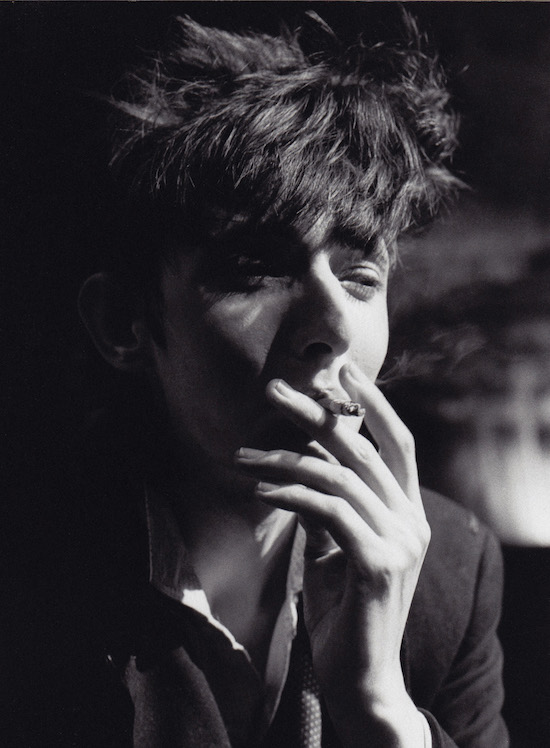

Portrait by Stefan De Batselier

Having initially gained notoriety as the guitarist of The Birthday Party, Rowland S Howard remains one of the most idiosyncratic musicians not just of the post punk years, but also of any era. Filtering rock & roll through a sonic blender to widen the scope and possibilities of his chosen instrument, Howard and The Birthday Party threw down a gauntlet that still challenges to this very day. Following the demise of the Australian post punk band in 1983, he would go on to work with a variety of people including Lydia Lunch, Crime And The City Solution and These Immortal Souls.

Drugs, alcohol and writer’s block conspired to ensure a slender solo output, and despite releasing two acclaimed albums in the shape of Teenage Snuff Film and Pop Crimes, Howard never quite got the recognition he deserved. Until now, that is. The re-issue of these two solo albums – in tandem with the series of Pop Crimes shows that have seen his material re-visited by former band mates including Nick Cave, Mick Harvey, Harry Howard, Genevieve McGuckin and JP Shilo, as well a collaborators Lydia Lunch, Conrad and Jonnine Standish, and uber-fan Bobby Gillespie – should bring Howard’s music to a deserved wider audience while re-kindling the interest of those who go further back.

Of his erstwhile bandmates, Mick Harvey maintained a close working relationship with Rowland S Howard in the years that followed the demise of The Birthday Party, and also his other projects.

“We met through the Melbourne music scene,” recalls Harvey. “Everyone found each other in 77. There were an awful lot of people playing music in their own living rooms and while there might not have been a lot of interest in them, they were aware of the groups in New York. People that I knew were getting the first Ramones albums, The Modern Lovers, and if they could get it on import, then they’d also get records by The New York Dolls and The Stooges.”

He continues: “A similar thing was happening in England, and it was an amalgamation of the idea of Europe and America in combination. There was an explosion of energy around the impulse to simplify things… to reduce them down to the basic raw elements.

“People started organising independent gigs and playing in bands, and suddenly everyone found each other. And that was when I met Rowland.”

In examining Rowland S Howard’s remarkable career, tQ spoke with many of the musicians and artists who worked with him before his death at the age of 50 in 2009. They were generous with their time and their insights have been illuminating. And while this may not be the whole story, it is nonetheless his story told via ten key releases.

