For the latest instalment in our occasional series of Quietus writers’ charts, we asked our network of beloved scribes to tell us of a song that acted as a gateway drug – a cover version that led them to the original, and in turn introduced them to that artist’s wider discography.

Please note that this is not a list of The Quietus’ favourite cover songs. Let’s be honest, Muse’s butchering of Nina Simone’s ‘Feeling Good’, or The Futureheads’ happy-go-lucky take on Kate Bush wouldn’t feature in a list like that. Rather, what you’ll find below are 40 tales of how a cover version, good or bad, took one of our esteemed contributors to a new musical world. It could be the revelation of a pathway, from your favourite band to your favourite band’s favourite band (who then becomes your new favourite band), or it could just be that wonderful feeling when you realise that you’re only scratching the surface of what’s out there to explore.

Read on for our list, which is in no particular order, was compiled by me (Patrick Clarke), and features contributions from Kiran Acharya, Jeremy Allen, Aimee Armstrong, Matthew Barton, David Bennun, Brian Coney, Lara C. Cory, John Doran, Priscilla Eyles, Richard Fontenoy, Diva Harris, Tom Huddleston, Sean Kitching, Adrian Lobb, Dorian Lynskey, Julian Marszalek, Suzie McCracken, Ned Raggett, Jude Rogers, Barnaby Smith, Adelle Stripe, Luke Turner and Ian Wade.

Love via The Damned – ‘Alone Again Or’

You can blame The Young Ones. Episodes ended up in America on MTV in the mid to late 1980s, and I caught the one with the Damned in 1987. Their two-disc The Light At the End of the Tunnel compilation had just been released, I picked it up and loved it. They had a slew of covers, but ‘Alone Again Or’ really stuck with me, just the way that ringing guitar line went, the trumpet, the whole thing. Some years later I finally heard Love and things made even more sense, and hearing their original playing out this year at the end of series one of Russian Doll was just the latest amazing moment with ‘Alone Again Or.’ But I needed Dave Vanian and company to take that first step. (And Rik and Vyvyan too I guess.)

Ned Raggett

Brian Eno via The Creepers/Bauhaus – ‘Baby’s On Fire/Third Uncle’

I’m not a gambling man but I’ll lay money that if my learned colleague Luke Turner has authored one of these capsules then it will refer to the fact that he didn’t have much access to contemporary music as a kid due to his parents’ religiosity. I say this because I had a similar experience thanks mainly to my Dad (who wasn’t a member of the clergy but was very puritanical for a strict Roman Catholic). This type of anti-TOTP/Radio One upbringing plays temporal havoc with your education in pop culture. I’ve always found the Ramones and Sex Pistols slightly silly, simply because I heard Napalm Death and Minor Threat just before them. But certainly I had no grounding in any kind of musical canon at home and pretty much had to invent my own during my teenage years. After synth pop my first real passion was for post punk and the many cover versions this genre presented me with was the first bit of evidence I encountered that punk hadn’t been some bolt from the blue but music that stood on a continuum.

Some of these covers were purposefully challopsian such as the Sisters Of Mercy versioning Hot Chocolate’s ‘Emma’ or Dolly Parton’s ‘Jolene’, while others spoke directly to where they were coming from (The Rolling Stones’ ‘Gimme Shelter’ and The Stooges’ ‘1969’). A long time has now passed since I considered the Eldritch versions to be the superior documents but that doesn’t mean my revisionism goes right across the board. I had been listening to ‘Baby’s On Fire’ by The Creepers (Marc Riley’s post Fall outfit) and ‘Third Uncle’ by Bauhaus for years before I realised I was actually listening to the work of Brian Eno. In my defence, pre-internet, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) and Here Come The Warm Jets weren’t albums you stumbled across every day but by the time I did, I was hooked in to the cover versions for keeps. I appreciated the fact that they looked back to an incredibly fertile elevated period of post-glam pre-punk pop experimentalism but I also appreciated the fact they’d been supercharged with amphetamines and low grade acid for the grottiest of dancefloors, emitting a powerful primal echo that still reverberates strongly for me today.

John Doran

Michael Hurley via Vetiver – ‘Blue Driver’

Last year I saw Michael Hurley play at a small house concert where absolutely nobody knew he was – he was the support act. After the show, I went up to him and told him about how I came to his music through Andy Cabic of Vetiver. Hurley, now 77, is not what you’d call a verbal communicator and he replied with just a head nod and an ‘oh yeah’. But it was true: through Cabic’s persistent championing of Hurley, and his cover versions of several of his songs, I became thoroughly converted to this so-called ‘outsider’ musician. ‘Blue Driver’, from Vetiver’s 2009 album of covers Thing of the Past, was the decisive factor: a fairly faithful, no-frills version of this track from Hurley’s 1972 record Hi Fi Snock Uptown. Given his impassive reaction that night, I’m pretty glad I didn’t go into that much detail with him.

Barnaby Smith

Bruce Springsteen via Frankie Goes To Hollywood – ‘Born To Run’

I mean, I’d heard of Bruce Springsteen. He’d released a fair bit by 1984 – in fact he was fast becoming quite a massive deal during that year – and I recalled the odd single like ‘Hungry Heart’ on a chart rundown, but I’d not heard ‘Born To Run’. So when the Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Welcome To The Pleasuredome opus came along with it on, it became the doorway into Bruce, and an appreciation of his catalogue that peaked with an eventual soup-based epiphany to Nebraska. It made him feel a bit exciting and to be honest, I still think this is the better version, especially with the Brookside sample at the end of ‘Fury’ running into it. So thank you, Frankie. Not only had they tutored me in the friskier elements of gay sex and the devastating impact of nuclear warheads, they got me into Bruce Springsteen too. HA!

