It started in the throat. There was a period in my life where I couldn’t bring myself to swallow solid food. I’d put food in my mouth and chew, move it around my mouth, from left to right, occasionally sucking the juices from it. I sucked on crisps, meats, potatoes. I could swallow gravy, soups, orange juices, water.

I became thinner and thinner, until a large knife cleaved my body and mind clean in two. I was at war with my own body, in its jail, screaming at myself to stop this shit, punching myself in the head.

I was a monster. My head looked like a huge strawberry on a cocktail stick neck. My wrists looked like two cocks and my chest was dented and yellowed. My mouth was filled with ulcers, some the size of a pea. My mother would buy steroid creams to try and stop them. She even tried to “sugar bomb” my food when I wasn’t looking, anything to keep me going, to keep me alive.

I grabbed myself by the lapels and interrogated my body.

Oliver 1: How big are your wrists?

Oliver 2: Not any bigger than last time.

Oliver 1: Okay, but what about your arms? How are they doing?

Oliver 2: Not fatter, if that’s what you’re getting at.

Oliver 1: How about your cock?

Oliver 2: Let me just grab that tape measure…

I’d speak to myself, draw outlines of my cock on pieces of paper, then put one piece of paper over the other. Had it grown? Truly, it was the mind of a young man. I stood on scales. I put the scales on uneven wooden floors, tried to trick my own brain that I was putting on weight, that things were getting better. They weren’t. I printed pornography out on colour printers. The printers would always run out of ink, leaving me with legs and feet, breasts and cocks, veiny ankles, collarbones, tater-tot nipples, withered-star assholes, mouths.

I began drawing. I’d buy gel pens and would draw the body coming apart. The body was something to be exploded into pieces, sawed up. It was my version of dissection. I was a Vesalius with a gel pen, a Galen with a penchant for decapitated bodies. I’d draw hundreds in a month, hundreds of A4 illustrations, all blood and flesh.

Here’s one where a foot-long wiener has speared a man’s ears. His skull has erupted with a volcano explosion of blood and he has, oddly, a hole in his torso exposing his heart.

And here’s a part where a shotgun has blasted somebody’s face out the back of their head. Also note the flying sausage in the top left and a severed cock just below.

Every day I thought about my throat, that something was stuck in it, that a piece of food was lodged in it and preventing me from breathing. The throat is a claustrophobic place, a tight entrance to the cave that is the body.

It’s this closeness and this claustrophobia that led to horror films. I watched bodies being torn apart with perverse fascination. The narrative didn’t matter because I wasn’t looking for story: I was looking for the repeated body, the body paused, the body forward-winded and re-winded. I wanted to see the gore on cathode ray tube televisions. There was something better about seeing blood and bodies paused on a videotape, the streak of white noise like a censor across the middle of the screen.

I’d watch Day of the Dead (1985) again and again, but never for the story. I’d forward-wind to see the orgy of violence at the end, heads being torn off and bodies ripped in two. The guts trailing down the bunker hallway, intestines being chewed on.

There was, to me, no narrative. These images, I’d pause them and press my face to the television screen. I was looking for myself in the blood and guts, I thought. I was the anatomist cutting up the body, dissecting films.

I eventually began to gravitate towards characters like Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver (1976) or Seth Brundle from The Fly (1986), men who were, in their own way, deconstructing themselves, breaking themselves down, undoing the jigsaw that was their bodies and laying it out on the table.

Brundle, when asked if he’s a bodybuilder, answers “Yeah, I build bodies. I take them apart and put them back together again.” Even Bickle, god’s lonely man, experiments with his body. “Total organisation,” he says. “Too much sitting has ruined my body. There will be no more pills, no more bad food… Every muscle must be tight.”

Bickle’s idea of ‘total force’ – to destroy Palatine, is also a plan to destroy himself. “All the king’s men cannot put it back together again,” he says at one point. His body is honed throughout the film and I remember watching the prison of his apartment, the control Bickle had that, to me, had all the violence of the horror films I was obsessed with. His body, sculpted, made me think of those anatomical figures in Vesalius’s illustrations; he just hadn’t been cut open yet. It was this idea of routine and transformation that interested me most about Bickle. The dedication to his routine, the training and isolation. Push ups and pull ups. Drawing the gun in front of a mirror, repeatedly pulling the knife from his boot.

In Bickle, I saw a little part of myself, the obsession of pausing and playing the videotape, of drawing the same pictures over and over, of eating tomato soup twice a day every day for over 5 years. This was my version of pulling a knife from the boot. These routines were my pull ups, my push ups. I knew that every day I wasn’t eating was a day where I was destroying my body. I truly attacked it with ‘true force’ – all the king’s men, I thought, would never be able to put me back together again.

And then, as we reach the climax of the film, Bickle destroys other bodies and, at the same time, allows his to be destroyed. I’d watch this ending again and again, rewinding it and playing it again. I’d pause on Bickle blowing somebody’s fingers off, on the bullets peppering another man’s face with bullets, a knife through the hand. It’s pure horror.

Just like the horror of the bodies, there was the horror of place here too. In that final scene, I became obsessed with that tenement. Those dark mustard walls, thick with paint, graffiti. The brown of the front door, the dimness of the lights inside. The New York of Taxi Driver was a New York of welfare hotels like The Martinique. Built in 1897, its guests all shared something in common: wealth. The decline started in the 70s. The city started renting rooms as emergency housing for the homeless and it was then that the hotel assumed the identity most New Yorkers know it for – ‘as the most notorious of several crime-infested depositories of poor people known until the end of the 1980’s as welfare hotels.’