Young Charlatans – ‘Shivers’

The work of an undoubtedly precocious talent, ‘Shivers’ was originally written and recorded by a 16-year-old Rowland S Howard in 1976 while a member of the Young Charlatans. Upon joining The Boys Next Door – soon to be The Birthday Party – the song was overhauled with singer Nick Cave taking over the vocals, much to the chagrin of Howard. And though Cave later admitted that he hadn’t done the song justice, ‘Shivers’ is a perfect distillation of teen angst and heartache that resonates beyond its original environment, and is the undoubted stand out track on the band’s debut album, Door, Door.

Yet for all that, ‘Shivers’ is a song of which there is, arguably, no definitive version. Speaking of the song on Australian TV in 1999, Rowland S Howard remarked wryly: “It’s just so long ago, that it doesn’t even seem like it’s anything to do with me. I feel like I’m playing a cover version.”

Harry Howard [Crime & The City Solution/These Immortal Souls]: The song was such a shifting thing that it went on take different forms. At the time it was written music was changing very quickly. The Young Charlatans version is very much of that time – or ahead of its time in its approach for Australia – and by the time it got to The Boys Next Door, then musical sensibilities had completely changed again. But people still knew that it was a good song, and it’s one that survived all these stylistic changes.

Mick Harvey: It’s got some odd symbolism in it. It’s quite an achievement for someone of that age to write a song like that.

Genevieve McGuckin [These Immortal Souls]: Rowland wrote ‘Shivers’ when he was 16. He was in the Young Charlatans in Australia, who were very much loved. He wrote and he sang, and when he joined The Birthday Party, it was on the understanding that he would get to sing it as well. He really wanted to sing and write songs because that was where his heart lay. He always expressed himself and he said that he expressed in music all the things he couldn’t express in every day life.

MH: We were doing a version of it with [HTRK vocalist] Jonnine Standish singing it in France [as part of the Pop Crimes tribute shows] and I said, "I’ve always been curious about that first line of the second verse, ‘I keep her photograph against my heart/ For in my life she plays a starring part…‘ But shouldn’t that be ‘the starring part’?" And she said, "Yeah, it should be, but remember he was 16 when he wrote it. No one’s playing the starring part in anyone’s life when they’re 16." And I thought, "Yeah, that’s right!"

HH: It proves that the premise of the song is so good that it’s always relevant. You could do a new version every five years that suits the time and the place. I don’t think there can ever be a definitive version of it because it was never quite pinned down. It’s an elusive song.

The Birthday Party – ‘The Dim Locator’ from Junkyard

(1982)

By the time of The Birthday Party’s final album, Junkyard, the band had undergone a profound metamorphosis. Gone were the new wave flourishes of their first incarnation, and the later excursion into mutant punk funk, for here was an uncompromising album that gleefully collided elements of the blues, jazz, battered and bleeding rock & roll, dread, perversion and outright menace. The only solo composition on the album from Howard, ‘The Dim Locator’ perfectly displays his talents as both guitarist and lyricist. The lyrics – “Inanimational items elude I, and/ In-an-emotional-motion I swallow my/ Motive of quicker location is slammed/ My dim chance of skipping this thick world is thin”- scan like an opiated Syd Barrett, while his guitar increases in intensity from twisted riffing to outright chaos.

MH: The guitar interplay was a really big part of The Birthday Party’s sound. We’d moved right away from classic blues rock because the blues were the foundation of heavy rock. The influence of blues on rock is all-pervasive, really, and I suppose we helped get rid of that. There were others who had started earlier, like Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd of Television.

Bands like that were hugely influential, but really, Rowland developed his own sound. While I was being Mr Jack-Of-All-Trades – even though I was on the guitar a lot – I really devolved from normal guitar playing as well. I don’t think I played a normal formation chord for about four years or so. When I came back to playing acoustic guitar with The Bad Seeds, I was like, ‘Hmm… How do I that again?’

Nick Cave: Rowland S Howard’s guitar sound defined a generation. He was the best of us all. His influence continues to reverberate, down the years, to this day. He was truly one of the greats.

