Johnny Rotten by Kevin Cummins

For a band who had spent the previous 12 months outraging sections of British society, the Sex Pistols’ farewell UK gig was a strange one. The nation’s most notorious punk band went out not with a sneer but with a good-natured, energised performance in a small nightclub in West Yorkshire on Christmas Day, 1977.

In fact, Johnny Rotten, Sid Vicious, Steve Jones and Paul Cook played two shows at Ivanhoe’s in Huddersfield that day – the first being a matinee for children of striking firefighters, at which cake and presents were handed out, and an evening gig, for which admission cost £1.75.

Significantly, the evening show would be the last gig that the band would play on British soil. Within a month they would split up on tour in the US, amid acrimony between Rotten and their manager Malcolm McLaren.

There to photograph the Pistols that evening for NME was Kevin Cummins, who would go on to become one of Britain’s most highly regarded rock music photographers who has contributed to the likes of The Times, The Guardian, The Face and Vogue.

A new book, Sex Pistols: The End Is Near 25.12.77, captures the spirit of the occasion in more than 100 photographs that Cummins took that night.

“I think all Sex Pistols gigs from most of 1977 were events,” he says. “After the Bill Grundy episode at the end of 1976 [where the band provoked tabloid outrage by swearing on live television], it spiralled a bit out of control, and I think McLaren encouraged that a bit too much perhaps.

“They didn’t do regular tours that year, it was very much announce a few dates, get them banned, then in August they did some dates under assumed names so it was very difficult to find out. I was lucky in that McLaren liked me and let me know when things were happening, so we were able to organise to go.”

Cummins met opprobrium from his own family for choosing to spend Christmas Day with the Sex Pistols, rather than at home in Manchester. “Britain was a very different place in 1977, and the Sex Pistols were the antichrist,” he recalls. “Your parents hated them, and the press played up to that. The press always like a pantomime villain, so of course when I told them I was going out on Christmas Day they were outraged, especially when I told them what I was doing. My girlfriend at the time was locked in her house. Her parents wouldn’t let her go, even though she had a ticket for it.”

Cummins exchanged no more than a brief backstage hello with the band before he had to get into his preferred position for photographing the show. He says: “Trying to shoot from the audience was a bit chaotic and McLaren was always very helpful, he let me shoot from the side of the stage.”

He recalls “a great atmosphere" that night: “With the Pistols, it was almost like a secret club when people got to see them, and I think loads of people just felt grateful that they were given that opportunity. I guess because it was Christmas Day and because a room of 400 or so people managed to escape the Queen’s Speech and their own families everyone was in really high spirits. It wasn’t aggressive at all. I’d been to Sex Pistols gigs earlier in the year and the previous year that were very aggressive, this just had a really nice vibe. It was exciting and everyone was there for the same purpose, to enjoy themselves.”

The Sex Pistols live by Kevin Cummins

Cummins says no one had any inkling that it would be the Pistols’ farewell to the UK. “The band were in really good spirits because they’d had such a good time in the afternoon, so they actually played a great gig,” he remembers. “A lot of the time with the Pistols there was a lot of acrimony around, the band resented Malcolm and certain members weren’t getting on with each other but they seemed to put it all aside and it was the best show I’d seen them play for maybe 18 months.”

He feels the Pistols’ tour itinerary in the US might ultimately have contributed to their downfall: “Anybody that was au fait with what was going on in the US knew that there might be a bit of trouble out there. Malcolm didn’t pick New York, Chicago, Miami, Los Angeles, the obvious gigs, they were playing some fairly dodgy places in the Deep South and as far as they were concerned all English bands were homosexuals. They were very bigoted, and they had an attitude of, ‘We’ll show these fey English boys how we can do it here’ and it just kicked off at every gig apparently, it was awful.

“The band didn’t enjoy it. You go on your first trip to America and you want to drive over the bridge into Manhattan, you don’t want to spend seven hours on a plane and then go to somewhere that looks like the outskirts of London.”

Cummins’ interest in photography stemmed from his father and maternal grandfather who were, he says, “very keen amateurs”; he would go on to study the subject at Salford School of Art: “We always had access to a darkroom. I got my first camera when I was five and my parents actively encouraged that. I loved the magic of the darkroom, I loved playing around in there. I’d take a film on holiday and process and print it myself when I was five or six, so I was always very keen on it.

“Then when I was in my teens at my school we were hothoused to go to university and I was about to go to Warwick to study English and a friend said to me, ‘Why don’t you got to art school? That’s what you’ve always been interested in, that’s what you want to do’, and so I changed my course and college three weeks before I was due to go.”

