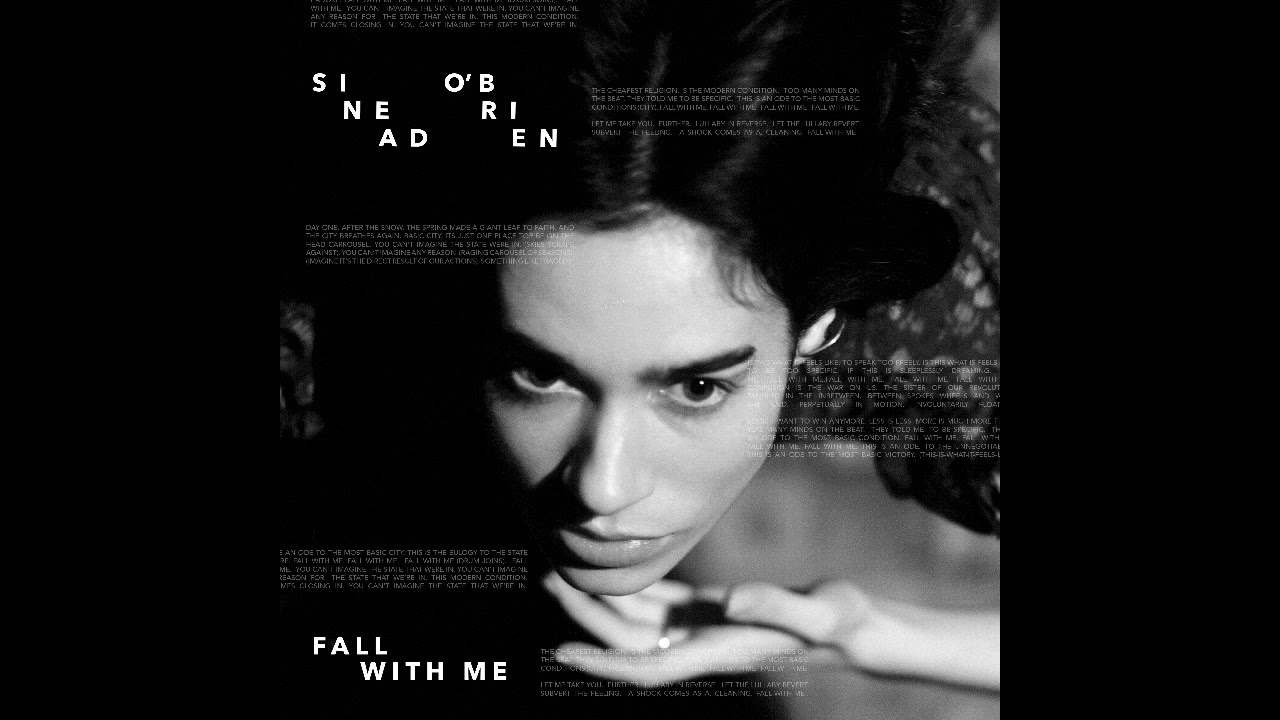

Photo by Zac Mahrouche

Sinead O’Brien’s first musical memory is of her mother’s Ford Puma. “She’d drive us to school every day and the only tapes she had were The Beach Boys and Vivaldi,” she says, sat calmly in a cranny of a hectic Soho pub. “Every day it was the same choice, Beach Boys or Vivaldi. I thought that was wonderful because I love repetition, I love to reinforce things. Recently I had this one jacket that I wouldn’t stop wearing, it was covered in diamonds everywhere and I stapled a cigarette onto the lapel. I kept stealing Swarovski crystals, anything I could find, and it was getting more and more encrusted, then one day an intern at work was like ‘I swear to god, if you wear that jacket one more time…’ It was like ‘excuse me!’” O’Brien laughs, “’I’m reinforcing my idea, don’t you understand?’”

O’Brien is a senior womenswear designer at Vivienne Westwood, where she’s worked for the last six years. “I cover the whole design process which is quite massive,” she says, her speech quick, concentrated and peppered with pride. “I do fabric research to find the ideas that I want, attend all the fittings, work with the tailors, work with pattern cutters to get what we want.” O’Brien has worked closely with Westwood herself, and the designer takes an interest in her interviews. “It reminds me of this old relationship that painters would have had with their mentors,” she says. “She’s passed on all this information to me, the types of things that are never written down. I feel like I was one of the last people she’s worked that closely with.” Her dedication to design is intense. The time she spent studying and working to get where she is now “was extremely testing of my personality,” she says. “Studying fashion design is exactly what it sounds like, staying up all night for three years straight. It may sound pathetic, but any hobbies got left to the side. I enjoyed writing my thesis though, Fashion’s Traditional Yet Cutting Edge Method of Using the Past to Feed the Future.”

Living in Paris while she interned for John Galliano, O’Brien began finding the time to write things down. There was no grand purpose other than to document her life there for friends back home, but she was sowing the seeds of what would some time later pull her into a second, parallel life. “There I was, going along in the career that I wanted to have, I had been in Paris, I was working for Vivienne Westwood. And then eventually this other thing just slapped me in the face, and I just doubled myself. I was going to say divided, but absolutely not. My mum once told me that when you have another child you double the love,” she laughs. “So I decided to double myself, and to exist in both worlds.”

