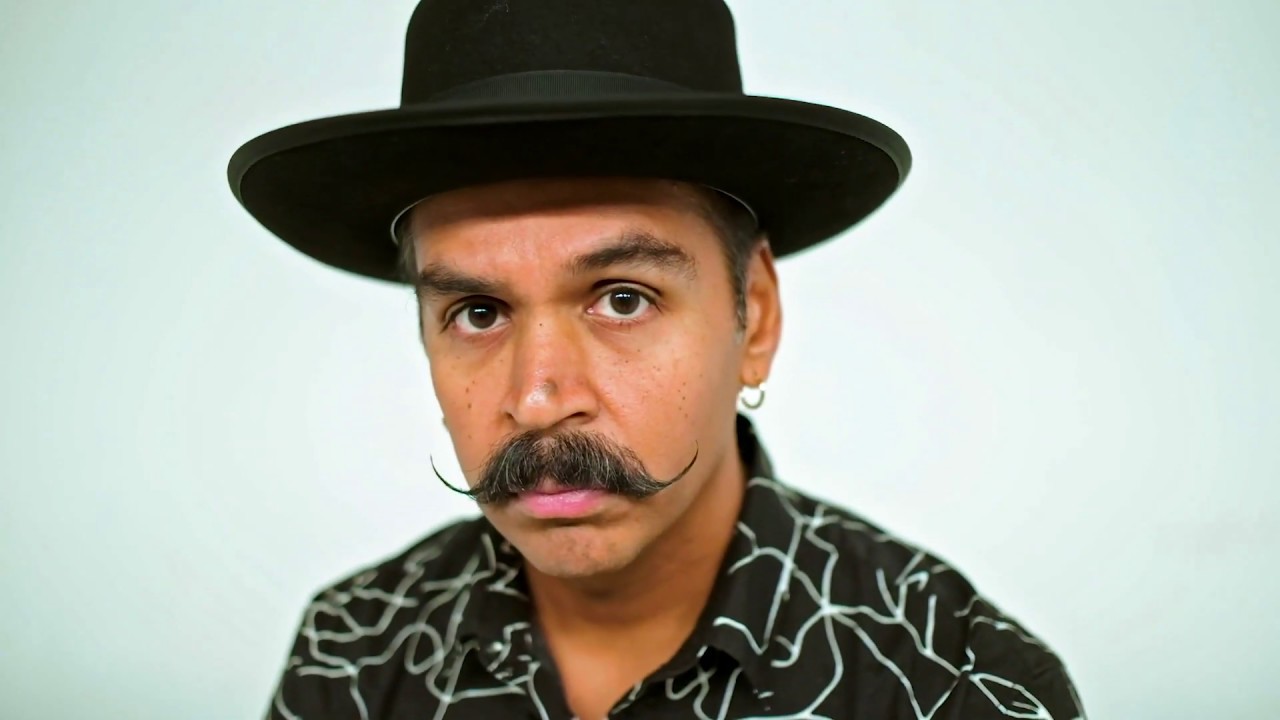

Sunny Jain portraits by Ebru Yildiz

Try counting the number of musical bands, projects and organisations Sunny Jain has been a part of and you’ll quickly lose track. The Indian-American drummer has been a figure in New York’s jazz and so-called world music scene since around the start of the millennium, and has been ensconced in music for his entire life. While he has certainly never ceased being musically active, his new album Wild Wild East is the first under his own name for ten years and, although it features a range of musical collaborators, it’s an album that could only have been attributed to Sunny Jain.

“I’ve been trying to do it since 2014 or 2015, but I was unable to find the time to sit down and conceptualise it, to think about the sound and the meaning behind it,” he says on the phone from his Brooklyn home. “I have to write from an emotional place. It has to be derived from some kind of narrative.”

Eventually a few coinciding events provided the decisive spark that lit the fire under his behind and set him firmly on the path to creating Wild Wild East: Trump’s election, an approach from Smithsonian Folkways to be the first in a new series of releases from Asian-American musicians, and the sight of a giant cowboy representing “America” in Dubai’s Global Village. “All these things were swirling in my head around immigration and representation of an American – what it means to be an ‘American’, what it means to be an ‘immigrant’ and what it means to be a ‘cowboy’.”

The resulting album has all of these ideas creatively enfolded into its 51-minute run time, and the title Wild Wild East sews them together. On the visceral surface level, the title is a comment about the current seat of power on the East of the USA: “It’s crazy how New York and DC are now stripping the constitutional law and people’s rights – and where are the politicians standing up to this injustice?”

Secondly, it’s playing on the idea of ‘Wild West’ and the archetypes of Cowboys and Indians: “When I was young and I heard about the game of Cowboys and Indians, I thought they were talking about my type of Indian. I even remember in elementary school I had a native indigenous friend and I remember asking him, ‘Where in India are you from?’”

Further to that, Sunny believes that the classic American ideal of the ‘cowboy’ needs updating: “I think about refugees and the angst they have to go through, their experience leaving behind their homeland and going somewhere foreign to start a new life, whether it be for opportunity or through necessity, that takes an amazing amount of courage. I started thinking: the immigrant is really the current day cowboy, but we never see faces of immigrants in an American sensibility or in the cowboy.”

