For an ostensibly apolitical person Catalan singer Rosalía Vila Tobella has endured a deeply political 12 months, caught up in the whirlwind of Spain’s acute personality crisis, where every move is divisive and every argument political.

2019 has seen Rosalía grow into Spain’s first global music star since Julio Iglesias; its first credible pop success since forever. Rosalía is massive in Spain, a superstar whose records top the charts and whose tours sell out arenas. In a country that likes to talk – and loves to argue – she has become the number one gossip mag staple, her statements and silences alike studied for feelings this way and that, her success piggybacked by entirely contradictory parties.

Vox, the vile far right party known for its anti-Catalan policies and misogyny, apparently used the music of this young Catalan woman at its rallies in early 2019. (Rosalía, in her one overtly political statement for the year, later told them to fuck off.) Catalan nationalists praised her for releasing Catalan language song Milionària in July, while centre-right party Ciutadans, which viciously opposes Catalan independence, saw Rosalía’s speech at the MTV Music awards in August as backing Spanish unity.

Through it all, Rosalía has maintained her political silence – the one "Fuck Vox" tweet aside – skipping over questions on Catalan independence with perfectly weighted answers that come down gently on neither side. "I am Catalan and at the same time when I go to the south [of Spain] I feel like I belong there," she said in an interview with El Mundo. "I feel like I am as much from Barcelona as I am from Madrid and Seville, which also inspire me." Rather than dousing the flames of debate, though, this has only fanned them, as if people somehow deserve an opinion to rail against / chain themselves to, from a young woman who owes them very close to nothing.

Despite herself, Rosalía has become a lens through which modern, divided Spain can be viewed, as the country endures one of the darkest times in modern history. Spain is a young democracy, a country that only emerged from the Franco dictatorship after the death of the hated (and, in some nefarious quarters, loved) dictator in 1975. By the time of Rosalía’s birth, in September 1993, the country was ruled by the PSOE, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, which had just won its fourth consecutive election.

What happened in Spain, the country’s emergence onto the global and cultural economy, was something close to a miracle. It’s hard now for the 83m tourists who visit Spain for its benign weather and liberal nightlife to imagine that little more than four decades ago this was a country under Franco’s dictatorship. But to emerge from the Franco era uncrushed, Spain had to do a lot of forgiving and forgetting. There was probably no other way. Franco’s supporters were still there, in the upper echelons of society, too numerous to be anything other than tolerated. And, if forgetting may have stuck in the craw, the policy at least seemed to work, as Spain’s democracy blossomed.

Live in Spain long enough – and I have been here eight years – and it is clear that not so much has been forgotten, after all. The last 12 months, in which Rosalía’s career has taken off, has seen the rise of Vox to become the country’s third political force, while the fight over Catalan independence, its seeds sown over hundreds of year of troubled history with Spain, has continued to rage. Catalonia itself has been split down the middle by the independence debate – I know of at least one extended family whose monthly lunches have split into pro-and anti-independence parties – while the divide between Catalonia and the rest of Spain has rarely been so profound.

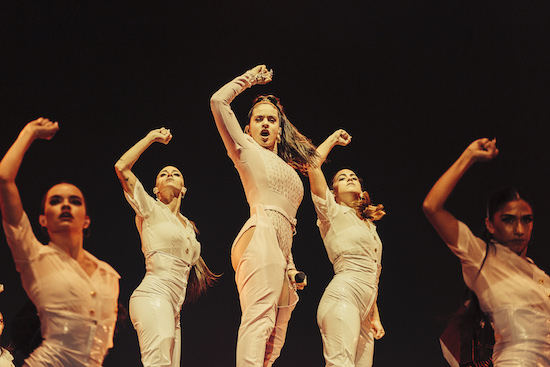

Into all this has come Rosalía: not just a star but a Catalan star, who sings largely in Spanish and employs the flamenco music of Andalusia. And she has succeeded where few flamenco icons before her have succeeded, in taking flamenco – or her version of flamenco – to the heart of the global pop charts. At a time when Spanish national unity is taking a battering, Rosalía’s success seems turbo charged to cause maximum chaos, tripping over the linguistic and cultural boundaries that lie behind so much national pride.

To understand Rosalía’s position – to grasp why she is so important to modern Spain – you need to understand at least three things about the country, Catalonia and her music.

Firstly, geographical context is important. Catalonia may be an economic powerhouse in Spain, responsible for roughly 19% of its economy, but on a global political level it is small fry. As part of a young democracy, too, Catalonia tends to look outside of Spain for wider approval. Catalan nationalism, as such, is often (but not always) associated with support for the EU. Many Catalans would love to see Catalonia as an independent state within the EU, while Spain, for all its sometimes suffocating national pride, has a similarly international view, recognising the role the EU has played in bringing Spain to prosperity.

