"People are trapped in history. And history is trapped in them."

James Baldwin

Human nature seeks a narrative, especially in times of crisis. We look for shape and order and sometimes find comfort or chaos. Rarely, in the search, which is ironically nearly always retrospective, we find both. Future narratives are mysterious and reveal themselves in utopian, or more commonly these days, dystopian visions. The past, however, as characterised by LP Hartley in his 1953 novel The Go Between is "a foreign country. They do things differently there". In the act of looking back we think we recognise the embryonic cells of the future body we will one day inhabit. The past is a foreign country but its contours and customs are familiar to us; we know its vocabulary. And when we look back at art, music, literature, politics, cultural innovation and upheaval, we start to locate a narrative that feels neater than it ever was at the time. Music, in its traditional form of the LP is a particularly strong occult signifier in this respect.

The Romans generously gave us the most pragmatic of tools with which to measure pop culture when they bequeathed us ‘the decade’. The 20s were "roaring", the 50s were "rocking" and the 60s were "swinging". As we move further away and perspective telescopes we simplify cultural exchange that was complex at the time. Pop culture works on a 20 year nostalgia-lag. There is a renewal, discovery and reinvention cycle that is naturally fixed to generational change and ageing. The 90s are still close enough to have largely escaped this habitual homogenising. Michael Bracewell, one of our most ambitious pop cultural architects, articulated it as the decade "when surface was depth", and if we look through the prism of the image most associated with the time, Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living, this feels spot on.

And so the 90s are sometimes characterised as a vapid facsimile of the "the Sixties"; the bleached arsehole of the 1960s. Whereas the 60s had the International Times, Ready, Steady, Go! and The Feminine Mystique, the 90s had FHM, TFI Friday and Bridget Jones’ Diary. This is a gross over-simplification but the wet baggy arse of the 90s – or rather the visible, commercial crotch of it — was bloated, apathetic, mastubatory, narcissistic, nostalgic and in thrall to a Golden Age pop narrative: backward-looking, Beatles-fetishising. In a perverse way we should be thankful for this narrative, a reaction against which this website partly emerged from.

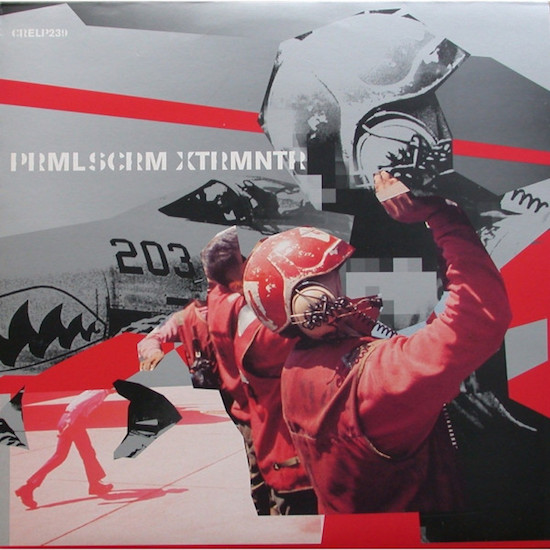

At the turn of the millennium, Y2k techno-prolapse successfully averted, Primal Scream delivered XTRMNTR, an album of such ferocity, anger and intuitive intelligence that it served as a kind of enema for the decade just past. My first encounter with Primal Scream as a 17 year old was auspicious. I spent the summer of 1991 raving in the northeast of England. Outdoors, indoors, on the moors, on the beaches, quarries, in clubs and leisure centres, seaside towns and destitute mining villages. It was Year Zero for rave and I was part of a modest convoy who travelled to Scarborough for a rave called Galactica and that day I had invested in two LPs: Screamadelica, which had been out for a month or so and the fourth album by the Pixies, Trompe le Monde. I had also invested in some psychically disarming (to say the least) LSD, in the form of a ‘double-dip purple ohm’. The bad trip that ensued was memorable for many unpleasant reasons (Julian Cope once described the experience of a bad trip to me as "feeling like a tin of tuna in the vegetable kingdom"), but most peculiarly because when I returned home and played the record, the sounds I heard (notably on sides three and four) were familiar to me from the previous night’s trip. Before midnight, and way too freaked out by the sprung dancefloor in Scarborough’s Grand Spa, I had retreated to the car, intimidated by the hardcore beats and breaks of Carl Cox and DJ Nipper, and somehow crawled through a psychedelic portal where I heard Screamadelica before I had actually listened to it. (N.B. for people who believe time travel to be impossible in this age of microdosing; anything is possible on a sledgehammer dose of LSD…)