Punk, he feels, arrived in Manchester at just the right time. Many of the bands he photographed, such as Buzzcocks, were a similar age to him. “Like a lots of lads, my main interests were music and football and my father told me the only job he thought I’d ever be qualified to do was to be a disc jockey at Maine Road,” he says. “It’s sort of ironic that I’ve earned my living photographing music and football. I graduated as punk was breaking and so I was on hand to document it. Obviously coming straight out of college and not having a job I was able to do that because I knew quite a few of the bands anyway. I just attached myself to them and took photographs whenever I could afford film.”

Together with journalist Paul Morley, Cummins bombarded the London-based NME with “fact, fiction and lies” about the Manchester music scene. “We knew they’d never come up and try and find anything out about it,” the photographer says. “They weren’t very adventurous. A lot of people, a lot of Londoners particularly, would never dream of venturing north, they tend to migrate south. We sent them stuff every single weekend, we’d go and see bands, I’d photograph them, we made our own fanzine up, we had our own mythical band, we had all sorts of stuff and if it was a quiet week I would take a picture of Howard Devoto from Buzzcocks or something and we’d send it to the NME saying, ‘Howard’s currently putting the words of Samuel Beckett to music’ and send some portentous piece in and they’d duly print it.

“The other music papers had no idea [about the things covered] in the NME because they didn’t have stringers around the country. There was all this stuff coming out of Manchester and so Sounds were going to send up one of their journalists to see if all this was actually true, so we had to keep a bit of a low profile.

“There was a scene, but there was a scene in every town and city. Whatever Liverpool thinks, we were always a musical city in Manchester. It was half-truths, but we did exaggerate it quite a lot. We were lucky as well that the BBC there was there because if there was overspill from London they’d be making The Old Grey Whistle Test in Manchester and we’d just turn up all innocent and say, ‘We’ve arranged an interview with such and such a band’ and they’d let us in. We kind of got into it that way.”

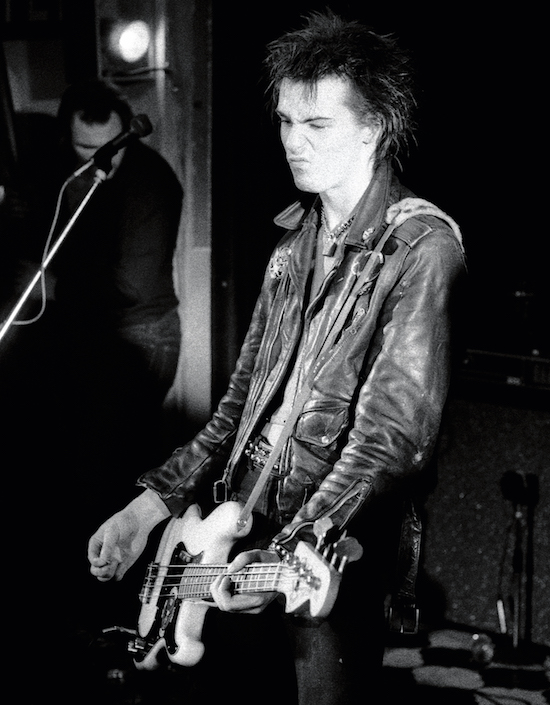

Sid Vicious by Kevin Cummins

Among Cummins’ best-known photographs are those of Ian Curtis and Joy Division. A series of shots of the band on Epping Walk Bridge in Manchester in 1979 defined their image amid a bleak post-industrial northern landscape. Cummins says the band “didn’t have a clue” about how they wanted to portray themselves. “They never really thought about it, they completely left it up to me. Some bands are great, they have a very strong idea of their own identity, but Joy Division didn’t and I think you can see that in the photos. They had only recently left school and they were wearing pretty much the clothes they’d wear for school or their work clothes. Nobody then could afford leisurewear, so it was heavy overcoats from the army surplus store on Tib Street because it was bloody cold in Manchester. So they had that look but it wasn’t contrived, it was just how most people dressed then.”

A fledgling Morrissey and The Smiths proved rather different. The singer’s understanding of the power of rock iconography even extended as far as carrying a jigsaw with his own face on it on tour.

“Morrissey was very good back then in that he had grown up understanding the music press, so he was very sure of how he wanted to look in certain situations,” Cummins says. “When I did a tour in Japan with him in 91 he was producing things out of his bag and say, ‘Let’s try this’. He was full of ideas. Some wouldn’t work and some would obviously make a good picture.

“Morrissey was the type who would wear T-shirts of himself on tour. Some of it was ironic and very knowing, he didn’t make mistakes visually back then, he was very sure of it, so my job was to get him to connect with me and compose an interesting shot from what he produced out of his magic hat.”

