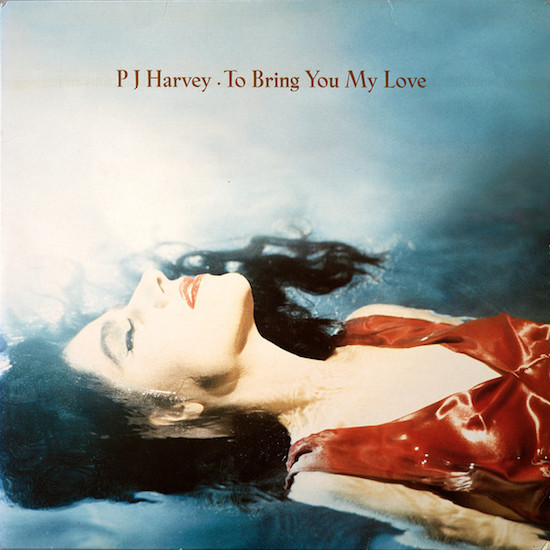

Whenever people asked why the farmer’s pugilistic, punky daughter had reinvented herself as a monstrous vamp, PJ Harvey had an easy answer for them. “I enjoy looking like a tart and thinking like a politician,” she teased iD in 1995, setting out the careful plotting behind an unsettling new persona that had the cracked glamour and sultry poison of a murderous Rita Hayworth (or, as Harvey preferred, “Joan Crawford on acid”). Her corruption of Hollywood legend didn’t stop there. The cover of her new record, To Bring You My Love, could have been a warped parody of the moment everything turns Technicolor in The Wizard Of Oz. Unlike the grotty black-and-white sleeve of 1993’s Rid Of Me, it was saturated in poison-apple colours: Harvey’s blood-red dress and slash of lipstick, her alabaster skin and aquamarine eyeshadow. Even the marbled blue water she floated in had the vivid hue of a fairytale river, in which she might be a drowned Ophelia, or baptised as a born-again femme fatale.

People were often easily shocked by images of Harvey – it had only been three years since NME’s cover featuring her naked back caused much clutching of pearls – but this transition would make anyone double-take. Yet it made sense, too: she’d rung the changes for her third LP, and they went far beyond her lurid makeover. She disbanded the PJ Harvey Trio, her group since 1991, to go solo, and brought in new foils including Bad Seed Mick Harvey and old friend John Parish. Steve Albini, whose raw production contributed to Rid Of Me’s flayed-alive style, was replaced by the more melodically inclined Flood. And while Harvey’s work had always betrayed her love for the blues, it had never had been so dramatically devilish: the sound of some gothic, godforsaken Deep South full of blood and bibles, sinners and victims, love and despair.

You could never deny To Bring You My Love was a huge stylistic shift; not when Harvey’s songs had mutated into something from her hero Howlin’ Wolf’s worst nightmares, and she debuted her famous hot-pink catsuit at that year’s Glastonbury. But 25 years on, the idea that it marked an artistic watershed isn’t quite right, either. Yes, she’d changed how she sounded and looked, but not how she worked. In fact, its stormy sensuality and torrid theatrics only put up in lights what Harvey had always said, even if people seldom listened: she was a storyteller, not a diarist, and an actor as much as a singer.

By 1995, Harvey had spent a depressing amount of time debunking the assumption that her music was autobiographical. Many had figured that the brutal imagery of her 1992 debut, Dry, must have stemmed solely from real-life experience; the truth was that if you’d cut her open, she’d have probably bled greasepaint. It could be violent and disturbing, but she also played for murky laughs by deliberately sending up tired virgin-whore tropes, pivoting from a licentious other woman’s leer on ‘Oh My Lover’ to an ingenue’s clumsy breathlessness on ‘Dress’. And while her nervous breakdown gave Rid Of Me a bleak backstory, that album wasn’t a confessional outpouring either. As Judy Berman’s terrific reappraisal explains, its songs were about performances – the parts people were forced to play, or tried to challenge – as well as being stellar performances themselves. Sometimes Harvey became other characters, like Tarzan’s fed-up other half, or Eve venting her spleen at the serpent. Sometimes she adopted a terrifying alter-ego: her delivery on ‘50 Ft Queenie’ was, she said, inspired by the braggadocio of hip hop, a literally monstrous way of bigging herself up.

