Photo by Marie Remy

Tijinder Singh has a sparkle in his eye as he leads tQ up the spiral staircase at The Wellcome Collection, Euston Road’s science and medicine library and museum. As we make our way to the busy café on the second floor, he says with a conspiratorial smile: “They do tea with cream here.”

Singh and fellow bandmate Ben Ayres are here to discuss England Is A Garden, Cornershop’s ninth album, and their first in five years since an easy listening reimagining of their debut long player, Hold On It Hurts. The pair share the relaxed air of long-time friends who go way back to a shared house in Preston, where they met while studying at the city’s polytechnic in the late 1980s.

England Is A Garden has been some seven years in the making partly due to health problems that left Singh “worn out and debilitated” and suffering dizzy spells, but he doesn’t dwell upon them. He’s puzzled that “people are saying it’s been a long time” since Judy Sucks A Lemon, Cornershop’s last full-blown album from 2009, pointing out they made the Double ‘O’ Groove Of album with Bubbley Kaur in 2011 and Urban Turban, a compilation LP with guest singers the following year, followed by Hold On It’s Easy in 2015. He and Ayres have “kept busy” with their label, Ample Play, and there has been “a few sprinkles of singles and we’ve certainly put out other groups as well”.

“Also,” he says, “with this album we knew that we had to wait for a better time for it to be received. A couple of years ago this wouldn’t have been the case and then even when it was finished it took a while to get it mastered and to get it into production because things change.”

The band have always worked at their own pace over the course of the last 30 years. “Unfortunately, that has been a very fast pace, if you think of the first three albums, 94, 95, 96-97,” Singh says. “The other one was done in 2001 and that was out in 2002, but before Handcream there was the Clinton album in 99 as well. We’ve always gone at our own pace. If we could go any faster we would but no-one’s known what the albums are going to be until we get to the studio.”

As is common with Cornershop albums, there was no definable starting point for England Is A Garden. “We did a hell of a lot of songs, probably about four albums’ worth,” Singh explains. “In the end we had to pick 20 that would make a good album and B-sides and just stick to that.”

“It was an effective policy, though, because we started all these ideas and then we had to think which ones are the most interesting or work the best,” Ayres says.

“Well, it was after seven years,” Singh smiles.

The album’s inviting blend of sounds, from the Velvet Underground and T.Rex to funk, psychedelia and Punjabi folk, will be familiar to long-time fans, but its lyrical bite is entirely contemporary. While Singh concedes he and Ayres are keen record collectors and “do like certain groups”, he is wary of being tagged as nostalgic. “People can’t pinpoint us,” he says. “If you’ve got people saying, ‘They sound like the Velvets’ and then other people saying, ‘They sound like the Stones’, they wouldn’t put those two together… I think the interesting zone is in the middle, when you have moved away from that initial thought. That’s always been the way that we’ve tackled songs. If people can live with them then they’ll get more out of them because there’s more in there. With this album, because we had the time to put a lot of different things in it, because we were moving from one studio to another, because we were working with different people, there are little bits in there that have just been left that you wouldn’t notice at all if you didn’t think about them. You might notice after five listens or you might not hear them at all.”

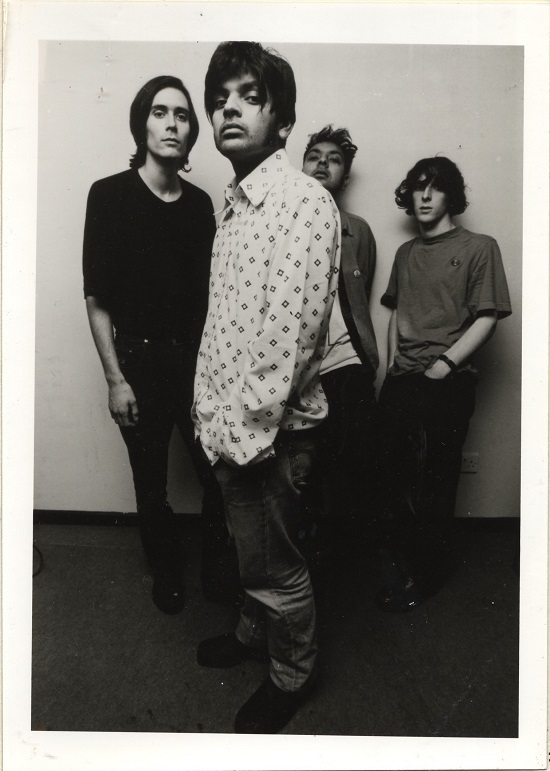

Cornershop’s very first press picture, 1992

“When a lot of people learn how to play or they start a band, the first thing they tackle is cover versions,” says Ayres. “We never did that, we literally couldn’t play them, so making up our own songs was what we had to do. I think that’s an interesting aspect, that’s defined us a bit.”

