When I first picked up Gravity’s Rainbow at the age of 19, I found it exhilarating and bewildering in equal measure. A hybridisation of historical text, scientific theory and counter-cultural encyclopaedia, rendered in hyper-dense prose that was often closer to the delirious highs and lows of an acid trip than a conventional novel, the 760-page archetypal postmodernist beast nevertheless defeated me on my first attempt.

It sat on the bookshelf for two or three months whilst my mind got over its indigestion. When I picked it up again, I sailed through the remaining two-thirds drinking in all the wonder it had to offer. Probably more than any other novel, Gravity’s Rainbow is cited by readers and authors alike as being the book they would most like to finish reading, but whose end has always proved elusive. For those willing to invest the necessary time, however, and who also accept that the novel’s richness is almost impossible to appreciate in a single reading, the rewards it offers far outweigh the initial investment of effort.

Once you get past the initial difficulty, it becomes endlessly entertaining in a way that may only ruin your appreciation of less ambitious authors. Pynchon’s work also repays subsequent re-readings more than any other novelist I can think of, and revisiting his writing offers a lifetime’s engagement for those so inclined. Pynchon also opened up a whole world of other writers for me – John Barth, William Gaddis, William H. Gass, Robert Coover, David Foster Wallace – and his introduction to Jim Dodge’s Stone Junction (“like being at a non-stop party in celebration of everything that matters”) likewise served to acquaint me with another author whose work struck a deep chord.

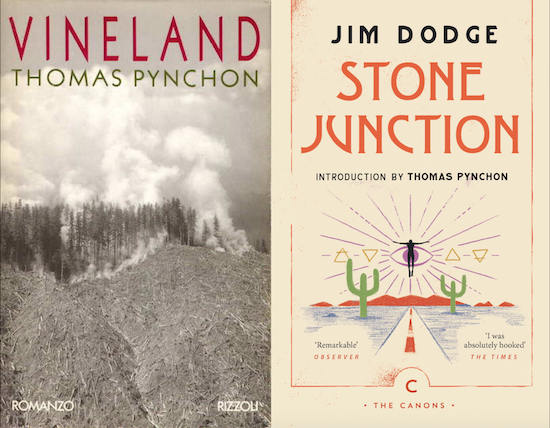

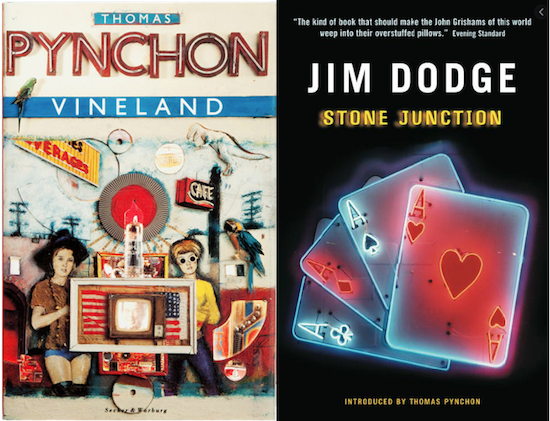

The seventeen years between Gravity’s Rainbow and Vineland, had critics chomping at the bit, yet the book itself disappointed many. The author’s penchant for anonymity, combined with the lengthy interim between books, had critics speculating all kinds of possibilities. Salman Rushdie wrote in the New York Times in 1990: “We heard he was doing something about Lewis and Clark.”

Other rumours concerned a 900 page novel about the American civil war, and some academics were holding out for nothing less than a postmodern equivalent of Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. Vineland, with its cast of oddball Californian characters looking back from the perspective of the Reagan era to the 60s, with its dearth of ‘serious cultural allusions’, favouring instead a pop-culture brew of real and imagined musical, filmic and televisual references, was not that book.

Reviewers asked: was this what Pynchon had spent 17 years writing? In retrospect, it now seems likely that Vineland was only one of the projects that Pynchon had been working on during those 17 years. Two weightier works followed. Mason & Dixon appeared seven years later, and Against The Day another sixteen years on from Vineland. Against The Day is arguably the postmodern Finnegan’s Wake that critics had hoped Pynchon would one day produce, and along with Gravity’s Rainbow, is one of Pynchon’s two true masterpieces.

Yet they are but two novels in the total continuum of Pynchon’s universe. Viewed as part of a greater, connected work, Vineland remains the most human and emotionally poignant of Pynchon’s novels, whilst simultaneously being a far more sophisticated examination of how the changing nature of the recorded image impacted upon the ideals of the 60s than it at first appears. It is also, along with Pynchon’s The Crying Of Lot 49, a far more accessible place for the uninitiated to begin.