Screamadelica represents the musical zenith of acid house, its nirvana, and this was clear to me at the time once I was capable of listening to the album in a state where my limbs weren’t melting into my stomach and I didn’t feel like my brain was boiling in a psychic pressure-cooker. It is a magical sounding album (no other song from the early 90s sounds more like an acid trip than ‘Higher Than The Sun’) and Andrew Weatherall is largely credited with sprinkling the fairy dust; it is also one of those albums that has become so canonical it is now fashionably dismissed by the holier-than-hip crowd. Commercial success can sour the legacy of the greatest records, but Screamadelica belongs in a roll-call of the most influential British albums of the early 90s alongside My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, Massive Attack’s Blue Lines and Underworld’s Dubnobasswithmyheadman, Portishead’s Dummy, and Happy Mondays’ Pills, Thrills And Bellyaches, at a moment when the club scene was still largely underground and mutating on a weekly basis, region by region. By 1995 – the first time the phrase ‘super club’ was used in Mixmag – the landscape had shifted and the Manic Street Preachers had detonated The Holy Bible, a dark masterpiece of angst and torment, whose moodboard sits somewhere on the spectrum next to XTRMNTR, which arrived as Primal Scream’s 6th album and, appropriately enough, the final Creation Records release, one month into the 21st century.

"We really all were very happy for a while, sitting around not toiling but just bullshitting and playing, but it was for such a terrible brief time, and then the punishment was beyond belief: even when we could see it, we could not believe it."

Philip K.Dick, A Scanner Darkly

At the time of its release in April 1991, Massive Attack’s Blue Lines felt like the coda to the recently concluded Operation Desert Shield aka the Gulf War. Try listening to ‘Safe From Harm’ without those newsreels spinning in your head. XTRMNTR landed squarely like an anomalous SCUD missile between two further interventions in overseas conflicts, in the Balkans and Sierra Leone respectively. Three years before the start of the Iraq War which eclipsed these earlier conflicts in the collective consciousness, Bobby Gillespie and Andrew Innes unleashed their own Weapons of Mass Destruction on an unsuspecting British public.

Gary ‘Mani’ Mounfield had resurrected himself for a Third Coming and joined the band in 1996; just as crucially Kevin Shields (partway through his 23-year paralysed sabbatical from My Bloody Valentine albums #2 and #3) had become a semi-permanent member of the band since his work on the If they Move Kill ‘Em EP (February 1998) which was received as the band’s most sonically adventurous release for more than half a decade. A reference to Sam Peckinpah and ‘his revisionist western’ The Wild Bunch, it signalled a new direction for the band, hinted at on Vanishing Point, away from a retro-bound blues, soul and R&B template into a bolder, more contemporary and abrasive sound: a relentless techno-punk onslaught. Shields remained a touring member of the band until 2006 and Primal Scream were unquestionably one of the greatest live bands on the planet in this iteration. While he mixed several of the tracks on the album (‘Accelerator’, ‘If They Move, Kill ‘Em’, and ‘Shoot Speed/ Kill Light’), Shields only actually plays on ‘Accelerator’. But his presence (with David Holmes orchestrating from the wings) is a sonic common denominator right across the album; he casts an aura of influence which might be thought of as the yang to Weatherall’s yin a decade before.

