his influences from outside the confines of pop music into his musical language, he ensures that his body of work not only continues to evolve, but that it is one of the most singular and wide-ranging of our times. On paper, all the dots he joins threaten to render his efforts ambitious to the point of absurdity. However, the results show that these leaps of faith have paid off time and again, allowing his universe to constantly expand.

Here he talks us through ten points of entry into his large back catalogue in his own words.

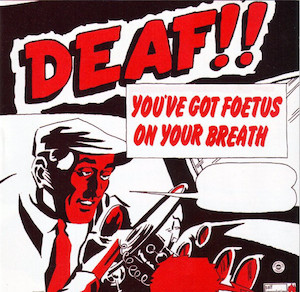

Foetus – Deaf

In my squatting days in London, for a while I lived with Keith Allen. I would sit in my room playing my synthesizers and bass guitar and making tapes. He came in one day and said: “Look, you’ve got to get out and play with other people, you can’t just be sitting here making tapes in your bedroom!” He said: “pragVEC’s rhythm section’s left and they’re looking to put something new together. You should go over and meet with them.” And so Keith connected me with John [Studholme] and Sue [Gogan]. They were dismantling pragVEC and wanted to do a recording project, but they wanted to call it by the name of their record company instead, which was Spec Records, so we made an album under that name.

While I was playing with them, being in their band, I realised it was a democratic process, but they steered the ship. You had to make room for other people’s ideas and I decided, "This is not for me." I wanted to do something where I could succeed or fail on my own merits, and be in charge of all the ideas. I decided I needed to just go into the studio, play all the instruments myself and make a record, and that was what the first Foetus single was. I did it while I was still with pragVEC, with Spec Records. We were gonna do one show, which would be opening for Cabaret Voltaire at the ICA, and then they kicked me out of the band before we did it, right before the first Foetus single came out.

I wanted to present an artefact where there wasn’t necessarily a face attached to this object – it was mysterious. I was making something more transcendent than “a musician who was in a band”, and the record was a documentation of that. I was playing all the instruments myself, but I was not particularly proficient at all of the instruments. I would take the instrument out of the box, play the overdub and put it back in the box. I wasn’t interested in practising. I was interested in making a piece of art that was a multiple, and everyone could have a copy. I think what I was doing was pretty singular to my vision and wasn’t necessarily in step with other things that were going on because I wasn’t part of a community of groups that played together.

There was the Rough Trade community with The Raincoats and Swell Maps and The Red Crayola, Scritti Politti and Delta 5 and so on, who would play together. I didn’t even play live. Mine was very much a studio-based thing which I presented behind this mask of anonymity so that I could be a bit faceless and promote it and do a lot of other things at the same time.

I recorded and mixed both sides of the first single in a day, and then I took the proceeds of that and made the second single. The second single I did in two days and then the album, Deaf. I’m pretty sure I made Deaf at Lavender Sound, which I think was in Clapham. It was an eight-track studio and the house engineer there was Harlan Cockburn and we got along really well. It had a live room. It was a cheap eight-track, maybe £8 an hour or £10 an hour, I couldn’t afford more. We worked really fast. They had an upright piano, which was great because I was very into prepared piano and a lot of the sounds on those early things are with prepared piano, using thumbtacks, alligator clips and gaffa tape.

In my mind, I had created a prejudice against using any reverb, or plate reverb, because on the first single I swamped the snare with reverb. I thought it would make it sound big but it made it sound muddy. What I discovered in Lavender Sound was recording things with room ambience. They had a hallway and a stairway, so then I started playing around with mic’ing things differently. I made a lot of recordings there with Harlan. That was where I developed a lot of ideas along the way. I wasn’t dicking around. I always was heavily prepared when I went into the studio. I had a whole notation system worked out for the songs, and I always had my little bags of tricks and sometimes I’d be picking up stuff on the street as I went to the studio: “I found this hubcap.”

By then I was getting a lot more into tape-looping and varispeed and things like that. There was one effects unit in there, which I probably used to death, and we used tape delays and tape loops, and there was a Clap Trap – all it did was make clap sounds. I had a lot of ideas, but the secret sauce was my audacity at that time, and also not quite knowing how to do what I wanted to do. I think that you’ll see that in a lot of music from that time – when you’re trying to accomplish something which is maybe a little bit grander than you can accomplish, but you do what you can do and then that’s what the result is.