Henry Rollins: On 30 March 1983, The Birthday Party played two sets at the Roxy in Los Angeles. I stood in front of Rowland to get as much of him in the mix as possible. It was like he was an extension of the guitar. He seemed to generate the sound from within himself. When he wanted tremolo, he would shake his entire body.

He seemed at times like he was being attacked by the music. He was going through this incredibly intense experience; the three other people onstage seemed on a different planet. I had never heard sounds like the ones that Rowland made that night. To this day, I think he’s one of the most amazing musicians I’ve ever seen or heard.

HH: Those Junkyard sessions were chaotic and there were spells where nothing was happening, but when they had something, then they’d work really fast. They’d been working together for a long time by that point, so they knew exactly what to do.

MH: The sound of The Birthday Party evolved gradually. His style in 78 and 79, was pretty much on the way there, but he arrived at that sound – as you do pretty much anything with artistic pursuits – by choosing his weapons well. I think that when he combined the Fender Jaguar and the MXR Blue Box guitar pedal, he found the colour of the sound. It was very simple; a lot of guitar players these days use so many pedals, but Rowland realised he could create what he wanted to just using blue and yellow. Those were the colours of the pedals he was using.

Finding the Jaguar with the whammy bar and discovering what he could do with it, and how it felt and how he could lean into it, was all part of him finding his weapons and then using them. His taste in melody was already formed in 1978. It wasn’t blues-based; there were a lot of minor chords and chromatic patterns that made you go, "Whoah!" Suddenly you were in Rowland World and it sounded like nothing else.

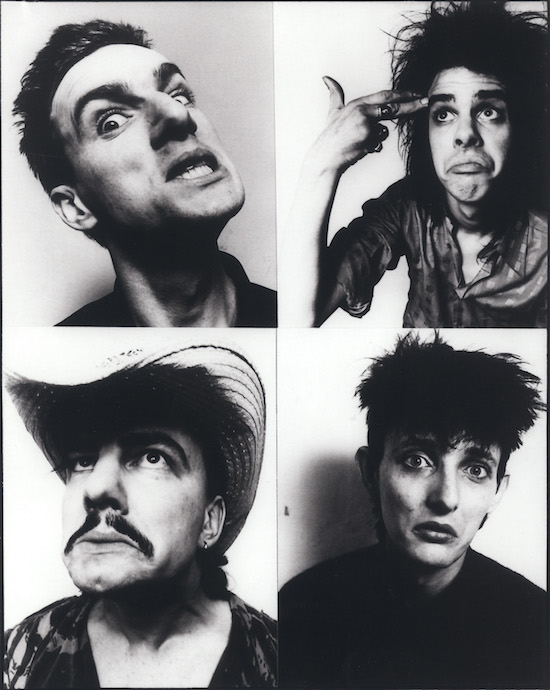

The Birthday Party portrait by Bleddyn Butcher

GM: He really made his guitar howl. Seeing The Birthday Party was always an event and it was always really exciting. His playing was melodic and it was restrained, while at the same time being incredibly over-the-top. It was all these opposing things put together. He could play just one chord and you’d just know it was Rowland.

Daniel Miller [Mute Records]: They were a tight band, but they were also pretty unusual. And they got more and more chaotic in the ensuing years. Rowland was the one that I gravitated towards because of his incredible style, his look and his unusual performance, which was really unusual. He was the one who captured my attention at the beginning the most. They didn’t sound like a rock band, really.

Jonnine Standish [HTRK]: HTRK back in the early days (and even now) was into the idea of subverting the notion of a ‘rock band’ especially the motifs of the ‘gang’ in a perverse kind of way. I think Rowland really liked that and could relate to that, especially with his involvement in The Birthday Party.

HR: I’ve been listening to Rowland in all his different incarnations for decades and never once does he play anything straight. He was inventive without limitation, as if he could not be otherwise. Everyone in The Birthday Party was singular and tremendously talented, but it’s Rowland who was truly astounding.