Every track on XTRMNTR was written by Innes and Gillespie and recorded at their studio, The Bunker in Primrose Hill, which has since been bulldozed to build luxury flats. They have spoken about using a ‘collage style’ of writing and recording, mixing live playing with drum loops, samples and layered soundscapes. Across their career Primal Scream have shown themselves to be keen diviners of a pop-soul sensibility but that is almost entirely absent on XTRMNTR, which is built with the toolkit of great collagists, working in the metaphorical bunker of a dawning dark epiphany. The blissed-out hugs of the late 80s, ecstasy culture and the parties in Creation’s offices that would last for weeks not days or nights, are buried in the mix here somewhere, but in muted hungover version. XTRMNTR is the tightest of albums released by any major artist at this moment, which might seem ironic when you consider this is a line-up that could mischievously be labelled a Baggy Supergroup. But the archaeology of influence prioritises artists like The MC5, The Stooges, New Order (Bernard Sumner plays on several tracks), the Bomb Squad, and Scream lodestars, CAN, above the sunnier, more melodic influences on previous albums. It is an album of rigorous and remorseless intensity; one of those transcendent pop moments where the iconography of the band’s image, the Situationist style of Gillespie’s lyric writing and the punk aesthetic of the tunes themselves are all unified.

XTRMNTR belongs in an industrial tradition and its classic tracks betray a coherent if deeply bleak vision. It is a record which seeks to unsettle, and its target is the soporific, self-indulgent 90s. This is rock & roll as apocalypse not salvation. The album represents an awakening but only in the way we wake from a bender to serve notice of recrimination on ourselves. This is an album of fear and (self)-loathing in Camden Town. On one of the timeless classic tracks on Isn’t Anything, Kevin Shields sang, "When you wake (you’re still in a dream)". XTRMNTR is like waking up to find yourself pinned to the bed by a Succubus in a terminal nightmare. This unfortunate condition is best captured in the dark heart of the album on ‘Pills’ when Gillespie repeatedly cries, "Fuck fuck shit fuck fuck shit fuck fuck shit." As therapy, it’s the closet the band ever got to Arthur Janov’s original primal scream.

The groove and aesthetic of XTMRNTR is a Taliban cut-up of protest lyrics, millennial fury and the horror of a crippled, nihilistic drug comedown. Is there a more righteous trinity of tracks on any album in the past twenty years than the 16 minute assault of ‘Acclerator’, ‘Exterminator’ and ‘Swastika Eyes’? When Gillespie sings, "Slow death injectable, narcosis, terminal/Damaged receptors, fractured speech" we hear the rattling ghost of Old Bill Burroughs, who had died three years previous. In his excellent book, William Burroughs And The Cult Of Rock n Roll (published by White Rabbit Books later this year), Casey Rae makes a case for Burroughs’ profound influence on rock from Bowie’s cut-ups, through sampling technology and a late collaboration with Kurt Cobain. Burroughs’ visionary DNA runs in tributaries through the veins of XTMRNTR. Saints and sinners, junkie hunger and junkie sickness. It is an album preoccupied with language as a virus and concepts of control, the nefarious influence of the state and the impotence of the self-medicating individual; the ultimate and despairing realisation being one that Philip K.Dick himself had arrived at decades earlier: what if the very things we see as freedom-giving and subversive (drugs, the counter-culture) are actually being used to keep us compliant?

XTRMNTR has a schizophrenic significance in the recent history of British music: it is the first great rock & roll album of the new millennium, and a snarling requiem for the decade just passed, which in its post-modern dressing-up box had plundered and cross-pollinated from the three decades which went before it. The 90s were a decade of gross contradictions. The evangelising ecstasy-fuelled spirit of the early 90s faltered and spluttered into a heavy comedown which Primal Scream embraced with the commitment and abandon of true believers. As Pike Bishop, the gang’s leader in The Wild Bunch says, "We started it together. We’ll end it together." And so just as they created the acid house masterpiece in Screamadelica, they also furnished us with its shadow narrative in the form of XTRMNTR, an album of pathological aggression and firebrand politics which serves as a brutal punctuation point for 20th century rock & roll.

It is only with the benefit of a generation’s gap that we see Screamadelica and XTRMNTR are neat definers of what was happening in Britain’s pre-millennial pop culture. XTRMNTR closes with arguably Primal Scream’s greatest song, ‘Shoot Speed/Kill Light’, a motorik-blues of colossal and overwhelming simplicity driven by Mani’s bassline. Bobby Gillespie’s lyrical contribution has been reduced to the bare essence of the band’s permanently heightened and stimulated condition. Trapped in a fugue of amphetamines, disgusted by the apathy of the rave generation who sold out or cashed-in, XTRMNTR captures one of the great British bands a tunnel of extraordinarily dark creativity, uneasily pitched between hedonism and activism.