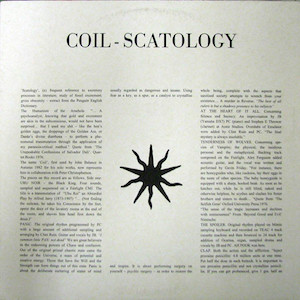

Coil – Scatology

I saw Throbbing Gristle for the first time in 1979 at the Centro Iberico. It was the first opportunity that I had to see them since I had moved to London. The show was in the afternoon. They started playing before everyone was in. They locked the doors so you couldn’t get out and it was freezing cold in there. They put out this foul-smelling gas and they had huge screens playing films of castration behind them and it was the most confrontational, amazing fucking show. So that was my first experience with Throbbing Gristle, and, subsequently, I went to see them every time they played in London.

When Throbbing Gristle’s Heathen Earth came out we had them come down to Virgin Oxford Walk, where I worked, to do a signing. It was a really weird thing to happen because at that time musicians would do public appearances and record signings at record stores, but it would be someone like Kirsty MacColl. Tons of people turned up and it was great. That was the first time I met Throbbing Gristle personally.

Later I got involved with the Some Bizzare label through Matt Johnson. Matt and I had become really good friends. We met because we were published by the same company, Cherry Red. Matt introduced Stevo [head of Some Bizzare] to my work. I vaguely knew Stevo because he used to deliver for Phonogram when I was working at the record store. He was about 17 years old and he’d come down, carrying the boxes in a powder blue jumpsuit. He was the "Futurist DJ" and he’d be getting obscure 7”s from Germany to play in his set. Later he put out The Some Bizzare Album, and it had The The on it as well as Soft Cell, Depeche Mode, Blancmange and so on. Soft Cell had their big success with ‘Tainted Love’, and then The The was signed to Epic. Matt introduced me to Stevo and Stevo loved my music.

Psychic TV were also signed to Some Bizzare, and we would run into each other at the Some Bizzare office, which was a bit of a hangout. That’s where I started hanging out with Geoff Rushton [John Balance of Coil]. We got on really well and we talked about music a lot. He asked if I’d produce them and I said yeah, that’d be great.

They’d already started a bunch of the tracks so we went into a studio and recorded overdubs and some new material from scratch. It was a lot of back and forth, and it was a good relationship. I helped them shape some of the pieces and take something that was just a couple of loops and make it a bit more fully formed.

We were using [E-mu] Emulators – it was the early days of sampling. We had very small amounts of sampling time. The first real sampling that I did was with an AMS delay machine, where you could lock in a short sound. It was only about one or two seconds of sampling time. I remember going to a studio and someone had customised their AMS so there were ten seconds of sampling time and I thought: “Whoa, this is outrageous!” You couldn’t interface a keyboard to the AMS but you could trigger it with audio and you could re-pitch the sample. We’d figure out the percentages to re-pitch the sample to get intervals where you could create a melody or a chord.

The first piece of sampling technology I owned was a DigiTech effects box that had the ability to do lock-in sounds, but you could hook a keyboard up to it. That became a staple of Wiseblood. Prior to that, Fairlights had been introduced but they were so expensive that they were not accessible to everyone. There’s a lot of Fairlight on my album Nail.

A lot of the artists on Some Bizzare hung out socially, but if there was anything that defined the coming together of those artists it was that they had nothing in common. Everyone had their own vision. There was maybe an aesthetic common ground, but, the way they manifested it, everyone sounded totally different from each other.

I had already started working with Einstürzende Neubauten and I kind of brought them into the fold. I had met with them in Berlin in 1982 and they just totally blew me away. I knew their records, but when I saw them live it was just so insane. I said: “Do you want to try and get your records out in the UK?” At first I wanted to license the ‘Durstiges Tier’ 12”. By then I had a production and distribution deal with Rough Trade for my second album, Ache. So I approached Rough Trade and I said, “I want to start this subsidiary label which was gonna be called Hardt Records.” They were down with that, and the first release was going to be ‘Durstiges Tier’.

Business-wise, I mainly dealt with Marc Chung. He said that instead of doing ‘Durstiges Tier’, they had decided they would rather do a compilation album as an introduction of their music for their first UK release. I said that would be great, and they started putting that together. At that point, I had gotten involved with Some Bizzare and I asked Neubauten: “Are you interested in working with this label?”. So I introduced Stevo to it and he loved them.

