Like it was most Wednesday nights, Occasions was packed to the rafters when i-D magazine held the Sheffield leg of its grandly titled “World Tour” on 25 April 1990. The reason this particular venue and date was picked was simple: Cuba, Occasions’ infamous midweek party, was one of the hottest weekly events in the North of England.

The importance of the party was first outlined six months earlier in Jocks magazine, when Warp Records founders Steve Beckett, Rob Mitchell and Robert Gordon explained the role Cuba played in shaping the Yorkshire Bleep & Bass sound. “About 30% of the stuff played at Cuba is Sheffield originated,” Gordon explained. “A lot of demo tapes are tried out, it’s total hardcore dance.”

Winston Hazel, one of Cuba’s resident DJs, echoed Gordon’s points in an interview with Rob Young for his 2005 history of Warp Records. “The first breed of bedroom producers started bringing recordings into Cuba to hear their tracks played on a club soundsystem and to gauge a dancefloor response,” he said. “Nearly all the Warp tracks were first given dancefloor air and tested on a well-versed crowd. LFO, the Step, Tomas and Tuff Little Unit were all given maximum rotation.”

Despite being on a Wednesday night, Cuba was a pull not only for serious dancers from across Yorkshire and the Midlands, but also signed and unsigned producers from elsewhere. Mark Millington, Martin Williams, Paul Edmeade, Tomas Stewart and David Duncan all recall semi-regular visits, while Hazel and DJ partner Richard Barratt remember testing out some early LFO cuts in the presence of Mark Bell and Gez Varley. “I remember playing one particular demo they brought down – maybe ‘Track 4’ or ‘Mentok 1’ – and the crowd going mental,” Barratt says. “I looked at Mark Bell, and he was stood there stony-faced. There was no reaction to what was going on at all.”

Cuba was popping off even more than usual when i-D magazine rolled into town. It was a heaving mass of sweaty bodies, with almost every significant figure from the local scene present amongst the packed crowd of Occasions regulars, glassy-eyed students, football lads and fashion-conscious girls. Most were wearing brass dog tags embossed with the i-D logo and the date and location of the party – a novel replacement for tickets that was reportedly the work of Cuba and Jive Turkey co-promoter Matt Swift.

“It was a really big deal at the time,” Sheffield DJ Pipes remembers. “I remember it being over-capacity and that there were some live sets. That guy Man Machine played, probably because he was on Outer Rhythm which at that point had a deal with Warp.”

Man Machine was the recording alias of Ed Stretton, a London-based radio-producer-turned Acid House evangelist who first rose to prominence as one half of Jack ‘N’ Chill, whose 1987 cut ‘The Jack That House Built’ was one of Britain’s first crossover House tracks. He’d re-emerged as Man Machine the previous autumn with a self-titled track that boasted ludicrously bass-heavy remixes by the Forgemasters.

“I did about eight or so live dates and that party in Sheffield was one of the better ones,” he remembers. “I used to dress up in this robot-inspired outfit with loads of lights on it – a really hot and heavy costume. I’m not sure what the crowd thought but, from memory, my set went down well.”

There was another live act on the line-up, too, though their involvement wasn’t advertised beforehand: local industrial funk heroes Cabaret Voltaire, fresh from the release of their new album on Parlophone, Laidback, Groovy & Nasty. It had landed to mixed reviews two months earlier and saw Richard H Kirk and Stephen Mallinder joining the dots between Industrial Funk, Chicago House (via collaborations with Windy City originals Marshall Jefferson and Ten City), and the "Sheffield House sound" (as i-D put it) of Bleep & Bass.

“Performing live and playing ‘godfathers’ for the night, Cabaret Voltaire were treated as highly as they are regarded,” wrote Simon Dudfield in his later i-D magazine report. “But the most fuss was caused by DJs Parrot and Winston, with a following any band would envy, proving that the House sound of Sheffield has the potential to be massive.”

With the help of Barratt and Hazel, Dudfield was able to distill the essence of the ‘Sheffield sound’ better than any writer had done before, putting the now-familiar Bleep blueprint into print for all to absorb, admire and act upon. “Hard underground tracks with heavy Reggae basslines is a sound unique to Sheffield,” Hazel told Dudfield. “The black scene, with its emphasis on hardcore and its emphasis on bass, has put ideas into whites and it has rubbed off onto whites into a heavier sound.”

