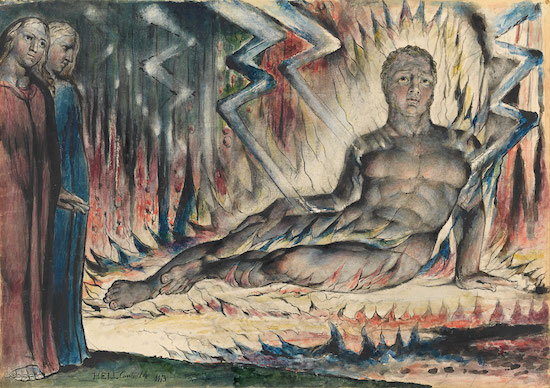

William Blake (1757-1827) Capaneus the Blasphemer 1824-1827. Pen and ink and watercolour over pencil and black chalk, with sponging and scratching out, 374 x 527 mm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The eighteenth-century poet and painter William Blake was a working-class visionary genius who lived in near poverty and who critics dismissed as an “unfortunate lunatic”. He had zero time for the bullshit of his day and, as a result, he makes an admirable role model for artists in all media. Blake stands as unshakeable proof that art is not what the chattering classes believe it to be.

Blake’s words to the hymn ‘Jerusalem’ have become the unofficial English national anthem, belted out with gusto by the flag-waving patriotic crowd at the finale of the Last Night of the Proms. The hymn’s establishment credentials are strengthened through its adoption by the English cricket team and the Women’s Institute, and its words were used by the post-war Labour prime minister Clement Attlee, one of the creators of the NHS and the welfare state, to describe the vision of Britain he was trying to build. Yet Blake is just as likely to be championed by anti-establishment figures such as Allen Ginsberg, Patti Smith or Billy Bragg, or played by colliery brass bands in solid working-class areas. What other artists can boast claims by both the establishment and the counterculture like this?

There are many ways that musicians can be inspired by Blake. Here are five examples of the different approaches available.

Julian Cope – ‘Psychedelic Odin’ (2008)

Julian Cope’s ‘Psychedelic Odin’ is a perfect example of someone using Blake as a starting point in order to get a headful of hog-wild ideas and then go off on one.

The first couple of minutes of this song are based on the first three stanzas of ‘The Little Black Boy’ from Songs of Innocence. Cope is a child at his mother’s knee (having changed Blake’s words so that it is no longer an African mother teaching him about the warmth of God, but a European one). In the next verse he adapts those stanzas further, substituting a cruel father for Blake’s loving mother and a dying god for a living one. It’s interesting stuff, but the song is only half done and it doesn’t quite prepare you for where he is headed.

The next verse moves us to heathen moon worship, but that’s still not weird enough for Cope. For the last section of the song, he adopts a creepily deranged singing voice and claims to have become the Norse god Odin himself. He then stands in a foreboding northern landscape while river spirits order him to kill all the southern Gods, a mission he is entirely on board with. This is, clearly, quite some journey from Songs of Innocence. You are left wondering quite how he made the leap from Blake’s comforting children’s poem to god-on-god deicide.

Still, William Blake would undoubtedly have approved of how Cope ends the song – with a chant of “The true fiend rules in God’s name!”

Johanna Glaza – ‘Albion’ (2018)

Musicians inspired by Blake often struggle with the question of how to update his material to make it more palatable to a modern audience. Blake’s words are a form of proto-romantic Gothic melodrama that were considered old fashioned even as they were being written. What is the best way to make them relevant to the contemporary world?

The best results usually come from ignoring this issue entirely. If you recognise something of value in his work, then just trust that others will see it also. That stranded-out-of-time aesthetic is easier to embrace than fight against. A perfect example of this is the title track from Johanna Glaza’s recent EP Albion – it’s your loss if you’re not on board.

Testament – ‘London (Blake Remixed)’ (2015)

That updating Blake is difficult is, of course, a good reason to do it. The gold standard is probably Testament, the North London-born rapper and beatboxer, with his Blake Remixed project.

Many of Blake’s early works were intended as songs. He put together words, images and music in a way that modern musicians take for granted, but which was incredibly ahead of the times for the 1780s. The melodies that he used have been lost, unfortunately, although there are accounts of him having a good singing voice. Testament’s work reminds us that, with Blake’s confidence, certainty, hunger for a fight and lyrical genius, he would have been absolutely brutal in rap battles.