Ian Wade

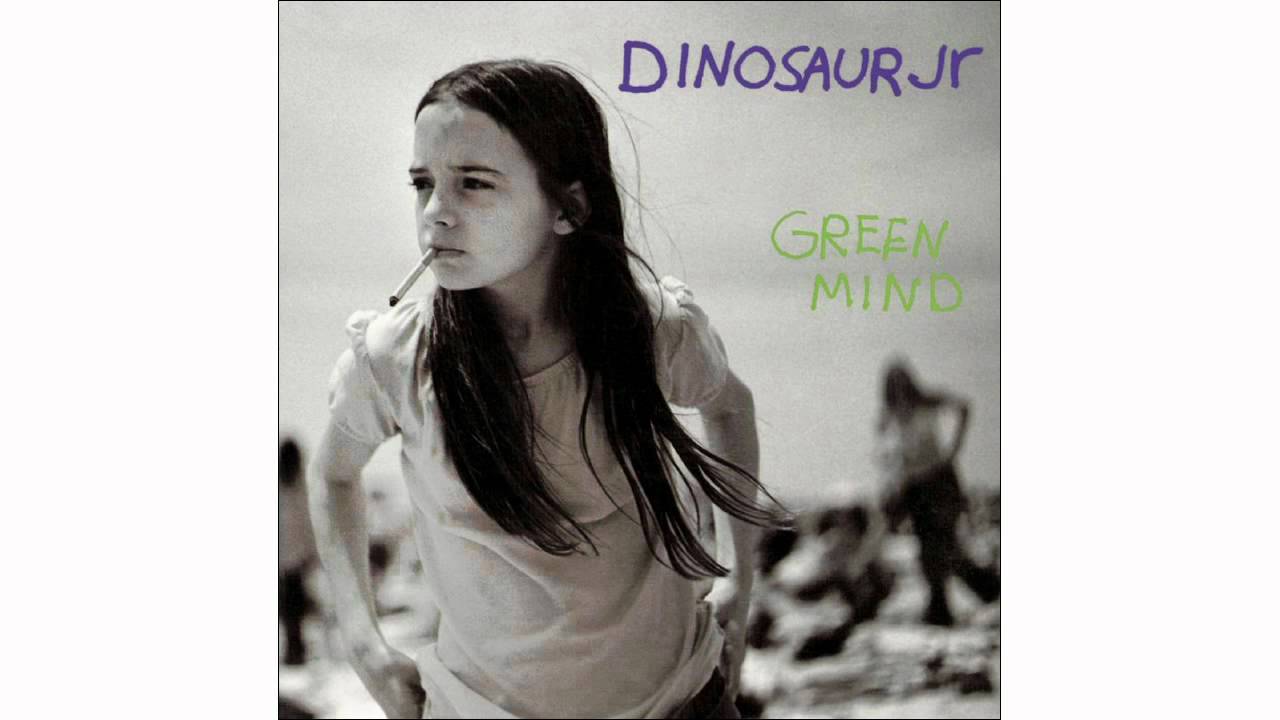

Gram Parsons via Dinosaur Jr. – ‘Hot Burrito #2’

It wasn’t so much Dinosaur Jr’s crunchy, howling take on The Flying Burrito Brothers’ ‘Hot Burrito #2’ – issued as the B-side to Get Me in 1992 – that put me on the trail of Gram Parsons. It was an interview J Mascis gave to the NME around the same time, in which he spoke with frankly un-J-like enthusiasm about Gram’s work, revealing that he’d initially considered covering ‘Hot Burrito #1’, only to discover that it was too emotional to even attempt. This idea – of a song so heartbreaking he couldn’t bear to sing it – was the one that sent me out searching for The Gilded Palace of Sin, sparking a love of Gram, and country rock in general, that’s never wavered since.

Tom Huddleston

Kate Bush via The Futureheads – ‘Hounds Of Love’

When, at the age of 13 or so, I heard The Futureheads’ version of ‘Hounds Of Love’ it was obvious there was something very different about that song compared to the rest of their passable indie pop. When I found Kate Bush, that jump in quality suddenly made sense. The Futureheads’ version is a cut above their other songs, but when I heard the original it was transportive, plunging me into a world of bottomless passion, melodrama and romance unlike anything an indie also-ran could even imagine, and then on to the rest of that singular discography. It just goes to show that even the cringiest of covers can send you down the most beautiful path.

Patrick Clarke

Leonard Cohen via Nick Cave – ‘I’m Your Man’

Nick Cave has faced many comparisons to Leonard Cohen, not least by me (sort of). It’s of course a little lazy, but there’s something there – a shared genius when it comes to handling darkness with tenderness and care. It was Cave I got obsessed with first, and eventually found version of ‘I’m Your Man’. It isn’t a particularly special interpretation, he’s always been better when inhabiting the worlds he created himself, rather it was the sense of devotion with which he treated Cohen’s material, pointing me towards the man even he, to my mind a master, considers the greatest of them all.