Dudfield remarked that the combination of ‘sparse electronic bleeps’ and ‘heavy bass pulse’ typified ‘the Sheffield sound’: “Emphasizing the black/white crossover, Winston celebrates the fact that Reggae bass is meeting white electronics and producing something that is exclusive to the city.”

While you could argue that it wasn’t unique to the city – Leeds and Bradford had produced the earliest records in the style, and the cut that kicked it all off was made in Manchester – Dudfield was certainly correct in making a link to the “white electronics” that had dominated Sheffield’s recent musical heritage.

A decade earlier, Sheffield had been one of the few British outposts of experimental electronic music with a small scene of dedicated pioneers who obsessed over synthesizers rather than guitars. Some of these had gone on to great commercial success with a more pop-leaning sound – think Human League, Heaven 17 and ABC – while others had stuck to their guns and produced futuristic, industrial-strength experiments inspired by the growing bleakness of their poverty-strewn, concrete-clad city. In truth, it was a small collection of like-minded “futurists” who turned Sheffield on to electronic music, with Cabaret Voltaire, who began experimenting with tapes and synthesizers way back in 1973, being the first and arguably greatest of the lot.

Initially founded by bored school friends Kirk, Mallinder and Chris Watson, the “Cabs” Punk-era work was decidedly noisy, bleak and cutting edge, with the band blending Musique Concrète style sound collage, grumpy guitars and morose, stylized vocals. Alongside Throbbing Gristle, they later became flag-bearers for the Industrial sound of electronic music, before embracing other influences – most notably Electrofunk and the bass-heavy sound of Dub Reggae.

Their records became hugely influential, inspiring black teenagers in Detroit, New York and Chicago as much as the tracks they loved by Kraftwerk, Yellow Magic Orchestra, Depeche Mode and fellow Sheffielders the Human League. In fact, the three founding fathers of the Motor City Techno movement – Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson – were primarily inspired by European electronic music, with the sounds of the Steel City towards the top of their list of influences.

When Sheffield began to find its own dance music sound in the late 1980s, it could be said that Techno had come home. "All these industrial places influence the music you make," Warp co-founder Rob Mitchell told journalist Jon Savage in 1993. "Electronic music is relevant because of the subliminal influence of industrial sounds. You go around Sheffield, and it’s full of crap concrete architecture built in the 1960s; you go down to an area called the Canyon, and you have these massive black factories belching out smoke, banging away. They don’t sound a lot different from the music.”

In Simon Dudfield’s i-D report, Richard H Kirk was a bit blunter. “Everything people make here is very hard,” he said. “Perhaps it does have something to do with the heritage.” Barratt, too, was typically forthright when asked about the links between the dance sounds of Chicago, Detroit and Sheffield: “Detroit and Chicago are both Northern American towns. Chicago is a steel town. Sheffield is a Northern steel city in England. Work it out for yourself.”

When it came to commenting on Sheffield’s electronic music pedigree and unspoken trans-Atlantic connections, Richard Barratt probably felt like he was stating the obvious. A year before i-D waxed lyrical about the sparse, bass-heavy sound of his home city, he’d already spotted a correlation between the homegrown records his friends were making and the clanking Industrial Funk of Cabaret Voltaire.

Barratt had been playing their records since he started DJing – especially the more floor-friendly cuts such as ‘Sensoria’, ‘Sex, Money, Freaks’ and ‘Crackdown’ – and had already developed friendships with both Richard H Kirk and Stephen Mallinder. In fact, he’d even spent some time with Kirk in the pair’s legendary Western Works studio, a former cutlery workshop that had previously hosted studio sessions from the likes of 23 Skidoo, Joy Division and Chakk. “Richard and Mal were very welcoming, especially to non-musicians like me who were interested in making music,” Barratt says. “They were great – very encouraging.’

It’s certainly true that both members of Cabaret Voltaire believed in offering opportunities to people from within the Sheffield scene, especially those with interesting ideas or who shared their militant socialist beliefs (which, in Sheffield at the time, was pretty much everyone on the alternative music scene). Fittingly, prior to Richard H Kirk moving in – quite literally, as he lived there for a period – Western Works had been the local headquarters of the Socialist Workers Party.