Nostalgia in general, and for the sixties especially, is rightly viewed as critically suspect. Nostalgia for an era like the 60s is often felt more strongly in times like the Reagan era or the current Trump presidency due to the stark contrast between idealistic hope and reactionary control. It could also be argued that the sixties continues to exert an attraction as it offered a time when it was perhaps easier to tell the ‘bad guys’ from the good. Certain eras do exert a valid particular attraction in both cultural and philosophical terms, however.

1960s America was a time when radical change felt possible, even if only for a short time. Experiments with LSD and psilocybin appeared to open up new possibilities for personal growth and spiritual understanding. Seeing one’s personal psychological make-up in terms of imprinted possibilities, rather than absolute certainties, played a huge role in American youth’s rejection of a paradigm that included sending many off to their deaths in Vietnam. As Mucho Maas (a character from Lot 49) says: “No wonder the state panicked. How are they going to control a population that knows it will never die?” Looking back at those times, from the perspective of 1984, the year of Ronald Reagan’s re-election, Vineland is no simple exercise in longing for a simpler, more idealistic era, but something more complex that identifies the factors that contributed to the fading of those beliefs, whilst recognising the complicity of its characters (and even its author) in that process.

Hippie musician, Zoyd Wheeler, lives in California with his 14-year-old daughter Prairie. Coerced by villainous federal agent, Brock Vond, to stay away from Prairie’s mother, Frenesi Gates, Zoyd must “do something publicly crazy” every year in order to keep collecting his benefit cheque. During the 60s, Frenesi was part of a militant film collective known as 24fps that attempted to capture fascist transgressions on film. Doomed by her mutual attraction to Brock Vond, Frenesi becomes a double agent and is forced to spend much of her life until the present day in witness protection. Her disappearance, a result of Reagan-era cutbacks to such programs, leads to Vond’s resurfacing, along with another ex-agent, Hector Zuñiga, who appears to have escaped from a Tubal detox centre, and is intent on enlisting Zoyd’s aid in finding his ex, so that she can star in a film he believes he is producing. Zoyd’s ‘speciality’ is transfenestration, or jumping through closed windows, shattering the glass. After his latest jump, Zoyd watches a collection of highlights of his previous attempts: “at each step into the past the color and other production values getting worse, and after that a panel including a physics professor, a psychiatrist, and a track-and-field coach live and remote from the Olympics down in L.A. discussing the evolution over the years of Zoyd’s technique”. Thus, early on in the novel, Zoyd witnesses the transference of his own personal experience, albeit caught in the act of fulfilling a deal he had made with the Feds, to the world of the Tube.

Vond and Zuñiga aside, the real villain of Vineland is the Tube (always written with a capital T). Pynchon expresses the fall from radical sixties idealism by contrasting the idealistic notion of the filmic image held by the members of 24fps, with the ubiquity and hypnotic power of the Tube by the time of the mid-80s. The members of 24fps believed that: “When power corrupts, it keeps a log of its progress, written into that most sensitive memory device, the human face. What viewer could believe in the war, the system, the countless lies about American freedom, looking into these mugshots bought and sold?”

Later in the book, Prairie’s punk rocker boyfriend, Isaiah Two Four puts the argument in very stark terms: “Whole problem ‘th you folks’s generation… is you believed in your Revolution, put your lives right out there for it – but you sure didn’t understand much about the Tube. Minute the Tube got hold of you folks that was it, the whole alternative America, el deado meato, just like th’ Indians, sold it all to your real enemies, and even in 1970s dollars – it was way too cheap”.

Thanatoids, essentially the lingering spirits of the dead, spend “at least part of every waking hour with an eye on the Tube”, to the extent that a sitcom about Thanatoids would just be “scenes of Thanatoids watchin’ the Tube.” These were statements applicable to the mid-eighties, when a third-rate movie actor was president of the United States, but if we want to sound out their accuracy against how far further we have come down that road, the following comment made about Donald Trump by self-confessed political dirty trickster, Roger Stone (in the Netflix documentary about him), is chilling in its brazenness:

“Think of the way he looked in that show [The Apprentice]. High backed chair, perfectly lit, great make-up, great hair. Making decisions. Running the show. He looks presidential. Do you think voters, non-sophisticates, make a difference between entertainment and politics?”

Pynchon always had an interest in blurring the boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, and there are numerous occasions, when reading Against The Day, for example, when the reader ponders if the author might actually have spent quite a few of those years MIA from the literary scene, at home smoking marijuana and watching the Tube himself. The numerous references to Star Trek for example, or the appearance of a suspiciously familiar character in ATD named Al Mar-Fuad, who dresses in English hunting tweeds and a deerstalker cap, while brandishing a shotgun and mispronouncing the letter r.