Harvey knew she had to throw herself fully into her ideas to pull them off. "If you write words like that and sing it in the wrong way, it’s a complete disaster," she told Rolling Stone. Her voice may have sounded like a force of nature, but focusing on its elemental power sold short her judicious precision, the way she manipulated it to do her bidding. When she told the LA Times her favourite singer was Elvis, they assumed she meant Costello because of their shared sense of musical ambition; she was actually talking about Presley, another artist who, like her, knew exactly how to use their primal talent. “I love his singing, the passion, the depth in his vocals,” she enthused.

But on To Bring You My Love, Harvey is less like either Elvis and more Marlon Brando: an actor with intense, chameleonic charisma, as tough, scary, heartbreaking or unnerving as each role demands, bringing the record’s desperate souls to life with her full-blooded, full-bodied portrayals. “I’ve lain with the devil, cursed God above,” she seethes over the title track’s sinister, serpentine guitar and eerie organ, full of such bitter longing that her voice shakes and trembles and sounds inhuman; when she rasps “I was born in the desert, I’ve been down for years”, she sounds like a hungrier, lustier incarnation of the rough beast from WB Yeats’ The Second Coming. On an album that explores how anyone can be unhinged by the all-consuming craving for sex, love, spiritual salvation and human connection, it’s the perfect transformation: a spurned admirer turned into an unearthly creature, dragging herself across the sand and bringing the apocalsypse with her.

Next, she brings a similarly demonic energy to ‘Meet Ze Monsta’ (which, like several songs, referenced another of Harvey’s idols, Captain Beefheart) and its netherworld stomp of sludgy, grungy riffs – only this time she adopts the tough-talking swagger of a larger-than-life prizefighter, like she’s looking the devil in the eye and refusing to back down from a scrap. “I see it coming at my head,” she taunts in a deep, defiant bark. “I’m not running, I’m not scared.” Then, for the uneasy chug of ‘Working For The Man’, she changes again, turning into a hushed, lonely figure driving down a dark highway in pursuit of love. “God is here being my wheel,” she murmurs, channelling the conviction of a zealot steeling herself for something awful.

Those first three songs alone have the range of a character actor’s showreel: three stories, three protagonists, three entirely different performances. As Harvey explained to the LA Times that year, she’d spent a lot of time honing her craft. “When I was young, I wrote plays,” she said. “And performed all the different characters when my parents’ friends would come over.” She approached records like To Bring You My Love with the same spirit, giving each character their own tale of rejection or ruinous obsession, and their own way of telling it. On the beautiful, bittersweet strum of ‘C’mon Billy’ she’s the personification of anguish, her wounded pleas catching in her throat as she begs her partner to return to their son. And then she spins that vulnerability completely on its head by playing another mother on the edge, only this time with a terrible secret.

‘Down By The Water’ still unfolds with the dramatic tension of a chilling one-woman play, the kind that makes your face blanch and stomach drop. Harvey’s narrator reels you in by hollering for her drowned daughter, although the the grubby, buzzing organ suggests something fouler at hand. Then comes the sucker-punch: the growing dread as you realise what she’s done, the sharp stab of cruel strings, her disturbingly fervid tone as she half-confesses, half-justifies her crime: “I had to lose her, to do her harm!” And when it finally ends, it’s not with a bang but a dreadful whisper: “Little fish, big fish, swimming in the water/ Come back here man, gimme my daughter.” Harvey’s delivery has the creepy cadence of a twisted nursery-rhyme, recited by a person so broken they’ve been driven to madness, or who thinks they can fix everything by chanting an incantation.

There were, Harvey wryly observed, some blinkered people who heard it and really believed she’d committed filicide. As she revealed to Rolling Stone, the reality was less gruesome: she knew how to use her own experiences for emotional fodder like a seasoned thespian, and also found it easy to imagine how other people must feel when they were suffering, too. Her interest in visual mediums like film – ‘50 Ft Queenie’, of course, owed a debt to the 1958 monster movie Attack Of The 50 Foot Woman – added to her work’s cinematic splendour. She wrote ‘Teclo’ after hearing Ennio Morricone’s ‘Teclo’s Death’, from his 1968 Guns For San Sebastián score. Her composition throbs with melodic instrumentation, and Harvey casts herself not as the titular Teclo but one of his mourners. “Just let me ride on his grace for a while,” she croons, summoning the doomy grandeur of someone singing a lonely elegy out in the moonlit plains – a finale worthy of any epic spaghetti western.