“It still had posters on the wall from that movement when we arrived,” Kirk told me during a 2013 interview. “That was all interesting, so we left it on the walls. Quite a few bands came through there, some of them well known like The Fall and New Order, some just local bands who came and went. As we had a studio and rehearsal space we weren’t using all the time, we just thought we’d get other people in. It was also somewhere to go after the pubs closed. I always used to describe it as Andy Warhol’s Factory on a small budget. It was a meeting place and somewhere to hang out.”

Crucially, Kirk and Mallinder were also regular club-goers and could often be seen hanging out at Jive Turkey after it launched in November 1985. “Jive Turkey had kind of grown up with us,” Mallinder says. “We were involved from the moment it started. We did our performance for the [Old Grey] Whistle Test there, even though what we were doing was quite different to what they were playing in the club. We took Winston and Parrot with us on tour as our DJs – we were all mates and part of the same Sheffield scene.”

Barratt’s sessions in Western Works were initially limited, and by the middle of 1988 he had other things on his mind, specifically the surprise success of ‘Hustle To The Music’ by The Funky Worm, a record he’d made with Mark Brydon and friends Julie Stewart and Carl Munsen. Brydon had invited the others into the studio after orchestrating the making of Krush’s big-selling ‘House Arrest’ single with Robert Gordon the previous year.

‘Hustle To The Music’ was a suitably funky affair that mixed classic Disco and Soul samples with sweaty blasts of Rare Groove-friendly breakbeats, a Chicago House-influenced acid bassline, jazzy keys and occasional blasts of saxophone provided by Chakk member Sim Lister. Brydon and Barratt had no expectancy that it would be a hit anywhere other than on the dancefloor at Jive Turkey. In fact, its initial limited FON Records release sold out, and the track became popular in clubs throughout the UK.

Predictably, major labels soon came calling. They’d seen the success of FON’s previous in-house dance production for Krush and wanted a piece of the action. WEA won the bidding war, ordered new remixes from T-Coy and Graeme Park, and made a video in which Barratt and Munsen pranced around giant plant pots in ridiculous outfits. Despite this abomination – or perhaps because of it – the record rose to number 13 in the UK singles chart, was licensed for release in other territories (most notably the United States) and left WEA hungry for more Funky Worm records.

“It was great that it was a half-arsed hit, but it was a double-edged sword,” Barratt sighs. “We had no idea what to do next and the follow-up records were terrible. We ended up being pulled every each way to try and make a Pop record. None of us had a clue – not us, not the people at FON, and definitely not WEA. We just ended up with some bland shit. By the end of the process I was screaming to get away.”

By the time the record ascended the charts, Barratt’s frustration was about to boil over. ‘Voodoo Ray’ and ‘The Theme‘ had blown him away, while the heavy, minimalist tracks being produced by his Yorkshire contemporaries – and particularly Forgemasters’ ‘Track With No Name’ – excited him much more than the Pop-dance records that WEA was ordering the Funky Worm to make.

“Stuck in a deal with a major label making insipid Pop crap and hearing the emerging Bleep sound made me want to weep,” Barratt admits. “It was like someone had captured the heartbeat of our scene and pressed it onto plastic.”

Looking for an escape, Barratt popped round to visit Richard H Kirk at Western Works with the idea of collaborating on some underground Techno tracks. Kirk was receptive, not least because he was getting increasingly frustrated with the demands of Cabaret Voltaire’s own major label masters, the EMI-owned Parlophone Records.

The Cabs previous album, 1987’s Code, had not been a rip-roaring commercial success. Although it was co-produced by Adrian Sherwood, a producer with impeccable underground credentials, the set was far more influenced by American Electrofunk and dancefloor-focused Synth-Pop than the band’s more experimental early work. It came accompanied by glossy videos and an extensive marketing campaign, both of which rubbed Kirk up the wrong way. Mallinder, a more laidback, outgoing and cheerful character than his intense, forthright and occasionally paranoid bandmate, fitted the role of ‘Pop star’ more than Kirk ever would.