One of Vineland’s running jokes is the fictitious evening movie, often poking fun at such collisions of high and low culture, like: “Pee-wee Herman in The Robert Musil Story.” From his appearance on The Simpsons (with a paper bag with a question mark on it over his head), to his writing of liner notes for albums such as Lotion’s Nobody’s Cool, Pynchon surely always considered himself a part of popular culture. That he offers no clear way out of the predicament he has identified, even in the most overtly political of his novels, is unsurprising, given his modus operandi of describing characters caught up in processes outside of their understanding.

One of the very few ‘serious cultural references’ comes in the form of the following quote from William James’ The Varieties Of Religious Experience:

“Secret retributions are always restoring the level, when disturbed, of the divine justice. It is impossible to tilt the beam. All the tyrants and proprietors and monopolists of the world in vain set their shoulders to heave the bar.”

This is essentially Transcendentalism, a 19th-century American philosophical position that upholds a belief in the inherent goodness of people and nature, whilst casting suspicion on society and its institutions as corrupters of the purity of the individual – a position that shares similarities with anarchism. Pynchon has sometimes been characterised as a libertarian, due to his anti-government stance. The libertarian’s belief in rugged individualism is often criticised as forcing people into an ‘atomistic’ existence, apart from communal institutions and activities. Given that Pynchon’s foremost response to the tyrannical and unjust control of a force that attempts to govern, is the spinning of alternative stories and myths of counterculture cooperations to counteract a coerced grand narrative, this doesn’t ring true. Pynchon’s characters, both the good and the bad, are not in control of their destinies. Even Vineland’s villainous Brock Vond is represented as particular psychological type, subject to his own, (to him) inexplicable inner demons:

“In dreams he could not control, in which lucid intervention was impossible, dreams that couldn’t be denatured by drugs or alcohol, he was visited by his uneasy anima in a number of guises, notably as the Madwoman in the Attic”.

If Vineland can be seen as a novel of the digital age (“It would all be done with keys on alphanumeric keyboards that stood for weightless, invisible chains of electronic presence or absence”), Stone Junction is a stubbornly analogue affair that harks back to more principled, if not particularly less complicated times. In his introduction to the book, Pynchon notes: “You will notice in Stone Junction… a constant celebration of those areas of life that tend to remain cash propelled and thus mostly beyond the reach of the digital. It may be nearly the only example of a consciously analogue Novel.”

Describing the book as “a sort of magician’s Bildungsroman”, it’s not difficult to see the appeal that Stone Junction would have had for Pynchon. Orphaned in childhood, Daniel Pearse is apprenticed to a series of teachers who belong to an organisation known as AMO – the Alliance of Magicians and Outlaws. The skills passed on to Daniel by his unorthodox teachers include meditation, safecracking, gambling, a highly advanced version of the art of disguise and eventually, a method of becoming literally invisible.

As Pynchon notes in his introduction, magic for Jim Dodge is not simply a method of solving plot difficulties, but in fact “hard and honorable work… [that] cannot be deployed at whim, nor without consequences.” One of the novel’s greatest achievements is that it presents the wild arc of its unlikely story in such a fashion that its themes feel familiar, yet when you try and think of other tales that cover similar ground, it’s hard to come up with anything that is at all comparable. Secret societies are hardly uncommon in literature or film, but stories about benevolent secret societies are almost as rare as tales of utopias that aren’t really dystopias. Yet plenty of analogous ground to Dodge’s novel does appear throughout Pynchon’s work. Against The Day has both the “Chums of Chance” (the ballooning boy heroes reminiscent of 19th century boys’ fiction) and the “True Worshippers of the Ineffable Tetractys – or T.W.I.T.” – a mystical society along the lines of Madam Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society or the Order of the Golden Dawn.

A strong anti-establishment sentiment runs throughout Stone Junction. Daniel’s mother, Annalee, breaks the jaw of the head nun at Greenfield Home for Girls, when she tells her she won’t be able to keep her baby. Annalee is killed as a consequence of her involvement in a plot by her lover, metallurgist and alchemist Shamus Malloy, to steal some plutonium. Shamus is perhaps misguided but he is nevertheless driven by a virtuous impulse – the desire to bring about “the dismantling of all nuclear facilities in the country.”