They were putting together the compilation at the same time as I was recording Hole – I remember they were sending me stuff. In downtime [from Hole] I was working on the design of the inner sleeve of the record cover and I was copying Blixa [Bargeld]’s typography and making the track titles. So we put that whole thing together and then Some Bizzare decided they didn’t want to do a compilation, they wanted to make a whole new album, which turned into The Drawings Of Patient O.T..

So we had this compilation album, which I then took to Mute Records, who said they’d love to do it. Then Daniel [Miller] said: “We’ll keep your imprint on there if you want,” and I said “No, my work here is done” – one of the stupidest things I ever did in my life [LAUGHS]. We continued our interminglings for many years after that.

Wiseblood – Dirtdish

Wiseblood was the first fruit of living in New York, after having moved there in 1983. The idea that I had for Wiseblood was it was going to be four drummers and vocals, and the first drummer I approached was Roli Mosimann. He was playing drums in Swans, and I used to watch him play thinking, “This guy is incredible." He was playing in such a prehistoric way, but with such nuance, like John Bonham. Those little ghost beats, and a little push and pull – that just made it so great. I didn’t want to steal him from Swans – I asked Michael [Gira] about it and he was OK with it. Roli at the time was setting up his own electronic music studio, and so we started bouncing around ideas, and then it ended up being me and him and it went in a different direction.

He extracted himself from Swans soon after that because he started producing. He got involved with Young Gods and I think he produced Faith No More at some point [1997’s Album Of The Year]. He was living in Tribeca, and we would do pre-production at his place. We both had those little Electro-Harmonix samplers and I would turn up with a bunch of ideas and he’d have ideas and we’d sort of nut stuff together. The first thing we did was a live show opening for Test Dept at The Ritz [which is now Webster Hall]. We said: “Let’s make a 12”." Rob Collins, who was working at Some Bizzare, started a subsidiary called K.422. The Wiseblood 12” [‘Motorslug’] ended up being on K.422, and along the way I introduced Rob to Swans.

So ‘Motorslug’ was released and that evolved into making a Wiseblood album. I didn’t have a pre-production set up at the time and it was great to be able to realise things with Roli and have that immediate gratification. We’d work on my ideas or Roli would have a sound and we’d work on something around that sound. It was a change, because by then Foetus had become something that was meticulously crafted and complex – it needed 24-track recording studios and samplers, and it became monolithic.

I find that when I start a project, it is a blank canvas, and it can be anything I want it to be. Then as soon as I’ve made one record and you go to make the second record, you have this precedent, an identity – you have this thing to live up to, or, you have this thing to surpass. And so each time I start a new project it’s liberating, because you don’t know what it’s gonna be. It could be a whole lot of things and that’s what was great about doing something like Wiseblood. First of all, it was a collaboration, which was different for me. And secondly, it was: “What is it? We don’t know yet.”

Then it started to coalesce. There was a certain point where I knew I wanted it to be… I use the words “sick”, “violent” and “macho”, and that became a bit of a millstone around my neck. I wanted to put this kind of auto imagery onto it, so the ‘Motorslug’ logo looked like it belonged on the back of a motorcycle jacket, and then there are checkered flags on the cover of the Dirtdish album. So there’s that motif that runs through it, and then it’s got an identity, and you wonder, “How do we explore this?” Each collaboration is different. The power balance is different in each collaboration. You push and pull and you find your own level and you find your own job.

Clint Ruin & Lydia Lunch – Stinkfist

Lydia [Lunch] pulling together The Immaculate Consumptive shows was the catalyst for me coming to New York in the first place. There were two shows at Danceteria and one show at the 9:30 Club in DC. The way that I remember it is that Lydia was offered these shows for Halloween 1983 and she approached myself, Nick Cave, and Marc Almond and asked whether we’d like to do it, and we all said yes.

At that point The Birthday Party had just broken up, and we’d all done things in various combinations. Marc and I had worked together with the Mambas, Nick and Lydia had written the 50 one-page plays and they’d done the Honeymoon In Red album, and I was working in the first incarnation of The Bad Seeds, so there was a lot of cross-pollination.