That ‘slap in the face’ was O’Brien’s agreeing to perform her writing at the ‘New Gums’ spoken word night at the Brixton Windmill. “It was during a phase I was going through when I was just saying yes to everything,” she says. “I had been feeling a bit introverted and limiting myself. I mapped out my routine one day and it was very upsetting, so I started to say yes to things to get me going in more spontaneous directions.” The evening before the show she recruited Niall Burns of the band Whenyoung, a friend since childhood in Limerick and then her flatmate in London, to provide backing on guitar. She threw references and adjectives at him – ‘Television’ or ‘jangly’ or ‘David Lynch at night driving really fast’ – and he came up with guitar lines around which she started to weave her words. She suffered no nerves at the gig, partly because she had the flu and was on a heavy dose of painkilling medicine, but partly because performance is something that, for whatever reason, has never phased her. “When I was young I did things like lifesaving exams and piano. I did some acting for a while too. None of those things made me nervous either. So maybe it all stems back to that…”

Though she practised piano from the age of six, until the demands of fashion design took over at 19, O’Brien had never explicitly considered writing music of her own. In fact, it had the opposite effect. “I loved it and everything, but it wasn’t really a form of expression to me, it was more of a drill,” she says of lessons under an austere and strict antiques collector ‘with the look of Bianca Jagger mixed with Elizabeth Taylor’. “I learnt in this really strict way. ‘You learn the classics and you play the classics’. I never thought of it as a form of new creation.”

You sense that it is inevitable, however, that O’Brien’s words would end up put to music and performed. Even when she first started writing back in Paris, she says she felt like there was melody in what she put on the page. Later down the line, John Cooper Clarke invited her to support him on tour on the condition that she perform without any backing whatsoever – “he wanted to reinforce his idea of selling out theatres only with poetry, which I thought was a dynamite idea even though I was quite upset that he wouldn’t let me have any music,” she says. “A few of my friends came to that, and they said it still sounded like there was music. That was my intention.”

More crucial than either that gig, or even the Windmill show, however, was her meeting Julian Hanson, with whom she now writes and performs (Burns’ role was a one-off). After first meeting one night in the MOTH Club in Hackney and swapping numbers, Hanson “started to come into my life as a dripping tap,” she says. “He used to come over sometimes and he’d play the guitar on the floor of my tiny box room, and at some point I just started reading against him playing. It felt really good, I think we were a bit shocked about what the clash ended up being. I hate the word random, but when you put two random things together, sometimes it takes a bit of a while to understand what happened – if it’s a good thing or if it’s just a nothing. But I think that once we started to lock in, and work together, at the same time as becoming really good friends, it kind of made sense.”

From there, O’Brien and Hanson, who is based in Nottingham, as well as London-based drummer Oscar Robertson, began endlessly swapping references and trading long voice messages as they built upon that brilliant early collision, O’Brien’s instincts for finding the music in her writing growing sharper and sharper as her and Hanson’s understanding grows. “Every single day, every hour I have spare, I’m writing,” she says. “Whether it’s in my notebook or my phone or whatever, and I’m always listening to music. Sometimes Julian sends me little snippets of guitar, and I start to get a feeling for what might be the hook of a song. As soon as I have something where I can imagine what it looks like, I book a train and go see Julian in Nottingham, or he comes to me. He never listens to the playlists I send him, he wont listen to any of the references I have, which is brilliant, because he can never hear what I heard. We question each other a lot, we carve and shape things together, intrusively in a way, but it’s very welcome and wanted in that way. It all comes down to the fact that I love everything he does.”

In a relatively short space of time, and over a relatively slender amount of songs, O’Brien and Hanson have established a sound that is urgent, demanding and ungrounded, music that keeps shifting and sprawling as it evolves. Her new EP, like standout single ‘Taking On Time’, was recorded with Speedy Wunderground’s Dan Carey, whose abilities push things even further. “At the risk of sounding like a witch, there’s so few words exchanged when we’re in the studio with Dan.Take this how you want but it’s a feeling, you cant just be put together with somebody and to get a good result. I have a really, really, really deep connection with Dan, like [I have] with Julian, like with my best friends, I only really have people like this around me, and then everyone else can fuck off!”

The EP is brilliant, but it also serves as a moment both to take stock of an already remarkable body of work, and to consider what’s next. She sees the four tracks of the new release as opportunities to look ahead in four different directions, in an effort to map out her next move. She has “a strong feeling” about which path she’ll take, but after much pressing refuses to reveal which. “What would be the point in me saying that?” she says with a defiant smile. “That’s like putting a gold star sticker next to one of the tracks. My mum and dad are split, the label are split, the manager is split, and it’s always between the same two, but I’ve never told anyone what mine are. I’m interested in unbiased reactions, do you know what I mean? I’m interested in peoples’ behaviour and what people say and think. I want a pure reaction.”