Leningrad, early 80s. A group of friends, musicians, and “worshippers of the West” are riding a train, strumming a guitar and mumbling English lyrics. A fellow passenger and upstanding USSR citizen stops them, accusing them of being traitors, enemies of the country. The singer responds “I’m a punk”, which doesn’t work with the policeman who intervenes and instructs him to get off the train. To shut up his protestations, someone punches the Punk in the face, leaving him on the floor with a bloody nose.

This is where Leto (directed by Kirill Serebrennikov, under house arrest from August 2017 to April 2019 under charges that his supporters consider to be fabricated, in order to censor his often political work) transforms from a straightforward biopic about the Leningrad rock scene into an outright musical, and a fantastical celebration of creative freedom. The Punk, lifted from the floor by a mysterious narrator-type character, starts performing Talking Heads’ ‘Psycho Killer’. It’s a punk rendition, alright: the familiar, neat beat gives way to a faster, messier arrangement, with all the instruments playing over each other, and above all, the Punk’s vocals trying to imitate David Byrne’s inflection with a heavy Russian accent. The visuals follow suit, as the crisp, somber black and white gets literally scribbled over with song lyrics, doodles and blotches of colour as the camera follows the Punk and his friends wreaking havoc across the train. It’s a near-perfect musical moment: one of our heroes picks himself up after being scorned, teaches his offenders a lesson by demonstrating the greatness of Talking Heads, all the while making it impossible for the viewer not to smile and tap their feet to the contagious energy of the sequence.

It’s common practice for the movie musical: we know it didn’t happen, it couldn’t happen, but reality-bending is an inherent feature of the genre, and those who enjoy musicals are ready to sacrifice naturalism to experience the sheer pleasure that comes with a good fantasy sequence. It’s wish fulfilment at its finest. The viewer makes a pact with the filmmaker: you’re both going to put reality aside for a few minutes, see what you would rather see happen while hearing the very greatest tunes. No questions asked. However, this form is less often developed through punk music, or rock and roll ideals. Leto is, in fact, a stranger creature than a glitzy musical or a straightforward rock biopic: it’s a genre-bending combination of the two that plays with the conventions of both archetypes, and uses them to integrate its subject.

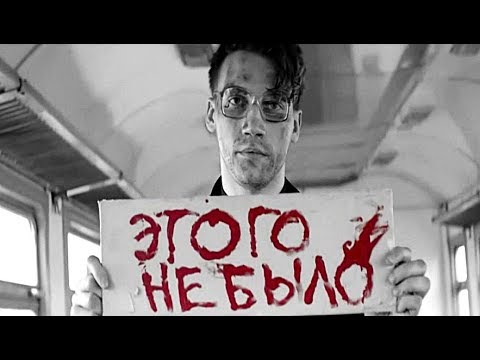

At the end of the glorious ‘Psycho Killer’ scene, the same character who introduced the number shows up with a sign that reads “This didn’t happen”, thus breaking the musical filmmaker/fan rule: we know it didn’t happen, but that doesn’t mean we want to be reminded of it. The abrupt return to reality makes the captive audience feel cheated and sad (remember the ending of La La Land?). So why does Leto keep breaking the illusion, with a character referred to as “The Skeptic”, over and over again, after all the best musical sequences in the film?

Leto follows the real-life events that led to the formation of the band Kino, headed by Viktor Tsoi (played in the film by Teo Yoo), under the mentorship of Mike Naumenko (Roman Bilyk), leader of the already established rock band Zoopark. These and similar bands, born out of admiration and often imitation of Western rock acts, were given a dedicated space to perform in the Leningrad Rock Club, established in 1981 and overseen by the KGB, who instituted a commission to review and approve all songs and lyrics prior to the inclusion of every new act. This, of course, put a severe limitation on the freedom of expression these songwriters had: they were encouraged to sing about “social issues”, but with no mention of politics and strictly no sex. Moreover, the performances themselves had to be controlled and subdued to avoid any chaos, resulting in an atmosphere that the film renders as the one you would expect at the Royal Albert Hall, rather than, say, Ally Pally.

Under these circumstances, the energetic and innovative young musicians featured in Leto had to constantly stifle their ambitions and impulses, resorting to living their rock and roll dreams only in the space of their collective fantasy. In this sense, the film works at times like some kind of piece of revisionist history, allowing the artists to explore the freedom they craved only in the space of a musical number, before readily returning to reality. Leto, then, uses an element of the movie musical, the fantasy sequence, then negates it to reflect the incompatibility between reality and reverie. This harsh limitation on wish fulfillment tinges the film with an atmosphere of melancholy and nostalgia: despite the success that both Zoopark and, to a larger extent, Kino achieved, the viewer becomes painfully aware of the divide between their ambitions and the actual facts of history.

The film ends with a performance by Kino at the beginning of their rise to fame, but the final shots of Tsoi and Naumenko are subtitled by the year of their death: 1990 for Tsoi, 1991 for Naumenko, just before they could experience the dissolution of the USSR. This bittersweet ending omits most of Kino’s career, including their unanimous fame that ended up reaching the West, and their tours that quickly travelled far beyond the Leningrad Rock Club. But despite the progressively looser limitations set by the KGB, their work, as became the case for all other state-approved rock bands, was always subject to government approval. And isn’t that the opposite of what rock and roll stands for? Doesn’t KGB-pleasing music go against the Punk’s challenge to authority, Mike’s guitar-smashing fantasies, and the freedom of using rock to express sincere, unfiltered feeling?

Serebrennikov’s handling of this piece of musical history, then, offers a deeply romanticised account, filled with genuine love for its protagonist but also imbued with a sense of regret. “This didn’t happen”, in this case, extends to what could have been in a different, freer context, and never was. The filmmaker captures these bands in a state of grace, where their blossoming energy and creativity feed off one another, and contribute to the brief illusion that anything is possible – maybe even convincing upstanding, law-abiding comrades to sing along to ‘Psycho Killer’. Leto, romantically and mournfully, answers the question: “This didn’t happen. But what if it did?”.

LETO is in cinemas from 16 August and streaming on MUBI