In a 2018 interview with VICE, the 28-year-old songwriter and musician William Doyle explained the plunge into depression and anxiety that resulted in the artist prematurely disbanding his techno-saturated electronic-pop project East India Youth and taking exile in the suburbs of York in March 2016. “The month when [2015 full-length] Culture of Volume came out, I was having panic attacks, I was drinking far too much, my diet was terrible, we were playing shows a lot…”

Full disclosure, I loved both of Doyle’s full-length releases, both Culture of Volume and its 2014 predecessor Full of Strife, and found within Doyle’s music something that I felt was missing from the contemporary pop landscape. His sound was lush, expansive, ambitious, and unapologetically intellectual. His music was in homage to and in celebration of a specific history of British pop music – everything from Bowie to Roxy Music to Eno to Pet Shop Boys to Soft Cell to Underworld – while still by no means shunning the harder-edged electronic abstractions of more contemporary producers like Perc. That said, I also understood where some of the common criticism around the East India Youth project was coming from. “It comes off as an academic pursuit,” wrote Ian Cohen in his review of Culture of Volume for Pitchfork. “A veritable thesis on the legends of avant-garde pop.”

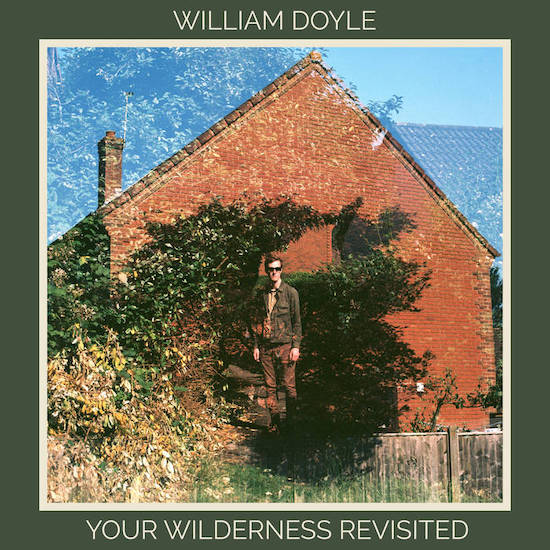

If taking time to treat his anxiety has allowed Doyle to engage once again with his music, then abandoning the East India Youth moniker in favour of his given name has allowed him to find more confidence within his own expression. On Doyle’s first album under his own name, Your Wilderness Revisited Doyle doesn’t just immerse himself in the history of the music he loves, but he immerses himself in the suburbs in which he grew up. Perhaps because of this, Doyle sounds more than ever like he is trusting the power of his own creativity over the strength of his record collection.

If he was a savvy curator while recording as East India Youth, he has emerged as an auteur when making music under his own name. “The architecture and the planning of the modern British suburb influenced this album as much as the experiences and emotions I superimposed upon that landscape at a formative age,” writes Doyle of the influence of the county of Hampshire on this album. “I started creating in these places, I started to expand myself in these places, I grappled with grief and loss in these places.”

The theme of restoration manifests within the album’s first minute. The first five seconds of opening track ‘Millersdale’ (named after the suburb in which Doyle lived) are pure jackhammering noise in the vein of vintage British power electronics like Whitehouse. It’s a jarring and thrilling way to open what is essentially a work of polished art pop. But at the five second mark, a lush piano chord progression kicks in that builds half way into the first minute before Doyle sings. “And so everything fell upon me, cascading indefinitely….” The ugly noise of the song’s opening moments emphasizes Doyle’s state of psychological deterioration that he was experiencing as he ditched the East India Youth moniker, and as the song builds towards the sublime the artist declares the Hampshire suburb where he grew up as a place of renewal and restoration. He’s seeing his home with new eyes.

Though perhaps delighting in a purer emotional palette than on his East India Youth releases, Doyle is still very much an intellectual pop performer. There is a mathematical precision to the way he blends the outré tendencies of Berlin-era Bowie and the more melody-oriented Krautrock acts with the unbridled collective joy of electro-pop. This balance is similar to what Brian Eno sought to achieve on his earlier solo albums like Another Green World, so it shouldn’t surprise that Eno has expressed admiration for the younger artist: the pair met for the first time for a 2015 Guardian article (written by the Quietus’ Luke Turner

) in which the two intellectuals debated who was the worse songwriter.

In a showing of creative camaraderie, Eno features on ‘Design Guide’ opening the track with a thoughtful bit of spoken word:

The presence of gateways

The adaptability within the open space

Decreasing dependency

A sense of community.

The song builds towards a pulsating rapture of pop music at its most glorious and free. But true to the styles of both Doyle and Eno, it keeps listeners alert as it closes with glistening string arrangements, buzzing electronics, and a guitar solo. “Labyrinthian into forever,” repeats Doyle as the track comes to its conclusion.

The critics who have accused Doyle of being overly-academic are, in some ways, right. As stated above, he’s more of a musical intellectual than he is a conventional songwriter. But Doyle tempers his penchant for theorizing on architecture and space with Your Wilderness Revisited’s elemental concept of removing oneself from urban bustle to be overtaken by the simplistic beauty of the suburbs. And one way that Doyle consistently invites us in is through the power of his vocals, which have never sounded better.

Doyle’s voice has always been unique –somewhere in between the nasal androgyny of Placebo’s Brian Molko and the high camp theatrics of Marc Almond – but on Your Wilderness Revisited Doyle’s singing achieves an exuberantly operatic quality. On ‘An Orchestral Depth,’ a collaboration with the writer and filmmaker Jonathan Meades, Doyle sings along to a simple piano progression and swirl of electronic sound in a manner that sounds melancholically overwhelmed by the suburban sublime that he is immersed in. “That’s when all the colour turned an orchestral depth,” he sings. “Magnolia flourished.”

A theme that courses throughout Your Wilderness Revisited is Doyle finding new appreciation in the suburban world he grew up in. It’s a refreshing attempt to disavow the drugs, success, exhaustion and general ego trips that defined his earlier recording career. But his appreciation of nature diverts from the Walden standard in that Doyle is finding appreciation in the suburban nature of concrete and housing blocks.

In a sense, this record aims for the noblest and most Proust-ian ambitions that an artwork can undertake. Proust believed that “habit” was the enemy of expression: “Most of our faculties lie dormant because they can rely upon Habit,” wrote Proust. “Which knows what there is to be done and has no need of their services.” Habit dulls our senses, Proust suggests, and stops us from appreciating common beauty. On Your Wilderness Revisited , Doyle sheds himself of the bad habits he developed as an emergent successful recording artist in East India Youth and takes on the role of the Proustian artist. He takes pleasure in and extrapolates beauty from the suburbs that raised him, and takes pains to share that beauty with us.