Patrick Clarke

Serge Gainsbourg via Mick Harvey – Intoxicated Man

Mick Harvey, thanks chiefly to the key role he held in Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds is somebody I’ve long considered a godfather to that entire strain of darkly romantic, Europhile, suited-and-booted indie rock. But it wasn’t until I heard the first of what would be his quartet of Serge Gainsbourg English-language covers albums that I understood his own principal source of inspiration. Intoxicated Man (1995) was a revelation. Like all the best translations, its fidelity was artistic, not literal; sympathetic but not subservient. Having heard how bewitching Harvey made these songs for the Anglophone ear, I was able to able to go to Gainsbourg himself with a grasp of the latter’s rich originality. Meanwhile, the Harvey versions continue to stand up superbly in their own right.

David Bennun

Joy Division Via Therapy? – ‘Isolation’

The feeling of forced confession sits so well alongside Troublegum tracks like ‘Hellbelly’ (“Jesus without the suffering”) or ‘Turn’ (“Barging into the presence of god”) that it was shocking and almost disappointing to learn, aged maybe thirteen, that ‘Isolation’ wasn’t an original. And then to hear Joy Division and think ‘Isolation’ was a diminished, demo-like and antiquated thing. But this callow impression was eventually dispelled by the tempting, mesmeric bassline and Ian Curtis’ insomniac croon. For the first time there was a sense of emotional correspondence between real people and real places. A sense that beyond the morbid news bulletins of Northern Ireland there existed elsewheres – and that these places may not necessarily be kind.

Kiran Acharya

The Stooges via Sonic Youth – ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’

In a time before the internet and with no money, it was hard to have the means to do deep dives into back catalogues and supposedly seminal artists. Then again, were The Stooges quite the classic rock force they are now back in the late 90s? Sonic Youth I knew after seeing them circa-Dirty at Reading 1996, and it was after buying their 1983 album Confusion Is Sex second hand for a few quid that I first heard their howling, scratchy and feral ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ emerging out of the drones of ‘Freezer Burn’. It wasn’t as good as ‘Brother James’, like, but it meant that when, on a dancefloor at some point around 2000, I heard The Stooges original it was a strange experience, that massive riff giving way to a curiously jangling, monotonous song. That’s the thing with cover versions for me, often the thrill of hearing the interpretation first means that the original never quite lives up to that first experience. I mean, there’s no fucking way I’m going to get into Bob Dylan via Guns N’Roses ‘Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door’ now is there?

Luke Turner

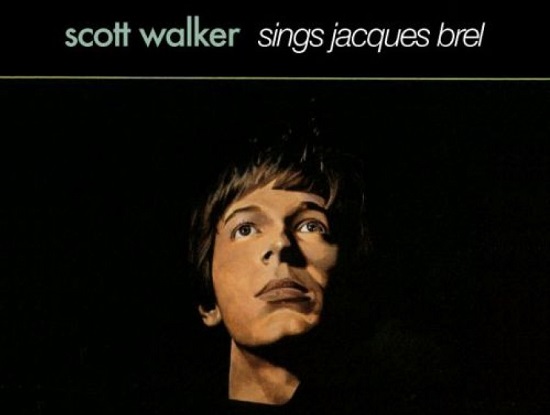

Jacques Brel via Scott Walker – ‘Jackie’

Scott Walker’s classic rendition of Jacques Brel’s song ‘Jackie’ (translated so cleverly by Mort Shuman) alerted me to both his and Belgian Brel’s unique talents. Comparable to fellow gallic singers Piaf or Claude Nougaro for sheer showmanship; listening to the original song ‘La chanson de Jackie’ it’s clear what a strong influence Brel was on Walker’s own commitment to the pure joy and theatricality of music and its ability to take you on an emotional journey.

Here was a song that made you laugh by singing about venereal disease and got awy with scandalously singing about ‘real faggots and fake virgins’ (of course not exactly politically correct now but refreshingly blunt for the time), and the travails of being young, cute and stupid with the world as your oyster. He embodied these songs and made you believe in them; even without knowing French their wistful emotional intent is clear, and it takes a singer of immense talent and commitment to that. Tragic he died so young aged 49, but his legacy lives in the dramatic flair of singers as diverse as Bowie, Walker, Marc Almond, Amanda Palmer and Andy Williams. Merci!

Priscilla Eyles

Jacques Brel via Scott Walker – ‘Jackie’

Like plenty of Anglo Saxons I’d assumed I knew what Jacques Brel sounded like, and funnily enough I was under the misapprehension it was a bit like Scott Walker: croony, baritone-y, soft as velvet… I picked up Les Marquises for €5 in a Brussels bargain bin on a hapless weekend sojourn to the Belgian capital, and I was in for a shock when I got it home. Brel was brutal, guttural, maniacal at times – and this on his most musically placid recording. I made my way backwards through his catalogue, transfixed, and eventually found his ‘Jacky’; ‘Jackie’ (with the ie) by Walker, is a well-upholstered and dashing rendition that’s infinitely superior. The rest of Walker’s versions can’t hold a candle to Brel’s originals though, a fact the great man would have probably admitted himself.

Jeremy Allen

Echo and the Bunnymen via Pavement – ‘The Killing Moon’

For years, I unduly resented Stephen Malkmus for Pavement’s cover of ‘The Killing Moon’. How dare they – how dare anyone – undo the crucial minor key thrust of such a singularly lugubrious song, in favour of something so carefree and major-key and droll ("Cucumber, cu-cu-cumber, ca-ca-ca-ca-cabbage")? With time, I strove to forgive and forget and move on. Eventually, I saw it for what it was: a tack-sharp subversion, where a straight, note-for-note mimeo simply would not have done. Either way, the band’s decision to tackle it for a BBC Radio 1 session back in 1997 would (not least with its inclusion on Pavement’s final EP, Major Leagues) introduce a whole new audience, myself included, to the majesty of Ian McCulloch’s original and the Bunnymen as a whole. All is forgiven, Stephen.