I had met Lydia in London through The Birthday Party. Lydia had a piano at her place, so Nick Cave and I went there to write, and we wrote ‘Wings Off Flies’. He already had the lyrics, which he’d co-written with this guy Peter Sutcliffe. He actually had a lot more lyrics and lost a bunch of them, which he did quite a lot in those days. We went into the studio and we put a version of that down. It was myself, Mick, Nick and Blixa, and Barry Adamson joined later. We also did an early version of ‘From Her To Eternity’, which sounded totally different to the one that’s on the album, which I believe I played some guitar on. Around that time I was getting involved with Some Bizzare, I was starting the Hole recordings and everyone had a lot of different things going on. I’ve noticed that Mick Harvey has said that our ways of working didn’t line up because I have a much more organised way of working and theirs was so loose. I don’t remember that one way or another, but I’d been around those guys enough to know that they had different ways of working. I used to live with Mick Harvey and his partner Katy. Mick is pretty organised. I’m glad there’s that document, ‘Wings Off Flies’. Who knows what could have happened.

I drifted away from other things to concentrate on Foetus. In 1983 I had studio time from May to September and that’s when I did Hole – ‘Finely Honed Machine’, ‘Calamity Crush’ – and a bunch of other stuff.

Also at that time Steve Stapleton [Nurse With Wound] and I had started this Sylvie And Babs album. That was gonna be just us, and I sort of drifted off to do all this Hole recording and then he ended up getting like 50 other people on there and finishing it.

So anyway, we put this thing [The Immaculate Consumptive] together and I think it was really good, it was interesting. In the show we did various combinations of playing with each other and solo spots. It culminated in one track we all played together on, and then ended with Nick playing ‘A Box For Black Paul’ solo on piano. It always drove me crazy cos he never finished it! It’s a ten-minute song. He would play it for like 6 minutes and then go “and then it goes on like that for a bit longer”, and then he’d walk off, I mean, what the fuck?! [LAUGHS] But it was great, and that was the reason I came to New York and I just stayed on.

Stinkfist was conceived back in ’83. The idea was Lydia and I were going to do a set opening for Neubauten somewhere, and somehow that didn’t happen and so we had this ‘Stinkfist’ track. Then when we moved to New York, we thought we’d expand this idea so we created a set called Swelter. ‘Stinkfist’ was in the Swelter set, and there were another four or five tracks that we made backing tracks for. Norman Westberg plays on it.

We did a West Coast jaunt and the live permutation of that was Lydia, myself and Cliff Martinez. He’s a film composer now, but he was the drummer of 13:13 and before that he was in The Weirdos and he had played with the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Cliff and I played live percussion, and I played various other things on some of the other tracks, but it was mainly percussion. Lydia did vocals, I did some vocals. We did that a few times, then we recorded.

We recorded it in LA with Cliff, and D.J. Bonebrake, Spit from Fear and Tom Surgal play on it. Back in New York, I wanted to do a remix of it so I worked on that with Roli. Instead of doing a remix where we used the multitrack, we took the two-track and ran it through a lot of outboard devices and made these weird dubbed out sections which we reassembled with tape edits – that became the main ‘Stinkfist’. Then there was a more straight version of ‘Stinkfist’, and then the other thing was the ‘Meltdown Oratorio’, which was a project I made with my first computer, an Atari 1040.

Richard Kern sometimes played films when we played live. Before YouTube, there was cable TV and there were videos. Underground filmmakers would sell their films on VHS via mail order in those days, and a way to have your films seen was to play them at rock clubs or music venues, sometimes behind the band and sometimes as standalone things between bands.

Steroid Maximus – Quilombo

The Steroid Maximus project was the result of a few different things colliding. The Foetus albums had become increasingly, maybe even 50%, instrumental. It seemed the perception of Foetus was it was this kind of pathological, dangerous, noisy, slobbering creature. Whereas I felt, “Hang on, that’s not what that is at all.” That’s part of it, but there’s this connecting tissue which is absolutely not that. So I wanted to do a project where the instrumental element got a chance to breathe on its own.

I also think it was the result of having done a couple of rock tours. The reason it took me so long to put a band together to play the Foetus material was that I didn’t think a band could do justice to all of the nuance in Foetus. Which was true: it couldn’t. But it became its own thing. It became something different to the studio version of Foetus. It became this machine that played some Foetus material.

So to start, what became the Steroid Maximus project was an opportunity to collaborate with some other people, and to let the instrumental part of me shine through. It embodied a lot of different things I was interested in, and it was creating new hybrids of music and gave me a chance to expand my studio and expand my sampling time. I was using acoustic instruments as well.

Foetus had a rule where no one else could play on it. Steroid Maximus didn’t have that rule. I said that it was music for an imaginary movie – since then that’s become a cliche. There were things on the album that were maybe informed by exotica, but there was also musique concrète and soundtracks. So it was a pretty broad canvas, and it allowed me to get that stuff out of my system and start with a new project which then got its own set of rules. The resulting albums, Quilombo and Gondwanaland, were some of the first records on the newly formed Big Cat label.