Cummins also captured a young Oasis en route to stardom. He believes Noel Gallagher was one of the last British musicians to emerge steeped in the imagery of rock & roll. “It was pre-digital days and they were kind of the last big band before digital kicked in and so to see them and to hear them you had to actually go out to see them [play]. It wasn’t just like it is now where if someone says, ‘Have you heard X?’ and at the click of a button you can listen to 30 seconds while you’re on the phone to somebody and make a snap decision. With Oasis, they were the last big band, really, and Noel’s aware of that, I think.

“Because they borrowed shamelessly from other musicians as well, every song the first time you heard it you were familiar with it. Because it was written in a certain pattern, you felt that familiarity with them on first hearing, which is rare with a band, I think. So I think that’s partly what it was.

“I went to the football [at the Etihad Stadium] with Noel the other day and we were talking about that and how if Oasis reformed they would only have to do one gig because it would be telecast round the world, it could be streamed live everywhere and they could do another Knebworth but they could play to billions of people on the same evening. They probably would work again afterwards but they wouldn’t need to do it again [after that], it could just be one show. Noel was saying, ‘Well, it wouldn’t be the same, because there would be 200,000 people watching it through their phones’. He said, ‘We were the last band really where you could go to a gig and nobody was taking pictures, and that’s what made it exciting’. It’s not exciting when you go to see a band and you can barely see them, you’re having to watch them on three people in front of you’s iPhone, so there’s no connection. You go to a live event to be excited. What do these people do when they film it on their phones? Do they go home that night and say, ‘I went to a great gig. I didn’t see it but I’ve got some really shaky footage’. There’s no point to it.

“It’s interesting that Jack White’s band and Madonna is doing it this week where you have to put your phone in a locked bag and you keep the bag with you but you can’t take your phone out and you can’t take pictures, you just enjoy the show, and that’s the way forward. People can’t be trusted not to take pictures, you got to actively discourage them by enforcing this.”

Johnny Rotten by Kevin Cummins

Despite being a photographer who “doesn’t shoot for gallery walls”, Cummins’ work has often been exhibited in museum and art galleries in cities such as Berlin, Bologna, Buenos Aires and most recently Austin, Texas. He has always seen his photographs as destined for print, be that in magazines, newspapers, book covers or record sleeves. “I don’t think you’re being honest with yourself if you’re not shooting for the medium that’s employing you,” he says. “When the NME existed [in print], if I was doing a shoot for them my main concern was getting a good cover shot and a good spread. If I was just taking some arty photo that wouldn’t work in newsprint, then I’m not doing my job properly. If I’ve got spare time and I’m photographing a musician for a different purpose then I’d think of the shot in a different way.

“I think when you’re shooting on newsprint you have to understand how the ink reacts to the newsprint, which is why it always had to be very contrast-y because the paper would soak it up. If you did a beautiful Ansel Adams-style grey landscape with perfect tones it would just be a grey blob in the NME, it wouldn’t have worked. You’ve got to shoot for the medium and really understand how that works. You can do a pretty picture for a record sleeve or I’m going to shoot for an exhibition then it’s fine but most of my work was done for the music press and so it had to look right on those pages.

“The way I compose – and I still do it – when I look at my pictures the way I frame stuff is to leave space in the top left-hand corner, which was always for the NME logo. I can’t get out of that habit. I still have people facing to the right and space behind their heads for the logo.”

Cummins misses the inky days of the weekly music press. “It was exciting and we felt we were kings of the world at the NME. Record companies and music papers in other countries, and certainly in America, they thought the NME was the bible, whatever was coming out of the UK, they’d look to us, and the same in Tokyo. As soon as the NME wrote about somebody the bookers in Japan would be getting these bands. Britpop was a perfect example of that because it was quite dress-y and everybody had a look. Bands like Menswear were huge in Japan just because they looked a bit fashion model-y.

“I do miss it because I think we had a great time doing it and our responsibility to the reader was to show them what bands were like. These days you get all this online and it’s different but there’s no editorial to that, really, and you’re making your own mind up, I guess. But the way people buy music has changed enormously. You’re talking about the days when a band would spend more time working out what opened side two and what closed side one on a piece of vinyl than actually recording it; now people just buy three tracks and that’s enough.”

One long-term ambition of his remains unfulfilled. Cummins says he has yet to make progress on a series of contemporary portraits of Manchester musicians that he first photographed back in the 70s, 80s and 90s. He explains: “There’s one Manchester musician – and it’s not Morrissey – who last time I photographed him, which was maybe 18 months ago, said, ‘Give me a tan and make me look two stone lighter when you retouch that picture’, so it’s a bit of a non-runner at the moment. The idea is still there and I would still like to do it, but we are talking about people here with fragile egos here.”

Sex Pistols: The End Is Near 25.12.77 is out now, published by ACC Arts Books, priced £30