Brian Coney

Neil Young via The Mission – ‘Like A Hurricane’

The thing about being in your 20s is that 10 years ago might as well be 10 million years ago. So it was in the college days of the 80s that we sneered and chortled at our flatmate and his seemingly archaic tastes in what came to deemed “classic rock”. But the boot was soon on the other foot when he overheard us getting off on The Mission’s cover of Neil Young’s ‘Like A Hurricane’. Sneering and chortling back at us, he took us into his bedroom to play the original version from American Stars And Bars. We had to agree that yes, this was pretty good, and so began a journey through the past into Neil Young’s back catalogue.

And then we struggled to keep the return bout of sneering and chortling under control. Notoriously tight with his stash, we almost whooped when we accidentally found our flatmate’s gear when he went off for a slash during Neil’s heroic second guitar solo. And then replaced it with a piece of wood that was lying by his bed. Even to this day, it’s impossible not to have a Pavlovian response whenever Neil Young gets played. Which, one suspects, is just how Shaky would want it.

Julian Marszalek

The Bee Gees via Feist – ‘Love You Inside Out/Inside And Out’

I’ve been racking my brains for a selection that’ll earn me slightly more street cred, but also, that’s kind of my point. It’s all too easy to consign the Bee Gees to musical history’s cheese bin. Like the best cover versions, Feist taking ‘Love You Inside Out’ a couple of octaves lower, and giving it a bit of a laid back, smokey zhuzh, allowed twee indie teenage me – who somehow managed to form a large percentage of her music taste around iPod adverts – to appreciate the beautiful songwriting that lurked beneath the satin. I’m tempted to go as far as saying that not only did it open my mind to the genius of Gibb, Gibb and Gibb, but also, more generally, to disco.

Diva Harris

Nina Simone via Muse – ‘Feeling Good’

Besides the red pills and tyrannical epicness, Muse are a pretty cool band. Or, at least that’s what I tell myself when I try to justify my unconditional admiration of their early work and my guilty affection for their latter. My love of their music began in High School; ‘Plug In Baby’, ‘Supermassive Blackhole’ and ‘Exogenesis Symphony’ parts‘1’,’2’and ‘3’ all tickled my fancy. But my unwavering love for the supercool intergalactic space rockers was most prominent in Feeling Good – most famously recorded by Nina Simone. Although many find this a ‘feel good’ anthem and cover it accordingly. I found Muse’s rendition melancholic, as though the uplifting lyrics were willfully obscuring a haunting truth. Suddenly the “birds flying high” were a murder of crows and “the scent of the pine” was the stench of decay. I now associate this gothic feeling with Simone, although admittedly her music’s harrowing nature is not usually so vehemently disguised. However I must stress, I categorically do not believe there is an intrinsic link between Nina Simone and Matt and the lads. But they did manage to point my youthful self in the direction of the perhaps the greatest voice in music.

Aimee Armstrong

Peter Schilling via Space Lady – ‘Major Tom’

The inimitable Space Lady’s ethereal 1990 version of ‘Major Tom’ sparked a few subliminal memories when her Greatest Hits came out in 2013, perhaps from background teenage radio days. It hadn’t made much personal impact in the 1980s, but Space Lady elevated it to a higher plane of consciousness. Then the original turned up as the title music to Cold War DDR drama Deutschland ‘83, leading to an obsessive quest for 12” extended remixes, DJ sets at the Kosmische Club (it fitted right in, as expected); then came the sublime revelation that Plastic Bertrand had recorded a Francophone version. Time to entertain contemporary teenagers with their own Eighties’ enthusiasm; but sadly the rest of Schilling’s output never quite achieved that glorious pinnacle.

Richard Fontenoy

Jacques Brel via Scott Walker – ‘Next’

One of my mother’s greatest gifts to me was her record collection. It wasn’t huge, but she was a fan of Scott Walker and recommended that I listen to him following a particularly rude teenage tantrum. We didn’t have books in the house, but records provided an equally important education. The discovery of Scott 2, and his version of Jacques Brel’s ‘Next’, was a revelation; a portal that opened into another, far bleaker dimension. The lyrics “I was still just a kid / when my innocence was lost / in a mobile army whorehouse / gift of the army, free of cost” were my first taste of real poetry. Brel’s vile narrative exploded through my speakers in 1991, an H-bomb that changed how I considered music and poetry forever. The original, ‘Au suivant’, is a spitting, bitter punk tango that never fails to raise the goosebumps. But there is still no denying the power and ferocity of Scott Walker’s rendition. It arrived at exactly the right moment.

Adelle Stripe

The Stooges via The Sisters Of Mercy – ‘1969’

Though less celebrated than Neil Tennant or Morrissey, Andrew Eldritch likewise peppered his lyrics with clues for the curious: Dominion/Mother Russia alone gave me a Bob Dylan gag and a riff on Shelley’s Ozymandias. I also trusted his taste in cover versions. When the brutish simplicity and apocalyptic petulance of 1969 led me to check out the first Stooges album, my ignorant adolescent suspicion of classic rock was blown to bits. Even the Jesus and Mary Chain dug the Stooges and they hated pretty much everything. I covered 1969 in my short-lived sixth-form goth band The Doll’s House (So easy to play! So much fun!) but I suspect our version wasn’t such a persuasive advertisement for its gonzo thrills.