I wish I had released a Foetus album around this time. The Butterfly Potion EP is a real encapsulation of the sound that I had at that time, and ideas that I had for Foetus. If that had become an album instead of just doing the three songs, I think that would have been a really interesting record.

I had gone through several phases of technology in my studio. In the first phase, it was more of a pre-production studio, and I would work out sounds and compositions, but I’d have to take them to another studio because I didn’t have a tape machine. And then in the Steroid era, I got this Akai 12-track, which was this proprietary technology where you recorded on what looked like a Betamax cassette. It was a 12-track recorder but you could take a Midi feed out of it and sync up the computer to it. So there were 12 tracks of audio and then all of this other stuff being played by Midi live. So that was really liberating – kind of like having a 24 track at that point.

Butterfly Potion and the Steroid Maximus albums were done on that system. And so having my own recording set-up totally changed my approach, because then I could work whenever I wanted, as I do now. I get an idea and just put it down. I was also bringing people in, and say, “Come over, let’s make some recordings.”

The next technology I moved to after that was the ADAT. It was the next phase, the mid-period between tape and hard-disk recording. I think I did all of the Flow album on ADAT. Technology has always informed and changed the way that I work. I wouldn’t say I’m a tech-head, where I have to keep changing platforms all the time, but the technology is at the core of what I do. I use the program Logic to compose and record. I wish the scoring part of it was a bit more elegant but I think it’s a really powerful program. In the last few years, I’ve been doing projects where I mix them at my studio and make stems, and then I’ll remix them at another studio. When I do that I switch out to Pro Tools. I’ve been doing a lot at Gary’s Electric [studio] in Greenpoint [in Brooklyn], with Al Carlson. It’s been good to get another set of hands on it and he’s really good with subtractive EQ and doing different things with compression that I wouldn’t have done.