DM: There are a lot of guitarists and songwriters out there, but I think Rowland was on a completely different level. I remember going a The Birthday Party recording session at Hansa Studios in Berlin and Rowland playing these fairly long notes. As they faded away, the sound of the amp and the general background noise came up, and the engineer was trying to put a noise gate on it, so that those sounds would disappear. And Rowland had a big argument, going, ‘No, don’t do that! I want that! It’s part of the sound. Even when there’s no guitar there, that amp sound is part of the sound!’ He took the entire sound and took it somewhere new.

GM: After the first couple of years, Nick wanted to stop doing Rowland’s songs because he wanted to take more control. That was very difficult for Rowland.

And Rowland felt he hadn’t been writing proper Rowland songs because he was trying to write songs that Nick could sing, which is ridiculous; you can’t write songs for someone else like that because he wrote about such personal things. And because they were dealing with Rowland’s emotions, they would’ve been difficult for Nick to sing them anyway.

MH: Things were strained with Rowland for a while. He and Nick had been taking a lot of drugs, so the communication wasn’t that great. When we came out of The Birthday Party and then when The Bad Seeds started, I think Rowland felt resentful about it. In fact he never really felt OK about it.

He talked himself into the notion that The Birthday Party were having a bit of a hiatus and that it would continue later. But that was never the case; he put that into his own mind. Maybe, at the end of the last tour in Australia, he and Nick said something like, ‘Yeah, yeah. We’ll do something.’ But he and Nick never really re-kindled their friendship. They were OK with each other, but they never really saw each other or spoke properly again.

Rowland S Howard & Lydia Lunch – ‘Some Velvet Morning’

(1982)

Propelled by an intoxicated sensibility, this imaginative re-working of Lee Hazlewood’s bizarre and eldritch collaboration with Nancy Sinatra marked the beginning of a working and personal relationship that would last decades. Crucially, this reading ramps up the weirdness of the original to take the song into altogether new territories.

Lydia Lunch: I learned of The Birthday Party when I was living in Los Angeles, maybe around the time of their first or second album. Not long after that, I was in New York and they were playing. So I ran to the club and I ran backstage and pledged my adoration to Rowland saying, ‘You’re amazing!’ I couldn’t believe he knew who I was and that he’d heard Queen Of Siam and Teenage Jesus. We immediately proposed that we do ‘Some Velvet Morning’.

I didn’t know anybody at that time who knew about Lee Hazlewood, and immediately we were conspiring! We knew we were going to work together and it was instant friendship. It did feel pre-destined. I said, ‘I’m coming to the UK to work with you!’ It was instantaneous; there was no doubt.

MH: It has a drunken quality because the tempos are shifting all the time. It’s funny, when we came to do these Pop Crimes shows and started to rehearse this song – and I hadn’t had a chance to listen to the recording to remind myself what I’d played. Harry Howard was saying, "The feel is all different! It’s different from how it is on the recording!"

So I said, "Well, I’d better get home and have a listen to the recording." And when I listened to it, I was like, "Whoah! That’s really… Whoah!" Because it starts slowly, then it speeds up in the first verse, then it slows right down and then speeds back up again when Lydia starts singing. It’s very deliberate. It’s only the vocals that are at the right tempo. But it’s very consistent in the way that it’s formed.

Portrait by David Gruchot

LL: What was interesting was the economy of his playing. So many people overplay. It kind of reminds me of spoken word, in that the power was not in the rat-a-tat-tatting; the power is in the pause. So the beauty of his music was really in the space. So many of his songs had that: the space of the notes, the space of the friction, and it was a very unique style; it was very ethereal and magical.

It’s that power of knowing when to play a note and when to not. But I can only really compare it to the spoken word. Or good sex! You’ve got to know when to hold it or when to fold it!

HR: I think one of Rowland’s best qualities, besides his technique and endless supply of amazing sounds, was his emotive economy.