Dorian Lynskey

Loudon Wainwright III via Rufus Wainwright – ‘One Man Guy’

Rufus Wainwright’s cover of his father’s track ‘One Man Guy’ stood out strangely on his 2001 album, Poses – his second and arguably still his best. Here was this simply strummed, uncomplicated folk song amid Wainwright’s emerging musical ambition and flamboyance. Given the well-documented strains in the pair’s relationship down the years, Rufus’s version feels like both a tribute and a mild rebuke to his dad. Regardless, the song pointed me towards Loudon Wainwright III’s prolific career and his arch and self-deprecating songs. ‘One Man Guy’ originally appeared on his 1985 album I’m Alright, but I started with a cheap vinyl copy of the brilliant 1975 record Unrequited. This was actually appropriate, as the album contained a sweet-with-hints-of-resentment song about his infant son’s appetite for mammary nourishment, ‘Rufus Is A Tit Man’.

Barnaby Smith

Neil Young via Saint Etienne – ‘Only Love Can Break Your Heart’

It’s not that I’d never heard of Neil Young, he just seemed, well, very not me. A bit Q magazine, and a grizzled old whining hippy troubadour. So of course when Saint Etienne hovered into viewed and this became my most caned single of the summer of 1990 alongside My Bloody Valentine’s ‘Soon’, I thought I’d give him a go. Working in a record shop where we’d delve into the back catalogue on quiet afternoons, I popped on After The Goldrush and was smitten. Of course it lacked the impact, but it tapped into a warmer aspect that resonated with the dabbling with soft drugs, still having some semblance of hair and sunshine. By the end of that summer I’d bought the choice cuts on Warners’ ! range, such as Harvest and Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. When he came around to releasing his next new album Ragged Glory I had developed an appreciation and read up on him, and even bought the triple Arc Weld live album where one disc he’d basically recorded loads of feedback, impressed as I was that he’d taken Sonic Youth on tour with him. I didn’t go mad – I steered clear of Trans and some of the slightly shit anti-MTV eighties gear – but then one badly lit post-pub session, I heard On The Beach, and realised he was fucking brilliant, and years later shortly after losing two close friends, I turned to the title track on repeat. So yeah, I didn’t need everything, but for Goldrush, On The Beach and Nowhere, I’d – to cop the modern parlance – properly ‘stanned’ for them.

Ian Wade

Italo Disco via Pet Shop Boys – ‘Paninaro’

This is not so much a cover version, more an eventual connecting of the dots. I knew that the Pet Shop Boys were dead keen on Italian disco, but when researching a piece I was writing a couple of years ago, I came across an old interview where Neil Tennant had mentioned that ‘Paninaro’ was something of a homage to the unhipper end of Italian disco and told Record Mirror that “Often the lyrics are very banal, there’s this great one called ‘Capsicum’ that’s a green pepper isn’t it? And the chorus goes ‘Capsi capsicum oh woah oh’. That is brilliant. The banality of them often makes them strangely moving, somehow.” I knew Italo stuff such as the latter half of the decade’s crossover hits like Starlight’s ‘Numero Uno’ and Gino Latino’s ‘Welcome’, but it was the slight melancholy and not-properly-translated end of the early eighties stuff that I was unaware of. Soon I’d fallen into an internet hole where I’d discovered the joys of Charlie’s ‘Spacer Woman’, Klein & MBO’s ‘Dirty Talk’ and started following an Italo Disco bot on Twitter which posted various bits and pieces like Azoto’s ‘Soft Emotion’ and Gay Cat Park’s ‘I’m A Vocoder’ which just sounded brilliant, and started harvesting these wonky, left-against-a-radiator sides like the tremendous ‘Capsicum’ by Stargo. It’s so euro, makes little sense, repetitive and cheesy to some ears, but I immediately got the warm, melancholic, shoddily produced yet joyous connection Neil had spoken of. I know little about Stargo other than they did a version of ‘Live Is Life’ (which is less good) and a track called ‘Superman’ that I could only stomach once, but I think I played ‘Capsicum’ more than any other record for the rest of the year, and drove my other half mad with that and ‘Spacer Woman’. It’s weird how you sometimes don’t really pay attention to things, and by twist of fate end up discovering some of the greatest records of all time by accident, and find yourself going through bins in second hand record shops across Europe like a wonky eurodisco J R Hartley looking for the next ‘Capsicum’. I don’t really care if it’s deemed cool or not tbh.

Ian Wade

ZZ Top via Queens Of The Stone Age – ‘Precious and Grace’

Billy Gibbons from ZZ Top plays guest guitar on a few tracks of QOTSA’s 5th album Lullabies To Paralyse. But it wasn’t until a few years ago, when we splashed out and bought the first vinyl pressing, that I heard the cover ‘Precious and Grace’ sung by Mark Lanegan. It blew me away but I knew instinctively it wasn’t a QOTSA original, so I looked it up and that’s how I came to love ZZ Top and Tres Hombres.

Lara C. Cory

Joe Jackson via Tori Amos – ‘Real Men’

What was it about Tori Amos’ version of ‘Real Men’ that so captured my pubescent imagination? Something in the yearning piano chords, stop-start rhythms, the intimacy of her bare voice in my headphones. Maybe the frankness of her direct-to-camera delivery of "don’t call me a faggot, not unless you are a friend" on national TV. Maybe something in the themes – gender politics, queer identities, miscommunication – resonated, abstract concepts that I would soon experience myself. It was raw and unfettered, tucked away at the very end of her stylish, avant-pop covers set Strange Little Girls. The entire album is a masterstroke, but only ‘Real Men’ drove me to investigate the original. Amos’ version is so perfect that I almost didn’t want to spoil it – but from here, I became acquainted with Joe Jackson’s angular New Wave in Look Sharp! but more particularly the sleek beauty of Night & Day, an offbeat Gershwin for the early Eighties. Jackson’s original is baroque New Wave-doo wop with a Spectoresque twist, strident and snarling where Amos’ version aches with sorrow. Usually the first version I hear of a song remains my favourite, but both of these have my heart; they show the emotional, brutal, triumphant power of interpretation.

