When Art Kleps, soon to be founder of the Neo-American Church, visited Timothy Leary’s Castalia Foundation at Milbrook, upstate New York, he was disappointed to find the “most dangerous man in America” away from home. Instead, while chatting to Castalia co-founder Ralph Metzner and Leary’s daughter Susan one day in the kitchen, he encountered “a man with unreadable features, dressed in slacks, a sports coat and a fedora with a ribbon of photographs around the brim, [who] came twirling into the room … as the apparition spun round the table muttering to himself, Ralph’s eyes narrowed, and Susan took a deep breath and held it. He acted as though he wanted to sit down on one of the empty chairs but couldn’t figure out how to do it. I pulled one out for him, which seemed to piss him off. He moved his arms angrily and sputtered. Still twirling, he moved out of the room. Susan exhaled. ‘What the fuck?’, I asked. ‘Michael Hollingshead’, Ralph said, poker faced as usual.”

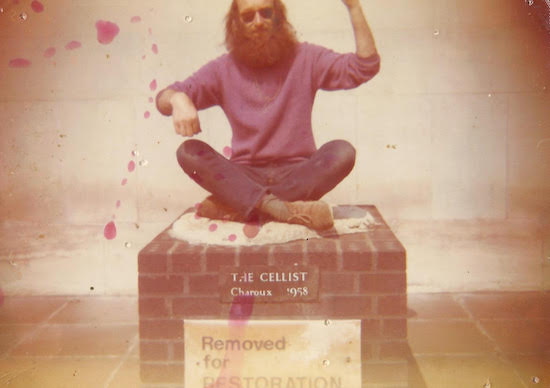

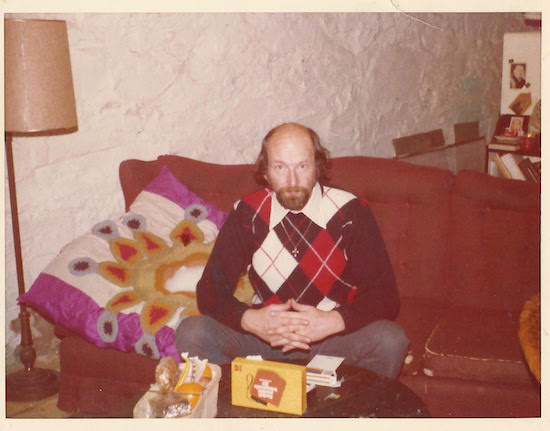

There are two photographs on the front jacket of Andy Roberts’ new book, Divine Rascal. One shows a mild-faced man with short, balding hair, a dark suit, and carefully fastened tie. He looks like he could have been a civil servant or the regional branch manager of a high street bank, with his eyebrows slightly raised and weak chin. The other cuts a different figure altogether: face almost totally obscured by wild, long hair, red-rimmed sunglasses and a shaggy beard. In blue jeans and a mauve sweatshirt, he sits cross-legged, with his arms poised as if playing an invisible cello, badly.

The discrepancy between these two images – both the same man, Michael Hollingshead (né Michael Shinkfield) – is at the heart of the mystery Roberts seeks to unravel in Divine Rascal. The first is Hollingshead’s passport photo, stamped 12 September 1973. The second was taken around the same time, on a plinth outside the Royal Albert Hall, by which time Hollingshead had divested himself of his name and native Georgie accent, discovered LSD thanks to the interests of his friend Dr John Beresford, introduced the drug to an initially reticent Timothy Leary and assisted Leary during the notorious Concord Prison Experiment, returned to London to found the World Psychedelic Centre in a first floor Belgravia flat, travelled to Kathmandu, and even led a sort of commune-cum-cult on a remote Scottish island.

The question that remains hanging over these two images on the book’s dust jacket is: which was the mask and which the real Michael? Was the passport photo mere straight world camouflage, intended to throw off the set any customs officers who might otherwise have been inclined to search his most-likely drug-stuffed belongings? Or was the long-hair little more than a hippy wig, a veneer of countercultural cool adopted with the sole purpose of facilitating access to the kind of circles that would make it easy for Hollingshead to feed his numerous addictions to drugs, alcohol, and sex?

Over the course of his strange and storied life, Hollingshead would be a presenter on Danish radio, an executive secretary at the Institute for British-American Cultural Exchange in New York, an inmate at HMP Wormwood Scrubs, a university librarian at Harvard, the publisher of a poetry magazine in Nepal, a freelance writer for High Times and other magazines, and a pioneering installation artist in Edinburgh. That he had also been a particularly craven and ruthless sort of conman and sexual predator throughout this same period should nonetheless cast doubt on his own wide-eyed self-description as “the man who turned on the world”, a kind of guru to the world psychedelic movement, or in Leary’s words, “a raffish clown of a god, but unmistakably divine.”

There is a popular narrative of the 1960s counterculture as a moment of unmitigated freedom, of peace and love and creative experimentation in new forms of living, that ‘died’ in 1969 under the twin blows of Altamont and the Tate-LaBianca murders. But without quite disparaging the utopia dreams of the summer of love entirely, Roberts’ fascinating and highly readable book at least demonstrates that that dark underside, the susceptibility of psychedelic countercultures to swindlers and charlatans, abuses of power and mental and physical violence of all sorts, was always there, lurking just beneath the surface.

Hollingshead’s daughter had apparently insisted to the author that he write the book “warts and all”, and the subject comes out of the resulting study a deeply ambiguous figure – a “catalyst”, as several people in the book say, for sure, who seemed able to make things happen by sheer force of will alone. But equally something rather darker, shadier. There were clearly others like Hollingshead at the time, grifters and opportunists who exploited the idealism of the hippies for their own ends – many of whom are still being celebrated in one quarter or another for their supposed spirit or daring. But few have had quite the influence or impact of Hollingshead while remaining so mysterious. In spite – or perhaps because – of the fact that it finally leaves more questions open than it answers, Divine Rascal provides a crucial missing page of the history of the present, offering a necessary set of complications to an over-mythologised era.

Divine Rascal: On the Trail of LSD’s Cosmic Courier, Michael Hollingshead, by Andy Roberts is published by Strange Attractor Press