LL: It was wonderful to be in the presence of such a dandy, who could have almost been from another century. He was so poetic; it was like being near Baudelaire or Rimbaud, and he had an ethereal, otherworldly presence.

JS: He had an unassuming kind of sexuality you can’t put on; you either have it or you don’t. I had a subtle sarcasm and was a carrier of the pop genes that Rowland also carried. There’s a deadpan romance that Rowland and I shared. We had so much in common, the more I think about it.

Einstürzende Neubauten with Lydia Lunch – ‘Thirsty Animal’

(1982)

Always pushing the very boundaries of music, here industrial pioneers Einstürzende Neubauten team up with what would become the collaborating team of Lydia Lunch and Rowland S Howard. The results are an unholy amalgam of mechanised noise, spoken word performance and the redefinition of the possibilities of the guitar.

LL: Rowland and I started doing these improvisational vocal duets, and when you throw that nudity onto the stage, it’s going to be either really amazing or a terrible piece of fucking shit. It’s a bold chance you take, because if you have a crappy sound of the guitar or the drummer dies on stage, you still do the same songs and you can either do them badly or you can do them so well.

But when you’re doing something that is immediately coming out of your blood and your brain, it’s a challenge. It was a good lesson in – I don’t want to say ‘humility’, although sometimes I was humiliated not doing it with Rowland – early improvisational music and spoken word.

I don’t think the rest of The Birthday Party liked it; too bad! We were experimenting and they were the best band in the world then, but what are you gonna do?

I think that’s what led to ‘Thirsty Animal’, because I don’t remember it being a composed piece.

MH: Rowland created a lot of atmospheric noise and it was really low and rumbling sometimes. He got a real noise going. It wasn’t musical and a bit unidentifiable.

These Immortal Souls – ‘Marry Me (Lie! Lie!)’ from Get Lost, Don’t Lie

(1987)

Formed in London in 1987 after Howard had played in Crime And The City Solution with bassist brother, Harry, and drummer Epic Soundtracks, they were joined on keyboards by Rowland’s partner, Genevieve McGuckin on keyboards. The inaugural single release from These Immortal Souls and the opening track from their debut album, Get Lost, Don’t Lie, this is very much a summation of Rowland S Howard’s career to date whilst pointing at what was to come.

GM: Rowland wrote in bits, and I think the words came first. I thought it was catchy, but strange. A lot of Rowland’s songs were very arranged and I remember we rehearsed it a couple of times and played it together at home, which is when I ended up playing piano. He’d come to me with the words and say, "What am I trying to say?" And I’d think, "How could you not know?" Because it was so obvious! And then he’d say, "Is that what I’m trying to say? I think so…"

JS: Rowland was very deliberate with his song writing, especially the lyrics as far as I could tell. He would do a lot more thinking than, say, notepad scribbling. He would allow the riddle to unfold in its own time. He also had Genevieve McGuckin as a brilliant sounding board to talk about his lyrical themes. He was even known to say, "What do you think I mean by this, Gen?" And she would sometimes have a better idea and knew him better than he knew himself!

HH: That song came out of The Birthday Party and a John Peel session, which was a stilted version which Rowland developed. When he handed it over to me and [drummer] Epic [Soundtracks], it then became more of a drunken waltz.

’Marry Me (Lie! Lie!)’ was the first song we did in These Immortal Souls and it probably set the pattern, in a lot of ways. It was an odd song for Rowland, as he was playing a secondary role to the piano; he was playing a rhythm role. Another thing about that band was that we recorded that first album before we played live, so I think we hardened up by playing live. Rowland’s guitar attack became more focused and more aggressive, and he strived to make quite the impact on the listener. Some of the approach on the first album was bit rambling and that sharpened up when we played live.”

GM: One thing that occurred to me when revisiting his songs is just how much I love his words. He was bloody great. He had a great ability to place really complex and contrary feelings in a very poetic and clear-cut manner. it’s not overly poetic or purple prose; I think his words simply hit the nail on the head.