Politically, this helps to explain why the foreign eye is so important in the battle over Catalan independence. Whenever there is significant news around Catalan independence – be it demonstration or riot – the Catalan press likes to pour over what the international media are saying. The actions of the Committees for the Defence of the Republic (CDR) in fighting for Catalan independence – closing Barcelona airport or blocking the frontier with France – are also specifically aimed at generating international interest, by hitting infrastructure where foreign interests will be affected.

You see the same thirst for global attention in local coverage of Rosalía. Every media outlet, from Texas to Tampere, loves a local artist made good. But Rosalía’s success is covered in almost embarrassing detail by the Catalan media, her every international move, from playing Coachella to appearing on Later… With Jools Holland, shoved under the spotlight. You may remember how important Oasis and Cool Britannia were for New Labour Britain in the mid 1990s. Well, Rosalía is like this phenomenon spat out cubed for the gossipy social media age. She is hugely important to Catalonia and Spain as a success, a mark that Catalonia (and/or Spain, depending on your perspective) is a player on a global level, a reflection of Catalan (and/or Spanish) ingenuity and cultural clout, right when Catalonia (and/or Spain) needs it most.

This, in turn, makes Rosalía’s cultural history all the more important. Rosalía may be Catalan but she sings largely in Spanish and uses the flamenco tradition that carries the influence of Andalusian and Romani culture. Calling her a Spanish success, then, is not as outrageous as it might seem. Catalonia has its own musical traditions – including the Catalan rumba style that Rosalía used on Milionària – but it is not the traditional home of flamenco.

So what, you might argue? Rosalía studied flamenco for a decade before releasing her first record. She is hardly an unthinking pretender, keen to ride the flamenco wave wherever it may take her.

This is undoubtedly true. And Rosalía has never shied away from acknowledging the influence of legendary flamenco artists like Camarón de la Isla on her work. Some media have even called her flamenco’s best global ambassador. But Spanish traditions hold an importance it is hard for outsiders to grasp, which should be seen in the light of Franco’s rule. Franco’s regime was authoritarian and centralist: practices like flamenco and bull fighting were promoted as national traditions, while customs not considered "Spanish" – often Catalan and Basque traditions – were suppressed.

This created a situation in Spain, whereby local traditions are incredibly important and not to be messed with. Even the tiniest Spanish villages have their annual local fiestas, where the same folkloric traditions are repeated year after year with no thought for modernisation or change. This helps to explain the deplorable popularity of blackface in Spanish festive celebration, with white men painting their skin to play King Balthazar in the traditional Reyes processions. To outsiders, this is outrageous. To many locals (but not all), it is just part of the tradition.

The kind of cultural appropriation that sees Spaniards jump on trap beats with barely a thought for their origins may go pretty much unnoticed in Spain. But Rosalía using flamenco music has created controversy here, with activist Noelia Cortés claiming that the singer uses Romani culture "as something cool as part of her disguise but we aren’t important for her socially speaking."

But Franco didn’t just suppress local Spanish traditions. He also crushed their languages, revoking the official statute afforded to the Basque, Galician and Catalan languages by the Spanish Republic.

Spain remains marked by this half a decade on, a country divided by language. Catalan, for example, is widely spoken and promoted in Catalonia, used in public schools and local administration as one of four official languages, alongside Spanish, Aranese and Catalan Sign Language. According to the 2011 census 73.2% of the Catalan population aged two or more can speak Catalan and 55.8% can write it. But while this works well in practice, politically it is extremely controversial. Some non-Catalan speakers feel excluded by the use of Catalan, while others fear that the use of Catalan in schools means their children won’t properly learn Spanish.

As a result, speaking Catalan or Spanish is often seen as a political act, even when nothing political is intended. When Rosalía thanked the audience in English at the 2019 MTV Awards for allowing her to sing in Spanish, some people saw it as a deliberate snub to Catalan independence. When she released her first song in Catalan, Milionària, many Catalans nationalists were thrilled by its success. Others, however, were unhappy with her use of Spanish-isms in the lyrics, which feature the word "cumpleanys" – a corruption of the Spanish word "cumpleaños" – for birthday, instead of the Catalan "aniversari".

If you feel there’s something vaguely depressing in Rosalía’s music – so inventive and full of life – being dragged kicking and screaming into a political debate that the singer appears to have little time for, then I would agree. But that, frankly, is life in Spain right now: politicised to within an inch of its life and horribly divided.

And yet, if you look for it, hope remains. Beyond the frantic claims and counter claims of Rosalía’s supposed political views, beyond the insults and the media fury that Milionària inflamed, millions of people, in Spain and beyond, have got on with enjoying her music, whatever language it may be in. A video from Rosalía’s performance at the 2019 Mad Cool festival – in Madrid, no less – shows thousands of people singing also to Milionària in Catalan, while the comments under Milionària’s official YouTube video display the kind of level-headed thinking that social media sometimes seems to have banished. "How lovely Catalan sounds," says one BLACK SHIRT. "And this is coming from an Andalusian. Enough fighting. Art is art. And long live cultural diversity."