Bruce Dickinson – ‘Book of Thel’ (1998)

Although being respectful to Blake can work wonders, it is also entirely acceptable to just scavenge scraps from his mythology and playfully muck around with them.

Much of Blake’s work doesn’t really take place in linear time as we understand it. Instead, events are understood to be imminent, to have already happened and to be constantly happening at the same time. Different versions of his longest illustrated work Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion come with the pages in different order, and it doesn’t seem to make much difference. As a result, just letting Blake wash over you is as much a valid approach as deep, rigorous study.

This is the approach that Iron Maiden’s Bruce Dickinson took on his Chemical Wedding solo album, which featured Blake’s artwork and a triptych of songs inspired by him: ‘Book of Thel’, ‘The Gates of Urizen’ and ‘Jerusalem’. ‘Book of Thel’, in particular, has absolutely nothing in common with Blake’s work of the same name. Dickinson is just enjoying the imagery, and why not? For all that Blake is associated with classical music and the Last Night of the Proms, his horrific heightened mythic melodrama is much better suited to heavy metal.

Dickinson’s playful misappropriation does not mean that he doesn’t have a good understanding of Blake’s work. He wrote new music for Jerusalem because he thought the nationalistic air of Sir Hubert Parry’s hymn Jerusalem, now the unofficial English national anthem, was at odds with Blake’s meaning. In this, Dickinson was more astute than many.

Chemical Wedding is generally considered to be Dickinson’s best solo work and there is a body of thought which claims it is better than anything he has done with Iron Maiden. This talk is heresy and must be brutally silenced before Steve Harris hears of it.

Fat Les – ‘Jerusalem’ (2000)

William Blake is such a complex and multi-faceted artist that it’s hard to say that anyone’s take on him is wrong. A million different perspectives on his work produce a million different interpretations, all of which will have their own unique validity. The only exception to this rule is the single ‘Jerusalem’ by Fat Les, which is so wrong it hurts.

This was a football single released in the dark years of the Britpop hangover by Keith Allen, Michael Barrymore, Damien Hirst and the cheese guy from Blur, complete with a military drum beat and chants of “England!”

A central figure in Blake’s mythology is the complex figure of Urizen. Urizen symbolises the reasoning part of the mind and much of Blake’s work is about his failings and his limits. Urizen shrinks and encloses our world, and elevates his own sense of importance until he has falsely convinced himself that he is god. Urizen, in other words, is cocaine in symbolic form. To be coked up in the Britpop 90s was to be profoundly anti-Blakean, and entirely blind to the extent to which you were missing the point.

With hindsight, the real horror of this song was the blueprint its video gave to the advertising industry. It featured choirs of children, laddish football fans, gospel choirs, public schoolboys and a smattering of minor celebrities, all pulling together in some forced common goal. This model has since become a standard tool used by phone companies, broadband providers and other corporate entities when they wish to hijack our sense of geographical identity for their own ends.

We shouldn’t blame William Blake for this. When you can see all Eternity in front of you, it is easy to overlook Damien Hirst and Keith Allen.

The Pet Shop Boys did a remix of this, incidentally, but I don’t think they spent very long on it.

Frank Turner – ‘I Believed You, William Blake’ (2019)

A final approach to Blake is to ignore the work and write about William or his wife Catherine instead. Catherine was deeply loyal to her husband throughout her life, enduring poverty and illness to support him in his work. She acted as an assistant and coloured a number of his prints in watercolour. She has become something of a mythologised figure in recent years, so it can be easier to lose sight of the real woman, but Frank Turner’s beautiful song ‘I Believed You, William Blake’ captures her humanity better than anything else I’ve read or heard.

In Turner’s telling, Catherine’s only ask is that the person she gave her life to, who claimed to speak with angels and live in Eternity, was telling her the truth and would not leave her at the end of their lives. This is a great, universal desire – that the thing we devote ourselves to is worthy of our devotion.

William died before Catherine, but she said that his spirit visited her daily, and that they conversed at length about matters mundane and divine. Catherine never stopped believing in her husband, even after death. William Blake and his work were a gift worthy of Catherine’s devotion, which for my money makes it worthy of the attention of musicians also.

—

William Blake Now: Why He Matters More Than Ever, by John Higgs, is published by W&N. Higgs will be at The Social, London, for the launch of his book on Monday 18 September. He will also be taking part in a panel exploring Blake’s legacy at the Tate Britain on 31 January 2020. The exhibition, William Blake, will be at Tate Britain until 2 February 2020