Honestly, in post-digital late capitalism, everything is junk, isn’t it? It’s all excess. Particles of media and sounds and images that pile up on our desktops subsuming and drowning the cultural consciousness. Does anyone actually memorise songs anymore? Do they extrapolate meaningful knowledge from texts? It’s all just digital, ephemeral stuff accumulating until that ominous portent emerges on our smart phone screens: "iPhone Storage Full.” We have lost our senses of materiality. That Baudrillard quote about the world having ever increasing information but ever decreasing meaning has been repeated to the point of redundancy, and yet its relevance only strengthens the further we slip into the abyss of liquid modernity.

We are all grasping for meaning. It’s not just that our reality is bleak – it is, of course – it’s that it is totally fluid, chaotic, and hard to pin down. Aside from the tactile pleasure or pain I experience and endure, I often wonder whether I exist at all. We are all pining to be reoriented to a semblance of material reality.

Materiality is the strength and allure of artist Ryan Foerster’s work. The artist maintains a fascination with his physical reality that pulsates throughout his oeuvre. Nothing is discarded. Georges Bataille wrote of “the Accursed Share” as a necessary expenditure, a waste or excess, that was fundamental to human progress as we know it. Bataille believed that excess wasn’t a byproduct but an end unto itself. But as capitalism has rapidly depleted the earth of its natural resources and rendered our planet an apocalyptic doomsday scenario of rising sea levels, dangerously incoherent weather patterns, famine, and the erosion of our greatest cities, it is becoming clear that Bataille’s theory of excess doesn’t hold in late capitalism. Excess is killing us.

Foerster refuses to let excess remain as it is. He finds new purposes for the discarded objects, for the trash, for the decaying photographs, and for the over-expended materials of our overstimulated world by viewing these things in the context of the environment that they inhabit and by dislocating those things from that environment by filtering them through his perception. Artist Jordan Wolfson said recently in a podcasted conversation with the playwright provocateur Jeremy O. Harris that an artwork is an artist’s way of allowing you to see how they see the world, and that we are “fucking lucky” to experience this. I feel particularly luck-struck looking at Foerster’s art, which not only gives me a glimpse through Foerster’s eyes but also provides me a particular sense of interacting with the material environment.

His work is also indicative of an economic necessity of making use of the world’s excess. Foerster initially gained attention for his peculiar photographic practice in which he used alchemical processes to expose the scientific properties of photography itself. The images he captured he allowed to fade and decay with the background around them. Conservation is a tenet of photography, and Foerster has connected the conservation of photography to a larger practice of conservation of the physical environment around him. Foerster’s incorporation of discarded detritus into his art stems from a period of financial insolvency around the time the artist moved to New York from Canada in 2009, just after the financial crash that rendered the artist’s assistant jobs he had been taking mote.

He started taking long walks around the city and began picking things up off the street – pieces of scrap metal and wood – that he would then bring home and find ways to combine them with his photographic prints. He repurposed both environmental dejection and his economic dejection into a new process of recording experiences that heightened the conceptual focus of his photography. “It all added different layers to how I understood seeing and remembering things,” he told Bomb Magazinein 2015.

The ability to apply his analytical eye and artistic craftsmanship to the discarded objects of the world continues to inform his practice. At Foerster’s new exhibition at CLEARING in Brooklyn, ZOLTOG 99, photography plays a smaller role than it ever previously has in his work. The works in the show – ranging from mixed-media assemblages, to drawings and watercolours, to sculptural tableaux, to a thirty-minute video – have been named by their creator as “zoltogs” and the title of the show simultaneously references the artist’s childhood tendency to spraypaint his favourite hockey players’ names and jerseys on the forts he would create in his parents’ backyard as well as the iconic Coney Island fortune teller Zoltar who infamously made Tom Hanks big in that dreadful piece of ‘80s white suburban cinema Big (apologies to the Penny Marshall defenders of the world).

The show utilizes the gallery’s substantial space, enveloping its three separate exhibitions in a hybrid of environmental and industrial grotesquerie. Akin to certain high-low culture fetishizing arthouse Americana filmmakers, such as the exploitation meets cinema verité styles of directors like Giuseppe Andrews or early Harmony Korine, a Ryan Foerster exhibition envelopes you in the artist’s singular, perverse, funny and disturbing vision of the American world around him. Like said filmmakers, Foerster elevates the macabre beauty of impoverished America’s artefacts. The mixed-media piece, Targets emphasizes this point; the discarded Target bag glued to the canvas illustrates the wastefulness of American culture. Target, with its insatiable hunger for gobbling the consumerist habits of lower-middle to middle class Americans, embodies the nihilist waste of American capitalism. At the same time, Foerster finds beauty in the waste, recontextualises it, and makes space for it to thrive in the context of art.