“I interviewed Cabaret Voltaire a number of times, and Richard could be hard work,” sometime i-D and The Face journalist Vaughan Allen remembers. “He spent most of the interviews talking about pornography. He was a very different character from Mal [Stephen Mallinder], who was lovely. I can forgive Richard though because it was partly that aspect of his character that made him one of the true geniuses of electronic music.”

When it came to recording a follow-up to Code, Parlophone urged Cabaret Voltaire to think big. As a result, Kirk and Mallinder decided to explore their love of black American dance music further by decamping to Chicago to work with one of the city’s most successful House producers, Marshall Jefferson.

“The world had changed a little bit with what happened in 1988, both down in London and up north, so quite naturally we shifted with it,” Mallinder muses. ‘We wanted to retain our connection with black American music. We’d worked with American producers before, like Afrika Bambaataa and John ‘Tokes’ Potoker, so it wasn’t alien to us. We were breathing the air of the club scene, like a lot of people, and that’s why the album developed as it did.”

The original idea had been to disrupt their usual routine of recording at Western Works and then mixing the subsequent tracks elsewhere, hence writing and producing a chunk of the album in Chicago. It wasn’t quite as successful a process as they’d hoped, despite getting roughly half of the album in the can, and on their return to the UK Kirk was more frustrated than he had been for some time.

‘I wasn’t very happy where Cabaret Voltaire was going at that point,” Kirk explained in a 2017 interview with Daniel Dylan Wray. “I thought that the Groovy, Laidback and Nasty album was a really watered down version of Cabaret Voltaire. EMI were chucking all this money at us and getting it totally wrong.”

The album had yet to be completed when Richard Barratt turned up at Kirk’s door inviting him to collaborate on some Techno tracks. “Listening to the early Bleep tracks, I thought that although the obvious influences were Reggae, House and Techno, I thought it would be interesting to do something with Richard,” Barratt explains. “In Sheffield, there were these older electronic musicians who’d inspired a lot of that early American House and Techno stuff so to me it made sense.”

Despite the duo’s longstanding deals with WEA and EMI respectively, they pressed ahead with regular studio sessions at Western Works, creating music with Warp Records in mind. Kirk was a past master at making clanking electronic music that sounded like it was roughly forged from pure Sheffield steel, while Barratt – a hero to Sheffield dancers as DJ Parrot – had an instinctive grasp of hooks, basslines, and the very specific demands of contemporary dancefloors.

They began by jamming out a Detroit and Chicago influenced Techno cut that placed sampled electronics from Yellow Magic Orchestra’s ‘Computer Games’ and spacey synth sounds atop a squelchy bassline and a sweaty drum machine rhythm track rich in handclap-heavy fills. The track was introduced by a spoken word sample from Close Encounters of the Third Kind: “Everything’s ready, you’re on the dark side of the moon: play the five tones.”

Over the next few weeks, the track was developed further with the addition of a whole new bleeping melody line that would soon become one of the most iconic lead lines in dance music history. The pair added a fatter, weightier bassline, and the kind of ghostly chords that made the record sound like it had been beamed down from some far-off planet.

They called the cut ‘Testone’, and by autumn 1989 it was already causing a commotion on the dancefloors of Cuba and Jive Turkey. Warp’s co-founders mentioned it in interviews as a forthcoming attraction but declined to reveal the identities of the producers behind it, aside from saying that the artist was known as Sweet Exorcist (a name borrowed from the title of a Curtis Mayfield record that Barratt and Kirk both loved).

“Before and at the time it came out, Kirky was signed to EMI, and I was still signed to Warners as part of the Funky Worm deal, so we had to keep quiet,” Barratt says. ‘There could have been some trouble if the labels had found out straight away. If we’d taken it to either company, they wouldn’t have understood it and would have put a stop to it coming out. We were pretty sneaky originally.”

While they initially remained in the shadows, it didn’t take long for word to get out about the record. Accompanied by a pair of ghostly, mind-altering reworks (‘Testtwo‘ and ‘Testthree’), ‘Testone’ first appeared in stores in early 1990, spending seven weeks in the lower reaches of the top 100 singles chart. It became as ubiquitous as ‘Dextrous’, ‘The Theme‘ and ‘Track With No Name’ and was quickly followed by a remix 12” featuring superb remixes from Robert Gordon. These featured Gordon’s trademark Steppers-influenced rhythmic shuffle, even heavier bass and an arrangement capable of doing even more dancefloor damage than Kirk and Barratt’s original versions. “That remix is a Techno nerd’s wet dream,” Robert Gordon laughs. “I did it at FON with all the best equipment. It’s the most high-tech mix I ever did.”