The New York tenement, to me, is a throat. The tightness of those corridors, the stairwells.

A lot of my favourite films all take place in what I like to call throats. The Thing (1982) is a great example of those enclosed spaces, a film of corridors and flesh and paranoia. John Carpenter’s film spoke to me at a young age because I didn’t know what was inside of me. There was something in my brain telling me not to eat, to destroy my body. I was The Thing, but my body was also the location of the film, too: empty corridors, a place of destruction.

But the place where I really lived was Wolverhampton. I don’t remember much about the city because there wasn’t much to remember. During those years, everything seemed grey. I was, as I mentioned earlier, a monster. In my mind, I was The Thing, a thing to be humiliated. It felt that way. One girl once called me the ugliest boy she had ever seen. Another promised to give me a kiss on the cheek if I bought them a chocolate bar from a vending machine. I did. She got the chocolate bar; I did not get the kiss.

I felt a lot of my life took place in that bedroom, on that television in my room. I would go to bed starving every night and cry myself to sleep. The house where I became ill still comes back to me, in dreams. I dream that I have murdered somebody and buried it at the bottom of the garden, beneath a rhubarb patch. I sit in the kitchen and I can smell the rotting of the corpse. I see everybody looking at me as if they know I’ve done something wrong, so I get up and go to the bottom of the garden. How often do I have this dream? Every so often. But every time I do, I wake up thinking that I truly have murdered somebody and that I am guilty of something. I walk down the garden and my pace slows down. I don’t want to look. But when I get there, the hole has already been dug for me and in that hole is the corpse. It’s hot out in the garden and the corpse still has flesh on it. It looks like pork fat, hanging off those cheek bones. There’s a mop of hair on the skull still. I dig down and take a look at the corpse. It’s me. It’s always me.

I wonder if I introduced a bearded Sigmund Freud to this piece, whether he’d like to say a little something of my dream. I wonder. But this piece is no place for Freud, and I don’t care for the interpretation of a dead man either. I was around eighteen when I was ‘better’ again and by ‘better’ I mean I was chewing and swallowing food. I still had panic attacks. I was still woken up by those dreams. I refuse to call them nightmares, don’t ask me why. A little part of me had died in that house and whenever we drive past it, I feel there really is something buried at the bottom of the garden. It’s chilling. The house, I believe, is haunted by that older version of me. In the dark, I stare up at that middle window that was my bedroom and there is a silhouette of my younger self, rake thin and hungry, staring back at me. He says nothing. I don’t say anything either.

But there’s something to be said of that room. It’s where I learned about my body. Those films were my school, my solace, my church. It was, in many ways, through violence and decapitation and murder and guts and brains and eyeballs and cocks and vaginas and rotting corpses that I learned to love those around me and love myself just a little bit more.

And this brings us to the book. I wrote half of this in London, half in Las Vegas. It was in Las Vegas that I had the idea to bring it together into a book. It was around 40 degrees a day there. I was staying at a place called the Tahiti Lodge by the Orleans casino. I’d shaved my hair to a grade two and bleached it blonde. I was going through some sort of life crisis, it seemed. I was smoking marijuana often and drinking a lot more often. I went to New York, New York and watched two fat men play duelling pianos. I tried to crash a woman’s wedding party. I would go to Denny’s because it was 24 hours and write until 1am, 2am, 3am. I’d go back to my room. I was struggling to eat at the time. I don’t know why, so I was drinking. Boo hoo. But the book was born from this table in Denny’s. A spectacular place for it to be conceived too. In my exhausted, sometimes drunken state, I’d dream of those bodies I’d seen in films again. I became conscious of my own body again. I watched other people, watched them closely, their movements, the stupid mechanics of it all. People in the Golden Nugget with oxygen tanks next to them. The frenzied man who started doing one armed push-ups and then got his penis out at a group of kids. At the top of the Mirage, invited in by a stranger, to see the volcano erupt below us from their bedroom window.

The characters in the book are a car crash of tenderness and violence. They’re born from the things seen in those teenage years, the fragments, the body parts. Sometimes, I even struggle to give characters names because I feel it would cheapen the character. They exist very much in this world, but the places are nameless too. They’re part of some sort of Beckett-like landscape, a sort of everywhere and nowhere. A lot of my favourite writers – Grace Paley, Flannery O’Connor, Amelia Gray – all infected my writing. I like that. Infection, the noun, bad; infectious, the adjective, good. I found their writing helped give the violence and bluntness some degree of feeling in the book.

I’m writing this in a Hampton Inn in Las Vegas, Nevada. It’s 40 degrees and my skin is burnt. I’ve been out in the desert for a few weeks now and from here, I can see the mountains. The sky is purple. Everything is vast here, but it’s still a throat.

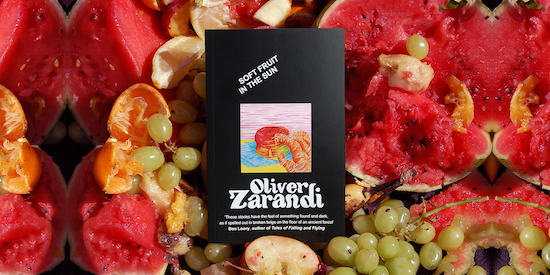

Soft Fruit in the Sun by Oliver Zarandi is published by Hexus Press