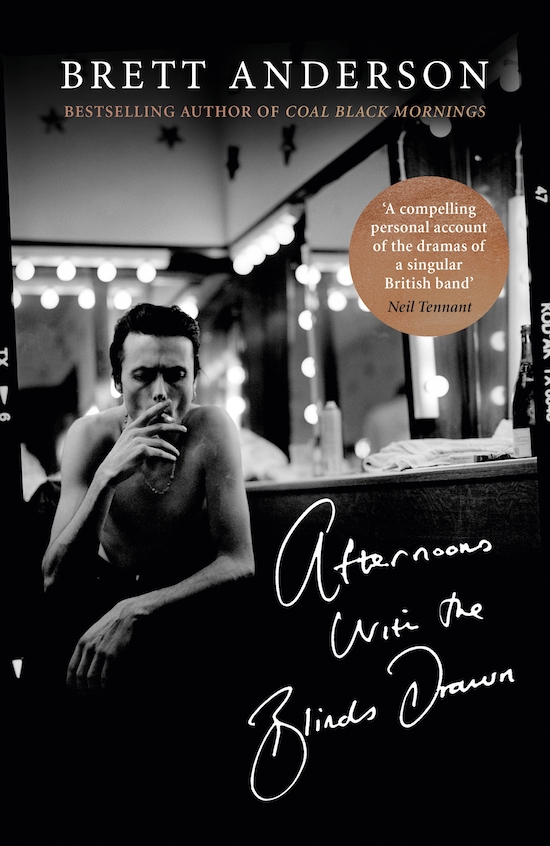

Portrait by Paul Khera

Coal Black Mornings, the first volume of Brett Anderson’s memoir, was a haunting and unusual addition to the genre, eschewing the devices and gimmickry that are the principle selling points of a rock star confessional, for a harrowingly reflective and thoughtful overview of his early years. Anderson took the reader back to a time before the music, to the experiences that informed the songs, albums, and eventual career trajectory, and in doing so, circumnavigated the years of his triumph during which he rose to public prominence and critical acclaim.

His onus on the creatively formative period that preceded success, the tender portraits of his family, particularly his complicated relationship with his father, a man who may have wished he had the life his son had, and the recollections of an England that has vanished so completely as to no longer be a place, offered a more unique and heartfelt history than the celebrity tittle-tattle fans might have thought they wanted. To do anything comparable with the second volume, a story Anderson vowed not to tell, would at once be easier for him – his material would span the glory days of his career – yet harder, for how could the tenderness of the first book survive grubby contact with the reality of wild adulation and Britpop, a “movement" he admits to despising?

Perhaps to his own surprise Volume II, Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn, strikes the same ruminative notes as the earlier volume, again subverting convention and expectation to avoid cliche and disappointment, written in the vulnerable and careful voice of its antecedent. Instead of dishing up insider gossip, Anderson mentions none of his rivals or contemporaries by name, assiduously sticking to the frequently scorned advice of “if have nothing nice to say, I say nothing”. Portraits of associates, friends and ex-friends are generous, forensic but fair, and there is no attempt to airbrush or underplay anyone else’s role in contributing to Suede’s imperial phase.

Knowing that the man he became in this second volume, is not as not as sympathetic as the youth he was in the first, Anderson goes on to slay the most prominent elephant of all, himself, through pages of literary flagellation few writers could self-administer uncoerced.

Driven by the desire to work out what really happened to him, Anderson’s writing follows an unashamedly conceptual arc (“archetypes”, “convergence theory” and “postmodern play of mirrors” all appear on a single page), constituting a historical inquiry into the motives and processes that lay behind his best and worst work, by way of remorseless self-analysis, painful descriptions of how others must have seen him, and an attempt to grasp why we all think we are right at the time. The light shed and insight shared in these two volumes places them in the same covetable space as Springsteen’s Born To Run or Dylan’s Chronicles, and would be worth cherishing even if Brett Anderson was the reason why you never liked Suede in the first place.

Musicians often write books to sustain and propagate a persona that they have developed over a career, not deconstruct one in a spirit of enquiry. This book reads like it was written by that hidden aspect of yourself that wrote the songs in private, and not the public alter ego we saw perform them…

Brett Anderson: Absolutely, that is the main premise of the book, that it wasn’t going to be written by the Brett Anderson persona but whoever the real person behind it was. The reason why Coal Black Mornings ended where it did was because my public persona didn’t exist then, and I deliberately stopped the story before it had been formed. What I didn’t know was whether I could actually write another book in that same voice I had developed in the first, dealing with the next period of my life, and not drift into public persona I had created by then. It was a massive conundrum for me, as people might be familiar with the events and that version of me, and expect something consistent with that, while I knew I wanted a more personal and interesting story, told in the natural voice of the first book.