“We never wanted to learn our instruments either,” says Singh. “You would sound like someone else if you learned your instrument. If you’re free to do whatever you like it might take a long time, as is evident.”

Although not an album about Brexit per se, the referendum result and the ensuing three-and-a-half years of political wrangling formed the backdrop to England Is A Garden. As committed Remainers, Singh and Ayres both wonder where the country is heading. “No-one knows where they’re going but as Curtis [Mayfield] said, we’re probably all going to hell, that’s for damn sure,” Singh says.

“Actually, that’s another reason why the album took so long. I actually spent three-and-a-half years before the referendum campaigning against it and it consumes you. We were always of the opinion that it’s such a monumental change to life, regardless of the music industry.

“We were talking this week about the Priti Patel thing,” he continues. “We did a letter and we asked people to sign and they couldn’t give a shit, the musicians couldn’t give a shit, but in a way that’s a microcosm for the country. Musicians are divided people; they’ve got to get on with music. You’ve got to remember that we said we weren’t musicians,” he smiles. “They’re sporadic so therefore they let people get on with whatever they want to do, and they miss a trick, and I think that’s what the country’s done as well, they’ve missed a trick, they’ve been bought. Today it’s come out that there’s a lot of heavy backers who pumped money in and bought the ‘Red Wall’ so the Tories won. It’s really obvious but that’s what’s happened.”

The album’s opening track, ‘St Marie Under Cannon’, considers the effects of colonialism. “It’s from looking back at Enoch Powell’s time forward to where we are now with Brexit,” Singh says. The pair had wanted to release another contentious track, ‘Everywhere That Wog Army Roam’, as a single but were convinced “it might be a bit too fruity for radio” so changed their minds. “Actually if you look at the lyrics to ‘St Marie Under Cannon’, they’re probably more offensive than ‘Wog Army Roam’,” Singh says. “It’s having a go at colonialism, it’s not saying it’s a great thing at all. It’s spread over centuries, not a few decades, it’s not just Rastas in the 70s, we’ve had quite a long time of oppression.”

“I think it’s a great shame that the history of the Empire, good and bad, isn’t taught more in detail in schools,” Ayres says. “It seems to be totally ignored. A proper understanding of the past would stop people being so ignorant about why certain communities living in England, who have served England, fought for England in the past. It’s such a weird, distorted view that a lot of people have. History should teach us.”

Cornershop have used the ‘w’ word – an acronym for ‘Western Oriental Gentleman’ – a number of times in songs, turning it back upon those who would use the term as a racist insult. “We used it in the Woman’s Got To Have It album, it was just called ‘Wog’. Then ‘Wogs Will Walk’ and ‘Wog Trigonometry’, and there’s quite a few [uses] in the cupboard that we haven’t brought out yet,” Singh says. “Again, it’s history and even though it’s offensive to some, it seems very offensive if you break the acronym down into words. It’s as soft as anything. But I think it’s a word that deserves to remain in use, to remind us what Empire was about. Again, it’s one word that goes back centuries, not just decades.”

Elsewhere, the influence of Marc Bolan on tracks such as ‘I’m A Wooden Soldier’ has apparently happened more by osmosis than intent. Singh says he and Ayres “spent six months just listening to Bolan” when they lived in Preston in the 1980s “so there’s going to be elements of that coming out”, however, he says: “Anyone who’s tried to do Marc Bolan, even cover versions, has fallen flat, so one could never be so bold as to do it straight.”

“Any similarities are inadvertent, but we are huge fans of his work,” Ayres adds. “He was an absolute genius. He was actually born very near to where Tjinder is now living.”

“His leather Slider hat was in our local library for a while until it got pillaged,” Singh notes with another smile.

Ayres says his girlfriend Kate first got him into T.Rex when he was listening to the likes of The Byrds. “I think it was from her older sister, Fiona, who was one of the very early punks that grew up in the West Country,” he continues. “Kate used to play Marc Bolan all the time. I hadn’t known it until I met her, and I was just bowled over by the quality, literally everything was brilliant, I couldn’t believe it. We particularly liked the later period Bolan, the Futuristic Dragon era.”

Singh admires the “formidable attitude” in the production and wonders, “How can one person do that many memorable songs?” Ayres recalls: “Many years ago we went to a sausage restaurant with John Peel and one of the main things I wanted to ask him was about his friendship with Marc Bolan. It was a bit of a sore subject in a way because they fell out about one his tracks that John didn’t play, but he told us a lovely story about how one afternoon they spent an afternoon in a boat on a lake just chatting away.”

“It was a vegetarian sausage restaurant, which was a new-fangled thing in those days,” Singh hastens to add.