Matthew Barton

Tim Hardin via Kula Shaker – ‘Red Balloon (Vishnu’s Eyes)’

I can’t bring myself to defend a penchant for Kula Shaker during their early heyday, even if I was barely into my teens at the time. What I do stand by, however, is a belief that their b-sides and the occasional album track were vastly superior to their procession of somewhat annoying singles. Their version of Tim Hardin’s ‘Red Balloon’ appeared as a b-side to ‘Tattva’ in 1996, Crispin Mills and band adding, naturally, a sitar, Hammond organ, a Garcia-aping guitar solo and some extra lyrics –something about Vishnu’s eyes. Clearly, the track was on a different level of songwriting to the likes of ‘Tattva’ and ‘Hey Dude’, and it therefore led me to the 1967 Hardin album it appeared on, Tim Hardin 2 (its first release came with Bobby Darin’s recording in 1966), with its other essential Hardin songs, ‘If I Were A Carpenter’ and ‘Black Sheep Boy’. That led to the rest of Hardin’s mercurial output, with its slightly aloof, world-weary, passionately literary, romanticism.

Barnaby Smith

Black Flag via Dirty Projectors – ‘Rise Above’

I was 16, it was 2007, and I asked a friend of mine if they’d listened to ‘Rise Above’ yet. I was feeling pretty smug about being into Dirty Projectors, and loved how the band wore their American Apparel hoodies zipped all the way up. Then my friend asked: “Do you know what that record’s a cover of, Suzie?” I can’t remember if I tried to pretend that I already knew who Black Flag were. What I do remember, however, is that same friend suddenly raising his fist above his head and, with a punch per syllable, shouting "SPRAY PAINT THE WALLS" at the top of his voice. He then gave me a three-minute lesson on Black Flag, drawing lines from Rollins and co to the screamo, post-hardcore and emo that I’d been ravenously consuming a few years beforehand (the heady, Myspace days of 2004/5). I then listened to Damaged around 300 times.

Suzie McCracken

The 13th Floor Elevators via Spaceman 3 – ‘Rollercoaster’

Over half of Spacemen 3’s debut album, Sound of Confusion, is made up of cover versions. Indeed, Side 2 is pretty much a tribute to The Stooges, but it’s to Side 1 that we must turn, for it’s there that we find their reading of 13th Floor Elevators’ ‘Rollercoaster’, a huge, monolithic wall of sound that celebrates Albert Hofmann’s inadvertent creation. Swirling, droning and aimed squarely for those navigating the uncharted recesses of their psyche, this was the soundtrack for 80s jokers, smokers and midnight tokers.

Quite how the leap from cover to source material was made has, unsurprisingly, faded into the mists of time, but the lightbulb moment of finally encountering the original sometime in the early 90s is flashback vivid. Unlike the slow pace of Spacemen 3’s cover, the 13th Floor Elevators original is as utterly bonkers as the experience it was paying tribute to, made all the more crazy by Roky Erickson’s yelping and demented vocals and a bizarre sound that gurgled throughout that later transpired to be Tommy Hall blowing into an amplified jug of water. Contextualising a little piece of musical history, it also served to notify just how fried that first generation of psychedelic explorers really was and how high those standards had been set.

Julian Marszalek

The Flaming Lips via Drugstore – ‘She Don’t Use Jelly’

In 1994/5, The Flaming Lips were already a bigger band than, as it proved, Drugstore would ever be. But not in my world. In my world Isabel Monteiro’s multinational, London-based indie trio were among the principal musical joys. I loved Monteiro’s quixotic writing, her sharp-toothed variations on the quiet-loud-quiet-loud post-Pixies formula, as well as her onstage charisma and the band’s compressed energy, which never fully transferred themselves to record. I saw them live every chance I got; they were invariably great, and the audience always went doolally for a weird, charming, strung-out little song with a kicking chorus. I assumed it was one of Monteiro’s (she was certainly capable of it); somehow I’d managed to miss that ‘She Don’t Use Jelly’ had been a breakthrough US alternative hit barely a year before for its originators. I’ve spent my share of time with The Flaming Lips’ music since. For all that I relish it, I wouldn’t trade any of it for those memories of Drugstore making ‘Jelly’ crackle with life and delight.

David Bennun

The Sonics via The Cramps – ‘Strychnine’

When it comes to songs as gateway drugs, then the biggest dealers were psychobilly godheads The Cramps. And not only that – they held only the good stuff. Their mission wasn’t so much to present their judiciously selected covers as something new as to maintain a tradition of deviancy that stretched back decades. This was a manifesto of sexual fetishes, social delinquency and the joys of mind-altering substances.

Crucially, reading the non-Rorschach/Interior credits on the label of Songs The Lord Taught Us suggested that there were others out there just like them. And that they happened to stretch way back to a time before decimalisation and your own birth simply added succor to this disciple of fetishes, delinquency and mind-altering substances. And it’s lasted well into adulthood, too, along with a love of red-raw garage rock’n’roll from the Pacific north-west that still resonates to this every day.