Kirk and Gordon were, in some regards, kindred spirits. “I learned so much from Robert,” Kirk told me in 2013. “He taught me a lot in terms of sonics and programming on the Atari. He knows so much about bass.”

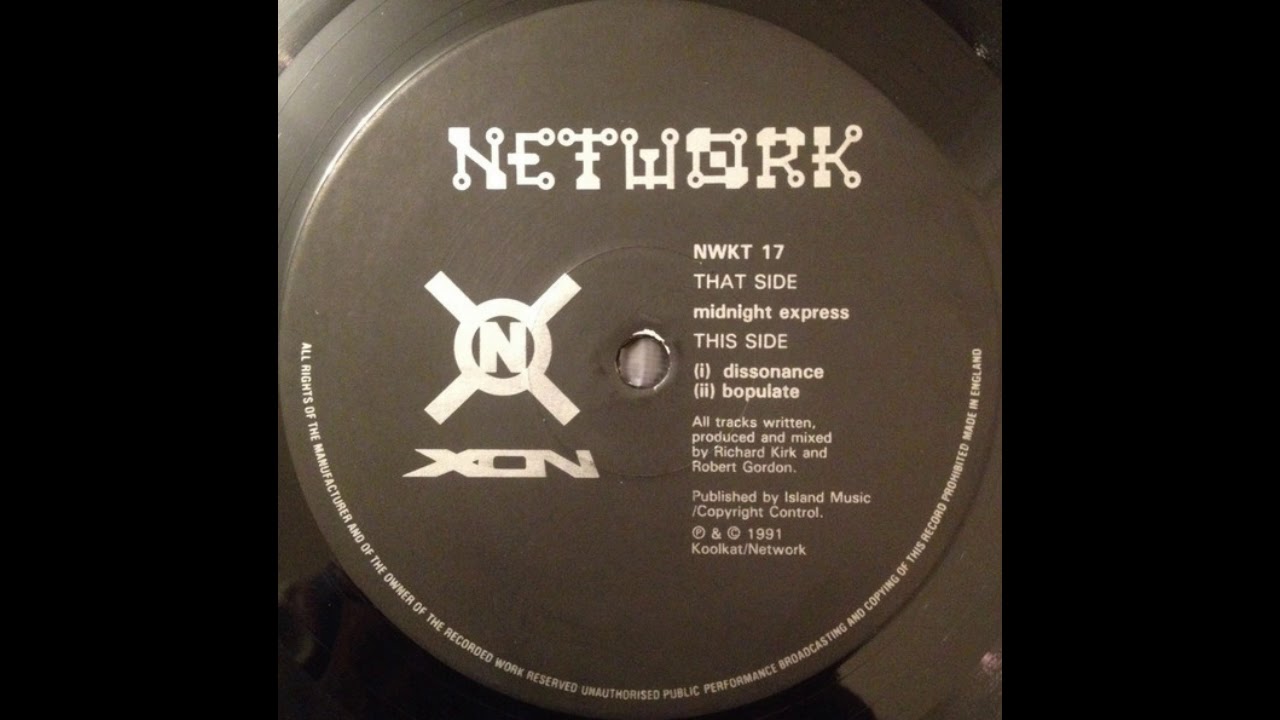

The two later got together at Western Works to record what would become The Mood Set EP on Network Records. Credited to XON, the EP contains a trio of weird, psychedelic and off-kilter Techno tracks that are noticeably deeper than any of the other Bleep & Bass-era Techno cuts that emerged from the Steel City.

“We did that record over about three days at Western Works,” Kirk explained. “Rob brought over all of his analogue stuff – he had some great old synthesizers and sequencers. We just set everything up and did it. We did a track a day, producing and mixing everything within three days. Later we tried to do some other stuff, but it never came out as well. We actually signed a deal with Network to do another 12” and an album, but sadly it never happened.”