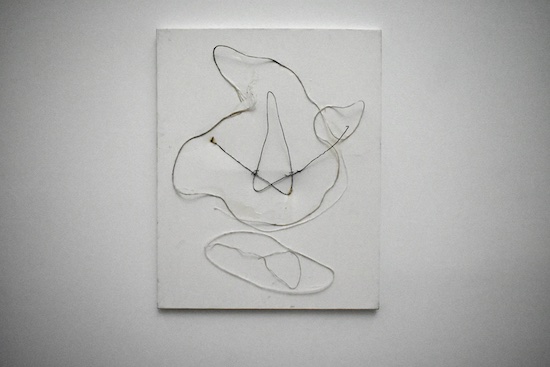

The notable departure of the exhibition is a series of sixty-eight mixed-media collages, drawings, watercolours, and paintings. Despite the incorporation of traditional art making methods in to his practice, however, the works don’t feel conceptually incoherent amongst Foerster’s photography and junk installations. Whereas his photos and found objects embody Foerster’s interiority as projected onto his exterior world, these works are glimpses or recorded snapshots of his interiority outright: “they came from dreams I had, nightmares remembered, feelings I felt, air I tried to breathe,” writes Foerster on the pieces. “The memories of different things are not completely unlike the documentary photos I take or my thinking that led me to incorporate the different materials I considered as valid form of documents worth showing to tell a story.”

Like Foerster’s photographs – imagistic documents in material decay – these works allude to the corrosion of memory. Much like Leyland Kirby’s music which repurposed and manipulated vintage ballroom recordings yielding an uncanny and unsettling temporal loop, Foerster’s works exploit the “crackle” of the utilised materials to haunting – or dare I say “hauntological” – effect. In Self-Shadow Sun, a figures appears to be fading, or disintegrating, from view before our eyes. In Birth, a magazine cut-out of a baby being delivered could refer to trauma and its tendency to fade from the concreteness of our conscious mind into the deterritorialised unconscious mind. Foerster doesn’t just use discarded materials to make art, he uses discarded materials to emphasise our discarded memories. Memories, he suggests, are both fixed and fluid entities. Like Brutalist architecture, the foundation of the memory material remains while its form and content deteriorates.

Various series of abstract assemblages litter the spaces: spraypaint, acrylic, coffee, tape measure, and sunflower seeds represent just some of the materials that Foerster has brought into his practice. An interplay between the weird and the eerie develops. The scattered junk is out of place. It feels like it shouldn’t be there. At the same time, the traditional markings of an art exhibition – labels, paintings, coherent press materials – are missing. The binary separating art show and reality is blurred. These random assemblages lead to a totemic movie theatre entitled Come For to and Carry my Home. Like the bare skeleton of a wedding tent, the naked pipes that cohese its structure are adorned with various dystopian artefacts: dead animals, skulls, junk, and so on.

The theatre is set up to watch a thirty-minute film of the same name. The video collects footage shot by Foerster from the end of 2014 through now and serves to “express better how [the artist] feel[s] and think[s] than [he] can get across in words.” The scenes provide a sense of geography and temporality to the works on display throughout the exhibition. It also focuses on environmental dislocation and excess, reminding viewers of the horrors wrought upon by ecology through late capitalism. A cheetah skulks from side to side in its cage at a zoo, pining for the habitat it once knew. A horseshoe crab pathetically scuttles back towards an ocean full of pollution and peril. Butchers carry gutted pigs slumped over their shoulders into their shops from the streets. The scenes course with sadism and humour, with Foerster documenting and attempting to make sense of the nonsensical world around him.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes wrote that “what the Photograph repeats to infinity has only occurred once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially.” But Foerster has expanded on this limited notion of photography by ensuring that these moments do in fact ring out existentially. In his work, nothing – captured images, found pieces of junk, his brief fantasies and dreams – go to waste. Instead, he doesn’t just capture moments, but freezes his perceptions of these moments, and aestheticises the ways in which these moments fade in and out of his interiority throughout his existence. All art is, more or less, about how the artist sees the world. But for Foerster, his art is actually an encapsulation of exactly how he sees, inhabits, and remembers the world.

Ryan Foerster is at Clearing, Brooklyn, until 18 January