Growing up in Wolverhampton in the 1970s and 80s as the son of Sikh immigrants, Singh says, was “pressure every day”. “You walked out hoping there was no other white people about, it would make my life a lot easier, that’s how it was, you would get hassle,” he says. “A couple of chaps who lived a few doors from us they were quite hard. They would give us a bit of shit every now and then but luckily they would save us from quite a few scrapes as well.”

This was an era when Enoch Powell was MP for Wolverhampton South West. “People went to the factories and that’s what they had in their heads,” Singh says. “They were working with people like my mum and it was tense. Then you could see it getting less tense, in the 90s it was great for a while, then it got shit again and we are back to where we were.”

The first music he listened to was Punjabi folk and devotional music. “Indie guitar music was what my middle brother [Avtar] who was in the band to start with was more into. When Ben and I met I was more into reggae.”

The guitar influence would come from Ayres, who was born in Canada to British parents and moved to England when he was nine. “The first record that I remember asking to get was a Canadian heavy metal band called The Stampeders, which me and my little friend Garth, who had a caveman hairdo, liked,” he recalls. “We were young boys who just wanted to rock.” He would move on to The Beatles and 80s indie guitar bands.

The pair met when they were sharing a house with ten other freshers at Lancashire Polytechnic in Preston. “We saw each other as I was unloading the car,” Ayres remembers. “We said ‘hello, fancy going out for a drink?’ Six weeks later we stopped going out for a drink every night.”

“In the first year we knew each other and we talked about different things but it was not until the second year when were in a different house with just the four of us that was when we started doing music,” Singh says.

“You had to keep busy because there was very little heating,” Ayres says. “Of the four people in that house we quickly realised that we got along best. We both liked music so we would go and see bands play in Preston. Eventually after seeing a few bands that could barely play we thought we should have a go at it. We thought we’d get a tape recorder and see what it sounded like.” One early song featured a single chord. “It was quite linear,” Ayres quips.

Together they would “make quite a few albums just on cassette” at home, Singh recalls. “We would not let anyone hear them, certainly not our mothers,” he adds. “It was because we lived in a different world from other people, and it was a nice world to live in, where we shared these tapes between three people.”

Ayres would design artwork for the cassettes while his bandmate developed an interest in tape technology, “switching these tapes backwards and overdubbing things, which initially to me seemed liked magic."

“I learned about recording tapes mainly through Asian devotional stuff in the temple,” Singh says.

“I think that’s what gave us the bug of being creative and made us think we could actually realise ideas and try things,” Ayres says.

Naming the band General Havoc, the pair recruited a drummer, David Chambers. “David was a DJ at the Rumble Club and then it became Raiders,” Singh says. “When he heard our music he was the only person who thought, ‘This is great’.

“He did a fanzine as well and he passed it on to other people in fanzines and got reviews for it and we thought, ‘This is quite easy to do.’ So we asked him to play drums which he had never done before but he learnt. Then I asked my brother [Avtar] to play guitar, he was as bad as us so we had four people that couldn’t really play their instruments and we thought, ‘This is how you do it’.”

“Initially David just had a stand-up drum and a lawnmower head instead of cymbal,” Ayres remembers. “It worked.”

Their music would take a more serious turn when Singh was elected the student union entertainments officer. “I got three votes of no confidence in the first two weeks and lots of shit for a whole year, and I had to battle through that,” he says, recalling “physical violence and intimidation”. “People did not like a black chap coming in and doing not just a role but the ents officer role, which is seen as a great favour to other people, but my campaign was tight and I talked to people and they agreed with what I said in terms of the resources and the lack of them, and I got in very easily.”

The experiences changed his outlook, he says, “from just doing music to being more political and honing what we were trying to say”. Instead of pursuing a graduate apprenticeship in IT, he concentrated his efforts on the band. Their first gig was at O’Jays in Leicester, where Singh’s brother and sister were living. “We couldn’t shit on our own turf,” he jokes.

“We lost half our gear,” Ayres recalls. “We ended in a hail of feedback. It had been a pretty tense atmosphere in there during the set and at the end we legged it outside to get some air. By the time we went back inside half the gear had disappeared.”

They were signed in late 1992 by Wiiija Records, whose boss Gary Walker saw them perform at Harlow Square. “When we left the stage we were commiserating with each other as we slowly came off,” Singh says. “It was not a good gig from what we thought and the stage was trashed, and then young kids started coming up to us saying, ‘That was fucking great’.”

The label was then associated with the Riot Grrrl movement via bands such as Huggy Bear and Blood Sausage. “They came to gigs but they also stood in in interviews and they sort of vetted us,” Singh says. “They wanted to hear what we had to say and we found we had a lot in common in terms of being motivated to speak out about stuff,” Ayres adds. “We had similar attitudes creatively with music as well.”

“It was very vibrant, every day was different, and then I started working for Wiiija in Portobello, in the basement, and Ben was working for a record manufacturing company,” Singh says.