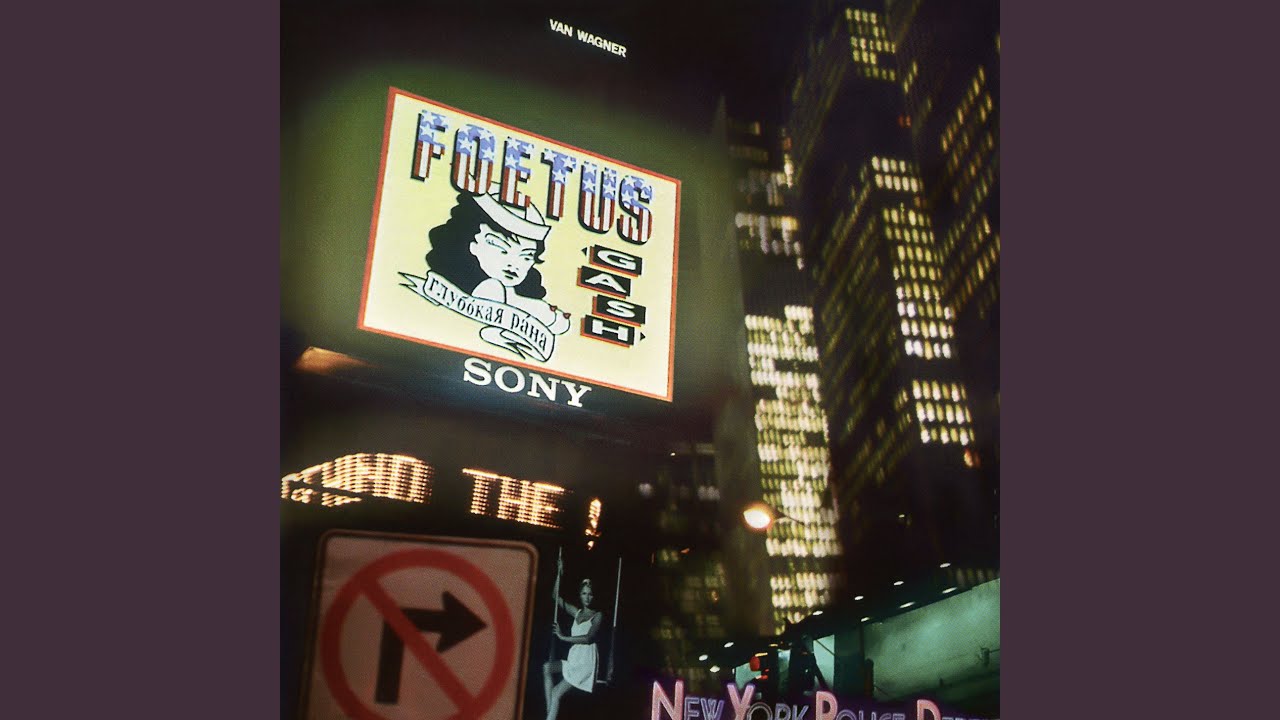

Foetus – Gash

I was signed to Columbia [Sony] by Jim Dunbar. He was my A&R guy. I heard through the grapevine that he was going to be moving to Geffen Records. I said, “Jim, I heard you were going to Geffen. What’s going to happen to me?” And he said, “No I’m not going to Geffen.” Of course, he did. Then I had no A&R guy. That was the beginning of the end for me being on Sony. But before then, there had been absolutely no compromise with the music, they just put it out. There was absolutely no [creative] pressure from Sony at all. They didn’t even know I was in the studio!

It was quite an exciting time for music in the post-Nirvana tidal wave, when there were people like me getting signed. Boredoms were on Warner. There was a lot of independent music getting signed by majors but not necessarily getting watered down, and people were selling records too. People like Pixies and The Breeders were having huge hits. So it was an interesting time. Sonic Youth were on The Simpsons for god’s sake [LAUGHS]. The culture had cracked open in some ways, and it was before Napster. It was like we were all fiddling while Rome was about to burn.

That was when I broke the Foetus rule of no one else playing on the album. I had a horn section and I had Marc Ribot play on it and Vinnie Signorelli playing some drums.

The story with the artwork is, I was recording in a studio in Times Square and after the recording session I’d come out and be in the middle of it – this is before the Disneyfication of Times Square. Before they had all the huge screens on every building there was one big screen over the New York City Police Department recruitment centre. It was called the Jumbotron, and it had Sony written underneath it. So I went up to Sony and said, “You know that Jumbotron that’s down there? I’d like to design my album cover and have it projected on that and take a picture of it, and that will be the album cover.” They said: “That’s a great idea.”

I designed this pretty simple artwork, which was kind of like tattoo flash of this topless girl wearing a little sailor’s hat. I was friends with Alex Winter and I was telling him about this concept and that we were going to do a video, and I asked him if he wanted to direct it. We filmed ‘Verklemmt’ all over the city and then got to Times Square. We had a walkie talkie and every time we wanted to film we’d say, “OK, put it up now,” and then this image would come up in the middle of Times Square and we’d film it. So that was kind of amazing. And then when the album came out we had a listening launch party at the Marriott Marquis, at the bar level with a window that looked out onto that Jumbotron. And so people were listening to the album and looking out into Times Square at my graphics. So that’s why the album looks like it does. I don’t think the pictures of it really captured it the way that I wanted it to be captured.

We did a two-album firm deal, but they weren’t going to pick up the second album, so the wheels got rolling to extricate me from the deal – that was really disappointing. I wanted to have that mechanism behind me so I could do the subsequent album and be able to tour and things like that. I just felt like it didn’t really get a chance to penetrate as it could have. By then, I was a bit over touring. I didn’t tour that much. There was the ’88 tour, and then I toured in 1990 and ’91 in the States with a band, and then right about ’95/96 for Gash. Then that was it for quite a while, and I was disenchanted with it.

I tried it again in 2000/2001, when Flow came out, and by then I was like, “No, this is absolutely not for me cos this doesn’t do justice to my music. This is not the way I want my music to be presented.” I think the last show I did as Foetus, in the band, was New Years’ Eve 2001 going into 2002. We did two nights at Mercury Lounge and that was with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs opening, so you can see how long ago that was. By then they were getting really big. That was the last incarnation of Foetus live.

What happened next was I was contacted by David Sefton [who had run the programme at the Southbank centre], who had invited Foetus to play the Royal Festival Hall. He had moved over to UCLA and commissioned me to do a Steroid Maximus concert, re-voicing the album Ectopia, which came out on Ipecac in 2002. That was the first time I felt like my music was represented in the way it could be. That was an 18-piece band. So that was like: “OK I can do this.” That’s what informed the subsequent live things, like the Manorexia chamber ensemble, and then it also opened the door to a lot of my serious work.

Manorexia – Dinoflagellate Blooms

Manorexia was partly a product of my discontentment. It’s almost like I had taken a detour into rock music or something, and it wasn’t really my intention. It’s as if I started off mocking it, and then I became it! And then I woke up and Manorexia was a reaction to that too.