Then again, it’s easy to imagine most of these songs thudding out of cinema speakers, especially the rockier, rougher ones (and especially in 1995, when alternative bands were favourites on big-screen soundtracks: The Cure on Judge Dredd, Hole, Belly and more on Tank Girl, Juliette Lewis covering Harvey for Strange Days). The blistering, unholy din of ‘Long Snake Moan’ has the dank aesthetic of an underground action flick, with filthy riffs and blasts of noise that detonate like bombs, while Harvey snarls about drowning, ritual and resurrection like a mythical warrior queen on a power-and-pleasure trip. “It’s my voodoo working!” she crows at the end, as the ground cracks beneath her feet and the walls cave in.

Listening now, it can seem like Harvey would rather play anyone than herself on To Bring You My Love, and its cast of pointedly exaggerated, often abandoned female archetypes must have vexed anyone looking for real-life tidbits. Yet her supposedly autobiographical albums aren’t always much more revealing than the elaborate fantasies. Her 2000 LP Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea was tangibly rooted in her experiences in New York, London and Dorset. That title, though, also hinted at the way personal experience can be romanticised into narrative – at old memories being recast with the same extravagant gloss as Harvey’s lush melodies – and tracks like ‘You Said Something’ are both intimate and elliptical: it dances around a charged conversation between two people, capturing their shared electricity without ever divulging the discussion itself. Her ostensibly truest-to-life work, meanwhile, is 2016’s The Hope Six Demolition Project, on which she documented trips to Kosovo, Afghanistan and Washington but felt curiously absent as a narrator, preferring to report what she saw rather than reflect on how it made her feel.

Harvey’s characters, on the other hand, tend to be far more forthcoming. On ‘Send His Love To Me’, Harvey’s protagonist is ditched by her lover and has to beg Jesus for help. “Left alone in the desert/ This house becomes a hell,” she gasps, battling against its choppy guitar and fraught orchestration. Harvey wasn’t religious herself (although she was fascinated by the mythology), but it didn’t matter; she didn’t need to explain her own beliefs to portray someone with a hopeless thirst for divine intervention. It benefitted her not to: freeing herself from autobiographical shackles meant she could attack ideas without restraint or reticence, and push characters into the extreme places most wouldn’t dare tread.

All of To Bring You My Love’s drama and desperation reaches a crescendo on ‘The Dancer’, on which Harvey plays the tragic, tortured heroine of a great gothic western. Everything about it drips with melodrama – the lavish, Morricone-like arrangements, the flaming, flouncy Spanish guitar, the rich throb of organ – and Harvey’s fire-and-brimstone passion is heightened by her swooping, operatic vocal. “He came dressed in black with a cross bearing my name,” she cries in rapture, though her heaven-sent love is only fleeting and she’s soon back in the depths of despair. For all the opulence, it’s most devastating when Harvey gives up on telling her story, and instead just shrieks and yelps as if doubled-over by grief. To Bring You My Love ends the way it began: another spurned figure undone by desire, their need for something to fill the void so violent it rips an even bigger hole in them.

Because there’s no such thing as a straight throughline in Harvey’s higgledy-piggledy catalogue, only a few swampy fumes survived on 1998’s desolate Is This Desire? (although that album made the importance of characters in her work harder to ignore, with its third-person narratives and tweaked takes on JD Salinger stories). But whatever guise it takes, her acting is at the heart of all her work, and while there’s a tendency to focus on the headline, album-to-album transformations – like, say, the shapeshifting from slick sophisticate on Stories to rougher punk on 2004’s Uh-Huh Her – it’s the varied roleplaying within those records that really makes them come alive. It’s why she’s able to tell all manner of strange gothic folk tales of 2007’s White Chalk, or be a spirit medium for so many of war’s forgotten, forsaken voices on 2011’s Let England Shake.

And it’s why she was able to play so many different parts in 1995: murderous mother, wounded lover, cast-aside devotee. Six months after its release, Harvey performed ‘The Dancer’ at the BBC. She and her band sport sharp black suits like guests at a Mississippi Delta funeral, and she sings with her heavily shadowed eyes closed tight and a haunted grin dancing on her deathly pale face. Then, at the same session, they rip into ‘Meet Ze Monsta’, and Harvey changes completely, strutting and swivelling her hips as if possessed by Elvis’s ghost. It’s such a convincing transformation, you’d swear it was supernatural; her voodoo working at its most powerful.