Julian Marszalek

The Carpenters via Sonic Youth – ‘Superstar’

It was the cover that got me first: a cartoonish girl and boy on a garishly-coloured cassingle. I’d buy so much of my music on image back then, 29p oddities scavenged from bargain bins, hoping the music might match. Sonic Youth’s cover of Superstar was the opposite of that image. It was a smoky, dark murmur whirling in from a wax cylinder, from “long ago and oh so far away”. It nailed the heavy longing that can come when you’re young, or when you’re a fan, and it drew me back to the Carpenters’ glossy original.

I’d thought of Karen and Richard as bouncy characters before, but I found that heavy feeling of Superstar was still there. Karen’s voice gave the song a misplaced glow of hopefulness, and an even sadder finale (never have the words “I love you, I really do” sounded so melancholy, so innocent, so softly desperate). I burrowed into the Carpenters’ back catalogue after that, finding even more depth of feeling. Sonic Youth always knew it existed. I’ll always thank them for drawing me towards it.

Jude Rogers

Mission Of Burma via Graham Coxon – ‘That’s When I Reach For My Revolver / Fame and Fortune’

When Graham Coxon released his second solo album, the criminally unsung The Golden D in 2000, the words “Mission of Burma” meant zip to me. Though I was up on, and down with, how his affinity for American guitar music coloured the more inspired, scuzzed-out peaks on Blur LPs Blur and 13, I hadn’t bargained for how well that manifest itself on his own terms. Snapped up on a whim, The Golden D crested, for me, on two fist-clenched and remarkably faithful covers of ‘Fame and Fortune’ and ‘That’s When I Reach For My Revolver’ by the aforementioned Boston post-punk heroes. Featuring Coxon on all instruments, combined, they served as a perfect portal to Mission of Burma, their stellar Signals, Calls, and Marches EP and beyond (that is, after an embarrassingly long time assuming they were Coxon originals.)

Brian Coney

The Kinks via The Cardiacs – ‘Susannah’s Still Alive’

Arriving a year after their infamous 1987 Tube appearance, Cardiacs’ fourth single, Susannah’s Still Alive, was the only cover version ever recorded by the band. Originally released as a single in 1967, and credited solely to Dave Davis, with the Kinks as his backing group, Cardiacs retained the song’s essential sense of English eccentricity, whilst ratcheting up both tempo and weirdness quotient to a suitably manic degree. Recorded in a day at the Slaughterhouse Studios in Driffield and featuring also on the Kinks’ tribute album, Shangri-La: A Tribute To The Kinks, Tim Smith’s overall arrangement and Bill Drake’s harpsichord additions truly made the song their own. It also features one of Smith’s best guitar solos at the 1:45 point, combining ecstatically wrought sustained notes with backwards and sped-up passages. Perhaps only equalled by Smith in his ‘R.E.S’ solo, Davis’s version sounded too slow and its harmonica passage no fair substitute for the psychedelic pop pyrotechnics of Smith’s guitar when I first heard it. With some further digging I realised the close affinity between the two bands’ very English take on idiosyncratic pop music, best typified for me in the Kinks’ masterpiece, The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society.

Steve Payne, who directed the video, said: “I liked the original song but the Cardiacs version is better, it just has a weird energy to it. The camera was on a cable – an old pneumatic recorder with a channel on one end and the recording device about 12 foot away. We were playing the music on a tape, so it would be at constant speed, and I just filmed whatever they did. I had a pretty clear idea of how I wanted it to look, sort of claustrophobic, and it was just magical.”

Sean Kitching

The Pop Group via Loop – ‘Thief Of Fire’

While Loop may have had the gnarled kosmischebiker grunginess down pat, with their burning eye logo and wind-tunnel rockout noise to guide them to places other late Eighties bands could never quite reach with such speedball conviction, the inclusion of ‘Thief Of Fire’ on the b-side of ‘Collision’ was an actual revelation.

That ranting scrawl of reverbed ire that Robert Hampson brought to Loop’s cover was nothing in comparison to encountering the scathing snarl of Mark Stewart on a mint copy of The Pop Group’s original, courtesy of Reckless Records’ voluminous second-hand shelves. Where Loop were acid-scraping the troposphere, The Pop Group were mining seams of disjointed dub, funk and free jazz on Y that few had hitherto considered. This was where the system was actually being smashed, it seemed. Here was the onward link to Stewart’s majestic dubwise post-industrial versioning of “Jerusalem” for the new dark ages; and there was much more righteous virulence to come.

Richard Fontenoy

Big Star via Elliott Smith – ‘Thirteen’

Some things just bear spelling out: Elliott Smith genuflected hard at the altar of pop music. From The Kinks and the Beatles to Cat Stevens, the Zombies and far beyond, his live shows were often strewn with myriad FM-friendly covers. Over the years, a supremely skeletal take on the heart-strung ‘Thirteen’ by Big Star has emerged as a textbook case in point and, for fans such as myself, a gateway to the Memphis power-pop masters in question. Co-written by Alex Chilton and Chris Bell, its gently lapping folk-pop ache assumes a whole new air of muted solemnity in the capable hands of Smith. While the studio version that features on the 2007 comp New Moon is easily the best, I’ll forever be in debt to a ropy bootleg version that steered me in the direction of #1 Record way back when.