The villains and anti-heroes of Stone Junction are less ambiguous than Vineland’s, yet Dodge’s novel is also more sophisticated than it appears on the surface. Daniel’s second teacher, Mott Stocker, is a six foot eight biker outlaw with a penchant for mouth-numbingly hot chilli, psychedelic drugs, and a strong dislike of Benjamin Franklin. Stocker gleefully burns a hundred dollar bill with Franklin’s image on it, and would happily incinerate more were it not for the other financial interests involved in the deal (recalling the K Foundation’s Burn A Million Quid). Stocker is certainly the rugged individualistic type, yet in contrast to the novel’s less morally appealing characters, it is clear that he works cooperatively within the loosely organised AMO, and that the organisation differentiates itself from the black and white concept of ‘outlaw’ coopted by the the American right.

When discussing the potential to make more money on the deal, Low-Riding Eddie states: “We got a good buy, and you know the rule: Can’t tack on more than a hundred a pound if the Alliance fronts it… Cools the greed.” Stocker, like many of his AMO associates, is an anarchist and a force for chaotic good. As such, he seems cut from an entirely different cloth than the members of the current ‘Bikers For Trump’ movement.

The villain of Stone Junction is Gurry Debritto, an independent, ex-CIA, assassin who killed his first man when he was only 12-years-old. Debritto is a genuinely nasty piece of work, a racist and sexist sadist. He is both an opposite to Daniel, and an interesting contrast to Brock Vond. Although Debritto appears less conflicted by his own inner psychological mechanisms than Vond, he shares a similarly uneasy relationship with his anima to Vineland’s villain, and the end he ultimately meets is closely tied to this aspect of his inner self. The AMO has a strong code governing fatal sanctions against combative individuals: “Ravens are the only adepts that AMO allows to kill other human beings, and they can only use their imagination as a weapon.” Ravens are a class of AMO operative that operate as “Agents of exchange and restitution”. The final event in Gurry Debritto’s story arc makes good use of the notion of the more powerful psychedelic drugs being a kind of litmus paper for the soul – delivering heaven or hell depending on the relationship of the subject to their own conscience.

As the novel progresses, its plot becomes considerably wilder, entering realms of fantasy that may be difficult to entertain for readers more inclined towards literary realism. Unusually for a novel deploying such fantastical tropes as invisibility and huge, perfect diamonds of possibly extra-terrestrial origin, Dodge’s purpose remains clear throughout. In one of the “AMO Mobile Radio” segments that fit in between chapters of the book, the DJ relates the story of ‘The Snake’, concluding: “True story, folks. I dedicate it to all of you realists as a reminder that some gestures transcend failure. I buried the snake in the planter box, fuel for the flowers.”

The DJ’s words find Jennifer Raine, a troubled young woman who eventually escapes the asylum in which she is held. Raine has an imaginary daughter and a lightning shaped scar at the base of her spine, neither of which anyone but herself and Daniel (when they finally meet) can perceive. The appearance of Raine as a character initially seems incongruous. Then it occurs just how clever Dodge is being by incorporating her character as an anima (and lover) for Daniel. The ‘Madwoman in the attic’ (as in Brock Vond’s dream) derives from Charlotte Bronte’s Bertha Rochester in Jane Eyre, and remains a potent image of how insanity was ‘treated’ in the nineteenth century.

That macho characters such as Brock Vond or Gurry Debritto should fear their own inner female side certainly rings true, yet there is still something almost lazy about the ‘madwoman’s’ easy deployment. By including an anima archetype who is welcomed by, and who participates in a kind of mutual healing with, the book’s protagonist, Dodge’s use of the ‘madwoman’ metaphor avoids obvious cliche and bravely attempts a neat resolution, thematically speaking. Even the question of what the diamond that Volta, the leader of the AMO, tasks Daniel with stealing, actually is, is answerable given some thought. The diamond, too perfect to have developed naturally on earth and also beyond scientific manufacture, appears to represent the possibility of an alien intelligence superior to our own – an answer to that ultimate question of whether or not we are alone in the universe.

Whilst Pynchon’s writing style is considerably more idiosyncratic and sophisticated than Dodge’s,

Stone Junction, is in many ways a more enjoyable and pulse quickening read than Vineland. Taken together though, the two novels offer a fascinating set of philosophical ideas with which to consider the 60s era central to them both. It’s tempting to think of the “alchemical pot-boiler”, Stone Junction, as a kind of wild evening movie that Vineland’s characters could have sat around watching, and which in some metaphorical sense, might have provided some useful thematic materials for understanding the nature of their own predicament. It is perhaps interesting to note that the only time televisions are referenced in Stone Junction is when the AMO pilot, Red Freddie, suggests that: “the highest revolutionary act available to middle-class people in the 1980s would be piling their television sets in the middle of the street and setting them ablaze with their front doors.”