JS: If you have ever seen any of Rowland’s lyric notebooks, they are so very neat and signed and dated for each song like they came out fully formed. He was writing down his songs as if these notebooks would have an audience themselves.

These Immortal Souls – ‘King Of Kalifornia’ from I’m Never Going To Die Again

(1992)

There’s a convincing argument to made that Rowland S Howard’s work with Lydia Lunch on 1991’s swamp-influenced album Shotgun Wedding had a bearing on what was to immediately follow in the shape of These Immortal Soul’s second album, I’m Never Going To Die Again. On top of that, it showed that These Immortal Souls had now coalesced as cohesive working unit in a way that had eluded them at their inception. As evidenced by ‘King Of Kalifornia’, the difference in the band’s two albums is undeniable.

GM: This was a big leap forward. When we made the first album, we never really played together live. So we made the album before we were a band, and it was made in bits on borrowed and begged studio time. We’d have half a day here and a day there. We started off with different people that we gradually changed, so it was a very fractious process.

We started touring, and as it is with people when you start playing live, we got better and better. We got into a groove where you could be quite percussive and get tighter and tighter.

HH: We recorded that first album before we played live, so I think we hardened up by playing live. Rowland’s guitar attack became more focused and more aggressive, and he strived to make quite the impact on the listener. Some of the approach on the first album was bit rambling and that sharpened up when we played live.

These Immortal Souls – ‘Hyperspace’ from I’m Never Gonna Die Again

(1992)

Here is Rowland S Howard as the complete package: singer, guitarist, co-songwriter and co-producer. The sound is widescreen, his guitar still rooted in its characteristic cheesewire slice, but here taken to broad extremes. And his vocals are coloured by a steely determination and focus that display his growing talent in this area.

HH: ‘Hyperspace’ is an odd one. It had quite a long history. It started off in another form and it got re-written several times. Rowland kept working on it, and he was really into the idea of hyperspace, but he kept at it. But it was an odd one for us because it had those anthemic drums.

GM: The drums in this are amazing. It’s a lot of fun to play ‘Hyperspace’. It’s sort of a driving song and the words are just brilliant. All I have to do is play the same thing over and over with power chords on the organ. I do like playing this; it’s very in-your-face.

HH: Some of the lyrics reminded me bit of something that Alice Cooper might have sung on Million Dollar Babies. They were quite rock, but in a glam way. They weren’t typical Rowland lyrics where he wore his heart on his sleeve; he was rocking it up, basically.

HR: One would be remiss not to mention what a great singer he was. His voice and his phrasing were as unique as his guitar playing. Also, his production work and playing on HTRK’s Marry Me Tonight album is remarkable.

‘Dead Radio’ – Rowland S Howard from Teenage Snuff Film

(1999)

One of his more ethereal numbers, its spectral qualities conjure up images of vistas, grime and violence at the heart of many a spaghetti western. Indeed, it’s not hard to picture him working with Ennio Morricone after you hear this track.

MH: Rowland wasn’t an enormously prolific writer. I think that once he didn’t have a band to use as a vehicle, it was probably harder for him to work. He’d hold on to things and then he’d refine them, so he’d come up with about two or three songs a year that he was happy with. And that’s just the way it is, sometimes. Robert Forster is the same; he writes about two songs a year, maybe three. Some people are like that; some write a song a day. It just took him a long time to put songs together.

LL: If you think he knew how to hold a note, he also knew how to hold off writing too many songs! I don’t know if he had any spare songs, and for [joint 1991 album] Shotgun Wedding it’s not as if we had too many songs to choose from!

We wrote those songs and that was the perfect amount. It’s bookended by two covers – [Led Zeppelin’s] ‘In My Time Of Dying’ and [Alice Cooper’s] ‘Black Juju’ – which just make sense for the theme, and it was like massaging the songs out of him. But every song was perfect, and every guitar part was perfect, and all the lyrics were perfect. It’s not how long it takes or how much you do; it’s how exactly each song duplicates what you had in mind, and then goes beyond that.