To help get Laidback, Groovy & Nasty across the finish line, Robert Gordon and Mark Brydon were enlisted to help co-produce and mix some tracks that would more accurately reflect the heavyweight club sound that was rapidly developing in the Cabs’ home city. “I was very comfortable working with the Cabs because I’d played some bass on Code, but the sessions were weird,’ Brydon remembers. “When they came into the studio, Richard would be hovering around saying, ‘You can’t change that!’ We did think it was odd the Cabs having us help them make dance music. At that point, Mal [Stephen Mallinder] was singing more and they were both fed up of not having hit records. I think they saw it as an opportunity to still be cool but have hits.”

The involvement of the FON Force boys resulted in the undisputed highlight of Laidback, Groovy & Nasty – lead single ‘Easy Life’. While still a Cabaret Voltaire record, it boasted warm and weighty bass, Bleep style lead lines and enough energy to make sure it moved the crowd at Occasions. Fittingly, it came with a trio of remixes from Robert Gordon – a vocal-free “Vocal Mix” and two decidedly strange dubs – and a ‘Jive Turkey Mix’ that was overseen by Richard Barratt under his DJ Parrot alias.

“I didn’t do the remix, but I did contribute the African style drum break that’s sampled on it,” he remembers. “I remember that during the session I had to lie down on the floor because somebody was smoking this really evil marijuana.” Robert Gordon remembers Barratt requesting a drag before it all went wrong. “It killed me,” Barratt says. “I was lying down between the speakers, underneath the mixing desk for at least an hour. I’m not a dope smoker anyway, but that experience certainly didn’t help.”

Laidback, Groovy & Nasty was the beginning of the end for Cabaret Voltaire’s strained relationship with EMI Records. In the years that followed, they produced a string of records that showcased their particular take on contemporary Techno and Electro, most notably the Body & Soul album on Belgian imprint Les Disques de Crepsicule (the lead single, ‘What Is Real’, is basically Bleep & Bass with vocals). Kirk and Mallinder’s relationship was beginning to fray around the edges, with the former spending more time at Western Works working on solo projects and Sweet Exorcist tracks.

By the time they got round to making a follow-up to ‘Testone’, Richard Barratt and Richard H Kirk were getting bored of Bleep & Bass, or at least the sparse, simplistic melodies that were now starting to appear on every second UK-made club cut. “The Bleeps bandwagon is rolling,” wrote Matthew Collin in a December 1990 piece on Sweet Exorcist in i-D magazine. “Even London acts are getting in on it, for Christ’s sake. The sound is becoming a millstone around its creators’ necks.”

Barratt seemed to agree with Collin’s concerns. “People just think that you can put some bleeps and heavy bass on anything and make loads of money,’ he was quoted as saying. “There will be a flood of records like that – there has been already.”

Sweet Exorcist’s response was to coin a new term for the sound of the records they were now making: Clonk. The track that gave their new micro-genre its name was certainly not lowest common denominator Bleep & Bass. Both of the 12” versions – subtitled ‘Freebass’ and ‘Homebass’ respectively – were mixed by Robert Gordon, who once again ensured that the sub-bass was deep, heavy and capable of coursing through the bodies of dancers at Cuba and Jive Turkey.

Rich in off-kilter, African-influenced drum machine polyrhythms, modem style electronic pulses and alien-sounding minor key motifs, Clonk was the most underground and leftfield club cuts yet to emerge from Yorkshire. For the most part, it sounded like someone had dropped an ecstasy tablet, gone wild in a steel mill and committed the ensuing metallic cacophony to wax.

It was followed shortly after by ‘Per Clonk’, a low-slung chunk of bass-heavy Techno-Funk which played around with some of the same elements as its predecessor, and the deliciously clanking and percussive insanity of ‘Samba’, where off-kilter synthesized marimba melodies danced above quirky vocal samples, mind-mangling electronics and a typically rumbling bassline. Both were brilliant but bonkers, offering rhythms that appealed to Jazz-dancers but left many DJs confused.