There is something I want to be clear about though, this thing with the persona we’re talking about is that it wasn’t necessarily false in the way people understand that to be. I wasn’t just the man behind the mask manipulating people’s view of me, because to inhabit a persona you have to believe in that persona too. Looking back it’s possible to wonder how much of it is really yourself, as it is you and not you at the same time, but all of it still comes from you. You are the one doing it. I mean, everyone manufactures personas all time. People in the public eye simply amplify the process, and the lens of the media then helps magnify and distort the original amplification. The “you” that sits down and watches TV with your family is very different from the “you” sitting here now, but that doesn’t mean that your public self is some Svengali like manipulation of reality. The persona you decide to project says as much about who you are as your private self does. And it was only through growing up, growing up and not giving up these past eleven years, and having kids who you can’t fob off with a persona, that I went through the slow and painful process of taking apart the nuts and bolts of what mine was made of.

The book does come up short on after dinner speaking anecdotage. Although it is often very funny, it doesn’t seem to see its function as to amuse, does it?

BA: No, not at all. The book is a search into what happened to me in those years of success and fame, and what effect that had on me as a person, not a parade of all my achievements, where I ask the reader to look at me and love me. Like the first book, I used my writing as a sounding board very like therapy, and used the questions I was asking of myself to work out my own shit.

Portrait by Pat Pope

Notes from therapy don’t normally make for very interesting reading though…

BA: They don’t, and I knew I was running a risk. In one of my favourite reviews of Coal Black Mornings the reviewer writes, having given it two or three stars out of five, I’m not sure which is the more dismissive number, ‘this book is very well written but the big problem I had with it in the end is it is all about him, him, him!’ Well of course it is, it’s a memoir! Memoir has to take the risk of being indulgent to work.

But for a memoir, I found you very impatient with your own perspective. There’s very little self justification or score settling, often it’s like you’re trying to establish something very close to historical objectivity? Even though you keep saying that it is impossible to do that.

BA: I realise I wanted to know everything that was going on around me at that time, that wasn’t just me or to merely repeat or excuse how I saw things then. And I really didn’t want to fall into one of the lazy tropes of the genre which is just to sit there and slag off other bands. There is a vitriol in there, but I apply it to movements and features of the period, not individuals, partly because I know how the media works now. As soon as you slag off a name, that’s all your book becomes, and you lose all control or ownership of context, and simply end up as a line in a feature in quotes of the year. A memoir is about context, a complex tapestry, not a motormouth series of quotes, and you don’t want to lose that by being petty or boring, or revisiting past rivalries. I mean, who cares who ticked me off? The crazy thing is that there are people who want you to name names and write that kind of book, but I wasn’t prepared to.

But readers are more used to engaging with a work of that kind, aren’t they, who blew coke up whose arsehole?

BA: Absolutely, but the books that do that are the same story with the names changed, you know, the amusing band shenanigans, all the japery, the dirt, all of it is essentially the same tale every time. But that is the expectation, and to be honest, critics can be just as predictable. I’ve had reviews saying that Coal Black Mornings was really good but who was it really for, as it doesn’t sit comfortably in the genre they think it is supposed to be in. But for me that’s a good thing. It’s meant to be more ambitious and about trying to get to the bottom of things and to understand life. Basically the opposite of a series of oft repeated anecdotes. The anecdotes that I have included are the things that are important to me that no one else could have ever known about, because they were purely personal or because sometimes there was simply no one else there to observe them. Whether it’s the beautiful girl who comes up to me just to tell me my band are shit, or the cheese and pickle sandwich I took with me on my first flight to America, these were the things I wanted to share so that I would know they had really happened. You know, the strange and quirky little things that give your life back to you, as they thread in and out of the story everyone else thinks they know…

You are hard on yourself in the book, but you are also very hard on your own music, which from a fan’s point of view might be tough to take. Reading that you have never rated your most successful singles, or that people’s favourite songs had working titles like ‘Pisspot’ and ‘Sombre Bongoes’ for example…