The band made a splash when they accused Morrissey of racism and burnt a picture of the singer outside the offices of EMI for an article in Melody Maker. Twenty-seven years later, Singh reflects: “Now he wears T-shirts and you can tell that the bloke is whatever he is, but then it was a case of that imagery plus those T-shirts plus comments, he [was] talking about vegetarianism and [hadn’t] said a jot about racism. When you put it together you had to think about it, rather than just go for it, or else the press would have got you. I know people said it was a press thing; no, the press would’ve got us if we hadn’t got our shit together. We’re very happy with that, we’re very proud of it.”

After their first album, Hold On It Hurts, the band signed a US deal with David Byrne’s label Luaka Bop. “His label office was in the downstairs of his house,” Ayres says. “We recorded with [Allen] Ginsberg there, we walked to Ginsberg’s flat with David.”

When Chambers left the band in 1994, he was replaced by Nick Simms, with whom they would go on to make their breakthrough single ‘6am Jullandar Shere’ and album Woman’s Gotta Have It. The band’s greatest commercial success would come in 1997 with their acclaimed album When I Was Born For The 7th Time, whose lead track ‘Brimful Of Asha’ topped John Peel’s Festive 50 poll and became a UK number one the next year when it was remixed by Fatboy Slim.

Singh admits “there’s no two bones” that the single’s ubiquity overshadowed the album itself. “The album was doing very well in America, it was Spin magazine’s album of the year and it had set us up for great things. When [the Fatboy Slim remix came out] it took a lot of the shine off the rest of it, but in terms of what it was when we first heard it we loved it, we still love it now, we think it just works. We love both versions. It’s been a two-edged sword. We did say keep the sword hand free, and we probably needed to with the next song.”

The moment of pop stardom would have a lasting effect on their lives. “Looking back, you can’t say that you weren’t affected,” Singh says. “People could see who I was whereas Ben was a little more in the dark.”

“You’d still have strange moments, though, where you’re treated differently by people or there were people hanging round that you didn’t know or you wonder why,” Ayres says. “It’s a strange thing. I didn’t like it.”

“It’s weird to walk into a room and everyone knows about you, but you don’t know them from Adam,” Singh says.

“One of my memories is that we went to Japan to do a load of press and one day we were taken to the label that was putting our music out. We were ushered into this room and we were all over the place having flown through lots of time zones. There was a massive open table with about 150 people in suits and two empty chairs and we were asked to do a presentation of what our album was about.”

“They were clapping and playing the album as we were coming in,” Singh remembers. “And they asked us to talk even though we could hardly string a few sentences together, but it was really good. The Japanese are lovely people. It’s a different culture and that’s how they expect you to do things, so you do it.”

“I suppose that’s the sort of thing Billy Ocean has to do all the time,” Ayres notes wryly. “When you have a number one and you’re in the news, we were in the tabloids at times, but we just saw [celebrity] for what it was, growing up as music fans.”

“Also, we were a bit older as well,” Singh says. “To get to that level was nice but we were always in charge of ourselves, and it was scary at times. When we got to America it was a bit more difficult to keep the Class A’s out of the picture.”

As well as the disco-funk side project Clinton, Cornershop would go on to make one more album for Wiiija, Handcream For A Generation, in 2002. The album featured a guest appearance by Noel Gallagher, whose band Oasis Cornershop had toured with, and was well reviewed, yet it left Singh and Ayres creatively spent. “We worked really hard and it wasn’t anything less than When I Was Born For The 7th Time was,” Singh says. “That was when the burnout from all the mass of activity really hit us,” Ayres says. “We were also very disappointed with how the record was worked in certain areas. It was a hard time.”

They decided to found their own label, Ample Play, which continues to this day. “We don’t mind people cracking the whip,” Ayres says, “but I think the greater motivation for us doing our own label was people like Curtis Mayfield, having control of their own catalogue and their own label.” They might have given up touring at Singh’s behest – though he jokes about the rest of the band going out on the road with stand-in singers – both have high hopes for England Is A Garden. Singh also talks of completing a documentary film on the music business that he began in the early 2000s.

“We’re right down to an album now which shows we haven’t stepped off the gas at all,” he says. “We’ve always had something to prove. We could’ve given up like any 90s band but we didn’t. It’s not just albums but singles as well. Everything we’ve done has seemed to put us back at square one. I think part of that is to do with the variety of music that we’ve made and partly we just find it hard to do this. We’re not as clearly defined as other bands are.”

“Although it’s a bit unfortunate for us in a way that is the case, I think that does push us to give everything when we’re making records, it pushes us to give everything when we make each individual song,” Ayres says. “We’ve never felt relaxed enough to sit on our laurels or just go through the motions. And that would probably kill Cornershop anyway.”

England Is A Garden is out on 6 March