MH: It was then ten years before the next album, and that was a struggle to get those few songs out of him. The last two albums were written after we started recording, and one of those was like a track that had been a B-side from around Teenage Snuff Film. So he only had three new songs. But he became more focused and he wasn’t going to do anything that wasn’t critical to what he wanted to say.

Rowland S Howard – ‘Sleep Alone’ from Teenage Snuff Film (1999)

Howard’s full range of talents is in evidence here. The extraordinary guitar playing paints from a wide palette as notes are throttled and sustained and chords are slashed, torn and frayed as Howard the singer rages his existential angst with a delivery that elicits empathy and sympathy.

MH: Rowland was trying to do something open and different here. It came out of the way we recorded the album, which was really just me and Rowland. [Bassist] Brian Hooper had turned up the week before and it was going to be a three piece recording with guitar, bass and drums, but then he had to pull out, so we recorded eight of the backing tracks with just me and Rowland playing. It was just guitar and drums.

There was loads of space and you can really hear that. Some things were overlaid, such as violins, bass and some keyboards, but there was just… space. And we left it open; it was a great experience recording those basic tracks together.

This was one of the songs recorded when Brian came in. He co-wrote the bassline and we had to get him in, because he was a very unique bass player. He was really important to the feel of the song, so we couldn’t just have him come in to overdub his parts. He came in and did this and ‘Exit Everything’. We did those as a three-piece, and there’s less room in those songs.

Rowland S Howard – ‘(I Know) A Girl Called Jonny’ from Pop Crimes

(2009)

There’s a sadness attached to Pop Crimes. Released just two months before his passing, this is undoubtedly Rowland S Howard’s most compelling and consistent solo album, containing this late period example of his ‘pop noir’. Rooted with a melodic sensibility and a feeling of melancholy that’s seemingly caused by a happiness that’s just out of reach, ‘(I Know) A Girl Called Jonny’ continues to linger.

MH: [Rowland S Howard’s bass player] Conrad Standish always says this thing that Rowland was in love with his wife, meaning Jonnine. I don’t really know what was going on, but they were really good friends and they wrote that song together.

JS: ‘(I know) A Girl Called Jonny’ has really become something of a signature song for Rowland. I can’t quite believe it. I’m so happy about the connection fans have to the song. We had a lovely chemistry as friends and it’s a special luxury to have that friendship immortalised in a song, especially now a decade on.

MH: It’s kind of catchy, and it’s a pop song, in a way. It’s got a level of accessibility that maybe some of his other songs don’t have.

JS: It has a classic 60s pop theme of artist and unattainable muse, which of course Rowland beautifully embellished with pulp fiction imagery. It was really fun to play the acting role as the disasteress.

While working on our duet, we met up in a cafe in St Kilda for coffee and Rowland excitedly passed me a notebook with what he had written so far. In capital letters quite neatly were two of the main verses and the chorus, as well as the infamous line, "pashing with the devil at the bus stop". It’s a very innocent pop song with an almost X-rated chorus, really. I don’t think I really took that in enough at the time. He was understandably blushing when he passed me his lyrics on that piece of paper, ha! I have these lyrics from this notebook framed on my wall now to remember that day with Rowland.

MH: What’s Rowland S Howard’s legacy? Oh, I can’t answer that; I’m too close to it.

DM: Rowland was totally original; that’s pretty obvious. I remember seeing Radiohead pretty early on and thinking, Johnny Greenwood has been watching Rowland Howard very carefully. I mention that to other people and they say, "Yeah, that’s right." It makes sense.

HR: Rowland was a true one-off. The more intently you listen to his playing, the more you discover. He was really that good.

LL: Already beyond this world, he should be remembered as a magician of sound.

Pop Crimes and Teenage Snuff Film have been reissued by Mute and are out now