BA: Yeah, ‘Stay Together’, ‘Electricity’, the Head Music title track, and ‘The Power’, yeah, I take the sword to them all, but I had to be that self critical in order to be convincing. If I just sat there saying, “I’m a fucking genius and everything I have done is brilliant” anything else I would say would carry zero weight! Especially if I then want to go on and talk about the songs I really do still love, ‘Heroine’, ‘Killing Of A Flash Boy’, ‘Sleeping Pills’, the list goes on. It’s all part of subverting the myth of the god given seer, like the bit where I talk about myself honestly as a musician and admit that I am not a particularly talented one, but what I do have is that I just don’t fucking give up. That admission for me was a moment of truth, it just isn’t what most musicians say, and so another attack on the supposed elegance of my persona. But in the same way I view myself at points in my past as a different person, I see some of those songs as written by a different person, and that is why the flaws so easily reveal themselves to me. As for being hard on myself, again, I had to be. My mistakes were entirely my own and no one else’s fault, certainly not the fault of any childhood trauma or external stuff, and I needed to take responsibility for that. My descent into hell came from being romantically attached to the notion of the artist as a genius that accepts no limits or boundaries, it was that simple.

Do you think the experience of the relatively fallow and low periods in your career helped you develop the sensibility and humility with which you wrote this memoir? That continual and unbroken success may have robbed you of certain insights that disappointment helped provide?

BA: Yes, the end of the band meant I was able to jump off the bandwagon I had been on and develop a different perspective. Those were key years for me as an artist, that I had to have away from Suede, before we came back again. Experiencing struggle and failure, having had success, was crucial for me. I loved making solo records but it did start to feel like a bit of a vanity project as you do need an audience, and there is a certain point where if you drop below a particular level, you begin to wonder whether it is still worth doing. The work may still stand up, but if there’s just a select group you are appealing to, buttressed by family and friends, you can feel like the basic relationship you need with an audience, in order to create, is breaking down. And with having a family too, I thought I couldn’t afford to go on like that anymore. A performance, a book, a song, all these things require an audience, it’s a plea, you are projecting your voice out there and you require an echo in return. Otherwise you’d just stay in your own room and write for yourself, which is what some artists claim to do, but it’s an attitude I have never shared. Because half the point of creating anything is the reaction. I’ve never understood the cliche of the artist that only creates for themselves and never reads their own press.

You have to be Kafka to really not care what happens to your work. Most artists hope for perpetual immortality, on their more modest days.

BA: But did even Kafka really not care though?

He did leave his work with his best friend and literary executor to destroy.

BA: Exactly, his best friend and literary executor! Interesting that he chose a man who thought he was genius for that task! If he really felt that way he should have given everything to someone who really didn’t give a shit about him or his work.

Contingency and chance is one of the big themes of your book. One of the very few contemporaries you name, and then very affectionately, is Loz Hardy of Kingmaker whose fortunes you contrast with yours. You seem to be asking did you succeed, and he fail, because of the hidden hand of destiny, Darwinian necessity and artistic merit, or has the whole of your and his career been the most monstrous fluke?

BA: I thought long and hard about whether to involve Loz in any of this, and there is a part of me that felt bad about it, and so I tried to be sensitive in how I talked about him, as I have warmth for him and always really liked him. But I had to include him. We were thrown together by the Melody Maker’s “dog shit and diamonds” piece, a gladiatorial contest they set up where we were used as symbols for different musical and aesthetic tendencies, and there was no way for me to explore the questions I wanted to if I ignored that. The fact is Kingmaker did not go onto achieve success, but I hope I didn’t trample on them when I refer back to that point where we found ourselves in the same place. I genuinely wanted to work out whether things happened for us in the only way they could have, and if you can judge your own worth on the basis of success, as the ultimate criteria, or if it is all down to chance in the end.

You go on to say that the neglect of great art makes you wonder whether it is all chance, however much it might suit you not to think so…

BA: Exactly, look at Echo And The Bunnymen for fuck’s sake! They’ve made amazing music but why aren’t they then given the prestige they deserve, whereas so may of their less talented contemporaries fill up stadiums at the drop of hat? How can you resolve it? It’s unresolvable! But I think you need to believe in destiny wholeheartedly to make it at anything, and it is easy to when everything is going right, you know “my success is my destined birthright!’, but then how can you have any framework or belief system left if you embrace destiny and then fuck up? You’d be complicit in your own fall. Even then though, you can make failure work for you, and realise the fuck-ups were necessary too, and that you learn from them and they therefore feed your future successes, so you’re kind of led back into destiny again. The thing is if you are happy with where you have got to in life, and looking at things from a place of satisfaction, then you literally can’t really regret anything, as the fuck ups are part of the journey that led you to where you are, and are as easily as important as the successes.