This tale of immigration is the bedrock of Wild Wild East, which is actually, under all those other ideas, a deeply personal album for Sunny. It has a loose narrative around his parents’ struggle with being forced out of their native home upon the 1947 partition of India, and their decision to emigrate to New York – leaving everything and everyone they knew behind.

Having traversed continents and genres continually in his career as a musician, Sunny was able to call upon many trusted and divergent collaborators to help him bring this passion project into reality. Some, like guitarist Grey McMurray and sousaphone player Kenny Bentley, he’s known for over a decade, whereas others, like tenor sax player Pawan Benjamin, he’s only been working with for a couple of years.

Along with Jain on drums, these three formed the core of the band that created the genre-crossing soundscapes of Wild Wild East, which incorporates everything from jazz rhythms to shoegaze guitars to Middle Eastern brass and beyond. “It was very collaborative; I talked about the ideas of what I wanted the songs to evoke and their meanings. They may not have understood what this old Indian village means in my family lineage, but I wanted to tell them the story and see what they did with it. I got these players because I like what they do and I felt good that they were going to bring the music to life.”

There is undoubtedly a cinematic quality to the arrangements on Wild Wild East, so it’s no surprise that films were a big part of his artistic upbringing. The imprint of Ennio Morricone and soundtracks of spaghetti westerns inform the expansive instrumental songs, but Bollywood films also play a part. “On weekends, by nine or ten, the adults would put the kids in one room and turn on a Bollywood movie, which is about three hours, and they would go play poker in the other room,” Sunny recalls. “I saw everything, all the hit films of Amitabh Bachchan, so a lot of that imagery is still ingrained in my head.”

On several of the tracks these players are joined by vocalists representing an impressive array of styles. ‘Red, Brown, Black’, the only song with English vocals, is helmed by Muslim Asian-American rapper Haseeb, who stylishly approaches the broadness of the album’s topics, succinctly and emphatically pulling them together. “I grew up speaking English, that’s my first language, and I just wanted to have something relating to identity that was very direct and hit the concept on the nose, and Haseeb did that.”

The rest of the vocals on the record are in a range of Indo-Aryan languages, including Hindi, Punjabi and Gujarati, but Sunny’s chosen collaborators ensure this is not a barrier to entry. Female vocalist Ganavya brings her powerfully soaring voice to a few songs, including new takes on Bollywood favourites ‘Hai Apna Dil to Aawara’ and ‘Aye Mere Dil Kahin Aur Chal’. Then there is Aditya Prakash, who brings sombre strength to the ‘Baaghi’, a song of rebellion about Kartar Singh, an 18-year-old martyr who was executed in 1915 for his actions with the revolutionary Ghadar Party.

The performances of both singers are startlingly bold, ensuring none of the passion or emphasis is lost, even for those who won’t understand the words. “Both of them showed that they’re top calibre vocalists,” Sunny says. “They did all the prep beforehand and then they just came in and – bam! – nailed it. It was incredible. They took it to places I wasn’t expecting, it elevated everything.”

There is a spirit that hovers over Wild Wild East: that of Sunny’s father, Shri Jain, who passed away in November. This drove Sunny to even greater lengths in exploring his family history on the record. This is beautifully displayed in the liner notes, which feature an essay by historian Vivek Bald woven around snaps of Sunny’s parents in their youth and historical photos of Indians in their native land and in America. “I pulled all the images and Folkways helped in securing the rights for them, which was truly amazing because some of them were very hard to get,” Sunny excitedly explains. “I said I really needed this picture of South Asians on top of the Sialkot train during partition, this is important. These are images that my dad would talk about and I need this here.”

The memory of Shri is deep set into the music as well, and his own bulbul tarang – an instrument also known as the ‘Indian banjo’ – is played in the song ‘Remembrance’. This is followed by ‘Aye Mere Dil Kahin Aur Chal’, which comes from the Hindi film Daag and is a song he remembers his father playing in the house when he and his siblings were children. “At least once a week he would take out his bulbul tarang and he would only play a few songs on it. It felt like he was searching for the notes and trying to remember the melody, singing while trying to find the notes, because he wasn’t a musician, just a music enthusiast,” he remembers fondly.

‘Hai Apna Dil to Aawara’ was another of his father’s favourite songs to play, and also makes an appearance on Wild Wild East. “He would be there singing it and trying to dance with my mom,” Jain laughs. “My brother, my sister and I would joke with him like ‘Oh my god, you’re playing that song again, can’t you learn other songs?’, but now I look back on it and they’re my childhood lullabies.”

Having grown up in a house full of music and expression, he is ensuring that his young twin daughters are experiencing the same thing. “They’re definitely get a lot of music at home, I’m constantly playing different kinds of music, and in the neighbourhood we live in there’s a lovely little school where their music teacher is an old downtown New York City avant garde sax player, which is awesome.” They’re also fans of their father’s work: “They ask for it regularly, they’re literally my biggest little fans. I’ve had to ban my music when I’m home because they’ll constantly put it on.”

Perhaps, then, Wild Wild East will be the first in a generational series exploring the history of the Jain lineage. One can only hope.

Sunny Jain’s Wild Wild East is out now on Smithsonian Folkways Recordings