Brian Coney

Mickey Newbury via Joan Baez and John Denver – Various Songs

The late Mickey Newbury is perhaps the most underappreciated artist I know. Even Americana aficionados are often unfamiliar with his name, and unaware of his baroque, psych-tinged, deeply melancholic country-pop and masterly songwriting. Unlike such late Sixties and early Seventies peers as Jimmy Webb and Kris Kristofferson, he never had a major star of the moment turn a song of his into a canonical classic; the nearest he came was Kenny Rogers and First Edition’s tremendous hit version of ‘Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)’, and Elvis Presley adopting his arrangement of traditional tunes, ‘An American Trilogy’. I first became aware of him through Joan Baez’s 1971 Blessed Are album, much played in my childhood household, when I became fascinated with the tragic, gorgeous, bewildering ballad, ‘San Francisco Mabel Joy’. I heard it again on John Denver’s rather tepid 1981 Some Days Are Diamonds, and even that couldn’t diminish its mystery. With typical contrariness, Newbury recorded a 1971 concept album, Frisco Mabel Joy, which didn’t include what was then his best-known song – the source of further puzzlement when I eventually tracked it down. But I did discover what a sublime talent Newbury possessed.

David Bennun

The Velvet Underground via R.E.M – Various Songs

By the time R.E.M. completed their journey from art college rockers to global superstars with the release of ‘Losing My Religion’ in 1991, they had left a ten-year trail of breadcrumbs into previously hidden musical universes for eager new recruits to follow. A choose your own adventure that could lead to Patti Smith – via Michael Stipe’s oft-told tale of listening to Horses LP while eating enough cherries to make him puke, to Robyn Hitchcock, 10,000 Maniacs or Vic Chestnut through their collaborations, or to Television’s </>Marquee Moon, thanks to 1988 fanclub-only release ‘See No Evil’. After falling hard for </>Out Of Time, a six-month spree sourcing R.E.M. LPs followed. Among the IRS label early-career masterpieces was </>Dead Letter Office – a goofy collection of B-sides and rarities released in 1987, featuring cover versions and late-night studio shenanigans featuring THREE songs by The Velvet Underground. Talk about wearing your influences on your record sleeve. ‘There She Goes Again’ (released as B-side to debut IRS single ‘Radio Free Europe’), ‘Pale Blue Eyes’ (included as bonus track on 12” of early single ‘So. Central Rain’), and ‘Femme Fatale’ (bonus track on 1986 single ‘Superman’, itself a cover of The Clique) were faithfully, earnestly and lovingly reproduced – albeit sounding more wholesome than the original versions. Lou Reed, apparently, approved. Imagine that. Oh, and the B-side of ‘Losing My Religion’? A live version of ‘After Hours’ by The Velvet Underground…

Adrian Lobb

La Düsseldorf and Neu! via Stereolab – Various Songs

Stereolab never made their introductions to the joys of Neu! and La Düsseldorf by means of direct covers. Instead, their influence was tangential, their gateway wide and welcoming at a time when recently forgotten non-mainstream music was often hard to find beyond short-run fanzine references and obscure LP liner notes. The now seemingly omnipresent motorik form that Michael Rother and Klaus Dinger had driven metronomically into the pre-punk Seventies had been largely forgotten until Stereolab brought it – as well as the much-derided lounge pop groove and the semi-ironic bah-bah-bah vocal – to an enthusiastic revival two decades later.

Ironically, it took Steve Stapleton of Nurse With Wound remixing the ‘Lab into ‘A Wonderful Wooden Reason’ to bring things full circle(ish) by remaking them into the image of Faust’s ‘It’s A Rainy Day’ in turn. Stereolab had helped reboot a pan-European underground energy, the Anglo-French lyrics as melodically political as Neu!’s were minimal and La Düsseldorf’s were both proudly local and globally out there.

Richard Fontenoy

Aerosmith via Run DMC – ‘Walk This Way’

I was 13 when Run DMC’s ‘Walk This Way’ came out and for many people my age it was the musical event of the summer. We instinctively knew there was something special about it even if most of us weren’t aware it was a cover (or that it was the start of a fusion genre that would spawn some of the best and the very worst records of the next 15 years). One assumed the hilarious Mick Jagger-alike in the video was a dupe, a beautifully-realised caricature of a petulant vocalist. Imagine our surprise when we opened Smash Hits and the rockers in the video turned out to be a real band. I was certainly not alone in discovering Aerosmith via Run DMC – there are literally millions of us who sought out this weird Boston glam metal band and fell in love with them thanks to the New York hip hop trio. Pocket money spent on Aerosmith’s Greatest Hits revealed ‘Dream On’ – one of the greatest baroque pop ballads ever written. Their version of ‘Walk This Way’ is pigshit however.

Jeremy Allen

Nina Simone via David Bowie – ‘Wild Is The Wind’

Bowie is for my money the greatest pop star who ever lived. But still, it’s a little known fact that 98% of his versions of other people’s songs aren’t very good. Look at covers album Pins Ups, his worst LP by far, and then compare it to the record which he stole the idea from – Bryan Ferry’s These Foolish Things. Ferry’s croony matinee idol schtick makes him almost constitutionally obliged to breathe new life into old standards, whereas Bowie is better when he’s cross-breeding arcane ideas and inventing something new with them. Credit where credit’s due, his version of ‘Wild Is The Wind’ is sweeping, wistful and majestic, but if I had to choose a version it’d be the one by Nina Simone that he took inspiration from. Simone’s – a cover itself, of Johnny Mathis – is of an emotional heft and poignant beauty that’s hard to locate other than on further Nina Simone records (which I duly sought out after this one).

Jeremy Allen