Photograph courtesy of Phillip Williams

You make a number of complimentary references to the old music press in the book, even when they turned on you, which is rare for a musician…

BA: God yeah, we’re culturally less well off for their folding, don’t you think so? That whole Punch And Judy journalism and playground tribalism produced so many great bands and so much great discussion no matter how ugly it got. Those papers were like a music factory. A lot of modern music writing, with some very obvious exceptions that I love, is too dry and balanced. Growing up to a point where you can’t be violently partial means you lose something of the enthusiasm and passion that draws you to music. Music writing needs to be a little bit impetuous because music is impetuous. It’s easy to think it was all divisive and unnecessarily nasty, but it needed to be, that was its job, which encouraged it to issue challenges and be creative in its own right too. Which was great, providing they were saying nice things about us!

How has the creative process changed for you now that you are no longer committed to releasing album after album in quick succession, a process you say that led to the creation of some inferior work; does that easing of pressure and allowing of material to gestate compensate for what is lost, which is that in the old days you didn’t know what was going to happen next, and that every new record might yet change your lives with as yet unimagined success?

BA: There’s a trade off. The eventual realisation that you are not part of the mainstream anymore, as we clearly no longer are, does give you the freedom go to interesting places you could not always have gone to before. For me now the concept of a record has to be very strong to act on it, and I won’t start writing simply because it is time to release a record again. For example, the material and ideas I thought would be perfect for A New Morning, were actually followed through on and became The Blue Hour sixteen years later. Trying to carry them into the songs I was writing at the time, and make a record about the darkness of the countryside when you want your songs to be rotated on Radio One, was never going to happen. And that’s one of the beauties and consolations of being set adrift from the mainstream, which is that you really don’t need to worry anymore about a particular kind of career path anymore. We’re never going to latch back onto the mainstream again, I know that, because we could make the greatest record we’ve ever made, or has ever been made, and we would still never be on Radio One again. And I’m fine with that now. I am a 52-year-old man, do you know what I mean? Age has got to give you something, because otherwise there is a part of you that might never get over what it has to teach you.

You plot your changing relationship with your fans from a high of believing you were in it together, to the low of seeing graffiti left on your street with directions to your house and a request to kill your cat. The lesson that fans live for you when they should be living for themselves, and that you should be living for yourself and not them, seems hard earned on both sides, particularly as you write about how much owe them for putting you where you wanted to be in the first place.

BA: It’s a fascinating process with fans, you were there in the early days, and you know that insane dynamic where the fans are still part of the experience. We used to hang out with you guys and it was like being with your mates where you share the same passions and interests, but then you get to that point in a band where the doors come down, and there is a separation where you find yourself either being mobbed by people or sitting on your own in an empty dressing room with no in-between. Life becomes polarised between these two extremes, and it is unavoidable because it is built into success, and so to some extent, is no more than what you wanted and signed up for, but there is that lovely point when you first start when the people who follow you aren’t an abstract, “the audience”, but friends, and there is something special about those days I wanted to capture in the book. Because those days were really important, one of those lovely periods you can never have back or go back to again.

After that you become public property, where you have an image you keep up to avoid disappointing people, and where everything you say is taken at face value. Like the story you mention in the book where I forget that I asked a couple of fans to come back to my house in two days time, only to be polite, then completely forgot about it, and ended up instigating a campaign of abuse against myself…

I understand the danger of taking rock stars at their word. In early 95 I bumped into you at the Severn Bridge Services and you told me that I should join you in Watford in a week, where you would meet me outside the venue and let me into a gig!

BA: Oh no, you’re joking…what an invitation! My God, and did I do it?

I would love to have said you did! I still got in, so no hard feelings.

BA: I’m so sorry! What you’ve got to understand is that in a band when you meet someone at the services you always want to leave the conversation on a high note, to contrast with the surroundings, hence the Watford Colosseum! I just hoped that you wouldn’t believe me and would realise that in the end it was all just…words!

Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn is out now via Little Brown