The whole first album, Volvox Turbo, was actually made as one piece of music, but it had these different movements in it, and I thought it was really interesting. I decided I wanted to release it myself. This was the first thing I had self-released for a long time, so I decided I was going to do it mail-order-only through my website. It went really well, so I quickly followed it up with the second one because I had a ton of ideas. I was exploring different avenues of that musical vocabulary, but I’d already set a precedent and a Manorexia identity was starting to emerge. The second album was very satisfying. And then, funnily enough, Manorexia got the ears of people in the New Music world. That led to my commissions with Bang On A Can and The Kronos Quartet, indirectly.

My music was so dense and intricately layered that sometimes I would come up with a really interesting sound and it would just happen once, layered in with a whole lot of other things. I thought, “What if I had an avenue where that sound could actually be heard properly and have a chance to breathe?” It has its own intensity, its own sonic universe.

It reminds me of being here in my loft – especially the third album, Dinoflagellate Blooms, because there’s a lot of acoustic stuff on that that came out of just being here. I’ve been making records here for more than 30 years, but that one really reminds me of the atmosphere of this place.

By the time I made Dinoflagellate Blooms, I had been doing a lot of multi-channel installation work with the freq_out sound art collective led by Carl Michael Von Hausswolff, and some solo sound installations as well. That really interested me – working in that world where sound was immersive and listening became more of an experience. So I made that album in surround sound, in 5.1, and especially the 5.1 version has become my favourite album that I’ve made because I feel like it scratches so many itches in that way. There’ll be another Manorexia album, but I don’t know when.

The Venture Bros.

The Venture Bros. came about because of Steroid Maximus. The director Chris McCulloch was working on the pilot script and someone said “you’ve got to listen to Steroid Maximus”, and when he heard it he thought that was the perfect music, and that it encapsulated The Venture Bros. world as he imagined it. So they tracked me down. He said: “I love the music. Would you wanna write something for this pilot?” They ended up licensing a bunch of Steroid Maximus stuff and then I gave them some unpublished cues and that worked out well, and then Cartoon Network picked up the show. It was a very early Adult Swim show. They came back to me and said: “We’ve been picked up for a season. Do you wanna do this?” I had to challenge my own rigidity and put other things on the back burner. I thought, “When am I going to get the opportunity to do what I do, and present it in this whole different milieu?”

I had done a bunch of scoring before that, but this was like a really intensive masterclass. Now we’ve done seven seasons – something like 85 episodes. Then a few years ago the people from Archer contacted me. They said: “We really like what you do on Venture Bros. How do you do it?” And I said “Well, I score to picture. They give me an animatic and I look at it and we make our notes and I make original music”. They had done six seasons with just library music. They hired me and I started on season seven, and right now I’m working on season 11.

In scoring for TV you do have to be more disciplined. You have to use a different muscle, and I really like the new capacities that it’s given me. It’s made me better and broader, at what I do. But also, it’s made me approach music in a totally different way. I always have ideas about what I want to do before I turn on the studio, because I don’t really improvise. But scoring is like problem-solving. You figure out what the cue is that you have to create. It might start at, say, 16 seconds on the time code and it goes until 1 minute 32 seconds – so you know how long it’s going to be. And then you can map out: OK, it’s gonna start atmospheric, and then it’s gotta get intense, and then I’ve got to drop down because there’s a bit of dialogue, and then it’s got to be sad for another three seconds, then coming out of that it’s got to be really action-packed, then it builds to a climax and then it ends on the cut to the next scene. That will be your composition – now you’ve got to make it.

Over the course of time with The Venture Bros., reacting to the story and knowing the bedrock of the musical vocabulary that I’m starting with, I feel like I’ve created a musical world for it. The idea is to elevate the show – make it better and bring it alive – which means that sometimes it’s not necessarily a forum to experiment in. Sometimes I’m making music which sounds like soundtracks. So is it a soundtrack or is it music that sounds like soundtracks? It’s a very meta question.

There’s a lot of musical references in what I do, because there’s a lot of cultural references in both shows. There have been whole episodes where they’re in outer space and I want to reference John Williams, Star Trek and things like that, but it’ll be my take on it. So it’ll be super intense or super bombastic – everything’s ramped up to 11. A similar thing has happened with Archer, but I try and keep them in slightly different universes. There’s more jazz and more live instrumentation in Archer.