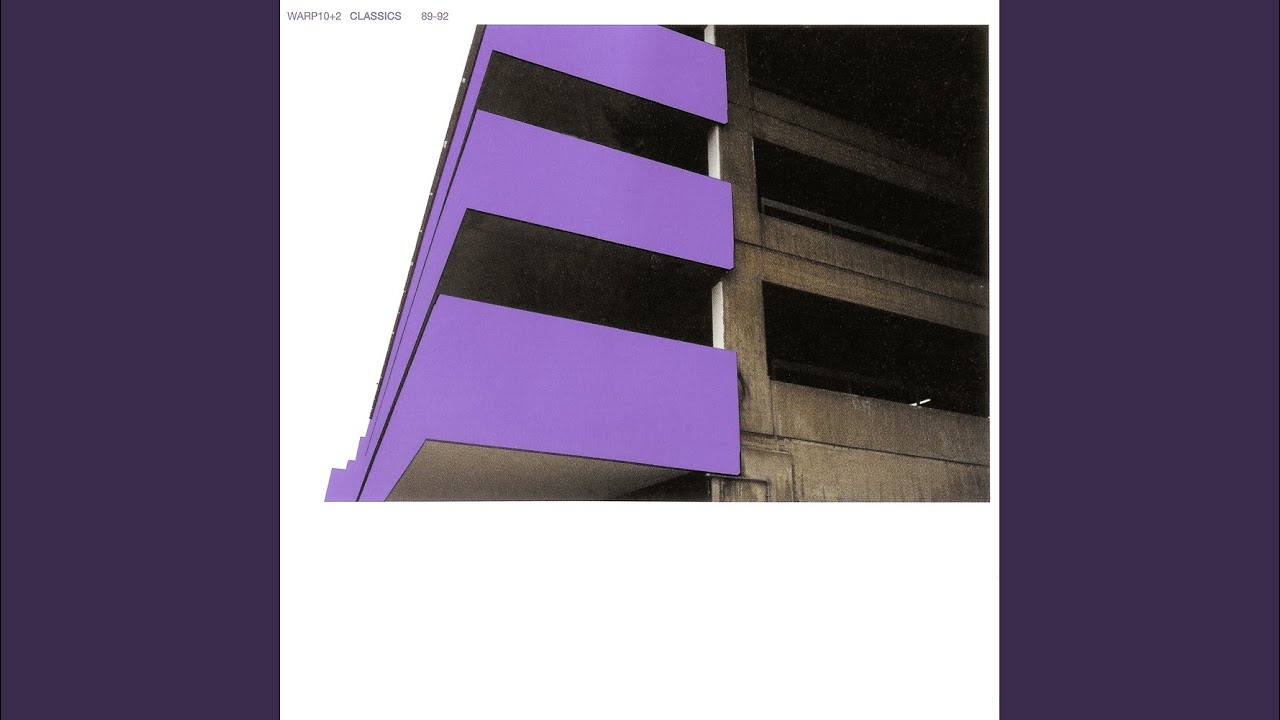

Before parting company with Warp Records, there was one final blast of polyrhythmic, dancefloor-focused insanity from Sweet Exorcist: the CC EP, a suite of tracks based around re-using and re-processing the same basic set of percussion and vocal samples. There were still bleeps present – especially on the wild ‘Testone’ sequel ‘Trick Jack’, whose name may have doffed a cap to another Warp-signed act, Tricky Disco – but, by and large, the vibe was far funkier, with samples lifted from Latin-tinged Post-Punk records and rubbery Jazz-Funk cuts. This was not Bleep & Bass or even Clonk, but rather some form of mutant industrial Techno-Funk.

The duo had trailed this sound in the i-D magazine interview. “What we’re making is modern electronic Funk music,” Barratt said. “I hate it when people call it rave music – it’s not. Rave music is just rehashed and re-sampled music – lowest common denominator.”

By the time that the “CC EP was repackaged as the first album on Warp Records, the label’s co-founders were already thinking about where to go next. While Bleep & Bass as a sound had not yet run its course – and Warp would release another handful of industrial-strength Yorkshire Techno records before the spring of 1992 – the style was changing rapidly thanks to the input of others outside of Sheffield, Leeds and Bradford. What had started as records made for a very specific audience had captured the imagination of a whole generation of DJs, dancers and producers across the UK and beyond. It was now they, not the sound’s pioneers, who would shape the future sound of British “Bass music”.

Join the Future by Matt Anniss is published by Velocity Press