So having developed that skill, having broken through the 10,000-hour, Malcolm Gladwell barrier of where you get better at something, I then find myself applying that to other commissions. When I’m commissioned by an ensemble and I look at the instrumentation and I go, “So what do I want to do for this?” I know the emotion I want to start with here, so I’ll set up a template and I’ll figure out the tempo and I’ll start writing cells and it’ll start to map together. So I’m grateful to have gotten that skill in my arsenal. Having done a lot of work for animated programs, when I score live-action narrative film I have to dial it way back.

There are definitely people who have been turned on to me because of The Venture Bros., and I’m really proud of the body of work that I’ve created for the show. I hope for there to be more albums and I’m hoping there’ll be an Archer soundtrack album as well. I’ve also scored another cartoon called Dicktown which is short-form, 15-minute episodes. It will be on a block of programming on FX, hopefully sometime in 2020.

Xordox

I decided from the get-go that Xordox was going to be electronic. It initially came about because John Zorn approached me to do a concert at The Stone [in Greenwhich Village] in honour of the centenary of William S Burroughs’ birth. At first I said: “Oh I don’t really have anything.” But I had this Moog [Sub] Phatty that I had borrowed from a friend of mine that I had hooked up to my laptop and into my miniKORG and I was messing around with some arpeggios and stuff like that. I was messing with the filters, just enjoying doing that for the hell of it, and eventually I thought, “Maybe I should just do this.” The Stone only holds 69 people, and if it sucks no one’s ever gonna see it. [LAUGHS]

I’d been wanting to collaborate with Sarah Lipstate [aka Noveller] and I said, “Would you want to do this show? I’m just going to put like four or five pieces together and I’ll show you where to play.” She plays through tons of effects. It’s not guitar-like, it’s more like sheets of noise. it’s droney – she creates soundscapes. So, we put that together and it worked out really well and so we did a few shows like that.

I started writing new material for it and then Sarah moved to LA. I wanted to start making an album and I got some of her guitar parts on it. But the new material didn’t really call for her parts, I just wanted it to be all electronic and so that turned into the first Xordox album. It took a while to come up with that Google-busting name. Over on Metropolitan Avenue, I would see this sign all the time, that’s not there anymore, but it was for a mechanic. It said “New York Inspection”, but all of the letters had fallen off and it looked like it said “Neospection”, so that was the album title.

To perform the album live, in the post-Sarah Lipstate version, I asked Simon Hanes, who has a group called Tredici Bacci. I’ve been working with Simon for maybe five years. Simon and I also have an unnamed project which we’ve been working on for a couple of years, where we’ve written an album’s worth of material for the female voice. We’re talking to a label, and we’re slowly getting the singers together for that. The musical universe that it inhabits is what I consider to be the intersection of Burt Bacharach, chanson and the soundtrack to The Wicker Man. Haunting songs with a dark undercurrent, but also some more uptempo pieces, with a dystopian bent. He’s not to be confused with Simon Steensland, another Simon that I’m working with.

JG Thirlwell & Simon Steensland

Oscillospira – the name of the album – is the name of a bacteria. Simon Steensland is a Swedish composer who has released several albums, which I owned before I met him, and I really liked his work.

I was commissioned by The Great Learning Orchestra, which is an ensemble in Stockholm. They’re based on the Cornelius Cardew model of using some musicians that play, some people that don’t, some that can read music, some that can’t – so, varying abilities, and a lot of different instrumentation, as well as people who just want to make sound. It’s a pool of about 100 musicians. I wrote some graphic scores for them and workshopped with them. It worked out quite well and they asked me if I’d do an extended piece, so I concocted this 45-minute work for them which we performed in Stockholm.

Simon Steensland plays in The Great Learning Orchestra occasionally, and when I met him I told him, “I really like your work,” and he really liked what I wrote for The Great Learning Orchestra. He ended up doing a cover version of one of the movements from my piece and sent it to me. He said he didn’t know what to do with it and I said: “I really like this. Let’s make an album.” And so we expanded that into an album. It’s very dark prog. There’s oboe and vibraphone and marimba and violin and wordless voice and other sounds. It’s also cinematic but in a dark, chamber kind of manner. I love this album but I thought, “I don’t know if anyone’s gonna ‘get’ it, except maybe Mike Patton.” So I sent it to him [at Ipecac] and immediately they wrote back and were really into it. So I’m psyched that it’s coming out on Ipecac.

Oscillospira is out now